To collect simply means to assemble, accumulate, or group together items that are seen to have a connection, to be something of a whole. Visual-art museum collections, ideally driven by precise acquisition policies, try to make sure that a purchase or an accepted gift fits into a larger narrative that the institution is trying to present through its collection. It is hoped that each new object has a relationship not just to art history but to the other objects in the collection as well.

Until recently, museum collection committees and associated curators thought that the real-time, ephemeral nature of performance rendered it “uncollectible,” thus leaving a big part of recent art history unexamined and therefore undervalued. While the twentieth century was chock-full of conceptual and performance-based art practices and the disciplines of visual art, music, dance, and theater were at key moments intertwined and mutually influential, the resulting “live” works were generally collected only when there was a strong physical component that demonstrated value. Value could be historical (determined to be important artistically and worthy of being preserved and displayed into the future, long after the creators and/or original performers were gone) or monetary (able to be bought or sold) or, ideally, both. Yes, material aspects of works by artists such as Joseph Beuys, Yves Klein, and Yoko Ono and the work of the Fluxus, Gutai, and arte povera artists, among others, were actively collected and shown but often stripped of the performative context from which they sprang.

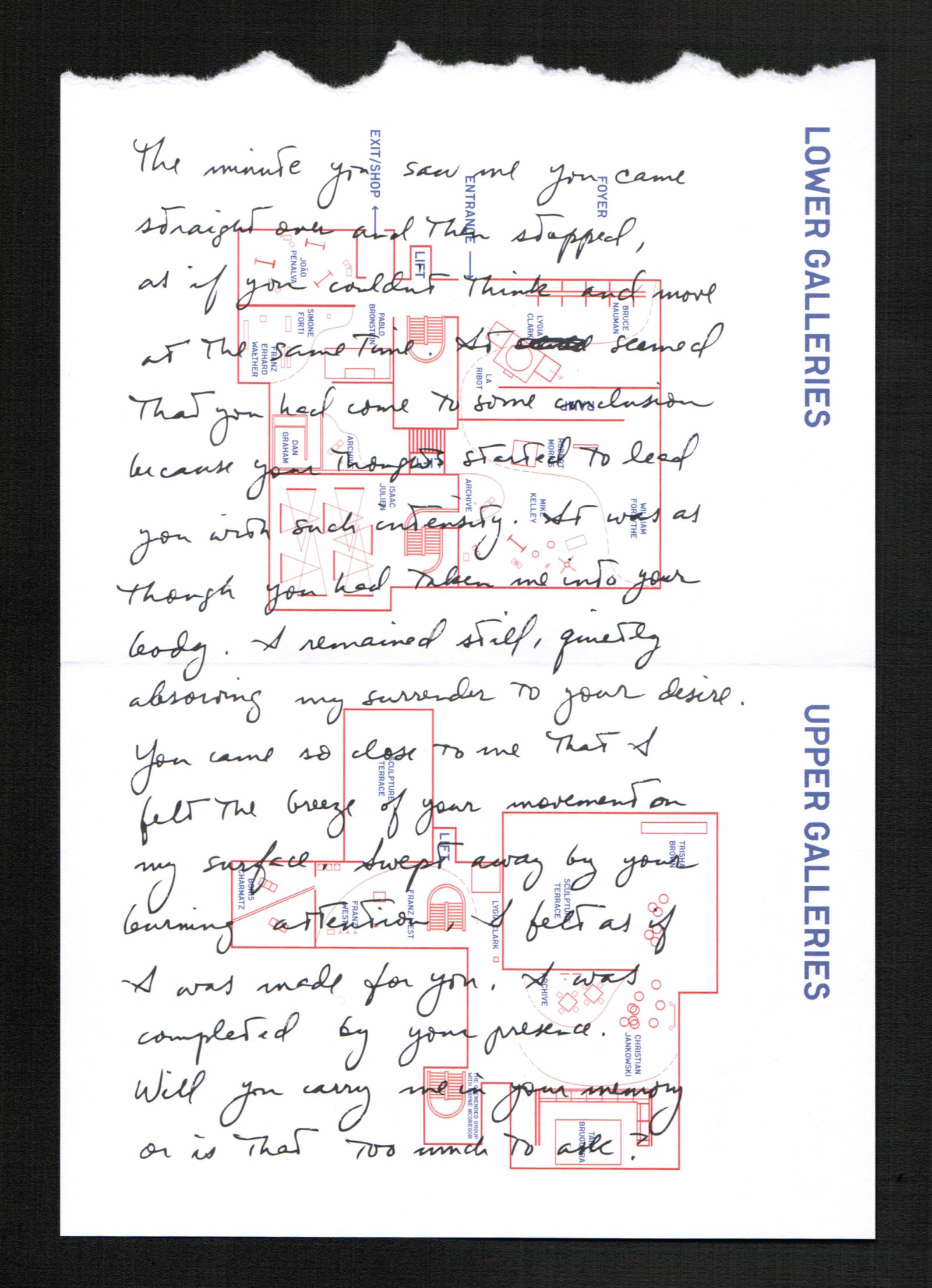

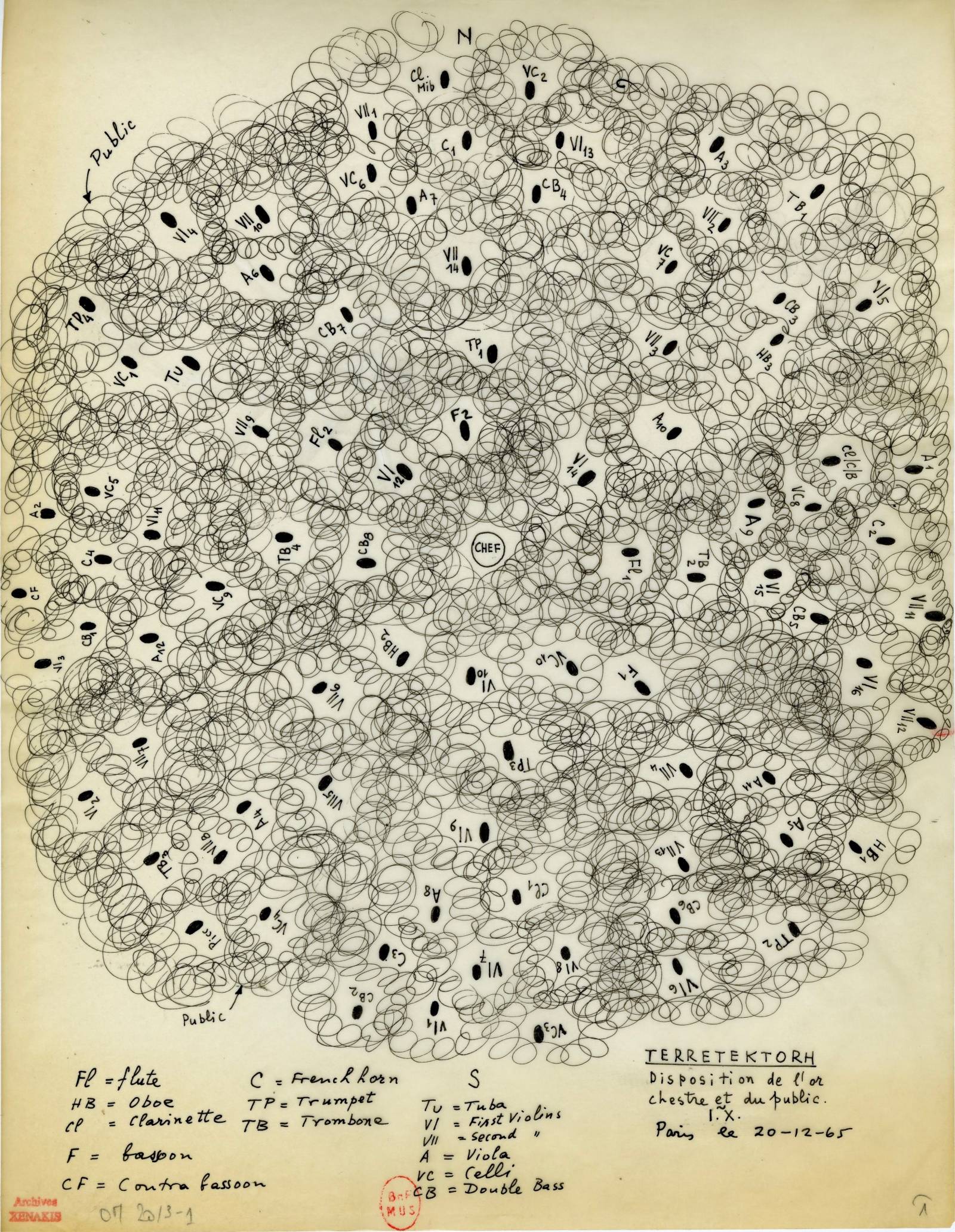

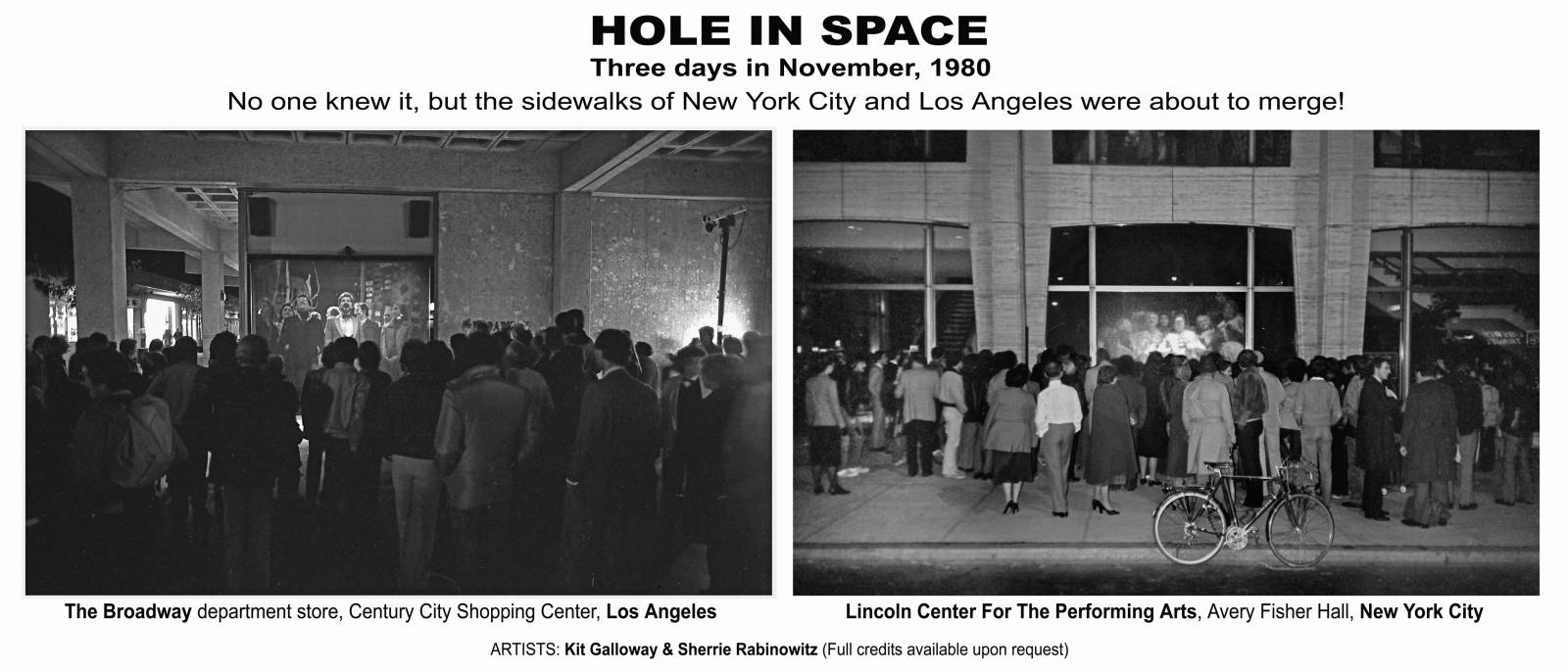

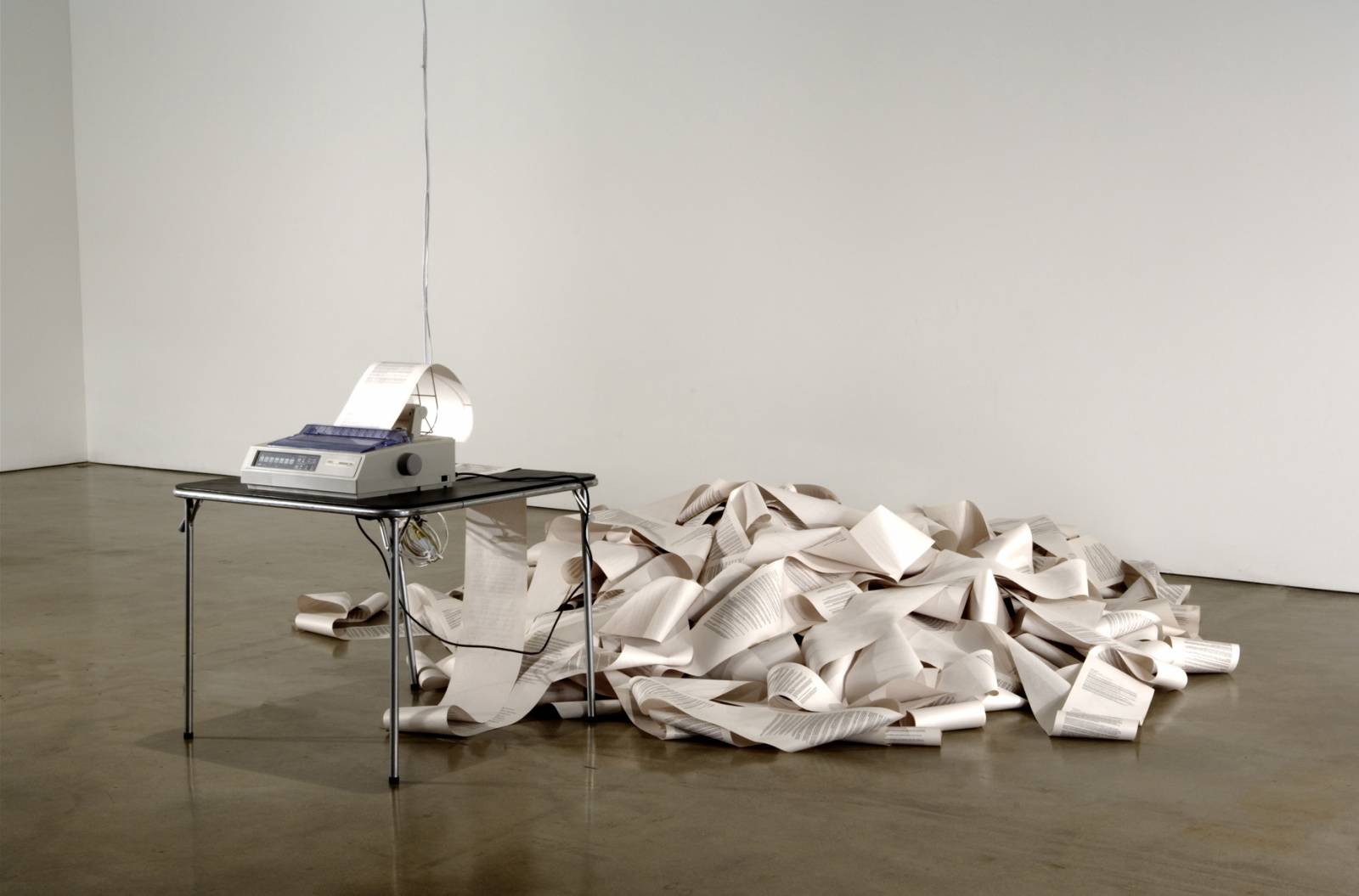

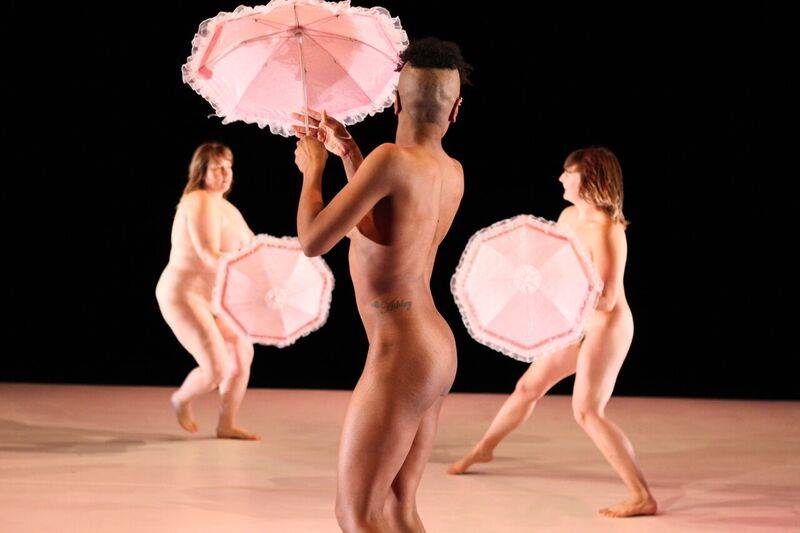

The early twenty-first century has witnessed a dramatic surge of interest within the visual art world in performance-based works, sparked not only by the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of art today but also by larger social shifts toward a digital culture (and an associated diminished attachment to the physical) and a heightened societal valuation of the experiential. Yet despite the acceptance of performance as an essential form of contemporary art practice, museums continue to grapple with the inherent questions and contradictions of collecting it. How does an institution acquire, preserve, and display work that was built for real time and space, that essentially disappears after its time has expired? The best-practice jury on this remains out. Performance-collecting strategies are currently all over the map: they include acquiring documents (photography, video, film, etc.); securing artists’ instructions for execution (primarily through future “reperformance”); and collecting the associated physical elements (remnants) of what is left in the wake of the live performance experience—sets, scripts, costumes, props, videos, scores, and designs for lighting or sound.

Examples worth considering are the strategies of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York; Tate Modern, London; and my institution, the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. In 2008 MoMA established its Media and Performance Department and began to aggressively expand its performance collection; an early acquisition was Tino Sehgal’s Kiss (2003). MoMA consciously prioritized work that could fit well in its museum galleries, and it defined ownership as the holding rights to reperform the works it purchased, works that ideally came with a score or set of instructions that would facilitate reperformance. MoMA attempts to capture video documentation of artists describing in detail how they want the works to be (re)performed in the future.

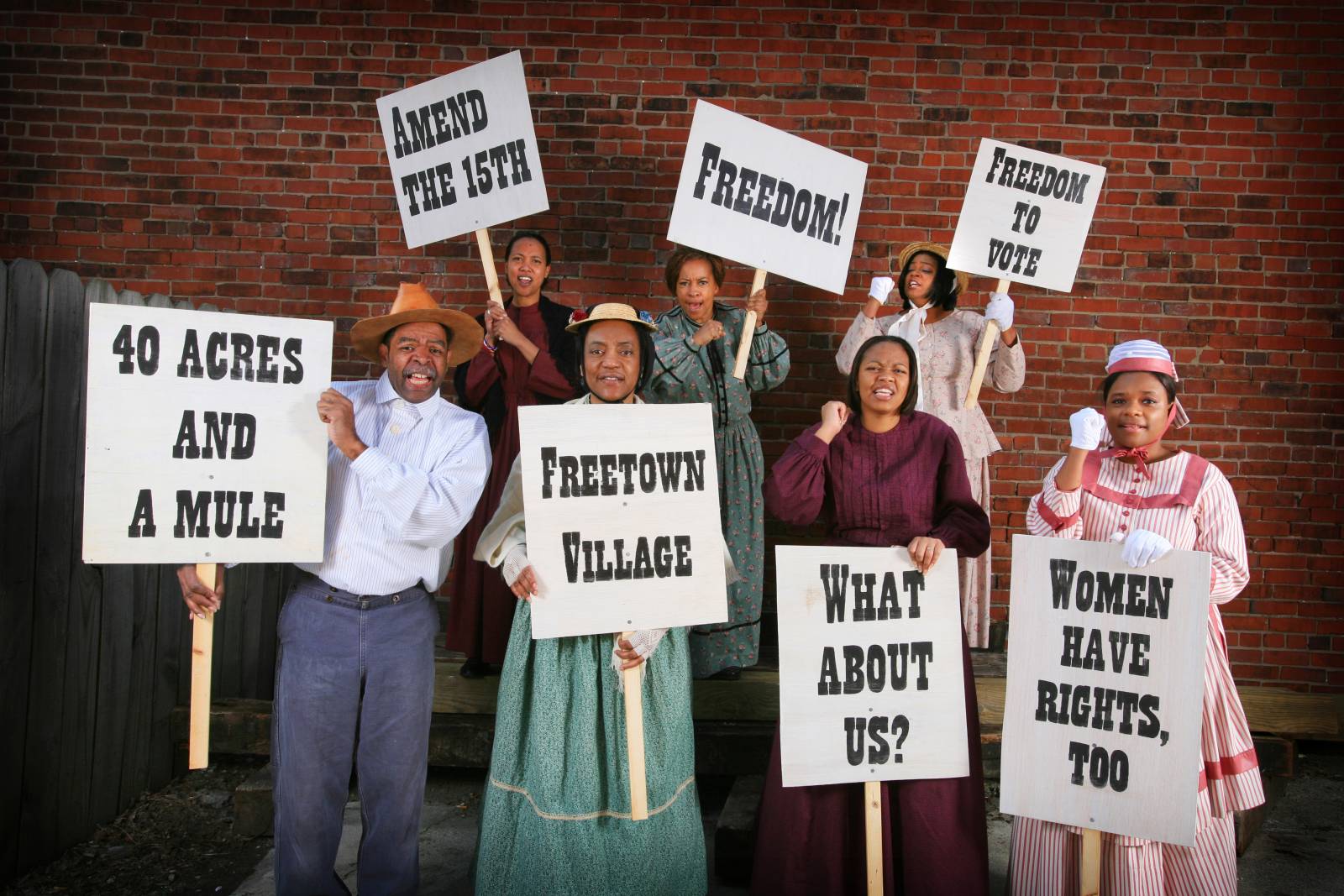

In the United Kingdom, documentation and scholarship of “live art” have had a longer history. Yet the act of collecting performance work remains equally unresolved. In 2012 Tate Modern launched a research initiative called Collecting the Performative, rooted in the idea that “traditional approaches to conservation and . . . management of collections—based on the assumption that a museum object is materially bound and fixed—need to change,” yet readily acknowledging that the very essence of performance “is at odds with long-established systems and processes for managing art as a material object.” The Tate initiative actually looks to how “dance, theatre and activism practice” document and attempt to conserve their histories to see if some answers might lie there.

As an art center (as opposed to a museum), one with a long-established Performing Arts program that supports contemporary dance, experimental theater, and new music of many stripes as well as interdisciplinary and performance art, the Walker attempts to approach the different histories/orientations of the performing disciplines it serves in ways fairly distinct from the way it approaches the visual art it collects. Thus, it has long “commissioned” rather than collected live art; this means that the Walker has financially invested up front in these works and attempts to retain some documentation for, without claiming any ownership of, the nearly three hundred pieces in its commission history. While the Walker has chosen to ensure that artists retain the actual rights to and ownership of their own work, the institution still sees its commissions as a type of collection. Yet it is also clear that this “collection” really behaves more like an activated archive whose relationship to the Walker’s Visual Art Collection (once called its permanent collection) is appropriately being questioned.

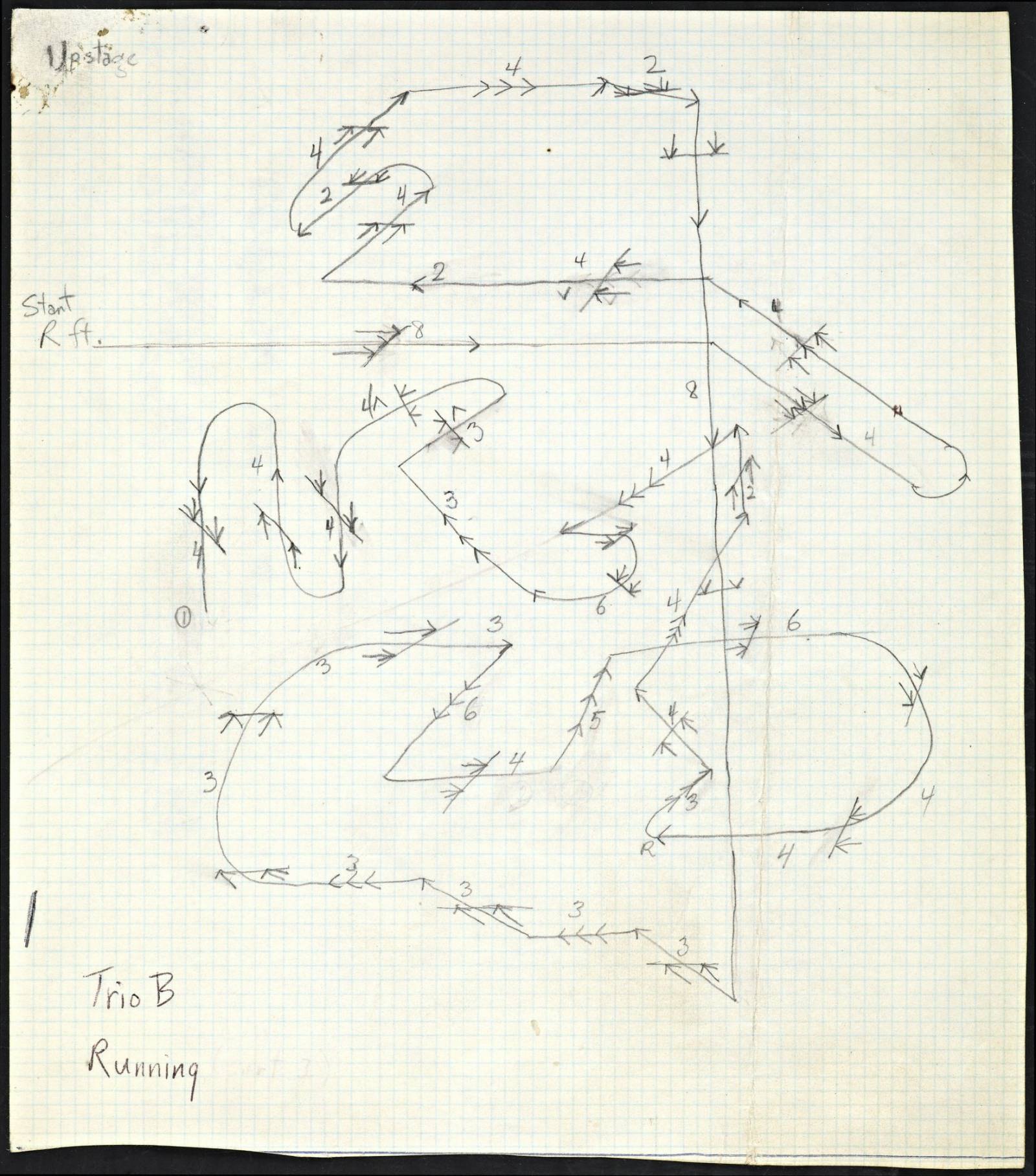

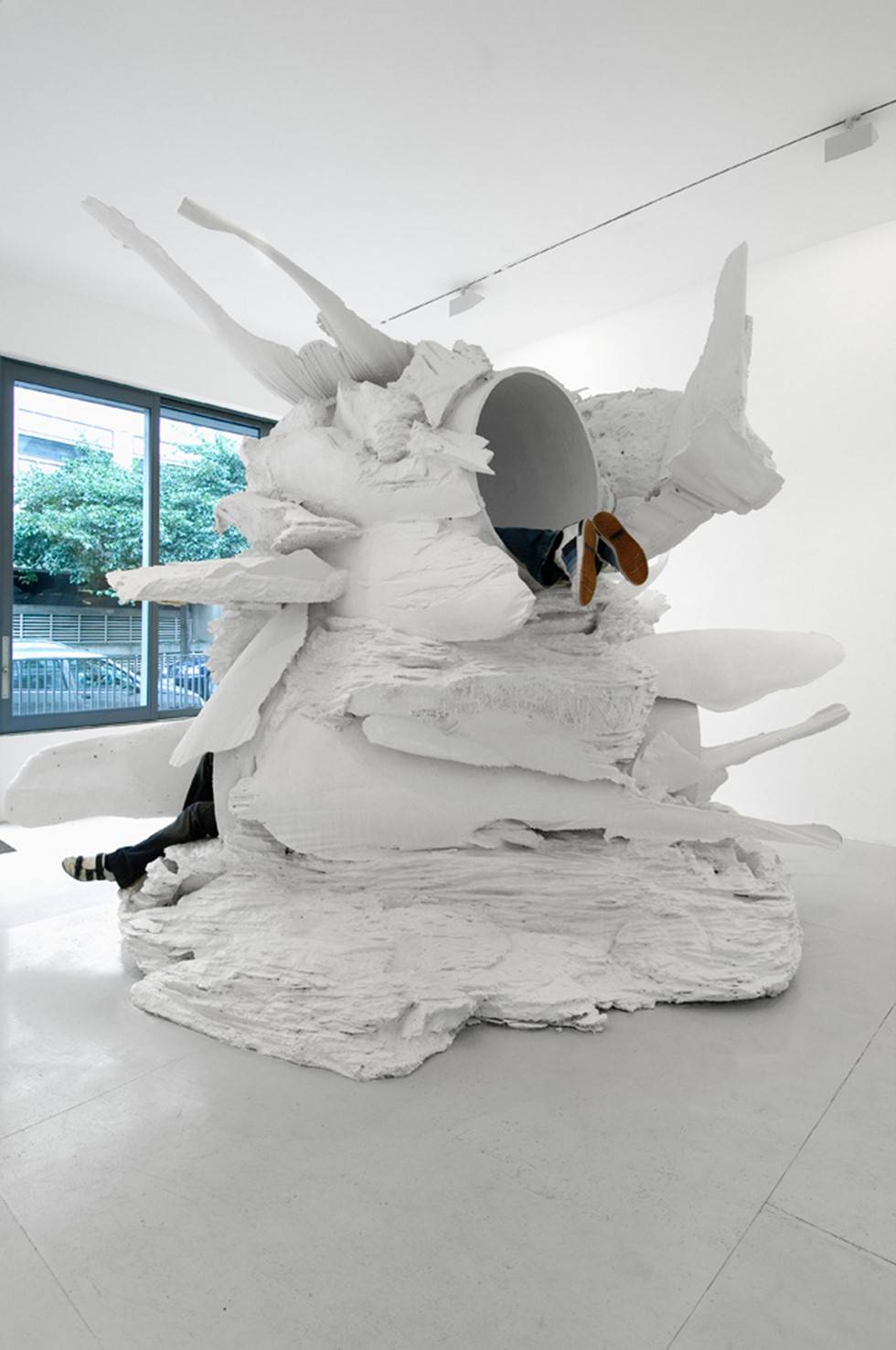

In addition to commissioning, the Walker sometimes acquires performing art–related objects for its Visual Art Collection as well, a practice that began with the purchase of Jasper Johns’s Walkaround Time (1968; based on Duchamp’s Large Glass) in 2000. At the time Johns himself said he didn’t consider the piece “a work of art” but rather “just” a stage set (for a Merce Cunningham dance of the same name). Since then the Walker has gone on to purchase physical elements of works by Meredith Monk, Ralph Lemon, and in 2011, the entire set/prop/costume archive of the Cunningham Dance Company, comprising more than four thousand objects. In this latter realm, the Walker has chosen the strategy of acquiring physical elements (often created by leading visual artists) of live performances rather than purchasing “the performance work itself” for future reperformance. It is hoped that these objects, in consort with the ongoing commissioning “collection,” will combine to tell a rich story.

In addition to these two approaches, the Walker is considering a somewhat unorthodox third stream: on occasion, to fully “collect” a performance without claiming exclusive ownership. Some artists (the interdisciplinary artist Ralph Lemon comes to mind) are deeply exploring what it might mean for an institution to “acquire” but (unlike in Sehgal's case) not exclusively own a work or an edition of a work. In this instance, “ownership” would not consist of exclusive rights to show, reperform, or buy or sell these rights but would instead relate to the Walker acquiring its own experience of the work it “owned,” its own documentation, its own collective and individual memories, recorded and not. While admittedly a somewhat subversive (or anti-market) gesture, it also serves as an effort to raise the value of the performance moment, the temporal performed experience, perhaps through oral histories of participants, collaborators, and viewers; it would chart process beyond the norms of standard documentation, for example, undertaking the intellectual and emotional mapping of the performance creation and experience by artists and viewers alike. Can an institution divorce the notion of “ownership” from exclusivity? Perhaps it is time to attempt to transform the lexicon of the museum, further challenging the disciplinary lines that continue to feel rigid, as well as examining the distinctions of value that populate the visual and performing art worlds in such different ways.

It is an intriguing moment, resting on more questions than answers: How can a set of memories, a collective experience, be preserved? Can an ephemeral work live on as a respected part of a museum’s “holdings” after the last person who saw it is gone but without material items or standard documentation from that live artwork? What are the various means by which an institution or, for that matter, a community might continue “to hold” a performance work? These questions and others will continue to pervade future efforts to “collect” performance.

For Further Reference

Yves Klein, Suaire de Mondo Cane (Mondo Cane Shroud), 1961.

Kazuo Shiraga, Untitled, 1959.

Jasper Johns, Walkaround Time, Merce Cunningham Dance Company, 1968.

Robert Rauschenberg, costumes and cotton canvas drop for Summerspace, Merce Cunningham Dance Company, 1958.

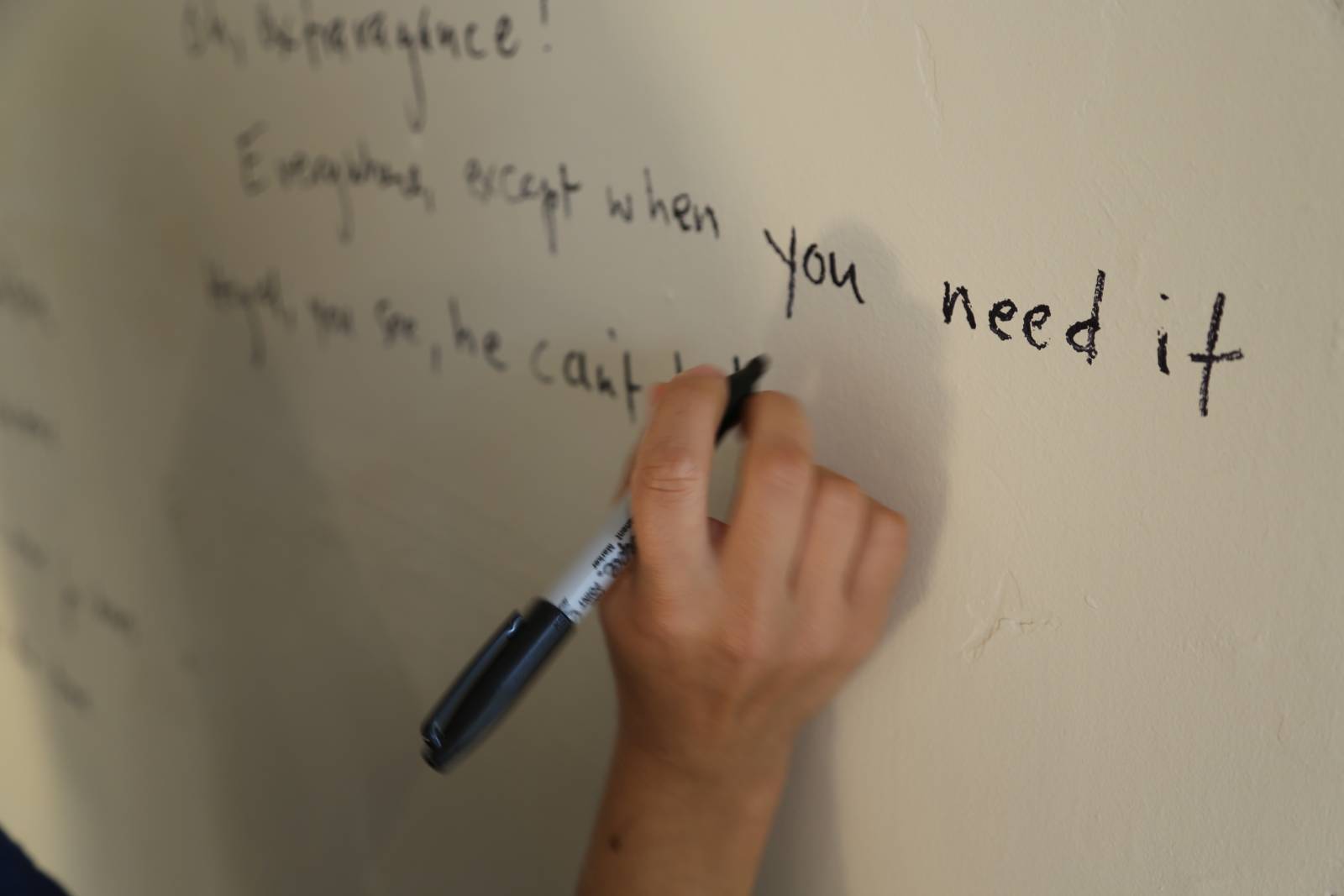

Trisha Brown, It’s a Draw/Live Feed, 2002.

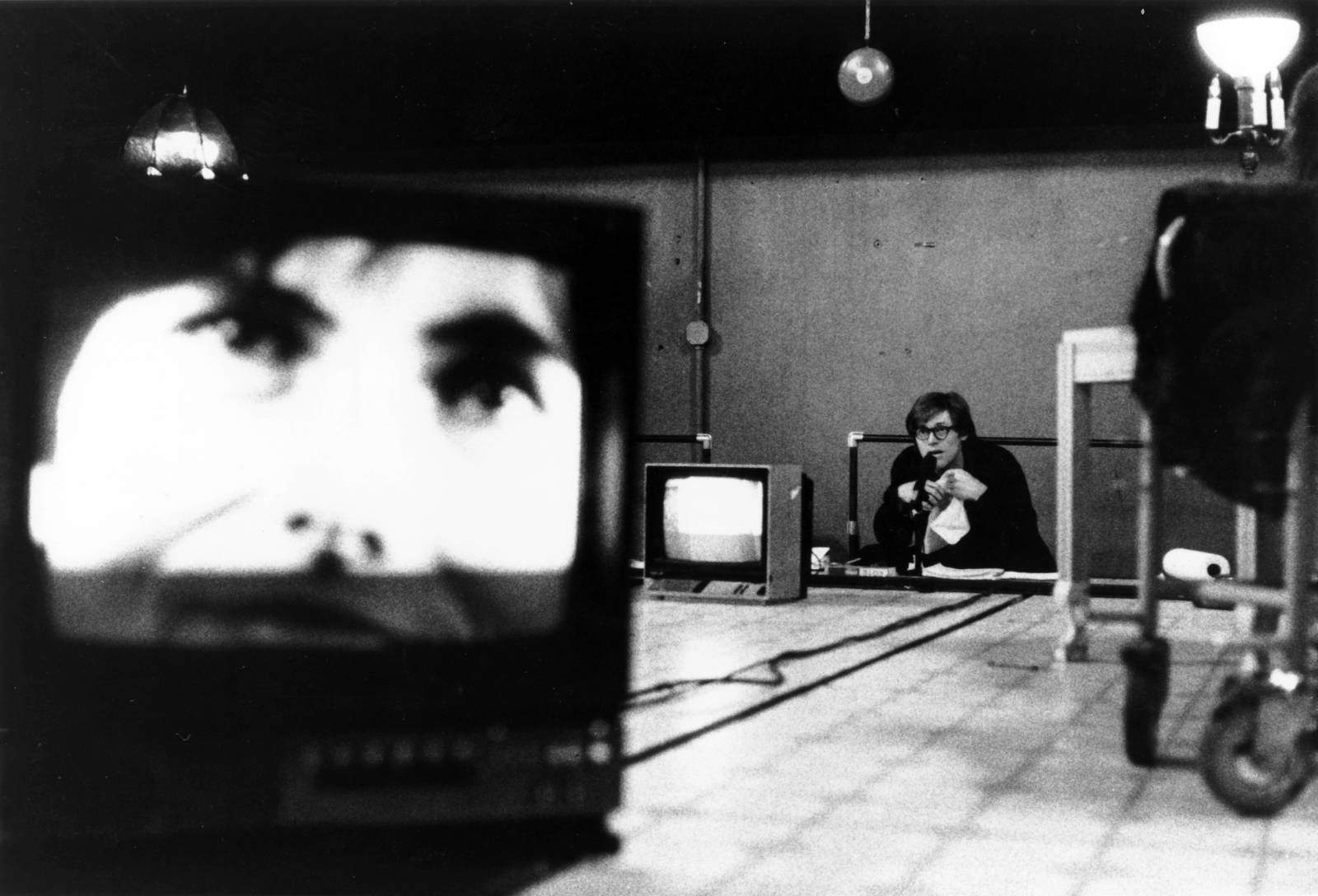

Adrian Piper, The Mythic Being; I/You (Her), 1974.

Meredith Monk, 16 Millimeter Earrings, premiered 1966, Judson Memorial Church.

Ralph Lemon with Jim Findlay, Meditation, 2010.

Ralph Lemon, Scaffold Room, 2014. Commissioned by the Walker Art Center.