William Kentridge (born 1955, Johannesburg, South Africa) is a graphic artist, filmmaker, and theater artist renowned for his humanist and poetic perspective on apartheid, colonialism, totalitarianism, and their lingering effects. Best known for his allegorical animations of charcoal drawings that he erases and appends frame by frame, Kentridge has explored disciplines ranging from sculpture to books, stereoscope to opera. His works are included in numerous international collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Tate Modern, London; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His acclaimed production of Lulu premiered in November 2015 at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

IToP

You are often referred to as an exemplary interdisciplinary artist. Does that term, “interdisciplinary,” have any specific meaning and value for you?

WK

No, the language used to describe artists is not of interest to me. What I’m interested in, what I celebrate, is the state we are in today, in which it is possible for an artist to say that his artwork for the day will be a poem, or a piece of music, or a performance, which would not have been the case some years ago. It would still be very difficult for a poet to say, The poetry that I’m writing today is in fact this drawing, or a choreographer to say, The choreography that I’m doing this week is a sculpture. But visual artists have gained a lot of freedom, which was won by the Dadaists, by Duchamp, by the people who expanded the boundaries of the arts.

So I think of myself as making drawings, but sometimes the drawings are conventional, two-dimensional drawings; sometimes they move through time with animation—that’s like a three-dimensional drawing. Sometimes they’re on a stage, in which you have depth as well as height and breadth and time, so that’s like drawing in four dimensions.

IToP

Does the ability to draw readily upon various disciplines better facilitate the delivery of content and ideas for you? Does it allow for greater play or freedom in the creation of your work? What do you hope for the audience to experience in such contexts?

WK

My experience with different materials and mediums in my work is that, very often, drawings emerge that are kind of like applied drawings, made in the service of a piece of theater or a film, and they are drawings that I would never have arrived at if I were simply making a drawing for its own sake. The medium that I’m working in makes narrative or theoretical demands that push the drawing in a direction it would not go in if I were only thinking about drawings and the history of drawings. So working across disciplines becomes a strategy for expanding a vocabulary, for finding different ways of surprising myself. The hope is that audiences are happy to go on this journey; it is a journey of the migration of images across mediums.

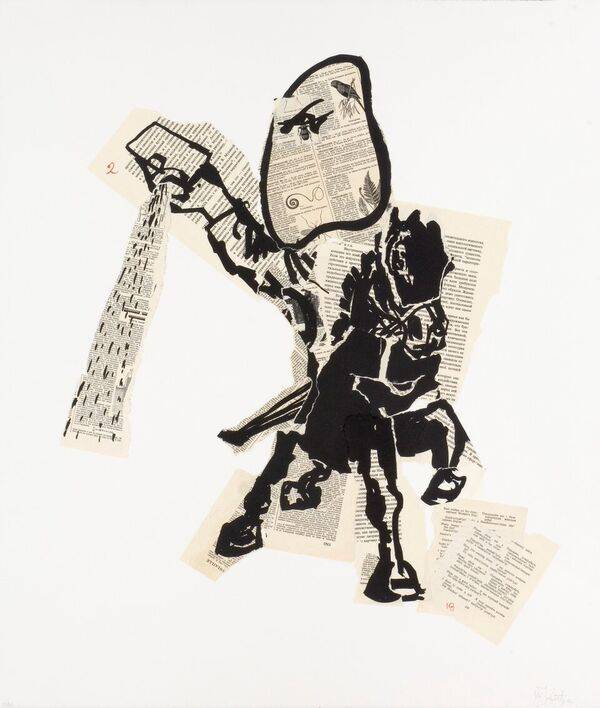

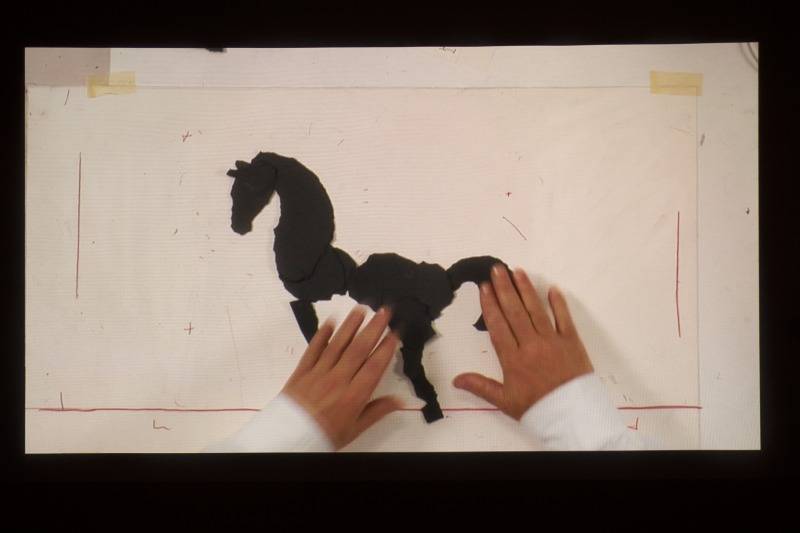

So a horse can be a tapestry, a sculpture, an etching, a performance on stage, a projection; it can move through these mediums, and each of the different forms it takes propels something. A torn paper horse made for an animation in turn makes a particular sculpture when it’s translated into wax and wood and cardboard. There are ways in which a collage shifts and changes when it gets turned, when the layers are meshed together on the loom of a tapestry. This instability of images is a very important thing for me.

IToP

You were trained as an actor before going to art school. However, your work has emerged within the context of the visual arts, although it engages performance consistently and in various ways. Did the visual arts offer a different framework with which to incorporate performance into your practice? Is performance related in some way to your drawings and other graphic work?

WK

In fact, I went to art school before I trained as an actor. I went to evening classes at the Johannesburg Art Foundation, and I even spent a year full-time there after I finished studying politics and history at university. Then I gave up art, having decided I’d failed as an artist, and only then did I go to theater school to try my hand at acting. I’d been acting all along as a student, but I thought I would do some training. I discovered after three weeks that I should not be an actor. But I learned a huge amount about directing and about drawing. I learned more about drawing from the theater school than I did from the art school. If I teach exercises to drawing students or animation students, they’re almost always the theater exercises we did at Ecole Jacques Lecoq.

It has to do with understanding the energy of a gesture, of what it is to use one’s whole body, of expanding the repertoire of degrees of tension with which one can work, whether one is speaking, moving, or drawing. It’s also a way of expanding from the body outward into finding a meaning in the work.

Obviously, the visual arts gave an important impulse to the theater work, in the sense that when you make a drawing, it’s not as if you start with a script or a storyboard. Trying to maintain that same openness when working in theater became a different way of thinking about theater; one didn’t know what the end result would be, but one had the six weeks of making, or the three months of making, in the same way one would have the three hours of making a drawing. What you are making is discovered in the act of making it, during that process. That’s why even when I’m working in theater, I think of it as a kind of drawing.

IToP

When is your work constrained, and when it is enabled, by traditional theatrical or film conventions?

WK

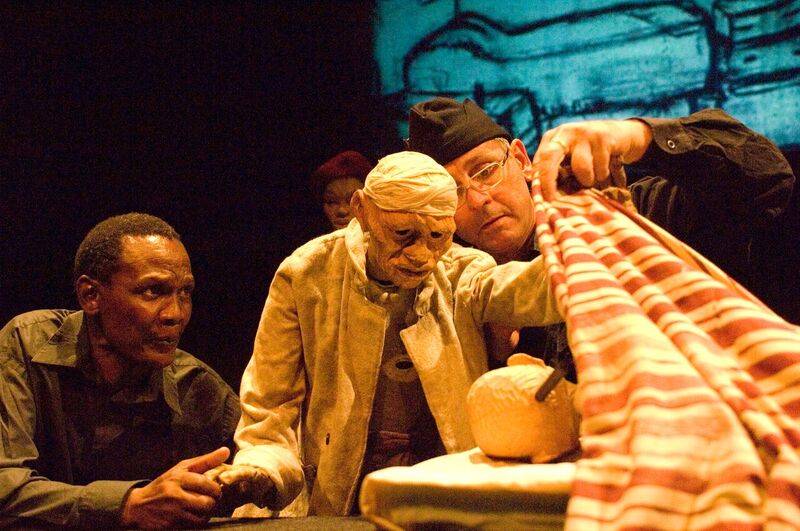

I am very interested in the history of the different mediums, looking at different historical ways of thinking about theater. Certainly, early cinema is a very important part of thinking about cinema. But very often there is value in a half-understood or partially understood history of a medium; I believe in the value of mistranslation from one tradition to another. So not knowing the tradition of performances of Woyzeck made it much easier for me not to be hamstrung or overawed by them when working on my production of Woyzeck on the Highveld with Handspring Puppet Company (1993); it was my lack of knowledge that made it easy to take liberties and make discoveries with the text that surprised people who knew it very well and who, unlike me, were aware of its long and honorable history.

I think there’s an important place for stupidity in the studio, for not understanding, for giving the non-understood gesture the benefit of the doubt. I like to examine that gesture when it’s had its place and its time to establish and justify itself. It seems too easy to find a theoretical destruction of any idea when it is made, or a theoretical justification of an idea when it is made. I am very skeptical of good ideas, and much more interested in the physical work and what it produces.

IToP

You work collaboratively in your performance work, out of both necessity and choice. How do you like to name your role in a collaboration? How do you like best to function within the collaboration? As a director? Scenographer? Choreographer? Curator? Artist? Does this change when you are working with another artist’s material, say, the texts and scores of an opera, such as The Nose, for example?

WK

Well, I’m the director of the theater productions. And that is to say that the collaborations have to make a space for my uncertainty. When I first started working in theater, with Junction Avenue Theatre Company in a collaborative workshop environment, whoever had the most strident sense of self-certainty, that was the direction we followed. I’d be loath to push an idea because I was very uncertain about it, but, in retrospect, that uncertain idea would have been better than the much more certain ideas. So when I came back to theater, having abandoned it and then gone into film, it was with the view that I would need to defend my uncertainty. There was no longer going to be an equality of input from everyone, I would be the director among the collaborators. I wanted to make, in the workshop and rehearsal and preparation, a big space for uncertainty and indecision.

When I started working with the costume designer Greta Goiris, and she came to me after the first working session and said she was sorry she didn’t have any drawings, any clear ideas, I said to her, “That’s exactly why I wanted to work with you.” I don’t want a costume designer who’s going to come with twenty drawings on the first day of rehearsal—which I would feel obliged to follow, after all that work had been done. I want to have a period of discovery of what the costumes or the set or the video would be.

I’m very careful to choose collaborators who are open to this uncertainty and the tummelplatz of the studio, which is a space of contestation, of play, of jousting, and of discovery.

IToP

How do you develop narrative and image in your performance work? How does sound or the score also play into the development of narrative and the story? Do you feel bound by or engaged with any theatrical conventions—such as narrative arc, character development, or plot resolution—within the creation of narrative?

WK

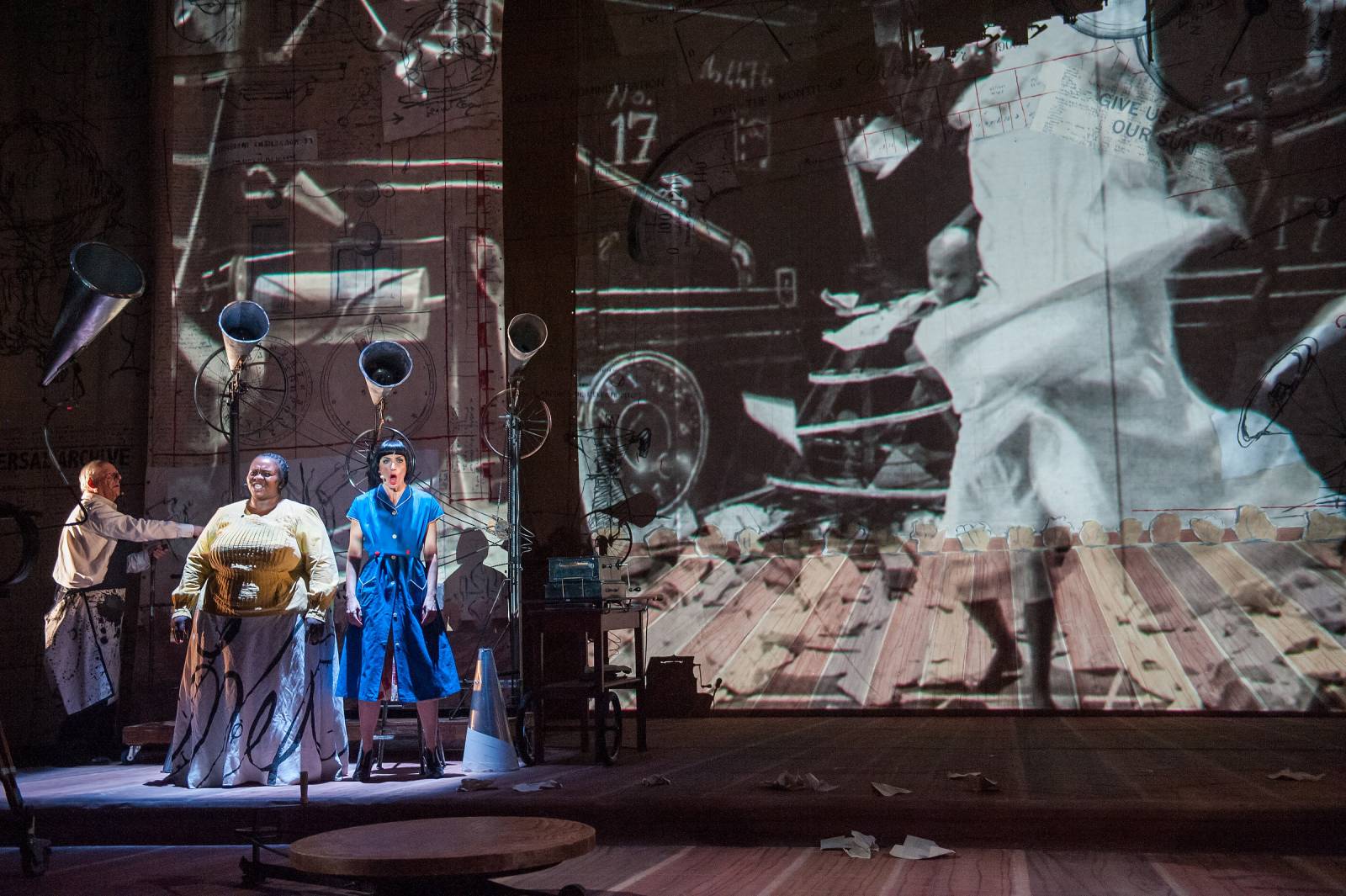

Sound and the score are vital. Working with the composer Philip Miller is a collaboration from the beginning, with music producing images and images provoking sound. Obviously, when working with a given material, like The Nose or Lulu or The Magic Flute, there’s a text and music given, but within that, there’s a whole discovery of the language with which it will be performed, with which the projections will happen. So it’s an exploration, but within very set bounds.

What’s interesting in doing the project is finding out whether the thematic material—the Enlightenment with The Magic Flute, the impossibility of a fixed point of desire in Lulu, the place of the absurd in The Nose—is strong enough to justify working within the constraints of the given text and music.

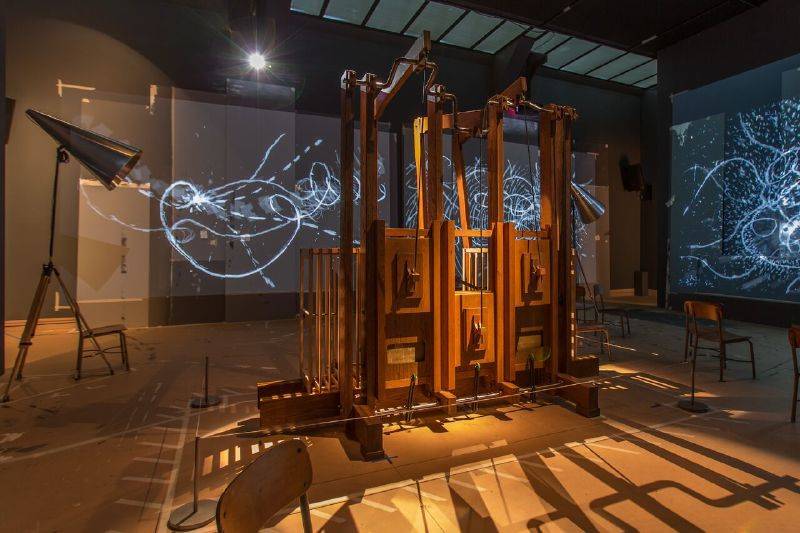

Sometimes I am too respectful of the given text and music, such as when I’m working with an opera house, as I am now. If it starts from the studio outward in something like The Refusal of Time (2012), where there’s no script or music given, a very different kind of production emerges. Both are important for me; I can move from the rigor, the structure, and the machinery of grand opera to the absolute openness of a small group of people working from the studio outward.

IToP

You have talked about your work as “autobiography in the third person.” How does this influence your notion of “character,” or to use another language, “self-portraiture”? How does the “third person” function for you?

WK

It’s difficult for me to define this exactly, but when I’m filming myself, particularly in multiple forms, in the different drawing lessons and conversation pieces and interviews in which I interview myself, there’s a distancing and a separation: I’m acting, and at the same time I’m thinking, “What a feeble actor, why can’t this stupid actor act better?” In the same way, when I write a script, I wish there were a better scriptwriter writing. But in the end, I realize that whatever you produce, whether you like it or not, it is who you are. It becomes a kind of self-portrait, although it’s very different from saying, “Let me look in the mirror and scrutinize and try to understand myself.” It’s trying not to understand myself, giving this other person a set of instructions to see what he can do with it. It is a way of changing the self into the third person.

IToP

With what kinds of artists or art professionals are you most comfortable conversing? Who speaks your language? Those in the visual arts, those in the performing arts? Sculptors, filmmakers, set designers, composers, playwrights, fabricators, actors, critics, curators, producers?

WK

I suppose the people who speak my language are collaborators and friends who understand the links and the jumps. I’ve had very close collaborations with people in the visual arts. The performing arts are by nature more collaborative; there’s a designer, a costume designer, a lighting designer, a video editor, a stage manager, and performers. Speaking to all of those collaborators, those are easy conversations.

Those in the performing arts, in the theater world, understand the nature of uncertainty and doubt. In the opera world, there’s often an assumption that there should be a certainty from the director, the way that there’s a certainty from the conductor about how the performance should be. It’s sometimes difficult to convince singers of the need to not know what they’re doing in the beginning, and for me not to be able to give them clear instructions, but for us to have the five weeks of preparation to discover what we should be doing.

The language of aestheticians, of professional writers on art, is much more difficult for me. There’s a whole world of structuralist and post-structuralist language that I find very foreign. I suppose my theoretical interests are rooted in the 1960s and early ’70s and before, in Habermas and Kojève and the Frankfurt School of Marxism, and writers from that era, rather than Althusser and all the people who came after him. Critics and writers who have been at university much more recently than I have tend to have a whole different set of vocabulary and reference. But the more I hear about them, the more convinced I am of the importance of the philosophical tradition that I am grounded in. I’m much more propelled to curiosity by, say, metaphysical poets than by trying to wade through contemporary philosophical books.

I’m certainly not one of those people who celebrates an anti-intellectualism for artists. Nor do I believe in artists who need to be dumb for critics to write about them. I always said that Clement Greenberg liked his artists to be dumb so he could be the person writing about their work. For me it is important to have a literacy in terms of looking, of having looked at a lot of work, older art in particular. There are a lot of etchings in the field of etching, in which I work; lots of films, in terms of filmmaking. But I must confess I do this looking in a fairly eclectic, not particularly rigorous way. I’m interested in the ideas that emerge after the work is made, not so much in ideas in advance, but in ideas discovered in retrospect, which is essentially what I was covering in the Norton Lectures that I gave at Harvard a couple of years ago.

IToP

Can you describe for us a time when your work either suffered or benefited from a miscommunication?

WK

There are very practical benefits to miscommunication. The first example in my case was when a curator thought that the film I had made should be considered “art” and shown in an exhibition. I was much more conservative than he was and thought that drawings were art and films were film and should be shown at film festivals. So when he wanted to show one of my films in an exhibition among paintings, instead of being delighted, I was insulted. I had to be dragged kicking and screaming into understanding what it was that I had in fact been making. In a similar way, I thought it was a fault when I made bad erasures in my animations, and it had to be pointed out to me that this fault could also be seen as a virtue.

I’m not sure if it’s quite the same as the question you’re asking, but the time that my work benefited most strongly from miscommunication was when I was talking to Reinhold Cassirer, who is a dealer and had a gallery in Johannesburg where I’d first shown work, before I’d gone to theater school in Paris and given up being an artist. He kept asking when I was doing another exhibition, and I kept explaining to him that I was no longer an artist. But he was very deaf and never heard me. About the fifth or sixth time he asked, I capitulated and agreed to do one. So if not for that direct miscommunication, I might well have not gone back into the drawing studio.

IToP

How has the language of performance, the words used to describe it, changed during the time you’ve been an artist?

WK

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, using projections in theater was very unusual, and in opera even more so. Now I’m afraid you can’t go to the theater at all without being bombarded by video projections. So that language around projection and performance has changed. It certainly makes me think sometimes that I want to stop doing projections, except there’s the inherent pleasure of doing them.

IToP

What words most confuse or annoy you?

WK

Trope. Meme. Those would be two.

IToP

Have some terms stayed with you?

WK

There aren’t specific words that I find resonant in the contemporary art and performance world. The words that I keep coming back to: uncertainty, in praise of doubt, the productivity of miscommunication, mistranslation, the virtues of bastardy. But those aren’t the general words of the contemporary art and performance world.

For me, there are a couple of key terms. Overdetermination is one of the important ways for me to understand the gathering of energy around an image or a subject. Then there’s secondary revision, which is a term from psychoanalysis but seems to me vital in terms of taking the work that is made, the drawing that is made, as the given, as the starting point of the concrete material.

IToP

Thank you so much for being part of this project.

WK

It’s been very nice talking to you. I’m sorry this is so wordy.