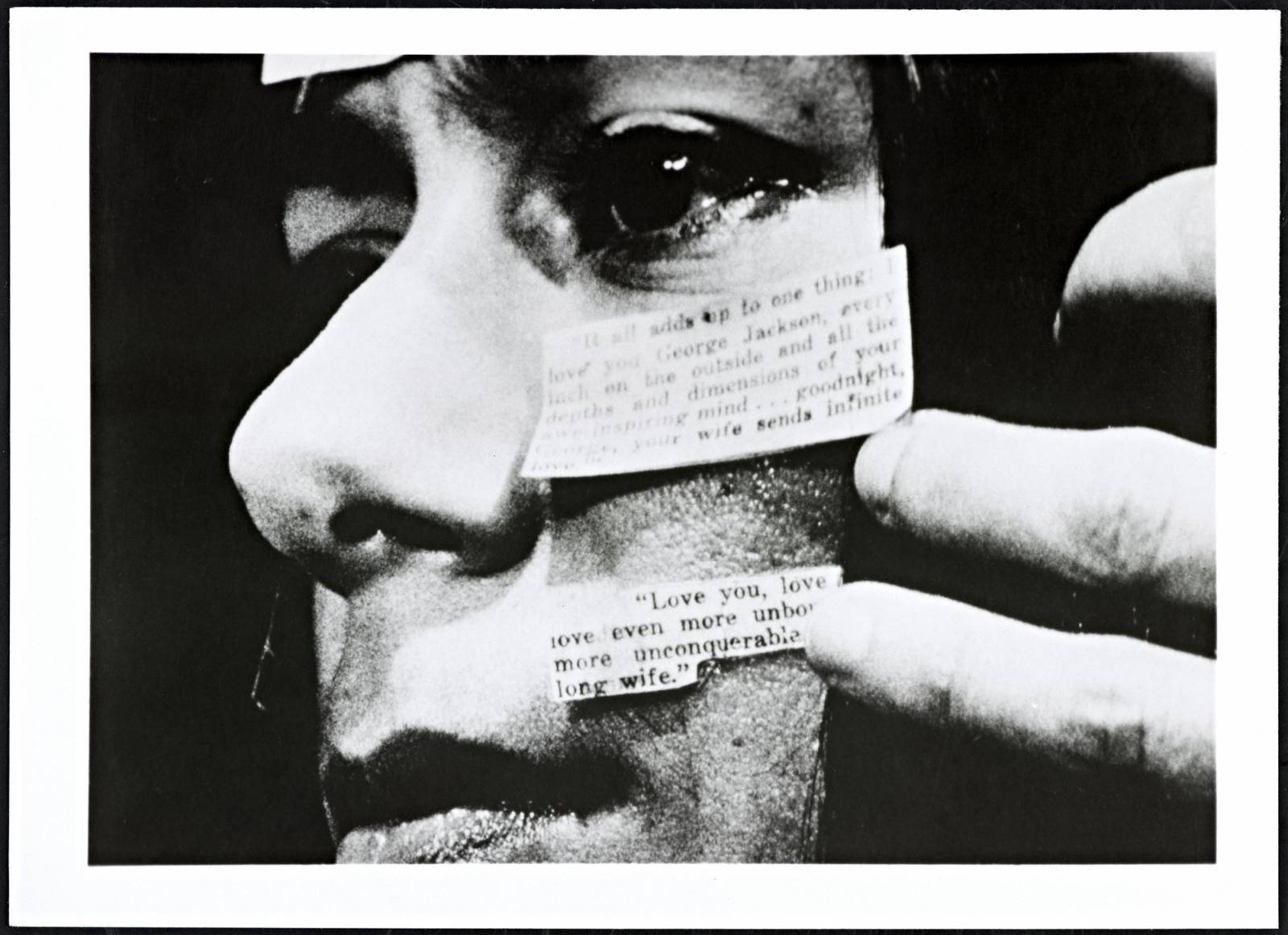

Ishmael Houston-Jones is an improvisational and often collaborative choreographer, curator, and teacher. Currently he is curator of DraftWork, an afternoon series of works-in-progress at Danspace Project in New York, and teaches at New York University and University of the Arts in Philadelphia. In 1982 he curated “Parallels” at Danspace, asking, “What is post–Alvin Ailey Black Dance?” Thirty years later, with Platform 2012: “Parallels,” he offered an updated reflection on the relation between dance makers of the African diaspora and postmodern choreography. After a decade-long hiatus from choreographing, during which he performed in the work of Miguel Gutierrez, Yvonne Meier, Lionel Popkin, and others, in 2010 Houston-Jones restaged THEM, a 1985 collaboration with writer Dennis Cooper and composer Chris Cochrane, which explored aggression and sexuality and had premiered during the AIDS epidemic. In his curatorial work Houston-Jones has also looked back, with, most recently, “Lost and Found” at Danspace, focusing on the generation of artists lost to AIDS and the legacy of that loss.

IToP

With what kinds of artists or art professionals are you most comfortable conversing? Who speaks your language? Those in the visual arts, those in the performing arts? Sculptors, filmmakers, set designers, composers, playwrights, fabricators, actors, critics, curators, producers? Conversely, whose language is most unfamiliar to you?

IHJ

For me, “who speaks my language” is more a matter of the individual than of the profession. There is not one type of artist (or person in general) with whom I feel more or less comfortable conversing about my work. If pressed to make a huge generalization, I would say that artists can be more familiar with the peculiarities of the language that I use, but that definitely does not always translate into a clearer understanding than talking with a “lay” person. Perhaps I do enjoy talking ideas with designers (lighting, sound, set) more than with producers or critics, or even fellow choreographers, but this is definitely not always the case. I have had very fruitful conversations with composers, filmmakers, designers, and curators, and I have had frustrating encounters with the same. I would say that I am always curious about points of view that are different from mine. I am stimulated when others are curious about my work and process. But, again, these interactions do not break down along disciplinary lines for me.

IToP

What does it mean for an artist to be “literate” in the disciplines he/she engages? Is an awareness of the history of practice in those mediums necessary or desirable? What are the possible benefits of being “illiterate” within certain disciplines?

IHJ

An awareness of the history of the discipline is usually beneficial. I think it is important that artists, young artists in particular, realize that works of a particular type (e.g., site-specific performances, or work that appropriates rituals of another culture) have happened before. But also that every work is created in a particular cultural context. Artists should be aware of the history and context of an art form without letting that knowledge stifle their own creativity.

IToP

It seems that Danspace’s programming responds to the need for this awareness by creating a kind of channel back into the history while maintaining a resonance in the present. Bringing old works up to date by restaging them and illuminating both moments. How do you see the role of your curatorial work there?

IHJ

I have two curatorial roles at Danspace Project. I am on staff as the DraftWork curator, and I have been a guest artist curator for two multi-week platforms.

The DraftWork series presents work in any phase of development—from the germs of an idea to work that is almost ready to be performed. Although I choose the two choreographers for each program then lead a discussion with the artists and the audience, I feel that “curator” is not exactly what I do with DraftWork. I am more of a programmer and scheduler. Sometimes there are happy accidents when the work of two artists has commonalities, but the program is dictated more by which artists are available on which Saturday afternoon and by which Saturday afternoon Saint Mark’s Church is available.

Curating Platforms involves much more attention to the details and peculiarities of what will take place. In addition to performances, there are panel discussions, film screenings, workshops, and a printed catalogue, all focused on a specific topic. These topics can vary, from the work of a single artist (Susan Rethorst, DD Dorvillier) to a certain period in dance history (“Judson Now”), or they may be more thematic. The two for which I have served as curator are Platform 2012: “Parallels” and Platform 2016: “Lost & Found.” Both of these were prompted by very specific questions. “Parallels” asked: What is post–Alvin Ailey Black Dance, and is there a mainstream of Black Dance that choreographers are pushing against? And if there are, who are they? “Lost & Found” interrogates how the deaths of so many young and mid-career dance artists from AIDS has affected dance making today.

“Parallels” was eight weeks of dance activities looking at the work of “post-Ailey” choreographers from different parts of the African diaspora. There was a wide range of work performed, from more traditional postmodern (Kyle Abraham, Dean Moss) to work that was more conceptual or cross-boundary (Nora Chipaumire, Okwui Okpokwasili, Stacy Spence, Will Rawls, and works from the Internet). I also screened works from the original “Parallels” series that I curated in 1982, and I oversaw panels and a 100-page catalogue.

As I write this, the opening of “Lost & Found” is three months away, and co-curator Will Rawls and I are finishing details of the six-week platform. He and I chose all the artists and curated the activities. The opening weekend will feature screenings of archival work by Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, Neil Greenberg, and Willi Ninja. Will and I will also conduct public discussions with Jones, Greenberg, and Archie Burnett (representing the vogueing and house communities). We will screen a film by Charles Atlas, present a reimagining of work by John Bernd, who died of AIDS complications in 1988, and offer work by emerging queer choreographers and performance artists as well as special memorial events, public conversations on the topic, and of course a printed catalogue.

IToP

Your work as a curator helps establish a vocabulary of reference points for young artists today. Do you see your choreographic work and your curating dovetail together in a certain way?

IHJ

I think that I curate in much the same way that I choreograph. Almost all of my choreography is improvised, and I use that same sense of intuition when I curate. That is, I am excited by what it is that I don’t know, and seeing what happens when “A” is placed before “F” and after “Q” rather than a logical “A, B, C.” I like proposing that meaning can be derived from seeming chaos.

IToP

Can you describe for us a time when your work either suffered or benefited from a miscommunication, when the assumption of one’s intent was misconstrued as a result of moving from one artistic context to another (i.e., visual art vs. theater or music)?

IHJ

The most serious breach in communicating about my work and its intent occurred between a European presenter and me. This person’s image of what my work signified as the creation of an African American artist and how it would translate in a European context was very different from how I envision my work. There were huge assumptions about my process and practice and the representation of the Black body that damaged the integrity of the work that was being commissioned. This work, The Onyx Table, a collaboration with Fred Holland, was commissioned by the Klapstuk Festival in Belgium in 1987 and has never been presented in the US.

IToP

Would you mind describing what the assumptions were? Was the work presented, in the end, and how was it received? Could you see what happened with The Onyx Table happening in 2016?

IHJ

That example was an anomaly. I am not sure exactly what was expected, perhaps something more “primal” or “primitive” or “ethnic.” The producer was never clear about his displeasure. In the end, I felt that The Onyx Table wasn’t Black enough in the producer’s view. Also, Fred and I did not appear in the work. We went on to perform it in several venues in the Netherlands. Because of the commissioning producer’s aversion to the work, it carried a certain amount of public baggage. I think we got what could be considered one positive review and a few mixed ones. It has never been presented since. I think this situation can and does occur whenever the ego of a presenter is too large to allow artists to have their own voice.

IToP

How has the language of performance—specifically the words used to describe it—changed during the time you’ve been an artist? What words do you find most resonant in a contemporary art and performance world? Have changes in vocabulary impacted the way you describe your own work? Which words most confuse or annoy you, and which have stayed with you?

IHJ

An example of this for me is the use of the word curate and the phrase curatorial practice, which resonate with me since part of my self-definition is a dance curator. The term curator was borrowed from the visual arts. It denotes one who selects and cares for a collection of works to conform to a certain proposition, either the concept for an exhibition or the cultural identity of a museum department, and puts that work into context for the public through exhibition/performance, public discourse, cataloguing, etc. As I mentioned, my role with DraftWork is more of a programmer/scheduler, while what I do with the Platforms at Danspace is truer to the sense of the word curator. At times I feel that when the word is used in a dance/performance context, it is because it has a more highfalutin’ sound than presenter or programmer.

The other shift in language that I’ve noticed is the use of words taken from semiotics and critical theory, such as signifier. Also the terms process and practice are used in a more particular way to describe art making. When used correctly these words can clarify intent or specific actions; when used haphazardly they add confusion.

IToP

Were there issues of literacy or illiteracy when you have worked with collaborators across disciplines, such as with artist Nayland Blake (Hare Follies, 1997) or writer Dennis Cooper (THEM, 1985)? For example, the words you used to describe certain aesthetic or procedural goals, different expectations for the function or effect of spoken text, etc.?

IHJ

The making of Hare Follies and THEM were two very different processes. In Hare Follies Nayland Blake was definitely the director of the project. He gave me a script outline and told me what his ideas were for each section. I gave him my responses to his prompts, and we had a variety of discussions, but the ultimate decisions were always his. It was clear that it was his piece, his vision. It is not the way I usually work, but it was not bad being directed in someone else’s process. I didn’t feel that I had less agency. In the social contract we made, we had defined roles. He was directing his piece and I was choreographing for his piece. It was actually quite clear and in that situation straightforward. I like participating in other artists’ pieces, but it works best when the roles are well-defined.

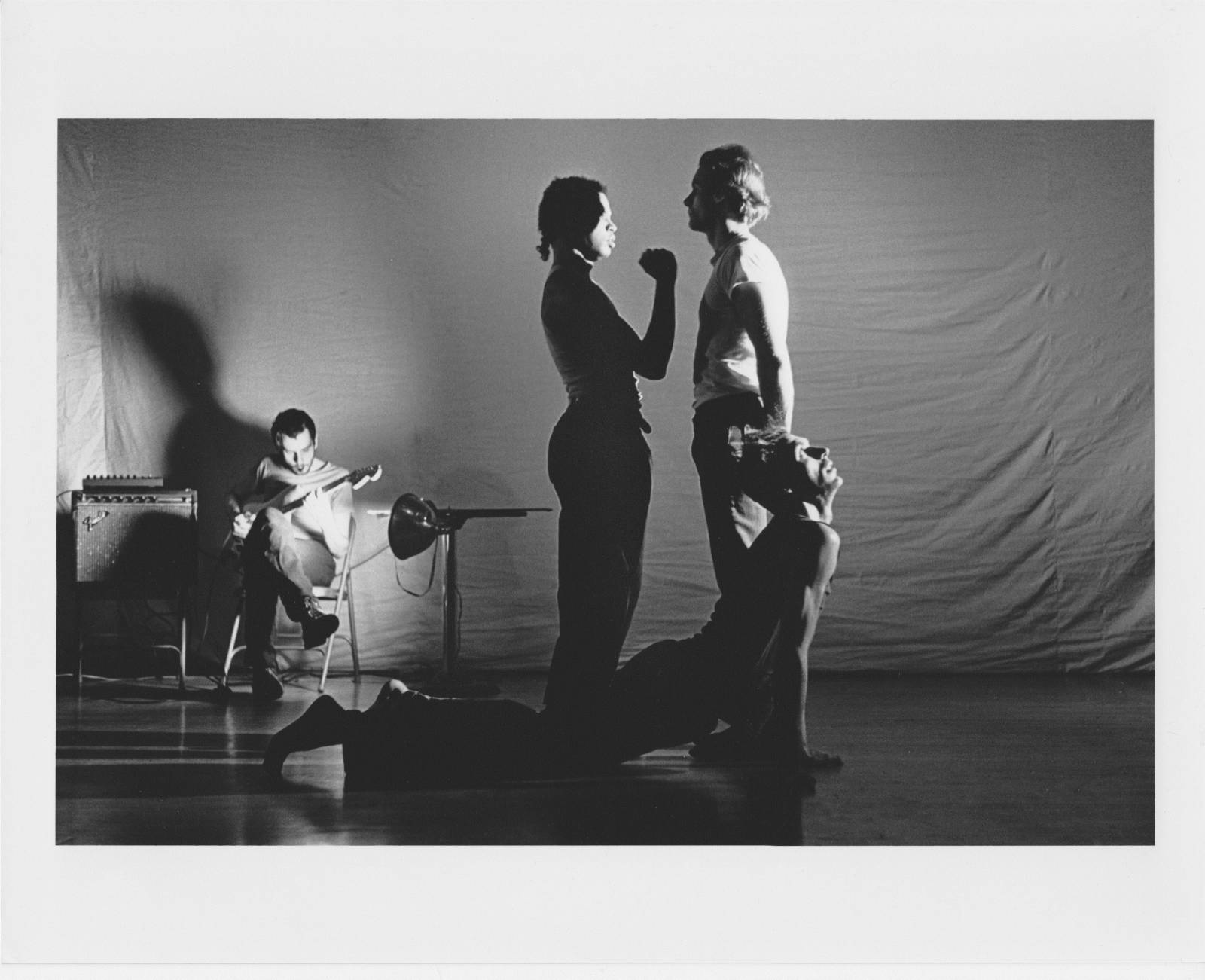

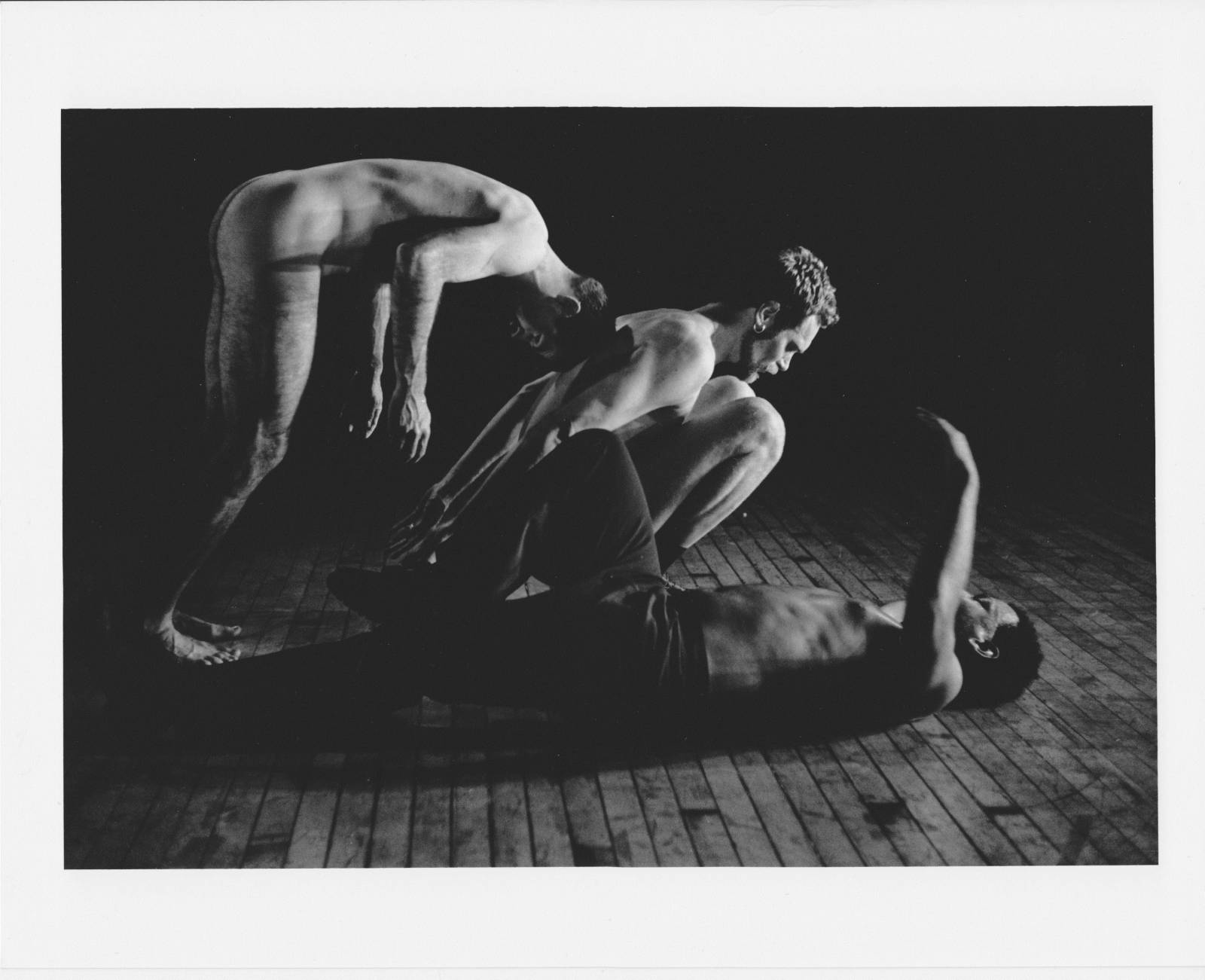

THEM was made very differently. Writer Dennis Cooper, composer Chris Cochrane, and I were always in the room together for all the creation rehearsals. The piece was developed along three independent yet intersecting tracks—text, music, dance—and each track had equal weight. The three of us would organically shift who was leading discrete sections in rehearsal. Sometimes Chris would come in with music samples; sometimes Dennis would have written something that Chris and I would respond to; or I would have a movement idea and would see if it sparked anything in the other two. I could also suggest text or music ideas or edits and the others would give feedback on the dance. The dancers in the original production also contributed a lot. None of the choreography is set, so each performer contributes much to the final piece. I definitely structured the dance improvisations either spatially or emotionally. It is hard to recall specifics of the language we used because the process was so organic and easy between us all. I think we talked in terms of tone and color or perhaps mood and atmosphere. But it was one of the easiest collaborations in which I’ve participated.

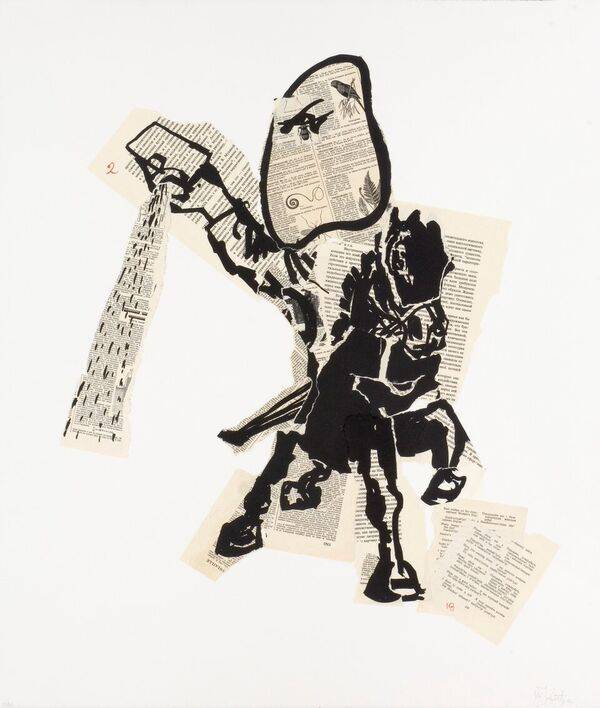

Also easy, but different, was Cowboys, Dreams and Ladders (1984), made in collaboration with Fred Holland, who was both co-choreographer and visual designer. That piece started with a conversation Fred and I had about a documentary he’d seen about an all-Black rodeo in Oklahoma that led to him and me researching the roles of Black cowboys in the reality and the myth of the settling of the American West. Since Fred and I had been friends for several years, a lot of our process was the conversations we had about the images we were creating as Black male bodies dancing on the postmodern stage, using the invisibility of the Black cowboy as metaphor. We were equal partners in creating the dance sequences, but Fred took the lead in the visual design, with some input from me. Again, the language was that of friends kibitzing, often in bars, about what could happen in the piece.

IToP

In these and/or your many other collaborations, were there ways in which you discovered that you were able to show each other elements of your disciplines in a different light, or see the opportunity to play with or subvert disciplinary conventions that you might otherwise take for granted?

IHJ

I think that I have an instinct for choosing collaborators who will challenge me but will also be compatible partners. I also usually know when to turn down projects that I feel will not work. There are some red flags. The clearest one is a muddy concept of roles that a creative team are to perform, e.g., who is the director, who will be the final authority on what the piece will ultimately be. Confusion about money can also be a red flag. And even if the project is exploratory, there should be some overarching idea about what going to be explored. In the pieces I’ve cited above, I feel that there was a natural stretching of boundaries for all concerned. Before Hare Follies I don’t believe that Nayland Blake had attempted making a full-length performance work in a theatrical setting and I had never been the choreographer for a project that someone else was directing. In THEM I had never relied so heavily and entirely on words written by someone other than myself; Dennis Cooper had never written for a dance performance; and while Chris Cochrane is a brilliant improviser, he had never scored a full-length dance piece before. We were all treading in new territory. Fred Holland and I had done many short improvisational pieces together, but Cowboys, Dreams and Ladders was our second evening-length piece; Babble: first impressions of the white man (1983) was our first. I think Babble taught us a lot about our different approaches; Fred is more visual and I am more kinesthetic in our image making. In Cowboys, we refined the language we used to communicate our ideas.

IToP

In your feeling free to collaborate across disciplines, you are presumably not seeking to develop or refresh some element within the bounds of a discipline in the way that, say, a musician might work to isolate sound from melody, or a playwright to create character without narrative. What is it that you are seeing in common with a new collaborator with whom you are proposing to work? Maybe admiration or friendship comes first, but is there also always or necessarily an affinity of aesthetics, politics, sensibility, etc.?

IHJ

Not to be glib, but “all of the above” applies. Sometimes one thing more than another. For example, the dominant attribute can be admiration of the potential collaborator as an artist in her or his own right. I asked Dennis Cooper if he’d consider writing for me after hearing him read just one time. Sometimes it is a political or aesthetic affinity, or even an opposition. Fred Holland I were friends, but we were also aware that we were Black male artists in a largely White downtown postmodern dance scene.

IToP

How would you describe the relation between improvisation and interdisciplinarity? Does improvisation offer a way past some of the structures that tend to define disciplines, such as narrative or character in theater, and in turn allow a critical look at them as the conventions that they are?

IHJ

I’m not sure I understand the question. In dance, improvisation is always structured to varying degrees and may lend itself to both narrative and character as well as abstraction. In performance, improvised choreography and set choreography are only different with regard to their relationship to temporality—improvised choreography is created in the moment in front of an audience, and set choreography is made to be repeated as nearly as possible the same way each time it is performed. Both improvised and set choreography share the same compositional concerns of moving human bodies through space and time. Therefore, they have more or less the same relationship to narrative and character. But since I think most, if not all, set choreography begins with degrees of improvisational sketching, in this phase of creation improvisation might be more conducive to working through ideas with other disciplines. But interdisciplinarity could just as well happen if, for example, completed or nearly completed set choreography were given to a composer, or conversely if a set text were given to a choreographer. There are always knowns and unknowns in the creative process; there are only differences of degree.

IToP

At what point do we start looking at an artistic work in a way that goes beyond its disciplinary designation, i.e., “dance” or “theater,” and see it as simply performance? Do you differentiate between dance and performance art in your own thinking?

IHJ

I don’t think interdisciplinarity is a twenty-first-century western invention. Nineteenth-century European opera, Kabuki, Bharatanatyam, and even Broadway musical theater are all examples of interdisciplinarity. In the west there are generally expectations associated with going to a “dance” performance as opposed to a “theater” one. And there is the hybrid known as “dance-theater.” Each may provoke particular anticipations. Then there is “performance art,” which is slipperier. The performance art created by dancers is usually different from the performance art made by visual artists. I have found that the authorship (Robert Wilson, Eiko Otake, DANCENOISE) or venue (Bill T. Jones at New York Live Arts, Bill T. Jones on Broadway) of a work often determines the lens through which I will view that work. But in the end my critique of work rarely depends upon its discipline.

IToP

How have you observed the interdisciplinary impulse evolving and maturing since you started out in the theater and dance world? How have the boundaries between dance and theater changed or shifted?

IHJ

I feel that the shift has occurred primarily in that certain work is now labled interdisciplinary where, as I implied above, everything from The Mahabharata to West Side Story are actually examples of interdisciplinarity. There is still work that is labeled dance and work that is labeled theater. Authorship, venue, and whether movement or text is foregrounded often determines these labels. The works that I would view as interdisciplinary are those in which movement and words are more equal in importance to the content of the work or if the actual location of the performance is in a “nontraditional” venue—beach, rooftop, moving vehicle, etc. Also if the author is known as working in a genre other than the one that is being presented, that might lead me to think of the work as interdisciplinary. My own work most often begins with a kinesthetic impulse, but it will often involve much text, music, and visuals; I am never concerned if it is viewed as dance or as something else, usually theater or performance art.

IToP

Has the mainstreaming of interdisciplinarity, i.e., a more general acceptance and interest in its practice, paralleled a kind of analogous opening up to a broader range of influences, cultures, and traditions in dance and theater, in a parallel kind of defiance of expectations? If so, do you see those developments as related?

IHJ

I believe that in mainstream culture there is a greater acceptance of work that is more challenging and more resistant to being pigeonholed. Whether it’s dance/films created for the Internet, audience immersive environmental theater, or dance performed in the galleries of major art museums, there seems to be more willingness to accept pieces on their own terms and to not be so concerned with how work is labeled (and marketed). There are still traditionalists, often found among critics, who bristle when genre lines are crossed, but in the general art-going public, people are less concerned with what work is called than how it viscerally affects them.