RoseLee Goldberg

RoseLee Goldberg, an art historian, author, critic, and curator, is the founding director of Performa, a multidisciplinary organization for the development and presentation of visual art performance.

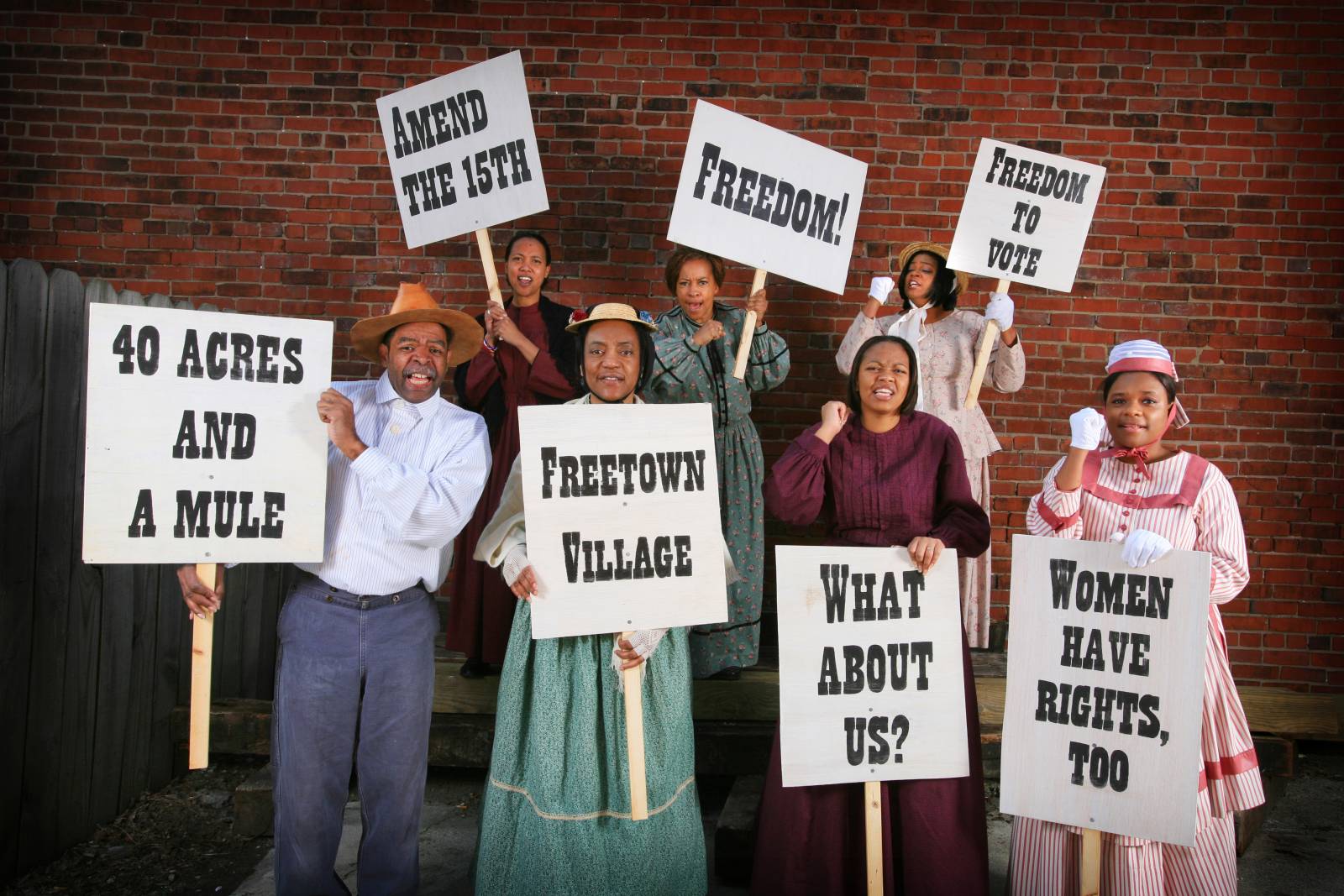

Curating: now that many museums around the world, whether classical or contemporary—from the Musée du Louvre in Paris to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York to Tate Modern in London—have established or are in the process of establishing departments of performance art; are hiring curators to lead those departments; are organizing exhibitions, events, and colloquiums around performance material; and are arranging archives to conserve and protect it for the future, it is clear that there is a need for a new kind of curator to fill these positions. For curating performance demands a level of knowledge and expertise across numerous disciplines that is entirely new to the traditional role of curator, and people with those skills are still few and far between. Since the history of performance art is rarely taught as integral to the history of twentieth-century art, a new generation of curators has yet to be educated. We need to build the extensive reference bank of material necessary for curating, producing, and critiquing both contemporary and historical performance by visual artists.

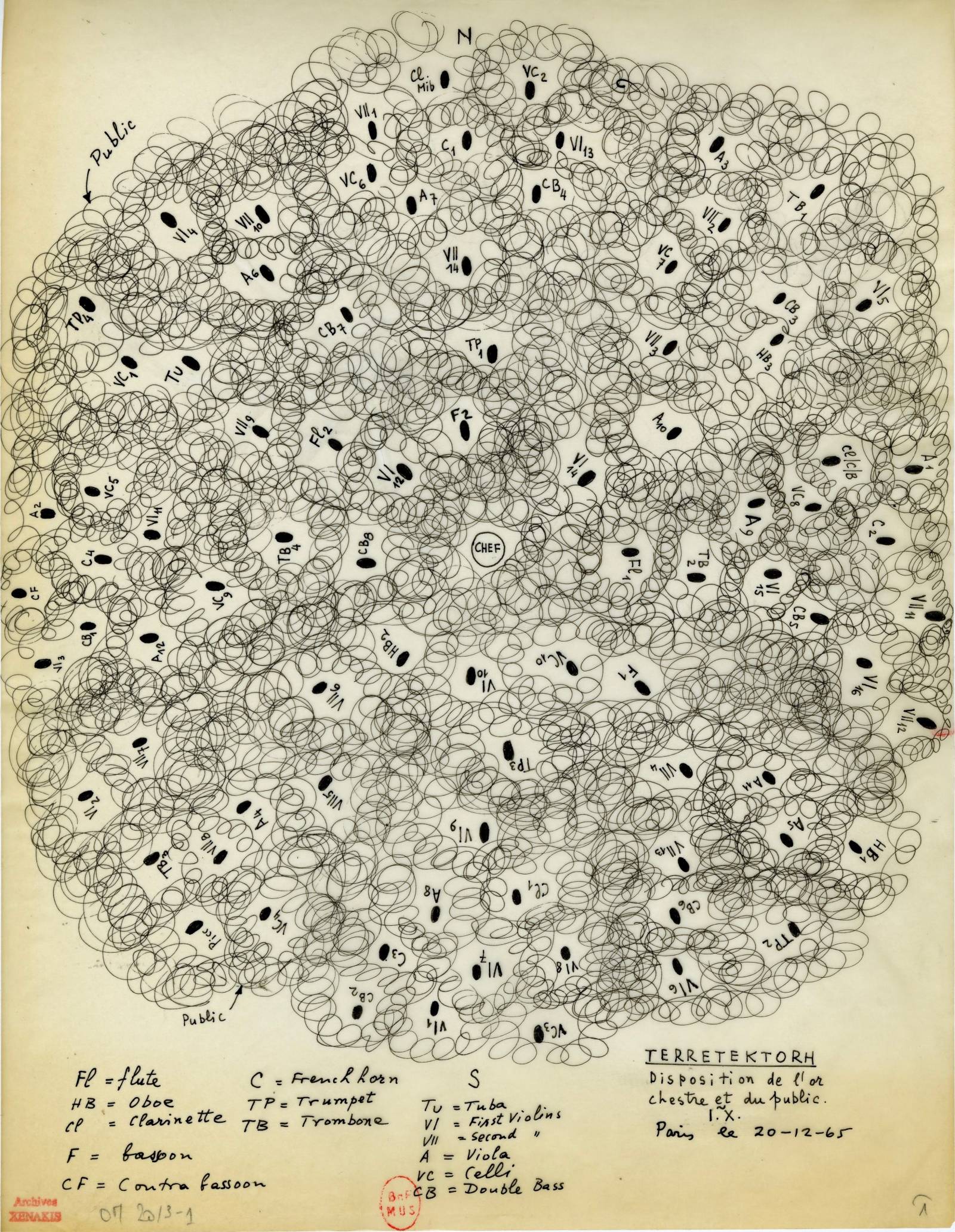

Indeed, the multitiered background required for the analysis of such work includes a broad knowledge of the history of the avant-garde in theater, dance, film, music, architecture, and design as well as a profound knowledge of the history of art itself. Curating an exhibition on Russian Constructivism, for example, necessitates a knowledge of Russian theater, dance, film, architecture, and politics of the years prior to and after the revolution of 1917, in order to trace the roles that each of these histories played in shaping the comprehensive material that falls under “Russian Constructivism.” Similarly, contemporary exhibitions on the Bauhaus, which typically focus on design and architecture, underrepresent its cross-disciplinary nature. It was also notably the first art and architecture school to have a performance space—directed initially by Lothar Schreyer and then by Oskar Schlemmer, himself a dancer, painter, and sculptor—and to offer theater arts in its course prospectus. Curating exhibitions on twentieth- and twenty-first-century art from now on will require the participation of specialized curators from the new performance art departments to fully realize the scope of ideas, influences, and innovative practices within any particular time frame.

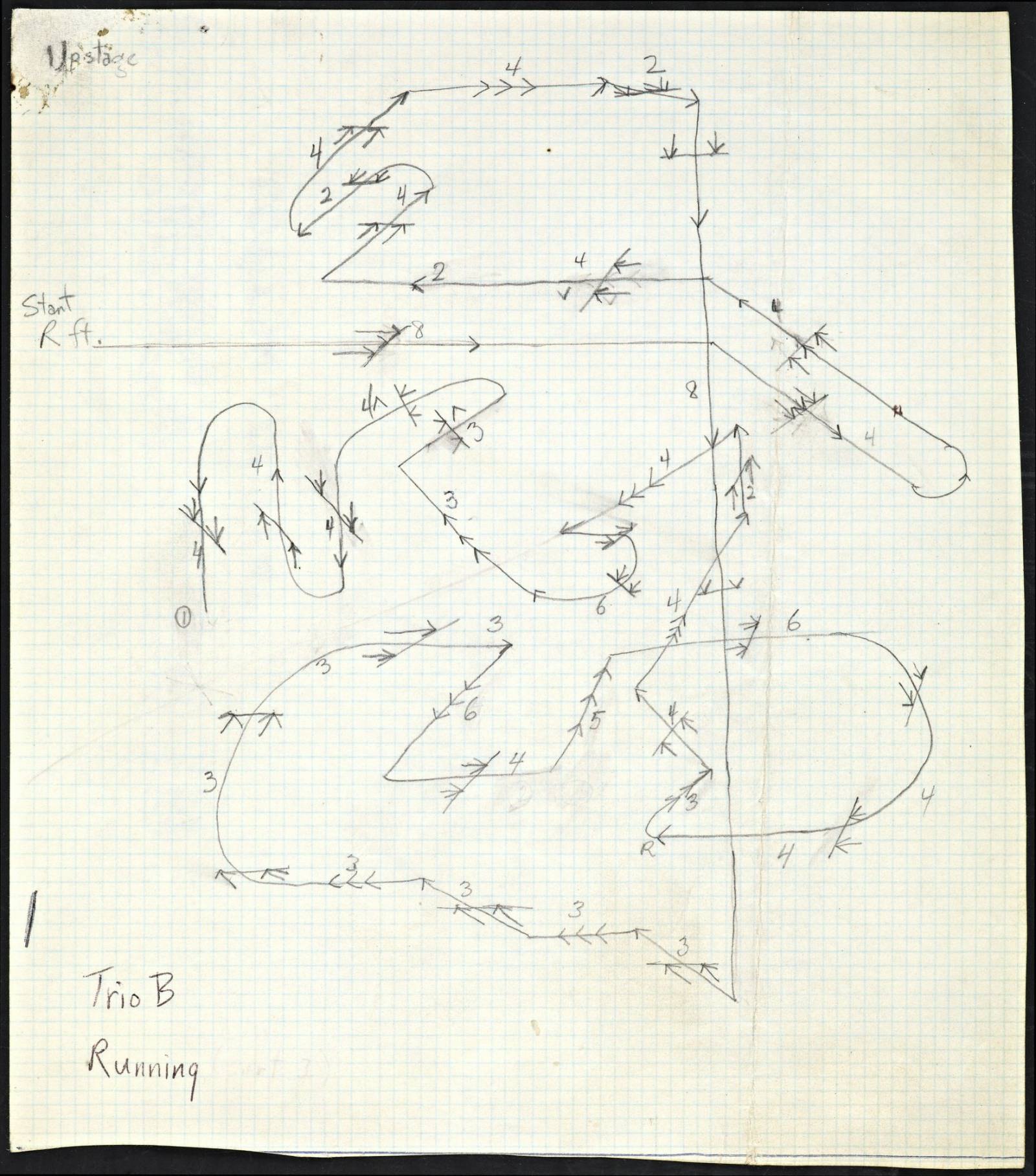

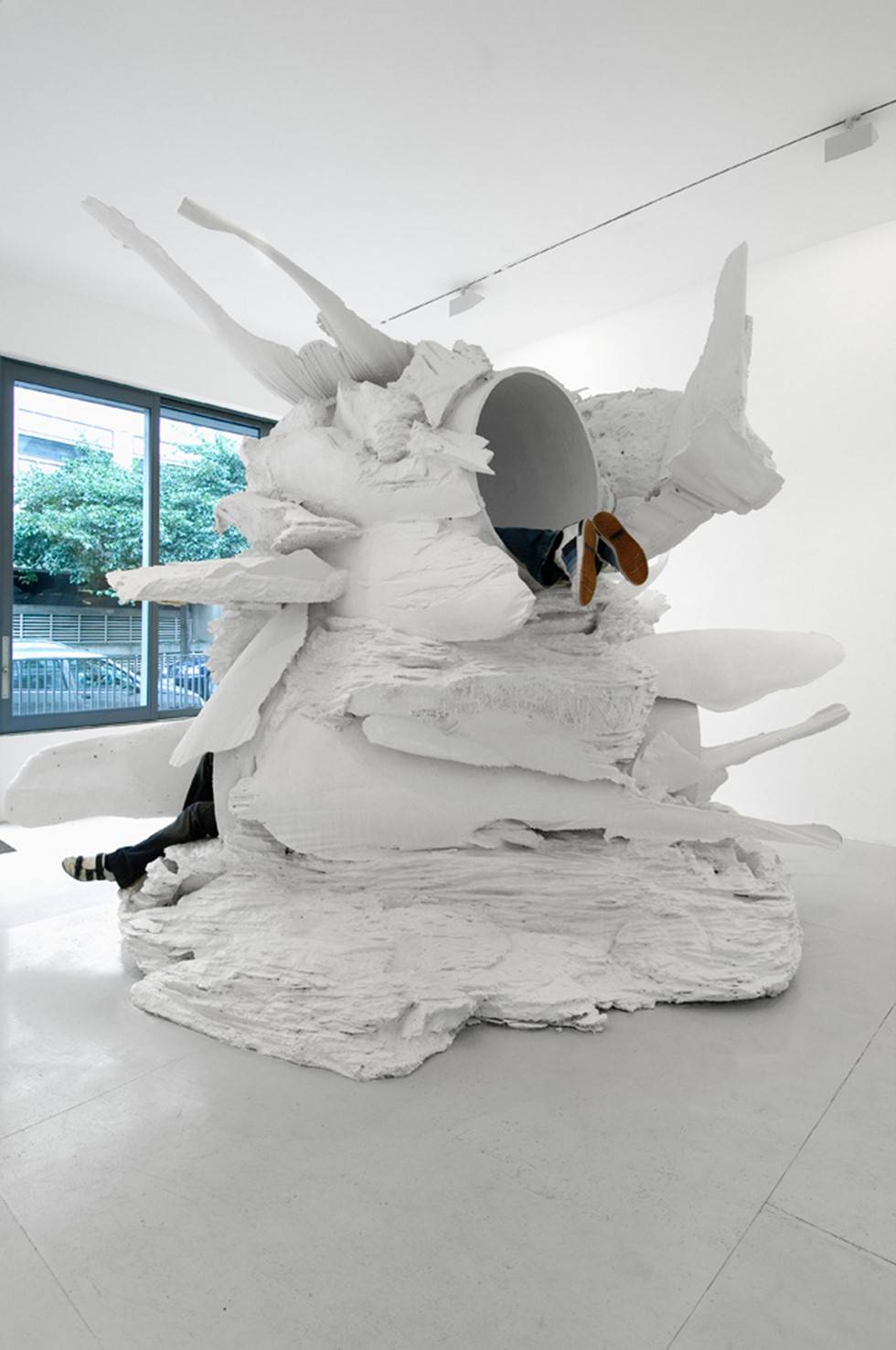

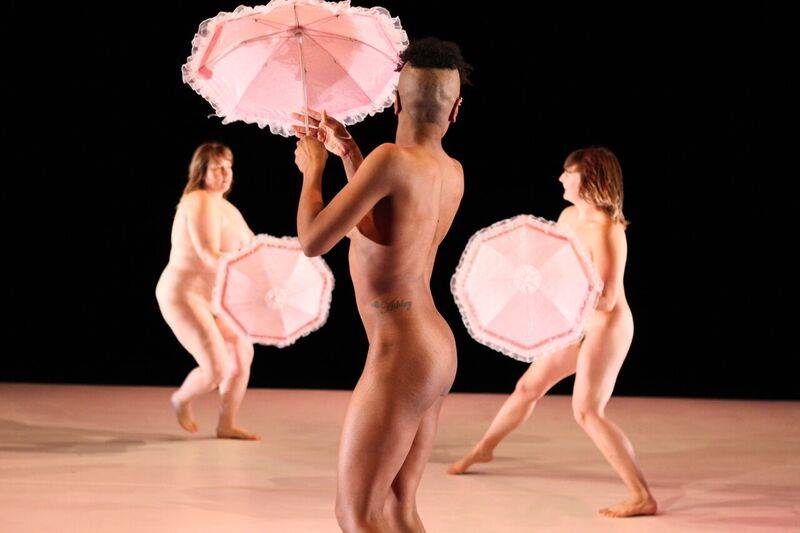

The new curators in performance departments will thus be prepared to incorporate new music, dance, and theater into exhibition programs that are increasingly multidisciplinary. Producing this work in a museum context, however, calls for additional skills over and above the ones associated with the trained curator of visual art; producers need skills honed while working in the performing arts rather than in art museums. The curator-producer must prepare budgets, tech riders, and rehearsal schedules and facilitate sound systems, lighting boards, and greenrooms. The curator involved in producing live performance by visual artists must understand and anticipate the needs of artists working live, which are quite different from those of artists who produce static objects. The traditional curator frames, hangs, and labels work with an eye to visual composition within an exhibition space or a series of linked spaces, articulating the unfolding story of an artist’s work. Meanwhile the curator working with visual artists making live performance must also have an appreciation of time and timing; understand how a work will arc from one moment to the next; know where to position audiences, whether seated or standing, in rows or circles, for optimum experiential effect; and, no less, choose the optimum exit at the conclusion of a work in such a way that the atmosphere and conceptual underpinning of a performance remain with the viewer long after it is over.

Just as a visual art curator will spend long months getting to know an artist and his or her preferences and viewpoints and will incorporate such information into decisions that determine the shape of an exhibition, so too the intricacies of the personal temperament and intentions of the artist working live need to be intimately understood by the curator-producer. An aspect of the dramaturge—an informed adviser with knowledge of the field, who provides overview and context, historical references, criticism, or other commentary—may well fall into the realm of the curator-producer if the artist requires such support. This is often the case with commissions, which involve the curator-producer working in tandem with the artist over an extended period of time, from conception to opening night. Even so, art historical knowledge is essential to the new curator-producer of twenty-first-century performance and media departments.

The curator-producer provides both guidance and interpretation in bringing the artist’s work to the public, along with technical and practical skills to realize the artist’s ideas to the fullest. As both art historian and producer, the curator-producer explains the relevance of the live work within the trajectory of art history as well as its positioning in the oeuvre of the artist, which are important ongoing considerations for artists who look to the ideal curator as both mediator and champion of their work. With such a complex overview of contemporary culture and history, the curator of the future will indeed be a fascinating hybrid: an art historian, producer, tech-savvy intellectual, and innovative thinker who can work closely with artists in a number of different mediums, who can situate the work in a historical continuum, and who can draw on visual intelligence and practical training to create accessible and insightful platforms for audiences across the globe.

For Further Reference

“Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949–1979,” curated by Paul Schimmel, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1998.

“A Little Bit of History Repeated,” curated by Jens Hoffmann, Kunst-Werke, Berlin, 2001.

“A Short History of Performance,” Part 1, curated by Iwona Blazwick, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2002.

Marina Abramović, “Seven Easy Pieces,” curated by Nancy Spector, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2005. Presented as part of the first Performa biennial, Performa 05.

The Performa Biennial, New York, established in 2005, and presented every other year since 2005. Founding director: RoseLee Goldberg.

“Il Tempo del Postino,” curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Philippe Parreno, first presented at the Manchester Opera House, 2007, commissioned by the Manchester International Festival.

“The World as a Stage,” curated by Catherine Wood and Jessica Morgan, Tate Modern, London, 2007–8.

“100 Years,” curated by RoseLee Goldberg and Klaus Biesenbach with Jenny Schlenzka, 2009. Venues: Julia Stoschek Collection, Düsseldorf; MoMA / PS1, New York; and The Garage Center, Moscow.

“Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present,” organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2010.

“Move: Choreographing You,” curated by Stephanie Rosenthal, Hayward Gallery, London, 2010–11.

“Performance Now,” curated by RoseLee Goldberg, 2012. Venues: Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT; H&R Block Artspace, Kansas City Art Institute, MO; Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, Moscow; Middlebury College Museum of Art, VT; Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE; Kraków Theatrical Reminiscences, Poland; QUT Art Museum, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

“Le Mouvement: Performing the City,” curated by Gianni Jetzer and Chris Sharp, 2014, Biel/Bienne, Switzerland.