David Levine

David Levine, an artist working in theater, video, and performance, is Professor of the Practice of Performance, Theater, and Media at Harvard University.

Installation means less today than it used to. In its heyday it referred to a style of art making that, much like performance, threatened to become a genre in its own right: books were written on the subject; Museums of Installation Art were envisioned; artists claimed to specialize in it. Nowadays, of course, hardly any artists refer to themselves as installation artists, just as very few refer to themselves as performance artists. In the twenty-first century installation has been downgraded from a genre to a technique. The art world, furthermore, has expressed a certain discomfort with the term itself, preferring, whenever possible, to describe room-based works as sculpture or, when pressed, as sculptural installation. Ironically (or inevitably?) this has coincided with an uptick in the use of both the term and its techniques in the world of the performing arts.

The genealogy of the term is well documented, as are the technique’s formal roots in the minimalist activation of the exhibition space and, even further back, in the act of hanging the abstract expressionist exhibition and its photographic documentation, the “installation view.” Although art historians locate the roots of installation as far back as Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau (ca. 1923–37), the soi-disant installation really came into its own in the 1980s and early ’90s, with the parafictions of Ilya Kabakov and Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, the synesthetic environments of Cildo Meireles, and the noirish, seemingly abandoned “scenarios” of Mike Nelson. The outlines of the “experience economy” were coming into view, and it was a prime moment for artworks that focused on the viewer’s experience of a total environment.

The problem was that, on closer examination, this experience was always the experience of suspending disbelief. It was one thing to be standing in a bare gallery looking at a cube by Tony Smith; one became acutely aware of one’s separation from both the gallery space itself and the sculpture “activating” that space. But it was quite another thing to be in a total environment by Kabakov or Mike Nelson and having to convince yourself that you were actually of that world, looking for clues to its meaning. And precisely because the tone of these environments was so tasteful—honoring the museum’s promise of quiet contemplation rather than assaulting the senses like a haunted house—it was that much more difficult to believe that you were actually there. Somehow one always felt more real, more ontologically dense, than one’s environment. Thus these immersive works were still generating the alienated, floating spectators of minimalism; only now they were asking you to subsume that alienation into belief. It was as if simply by postulating immersion, artists expected that the art would be experienced as such. But to the extent that the spectator is the real material of installation, the spectator deserved more careful consideration as material. Put another way, installation literalized the anxieties that Michael Fried articulated in his antiminimalist jeremiad “Art and Objecthood”—if minimalism had turned art into theater, installation had turned it into set design.

As soon as spectatorial immersion revealed itself as unconvincing, contemporary art’s antitheatrical impulses began to kick in. Strangely enough, the most elegant way out was advanced by grossout virtuoso Paul McCarthy (a former performance artist himself), not only because the impoverished reality of his early sets was built into their pedigree (they were frequently acquired from TV and film lots) but also because, in contrast to the wall-to-wall environments of Kabakov or Nelson, McCarthy’s structures almost always “floated” within the gallery. That is, he made sure that you could see the outside of the structure before you walked into it and thus could survey it as sculpture—a kind of metastasized minimalist cube—before you entered it as an environment. This maneuver incidentally made a notoriously hard-to-sell art form easier to bring to market; conceived as sculpture, installation was much easier to imagine buying, selling, or exhibiting: you were no longer buying space; you were buying stuff. And the room no longer had to be tailor-made to fit—it just had to be big enough to contain.

Environments, of course, continue to be made, but they are not thought of as installations, and Christoph Büchel, Thomas Hirschhorn, Carsten Höller, and Andrea Zittel are referred to as sculptors or, more generally, artists. Installation, like performance, is something any artist gets to do, indulge in, or resort to once in a while. Unlike painting or sculpture, it is generally not thought of as a medium in which one needs to train or specialize, which has perhaps enabled its adoption by the performing arts.

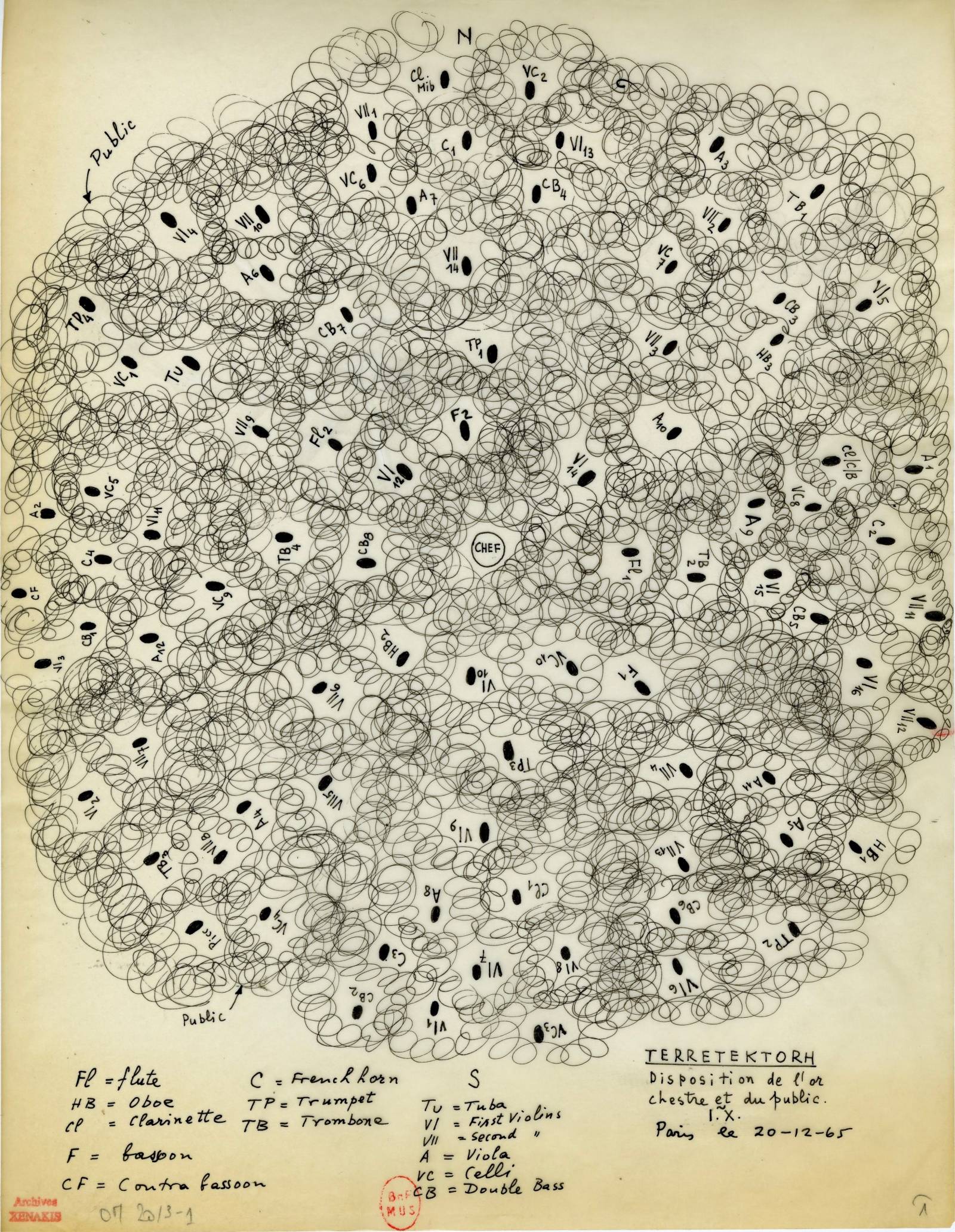

Cross-fertilization between immersive visual art environments and the performing arts has been going on at least since the happenings, and given the way in which spectators tend to experience such environments, this makes perfect sense: one is always aware of the fictitiousness of such environments, and indeed the pleasure to be had from such environments is precisely the pleasure of suspending one’s disbelief. This form of pleasure, anathema to contemporary art, is the pleasure of being at the theater. Traditionally this experience has been confined to the proscenium and its variants, although attempts have been made in experimental circles to create total spectatorial environments since at least the early twentieth century. More widespread adoption of installation as a technique has, however, been stymied by the fact that most theaters just are not built for that kind of environmental experience, so there has been no way to monetize it.

All this changed with the arrival, in the US, of the English company Punchdrunk, specifically with the overwhelming commercial success of Sleep No More, their installation-based version of Macbeth, where spectators wander from room to room of New York’s McKitrick Hotel, encountering various scenarios loosely based on Shakespeare’s play. Sleep No More is, essentially, the apotheosis of installation as an idea. It is what installation art was always waiting to become. Installation art may have been born in the visual arts, but it is finally gravitating toward its rightful home in theater.

For Further Reference

Claire Bishop, Installation Art: A Critical History (Routledge, 2005).

Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (1976).

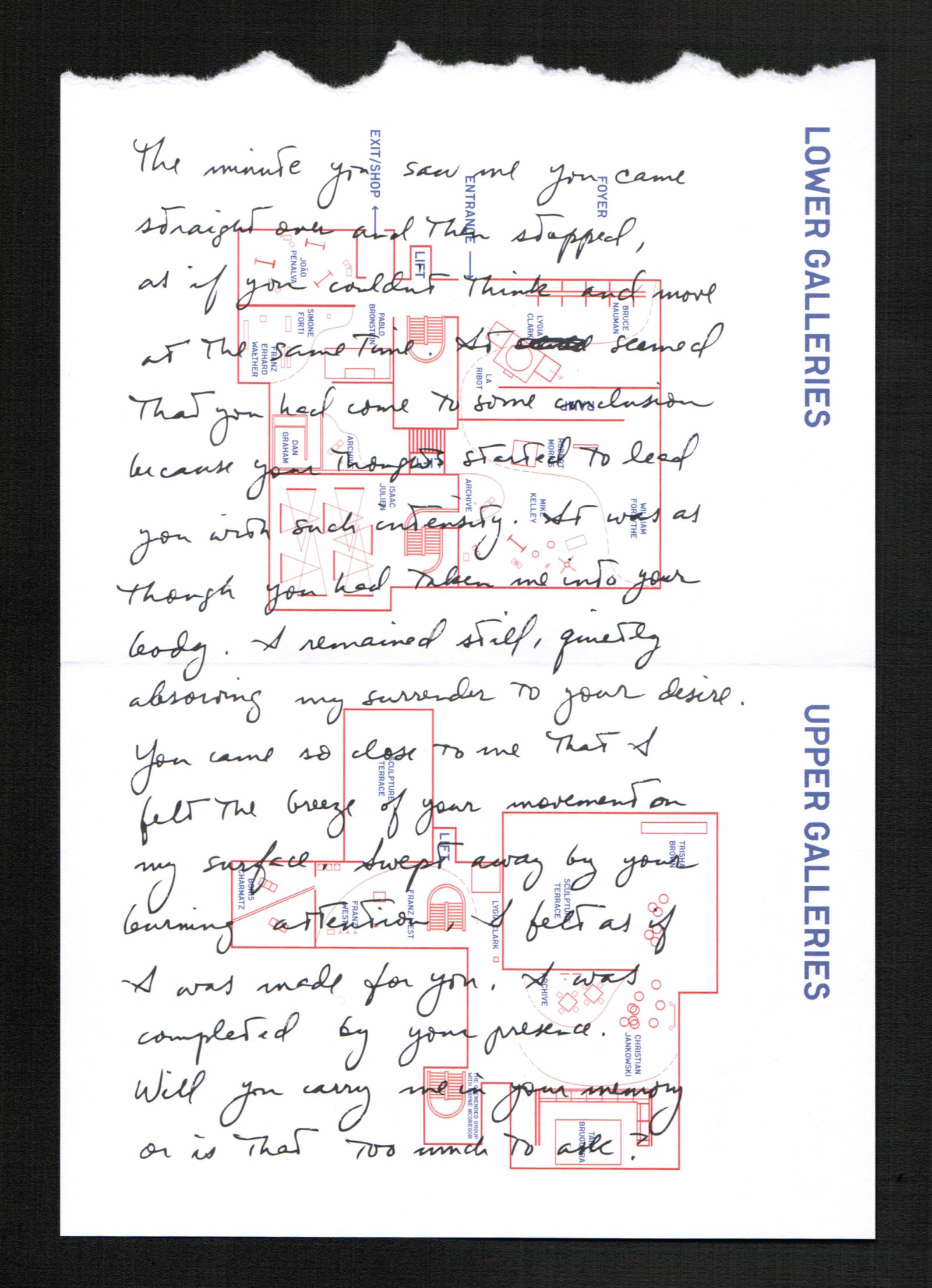

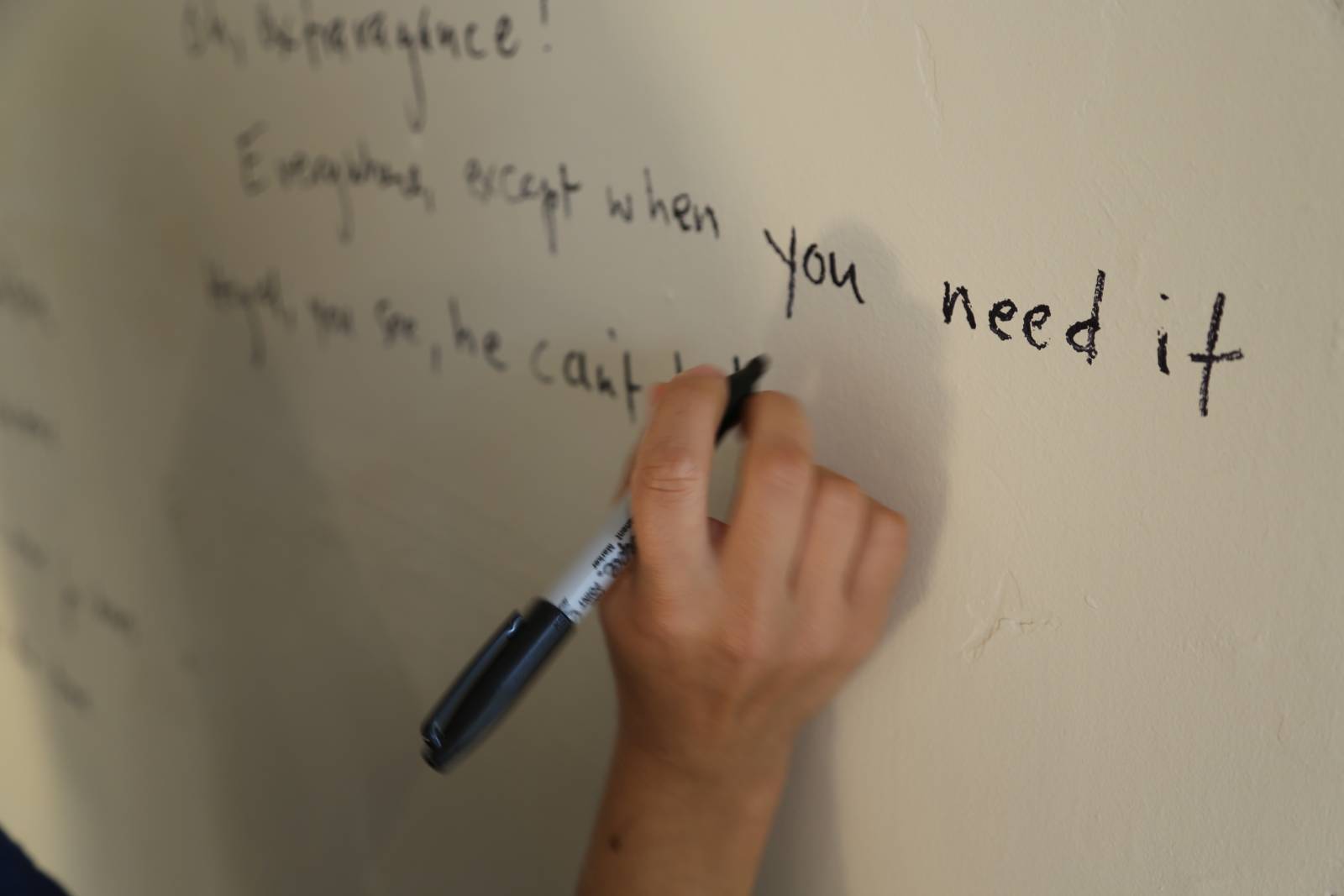

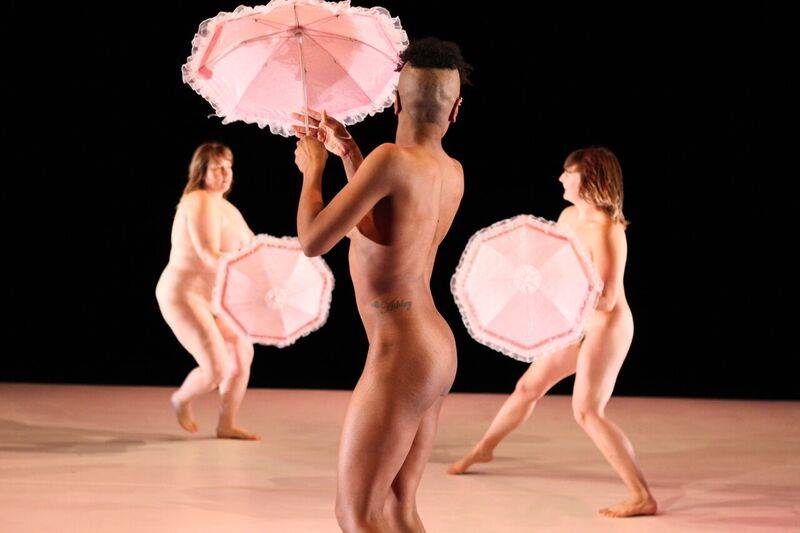

David Levine, Habit, 2011.

Punchdrunk, Sleep No More, 2011.

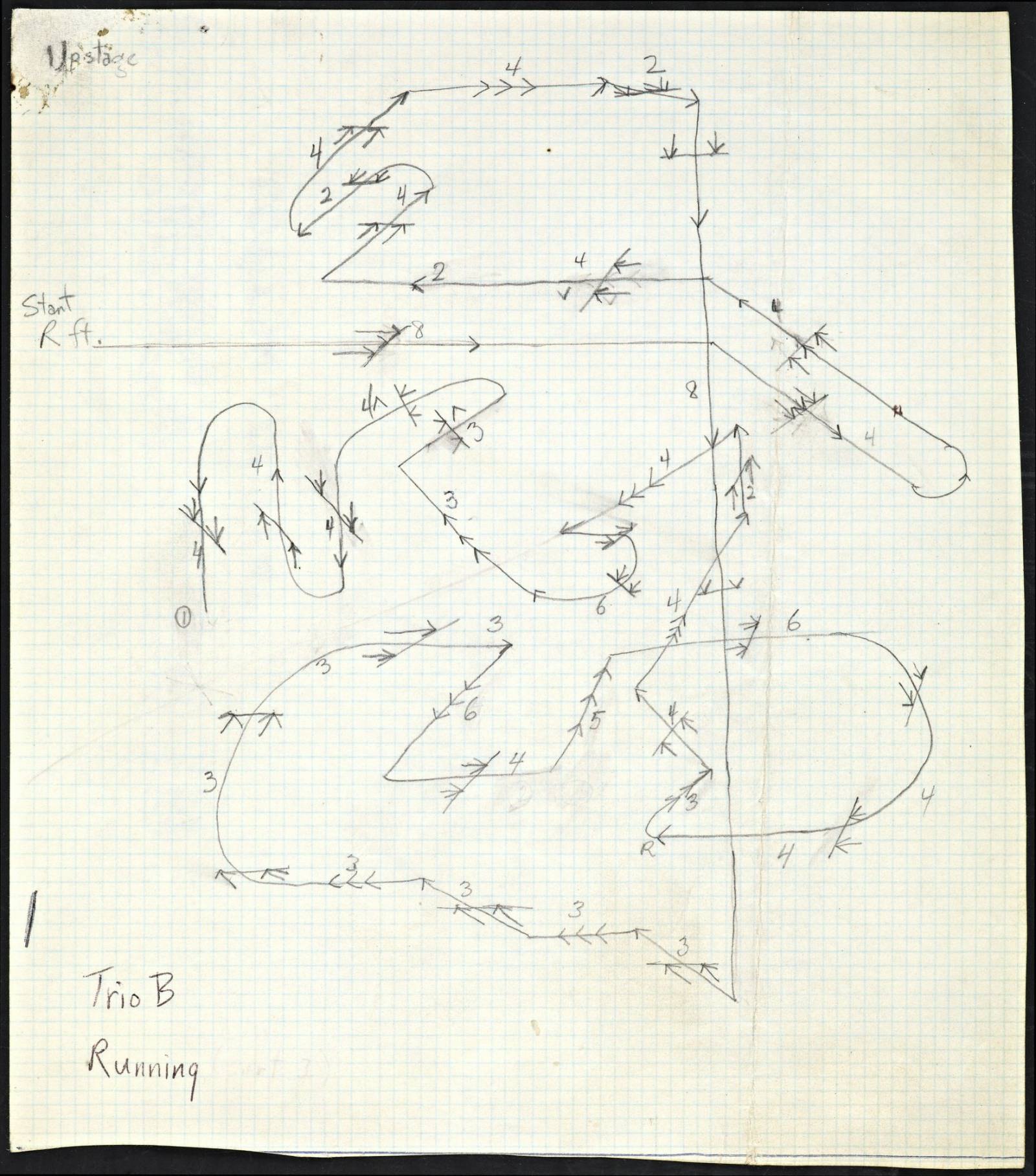

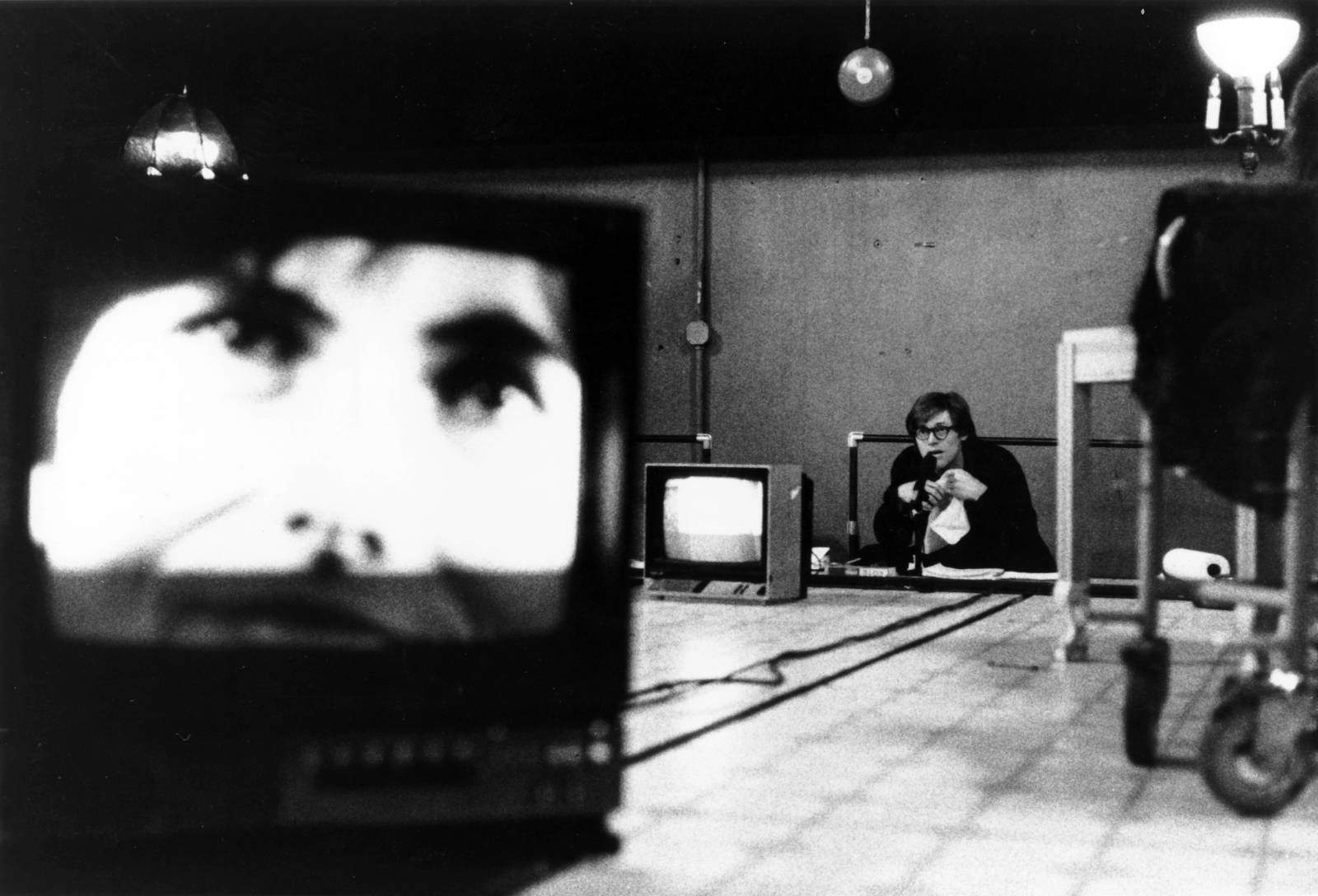

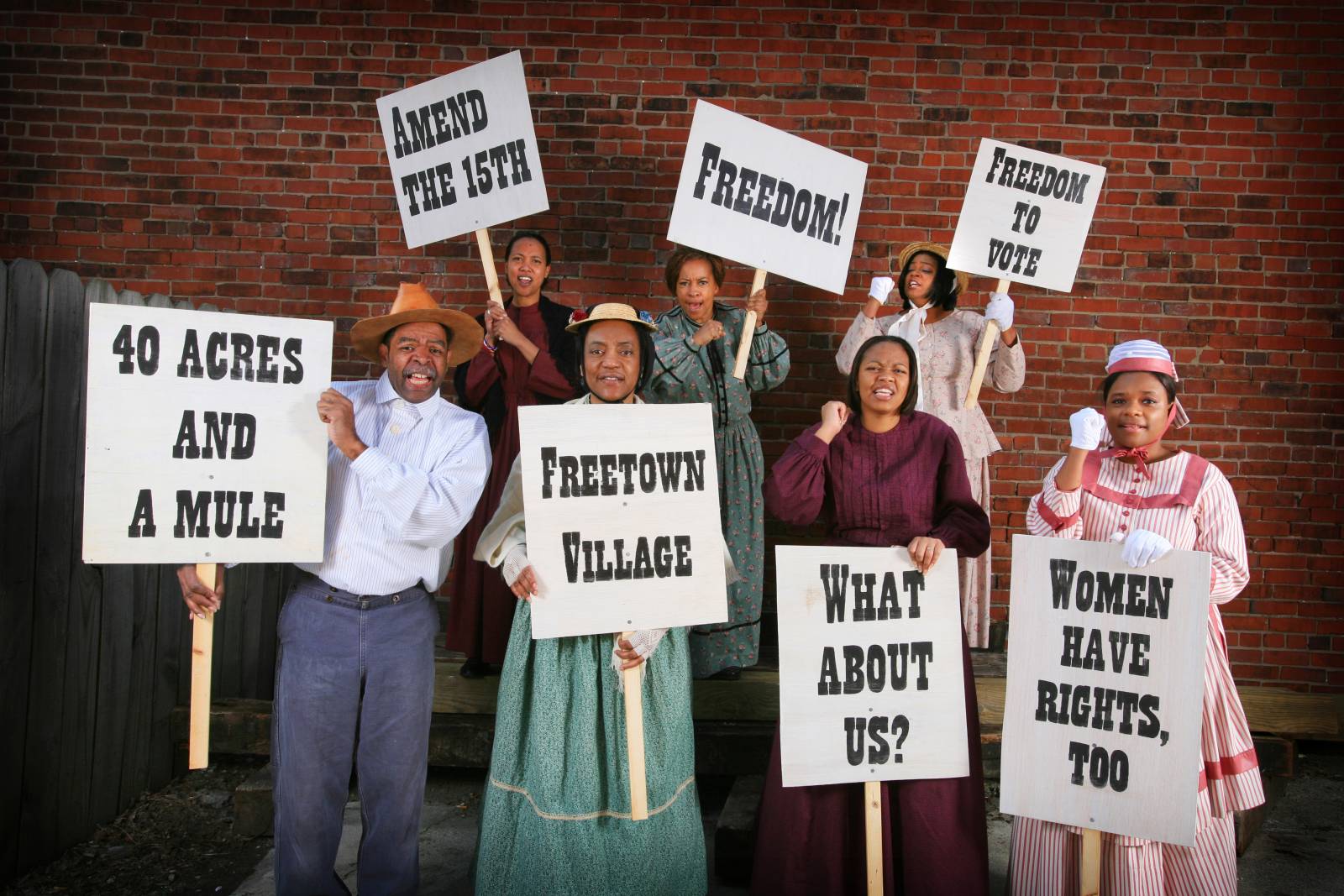

Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, 1959.

Queen of the Night, directed by Christine Jones, Paramount Hotel, New York, 2014.

Paul McCarthy, Painter, 1995.

Ilya Kabakov, The Man Who Flew Into Space, 1981–88.

Mike Nelson, The Coral Reef, 2000.

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, The Dark Pool, 1995.

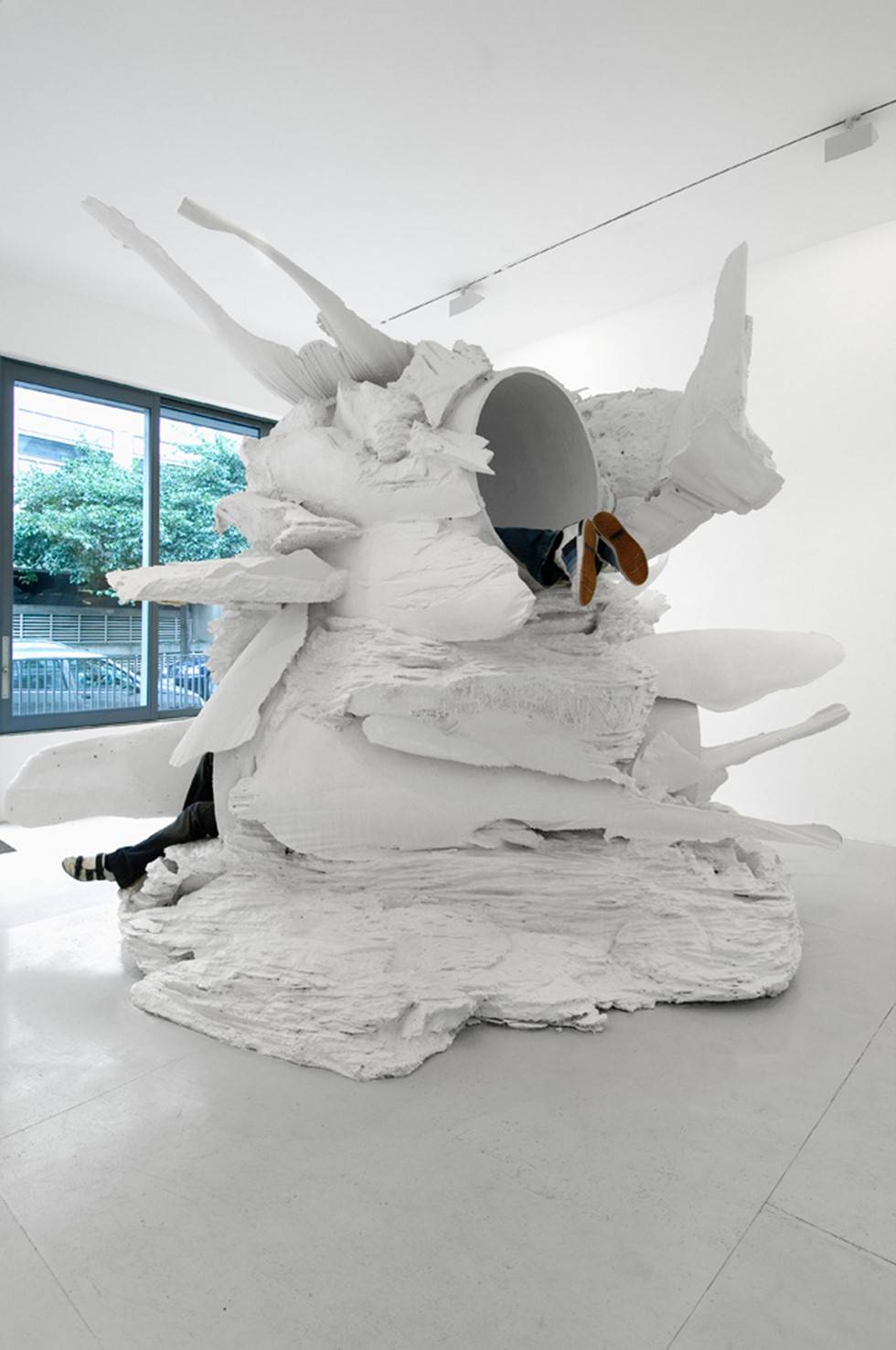

Christoph Büchel, Dump, 2008.

Thomas Hirschhorn, Cavemanman, 2008.