Although the etymological origin of the word participate is straightforward, with Latin roots pars (part) and capere (take)—to take part—it seems that the organic open-endedness of this verb has taken it through at least one other now archaic meaning, which is “to have or possess.” The example given in the Oxford English Dictionary is “both members participate of harmony,” which I find quite apt as a starting point for a meditation on what it means in current artistic practice to participate in a work of art. To what extent do those who engage with an artwork at any stage of its development “possess” something in the process or as a result of that encounter? If someone is taking “part,” does that mean that he or she is part of a whole? If so, what is that whole, and is it all contained in the artwork? Or does it exceed the artwork, including the results of its being in the world and among the people who encounter it?

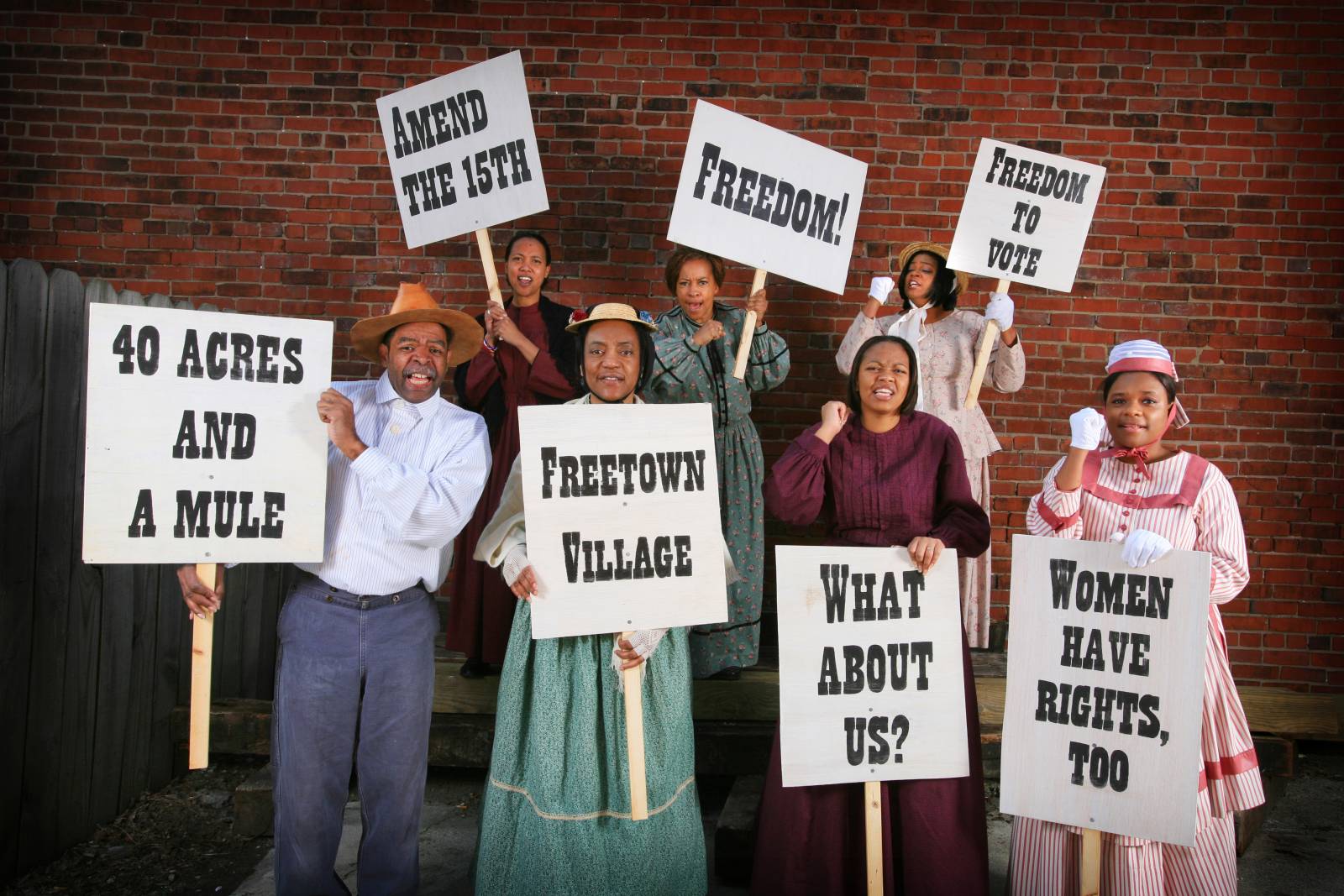

Recent art discourse emphasizes the value of broadening and diversifying the act of “participation” in artistic encounters. Increased transparency of the artistic process can often provoke discussion of new ways for people to participate in funding, building, performing, influencing, or discussing the work; meanwhile its process of coming-to-be is documented, often online. The desire for increased transparency is often understood as part of a demystification of the artist, which is in turn part of a larger cultural movement that seeks to dismantle classic Western hierarchies between artist and receiver and between art and the world around it. Many artists believe that opportunities to “participate” in the process of art making can have a valuable effect on the society in which the artwork comes to be.

Consider, for instance, the large-scale collaborative projects of Christo and Jeanne-Claude in California, Paris, Berlin, and elsewhere. Christo rejects the notion that the meetings and permits and interactions with stakeholders are encumbrances to art-making; rather he insists that all these relationships are an integral part of the artistic process. We could in turn say that the large number of volunteers who come together to help build his various projects are “participating.” This reframing of what constitutes artistic process thus becomes an invitation to view many relational transactions as artistic participation.

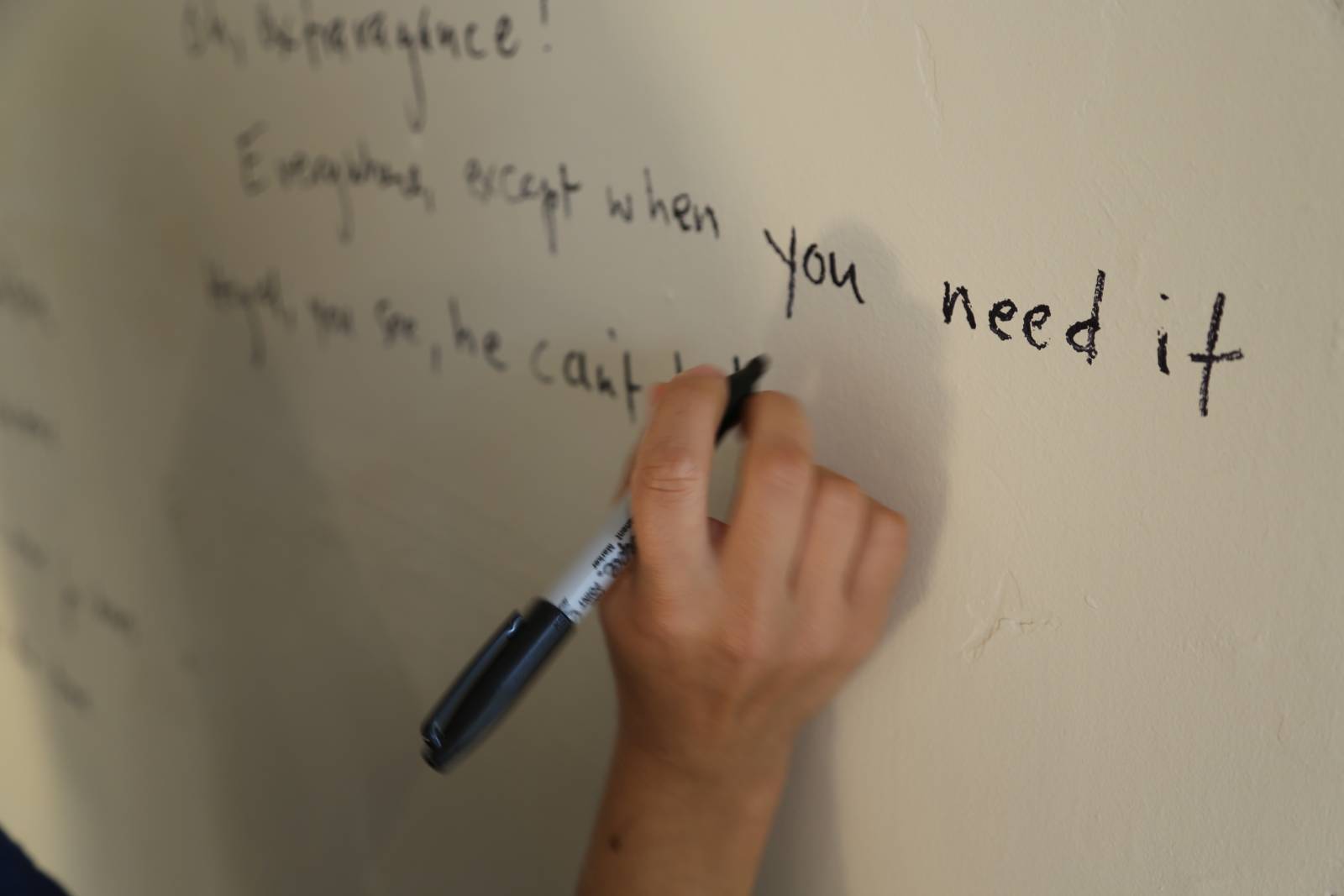

Crowd-sourcing content is another increasingly popular form of enhanced participation in process. In 2006, when I was working on my piece Chance Encounter for performance in transient public spaces, I encouraged those who followed the project blog online to contribute dialogue that they had overheard in such settings. Many of these overheard snippets became part of the libretto of the piece. The use of social media in artistic process and documentation has become much more robust since 2006, and such systems of participation are often an integral part of an artist’s overall project design.

A new emphasis on participation in music is also beginning to overturn traditional notions of what “access” and “outreach” mean. Increasingly, arts-in-education programs (primarily those that are artist-driven) devise and curate new ways to engage students (of whatever age) to participate in the co-creation of what they hear. (Björk’s web-based composition apps for kids are a great example.)

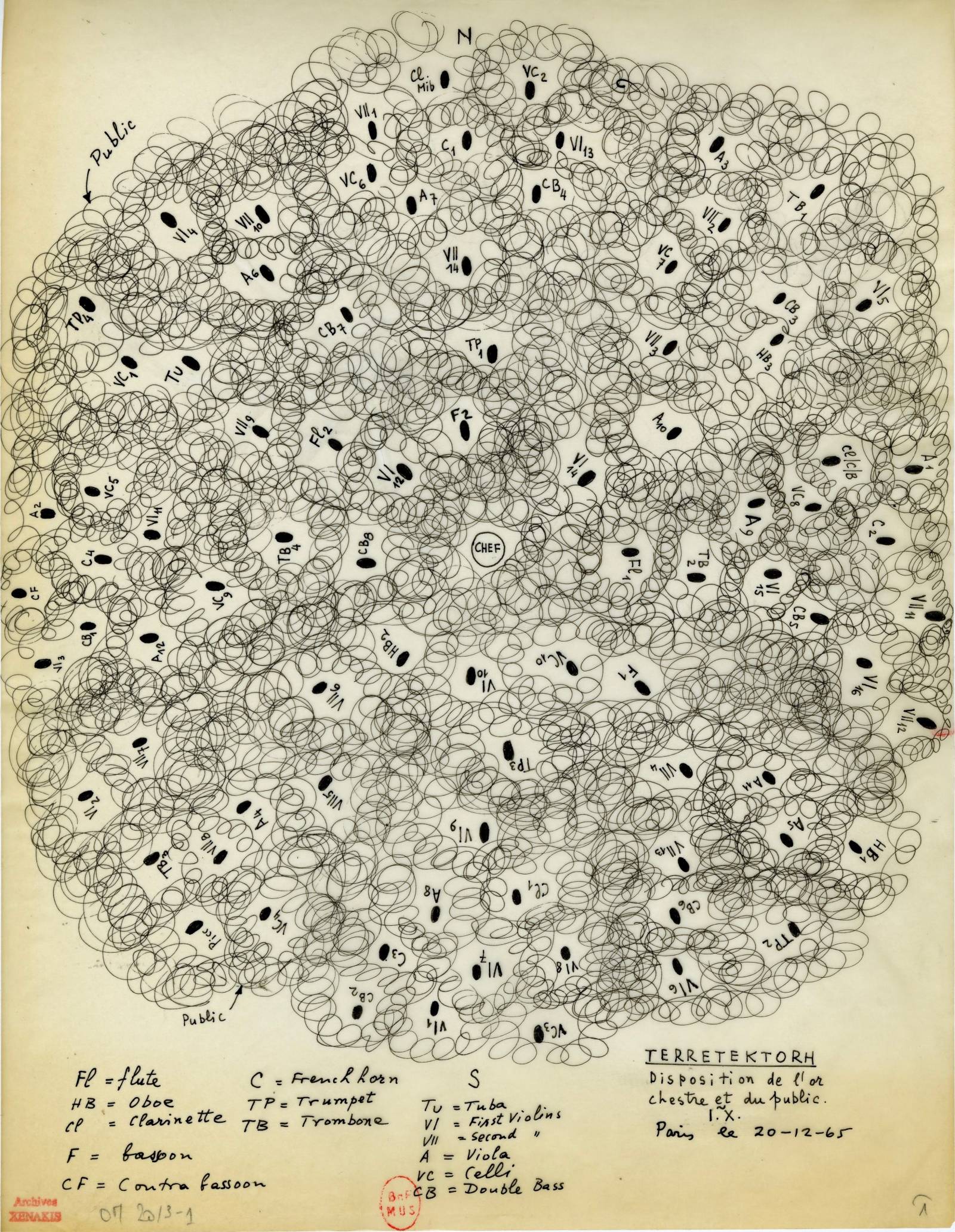

The world of classical music presupposes two defined strata or poles of participation: some people (musicians) participate by playing or singing the music a composer has written, and others (listeners/audience) participate by hearing and receiving. Both of these classes of participants may be enriched by the thoughts and feelings resulting from their relation to the music performed. At the same time, musical instruments require training, and music itself is an entire language that requires serious study; hence polarities of artist and amateur, musician and listener, have been difficult to break down. This tension has stimulated a renaissance among contemporary composers (including myself) of “serious” artworks providing dedicated roles for students, amateurs, and unskilled or lay noisemakers. A great example is the Italian composer Salvatore Sciarrino’s 1997 piece Cerchio tagliato dei suoni (Cutting the circle of sounds), incorporating one hundred amateur flutists. (The US premiere was in 2012, at the Guggenheim Museum, and the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA presented it in April 2015.) My own Airfield Broadcast compositions (2013) incorporate hundreds of student and amateur musicians who are prepared through a workshop process in which music is created expressly for them, at whatever level they can participate.

Other composers explore these tensions through more conceptual means. Some composers seek to reimagine their own relationship, through the musical work itself, to the musicians who play it. Others seek primarily to reimagine the relationship between the musical performance and its audience/listeners.

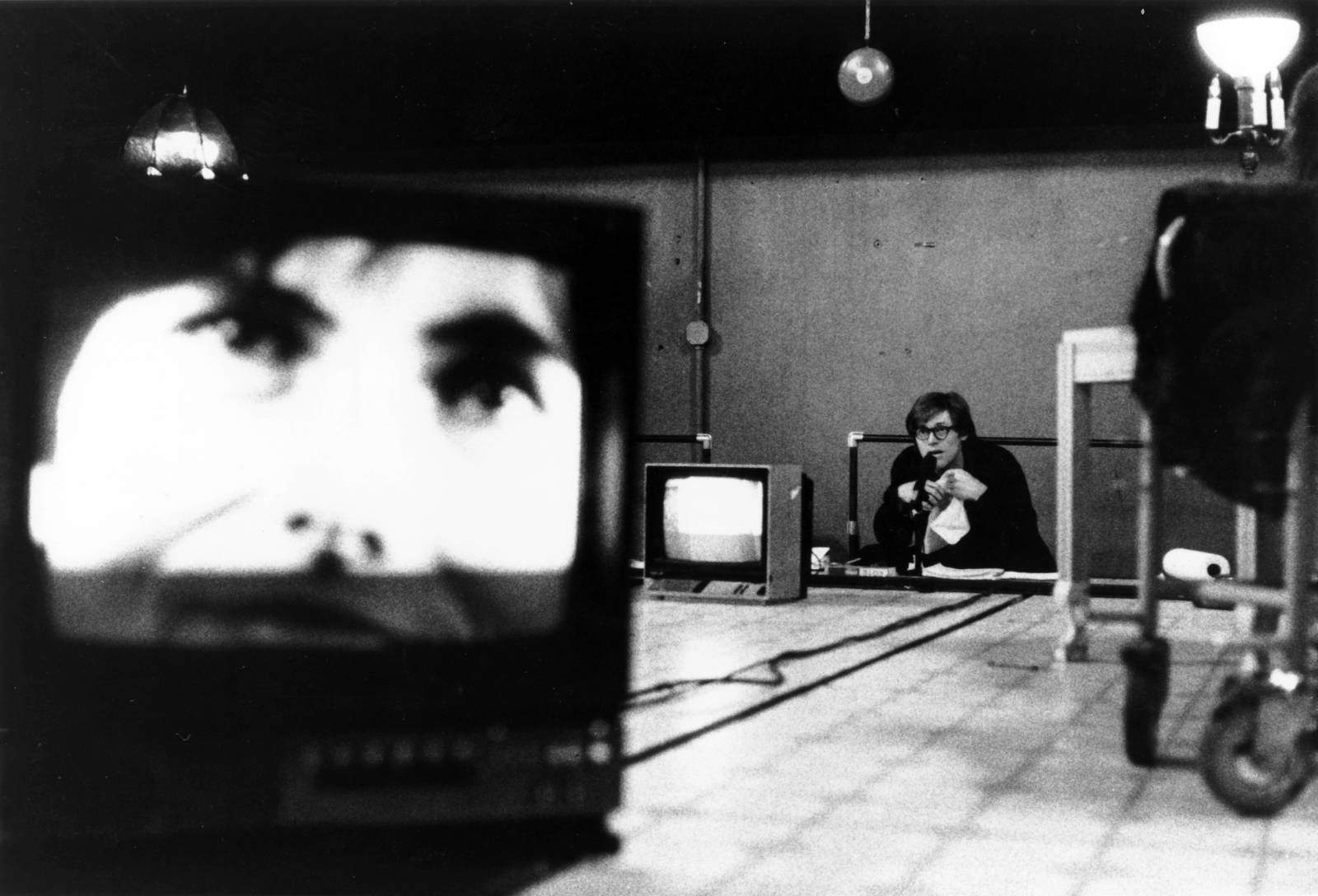

Most famously, John Cage invited us to reimagine both these relationships in his iconic 4'33" (1952), in which the traditional hierarchical roles within musical performance are laid bare precisely through maintaining the vessel (performer[s] with instruments, on a stage, with musical scores in front of them, and listeners poised to hear the performance) while removing its contents entirely. How are the various participants in this ritual “taking part”?

As sea changes in media delivery systems work their way into audience-performer relationships, we artists find ourselves making work that acknowledges ever-evolving means for audience participation. It is precisely at this node—in this case, at the intersection of episodic serial media and opera that my collaborators, director Charles Otte and librettist Erik Ehn, and I find ourselves in our work-in-progress, Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser, which is the first-ever opera created expressly for episodic release via multi-platform media. Who and where is the audience for this work? Those invited “audience” members at the shoots themselves behold the ballet of Steadicam operators, myself and sometimes up to two others conducting (sometimes behind the camera, sometimes on camera), and singers who deliver their performances directly to the camera. Is their participation lesser, or greater, than that of those who view the finished edit? Or is the greatest participation perhaps enjoyed by those who spelunk through KCET’s rich editorial content, including a “Behind the Scenes” segment that has garnered one of the largest numbers of clicks? Is there really any “behind” to these scenes? Ways to participate multiply, and content leaps to fulfill this relationship.

In addition, the format of Vireo itself allows for extremely broad participation by a wide range of musical groups and performers, many of them young people, because each episode is a discrete shoot in an entirely different location. A thrifty cast of thousands, to satisfy the expansive artistic appetites of opera-lovers and binge-watchers alike. (In fact, one might call opera-goers the original binge-watchers.)

Finally, often prophetic in his welcoming stance toward always-greater audience access, John Zorn’s breadth of creative output ranges from sound-based improv through precisely notated orchestral works, and his works are at home on classical, rock, and jazz festival stages. His Cobra (1984), often described as one of the seminal “game pieces” of our time, requires hands-on personal instruction, using cards and gestures that determine ways for assembled musicians to participate in the creation and manipulation of sonic material. The work’s widespread popularity has unlocked a whole world of new ways for musicians at any level to participate in the creation of a musical performance, inspiring a generation to think more creatively about participation.

For Further Reference

Christo and Jeanne-Claude. www.christojeanneclaude.net.

Chance Encounter, 2007–. Composed by Lisa Bielawa; co-conceived by Bielawa and Susan Narucki. www.lisabielawa.net/chance-encounter and www.chance-encounter.org.

Airfield Broadcasts, 2013 (Tempelhof Broadcast in Berlin; Crissy Broadcast in San Francisco). Composed by Lisa Bielawa. www.airfieldbroadcasts.org.

Björk, Biophilia and residency at the New York Hall of Science, with workshops for children.

Silvestro Sciarrino, Cerchio tagliato dei suoni (Cutting the circle of sounds), 1997.

Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser, a project of Grand Central Art Center, CSUF, and KCET. Composed by Lisa Bielawa; libretto by Erik Ehn; directed by Charles Otte, featuring 16-year-old soprano Rowen Sabala. www.operavireo.org.

John Cage, 4'33", 1952.

John Zorn, Cobra, 1984.