Rudolf Frieling

Rudolf Frieling, formerly curator and researcher at ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany, is curator of media arts at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

We all actively participate in smaller or larger communities as individuals, professionals, or members of the public. But when we talk about participation in art, an implicit assumption is challenged: the artist produces art and the public contemplates it. When the public is invited to contribute to or coproduce an artwork, this artistic proposal corresponds to a need to question authorial control in a fundamental way. This is a promise as much as it is a problem. While the public hopes for transformative encounters in art, the will to embrace whatever happens in an open and public process may translate into a serendipitous experience or into a failure to produce anything significant. Tearing down the walls of an aesthetically controlled environment, these proposals are still based on formal, aesthetic, and conceptual decisions. By embracing chance, by inviting others to participate in the production of the artwork, by claiming the radical dismantling of traditional systems for evaluating art, artists face a paradox: How to provide conditions for a moment of rupture but also serendipity as an opening of the senses toward an engagement that could reveal the participants’ behavior to themselves as well as to the public and possibly produce an unexpected new set of behaviors? Whatever happens, it happens only when the public is activated. While one might simply contemplate others participating, the artistic experience is intrinsically linked to the very act of participation. At the same time participation will be eternally countered by nonparticipation, indifference, or even resistance.

To speak about the promise of participation in art today means to be aware and critical of its spheres, specific conditions, limitations, and hidden agendas. Some participatory works refuse market-driven commodification by being productive generators of processes that all share a dialogical condition. A topology of the early history of participatory art from the 1960s includes group actions as therapy (Lygia Clark and her “relational objects”), poetic instructions in the tradition of Fluxus (George Brecht and Yoko Ono), communication and media events (Marta Minujin), social sculpture (Joseph Beuys), or simply the reconfiguring of modular elements as a sculptural proposition (Charlotte Posenenske). In each case a context is chosen and formal parameters are set in order to activate a latent and possibly transformative potential.

The history of participation in art encompasses a variety of conceptual, performative, and political approaches, including happenings, shared experiences, and performances as well as activists’ interventions, social practice, and technological communication events. None of these approaches were initially embraced by the art world; in fact even critics, curators, and artists have often proven derisive of participation. Consider, for example, Bruce Nauman’s dictum “I mistrust audience participation.” Or, more recently, the response to the surge of participatory museological practices embodied in The Museum of Non Participation, a fictional museum by the London-based artists Karen Mirza and Brad Butler that questions conditions of political involvement. These and other nonparticipatory projects turn away from political realities as a form of resistance and noncompliance or as a broader dismissal of participatory engagement as part of an uncritical “experience economy” and a neoliberal culture of spectacle.

Participation in art in its most minimal form constitutes a dialogue between the artist and the public; in its most complex form it involves crowd-sourced production processes that are initiated only by artists. Yet participation and dialogue are not intrinsic values. Who is talking to whom about what and in what way? What is being coproduced? When an artwork is subject to public intervention, it does not necessarily become more meaningful or aesthetically charged. To engage with a work requires being intrigued or challenged by its implicit and explicit rules of behavior. When these are violated, the responsibility of the participants is dramatically exposed. A participatory work thus needs an environment that stimulates a balance of trust and responsibility. The audience’s exploitation of proposed situations and the total absence of participation are possibilities inherent in the potentiality of participatory art. Yet the extent to which a work generates an engaged understanding, as opposed to the provocation of an end, may be considered a measure of its participatory quality. What is then experienced as the actual work is the extent to which activation, communality, or antagonistic forces become manifest.

Artists such as Hans Haacke and Stephen Willats have often addressed issues of control, deliberately limiting participation to a predefined set of choices through, for example, voting or multiple choice. Other artists, such as Andrea Fraser, choose to address the supposedly passive audience directly, activating that “medium” in a very physical sense, following the educational model of Bertolt Brecht or Joseph Beuys. This practice of institutional critique to dissect the power regimes and ideological structures that “frame” the art, however, doesn’t reflect on the public’s actual use of the museum. Despite the structural conditions of the institutional setting, the audience is never passive but rather is constantly adopting tactical ways of using the museum. Following Michel de Certeau, these subjective practices that interfere with any prescribed notion of consuming art can be described as “weak.” In the museum context, weak tactics include drifting through an exhibition, distracted attention and simulated contemplation, secretly or openly taking pictures, chatting on the phone, engaging in social interactions rather than simply looking at art: a “fleeting and massive reality of a social activity at play with the order that contains it.” It is only through these personalized actions that the museum becomes what de Certeau would call “habitable”—a “space borrowed for a moment by a transient.” In other words, the public always participates in the experience of art in time and space through its unique and particular ways of dealing with these conditions.

Other artists (e.g., Erwin Wurm) have developed accessible yet also absurd and playful practices involving participatory actions to posit a profound ambiguity, provoking ”weak” responses to the institution and the production process. By refusing to control such engagement or channel specific readings through didactic exhibition paths, a museum offers a space for undefined interactions that radically change our perception of the institution so that it is transformed from a deadening container to a “living museum,” as envisioned by Alexander Dorner in the 1920s. From this perspective the participatory museum becomes a producer of and an arena for social and aesthetic experiences that generate a discursive public space.

For Further Reference

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, 1965.

Lygia Clark, Dialogo/Oculos [Dialogue/Goggles], 1968.

Tom Marioni, The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends Is the Highest Form of Art, 1970–2008.

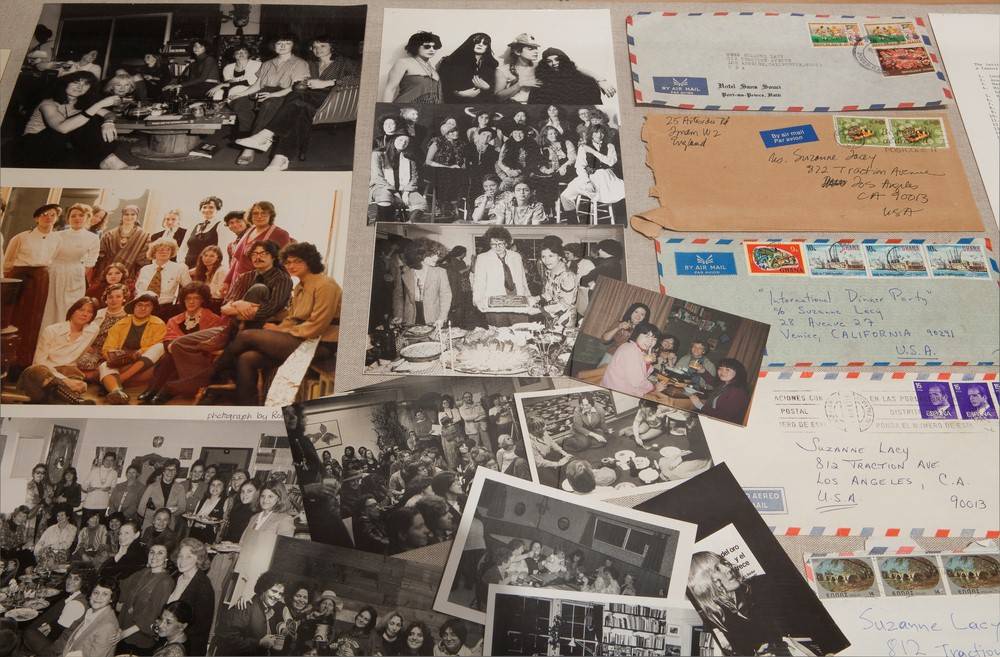

Suzanne Lacy and Linda Pruess, International Dinner Party, 1979.

Robert Adrian X, The World in 24 Hours, 1982.

Erwin Wurm, One Minute Sculptures, 1997–.

Jochen Gerz, The Gift/San Francisco, 2000/2008.

Harrell Fletcher/Miranda July, Learning to Love You More, 2002–9.

Sylvie Blocher, Je et Nous [I and Us], 2003.

Rivane Neuenschwander, I Wish Your Wish, 2003.