Yvonne Rainer (born 1934, San Francisco) is a dancer, choreographer, and filmmaker whose deeply political and feminist work has challenged ideological and formal conventions for more than five decades. A founding member of the Judson Dance Theater and the improvisation group Grand Union, Rainer was a key figure of 1960s and ’70s minimalist and postmodern dance, incorporating everyday movements and sounds and rejecting traditional narratives in favor of tasks, patterns, and game-based structures. In the mid-’70s she began making experimental films, returning to choreography only in 2000. Her most recent performance, The Concept of Dust, or How do you look when there’s nothing left to move?, was commissioned by Performa and the Getty Research Institute (which maintains her archive) and premiered at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

IToP

With what kinds of artists or art professionals are you most comfortable conversing? On the other hand, whose language is most unfamiliar or disabling to you?

YR

The language of drama critics and playwrights always reminds me of what Anthony Hopkins supposedly said to a theater actor: “Still yelling at night?” I used to attend a lot of plays, but the naturalistic kind of theater that directors engage with no longer interests me. When I see well-meaning and -crafted naturalistic performances in movies I can take it—I can lose myself and identify with the characters—but not in theater. I was raised with Beckett and Ionesco and to a certain extent Brecht, all of whom intentionally challenged the audience’s “suspension of disbelief.” Perhaps it is a certain literal-mindedness that I inherited from these theater rebels, compounded by Minimalism in the visual arts, that fueled my resistance to psychologically infused dialogue and coherent narrative in theater. I am more comfortable with the language of dance, its materiality and immediacy. As for film language, the techniques of conventional film narrative already immerse the viewer in the diegesis, dispensing with any effort at “suspension.”

IToP

Let’s talk for a moment specifically about language in terms of words—how meanings might drift or shift or have different values when transported from one context to another. Even the word performance means something different to people working in different fields.

YR

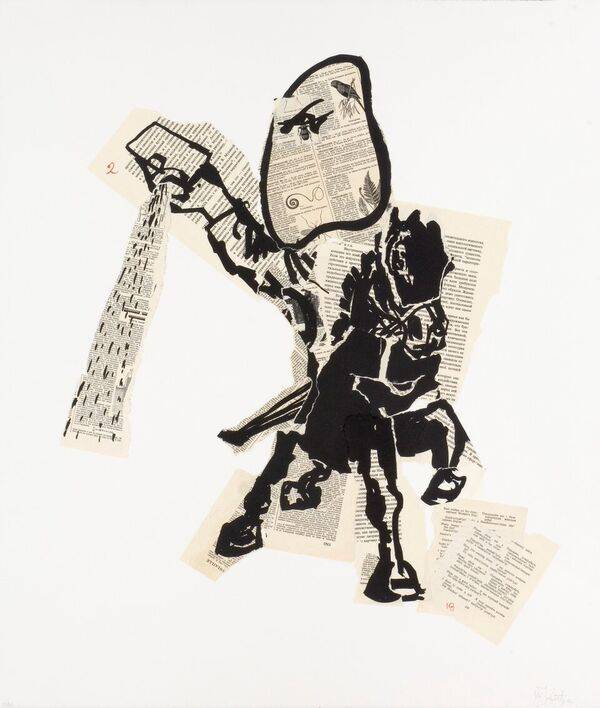

Sure, both the words performance and language mean different things in theater and in dance. I should point out that I use a lot of language these days. It is a distantiation device. I don’t own what I say; I am reading other people’s words, and I give them to my dancers. It’s a parallel strategy to the dance moves, and it’s also quite disconnected.

IToP

From where are you sourcing your language?

YR

Everywhere, from philosophy to literary criticism to whatever I’m reading, from bad jokes to the wall inscriptions in the Islamic wing of the Metropolitan Museum. I’m all over the place.

IToP

Are there any realms of language from which you wouldn’t borrow?

YR

Naturalistic dialogue.

IToP

Understood. As for interdisciplinary literacy, what does it mean for an artist to be “literate” in the disciplines he/she engages? What are the possible benefits of being “illiterate” within certain disciplines?

YR

Dance in museums brings up some of these issues today. Too many art historians do not know their dance history. When I switched from dance to film, in 1972, I already had literacy in film. I was following the New American Cinema and European cinema in the 1950s and ’60s. I was going to foreign films from the time I was a young child.

IToP

When entering that realm, then, you did not feel handicapped—for better or worse?

YR

Well, I certainly was handicapped technically, and even after making seven films, I would say I’m a techno dummy of the camera and lighting. I depended on people with that knowledge, though, of course, there was an ongoing conversation about what I wanted, what I imagined, and it was the job of the people I worked with to realize what came out of my head. I’ve always admired my filmmaker peers who do their own camera work. Eventually, I became an expert in editing on the Steenbeck. I learned that as I went along.

IToP

Was there ever a time when your work either suffered or benefited from a miscommunication, when the assumption of your intent was misconstrued as a result of moving from one artistic context to another?

YR

In the 1960s a dance critic wrote that “someday there will be a real murder in one of Yvonne Rainer’s dances.” When I made the transition to film, some filmmakers complained that I had “no visual sense.” Others said my films had “no narrative drive.” It’s odd how such barbs stick while the many favorable and sympathetic observations fade.

IToP

Did those criticisms impact the way you thought about your work?

YR

No, it’s all part of a day’s work. You know, some like what you do and some don’t. As for visual sense, there was something about filmmaking that I had a very acute visual sense for, and that was framing the way the film framed. That’s a language all by itself. And narrative drive? I deliberately made disjunctive narratives. That was what I was interested in. People who didn’t see this in terms of a coherent narrative, they were out of luck. It really had to do with the division between traditional and experimental narrative. I never expected what I did to attract a big audience. I wasn’t even after the kind of audience that goes to the art cinema, let alone the Multiplex.

IToP

What words do you find most resonant in the contemporary art and performance world? What words most confuse or annoy you?

YR

In the annoyance department is iteration. All of a sudden everyone’s using it, and all it means is learning through repetition, another version of something. It seems pretentious to me. Another annoyance is the word immersion. It refers to a relation to the audience that I have no interest in whatsoever, and that is audience participation. I expect the audience to stay in their seats. When you go to the circus for the high-wire act and the trapeze, they ask you to be very quiet and attentive and not make noise. I ask for that kind of concentration in front of my work. I expect it. It’s not supposed to be an immersive experience.

As for the language that I find most resonant: in dealing with my work, I try to be purely descriptive and avoid spiritual, mystical, or socially progressive interpretations. Sometimes, however, as when one is applying for money, one must make claims for a “higher” purpose.

IToP

What you were saying about audience participation ties back, in some respects, to the concept of distantiation you were talking about earlier.

YR

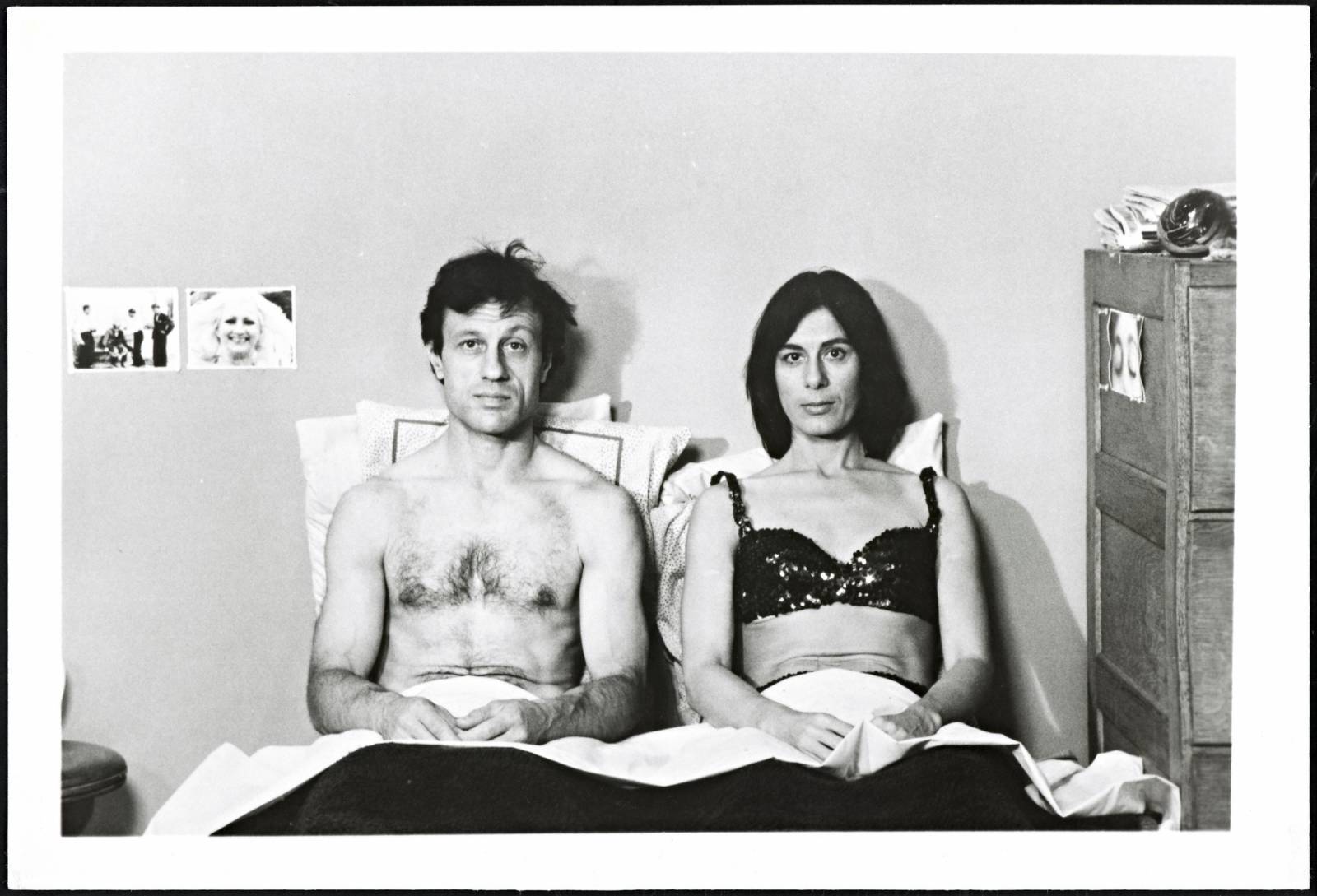

In my later filmmaking, I used actors who portrayed characters, but I used them to absorb and engage the audience only to then disrupt their absorption. An example: the audience is watching a sequence with a voiceover, and all of a sudden the voiceover becomes an intertitle that they have to read. I was pulling them in but ultimately pushing them away.

IToP

You have great facility in a number of mediums. How do you think about the terms interdisciplinary or intermedial within the context of performance—do they have a specific meaning and value for you?

YR

I’m not sure how broadly you’re defining interdisciplinary. I made a version of Rite of Spring where in the middle of it I had a group of fifty people storm the stage in protest and then leave. I also had signs descend from the rafters with various words on them referring to the history of the dance. That was very elaborate; I worked with a set designer, and it was in a theater, on a proscenium stage.

IToP

Would it be safe to say that those were theatrical engagements?

YR

Theatrical, yes. But I no longer regard my work, at least in its current phase, as interdisciplinary. It contains movement derived from various sources, the use of trained dancers, live readings or recitations, and occasionally props, but none of that would justify its characterization as interdisciplinary or intermedial. I guess what I’m doing now is simpler and more intimate; it’s complicated by the use of the texts, but that’s as far as it goes.

IToP

Is the move away from using theatrical conventions prompted by either a comfort or discomfort with engaging this other discipline?

YR

No, it was practical. When you tour, especially in Europe, you don’t want to lug a lot of stuff around. I don’t have that kind of money or economic support. So, the simpler the better, you know? We carry what we need on our backs. When Rauschenberg was set designer for Cunningham, they’d go into a theater and into the wardrobe or prop department and gather up whatever they found there.

IToP

Does the ability to draw readily upon various disciplines better facilitate the delivery of content and ideas for you? Does it allow for greater play or freedom in the creation of your work? Are certain kinds of content or ideas more easily explored in certain mediums?

YR

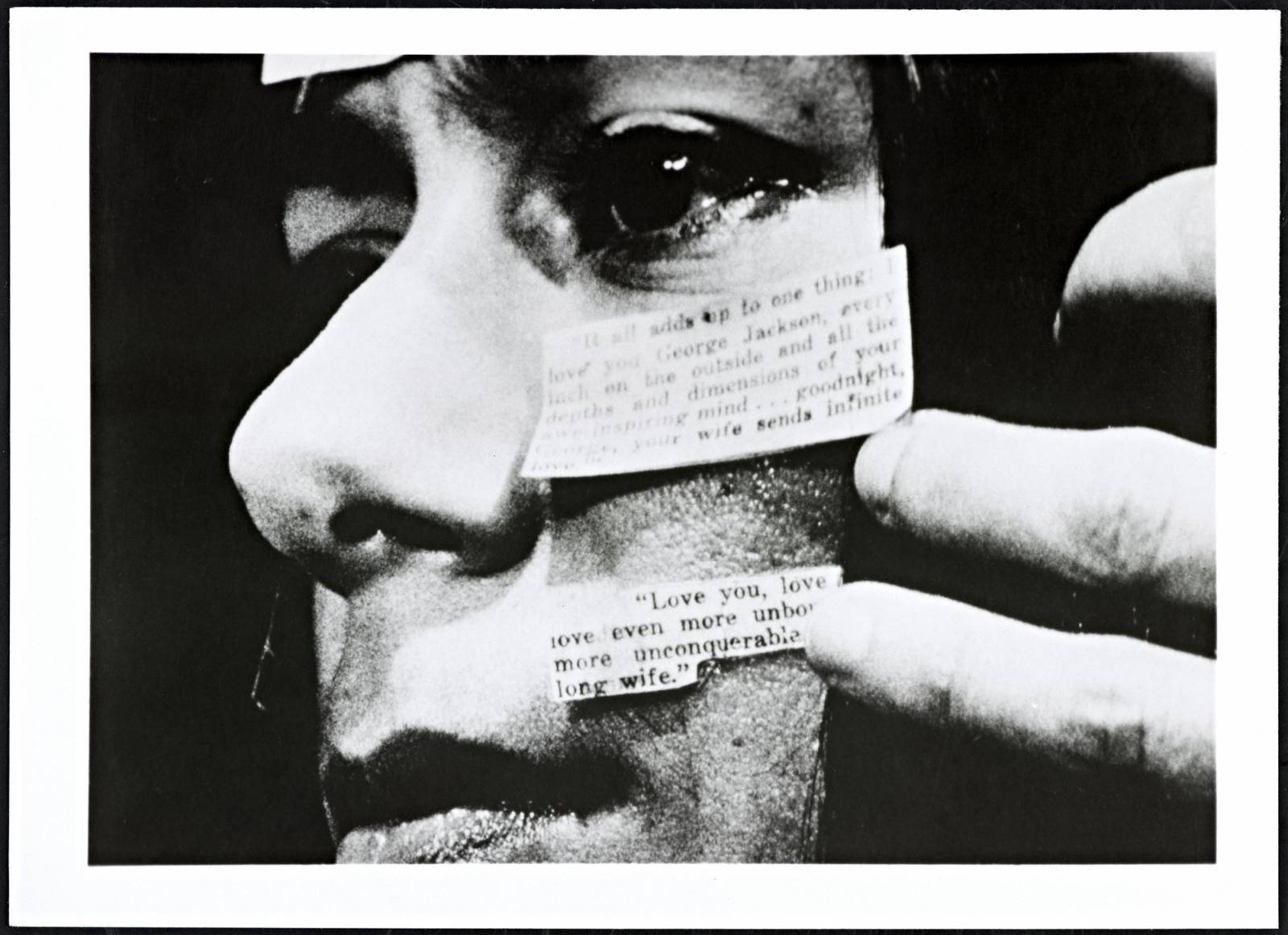

I turned to film in 1972 because at the time film seemed more appropriate for dealing with the specifics of political and social issues. I didn’t make metaphorical or socially referential movement. If the dances could be called “political,” such a term was relevant within what seemed to me to be the narrow confines of dance history. Film was the medium that could accommodate my evolving feminism and a farther-ranging politics.

IToP

Why was that? Was it the discourse around film or actually the nature of the medium?

YR

It was the nature of film itself. It could accommodate language as intertitle, as subtitle, as synched sound, as voiceover, and verbal language could be integrated with visual language. I didn’t feel I could do that in dance. I didn’t make a narrative, metaphorical kind of movement. I didn’t tell stories with the body. Film offered a much wider range of possibilities for content—in addition to the traditional modes of acting and characterization. Coming back to dance later, I realized that verbal language could now carry the weight of social commentary independent of the dance movement I made. The two parallel trajectories could coexist.

IToP

Were you enabled to bring language into dance because dance had changed, or because the audience’s expectations were different from those of the early 1970s?

YR

No, it has nothing to do with audience expectations. I just have two totally different interests. I’ve always been interested in the juxtaposition of things that don’t match. And I make this demand on the audience that they follow the physical aspect of the piece, the movement, and at the same time they can listen to material that the movement does not relate to. It’s all in this tradition, a postmodern tradition, of radical juxtaposition, to use Susan Sontag’s term.

IToP

Are certain contexts more enabling for you?

YR

That’s hard to say. The most appreciative audiences for my choreography come from visual art, academia, dance, poetry, probably not film as much. The biggest hurdles for choreographers today—and that includes me at age eighty—have to do with space and time and the availability of dancers for daily work sessions. Unless you have institutionalized yourself with a stable “company,” board of trustees, fundraiser, manager, et cetera, the opportunities for performing are few and far between. In my youth, the “enabling context” for making work was the gymnasium of Judson Church, where we could fool around on a regular basis (free of charge!) and not present formal shows until we were ready. There are all too few opportunities for this kind of communality today, for obvious reasons.

IToP

When is your work constrained by the frame of “dance” or “the museum,” and when is it enabled by those frames?

YR

The people who come to see my work know what to expect. I don’t think about framing my work for a specific audience, let’s put it that way. I don’t think I’ve ever felt constrained by anticipating a particular audience. I mean, sometimes it’s gotten me into trouble. In my early days, when I was beginning to make dances, I had the support of my peers. I think I lucked out. I came at a certain time when New York was boiling with all kinds of rebellion. We expected to make waves and yes, I can remember a particular performance I shared with Steve Paxton and David Gordon and people walked out. At Judson Church, to get out you had to be brave because you had to walk across the performing area. So, yes, there were occasions like that—that particular one was a downer. The response in terms of reviews was always invigorating, both the ups and the downs, the negative and the positive. I would say that neither the audience nor the critical response affected me in terms of what I wanted to do. I was affected more by what I saw in the field, what my contemporaries were doing, what was happening in my immediate environs.

As for the frame of the museum, I think of the constraints as being related to a lack of respect for artists, their needs, and their contributions. Museums, like the Whitney and MoMA, are finally building theatrical spaces into their architectural expansions. If they plan to show dance, they know that things have got to change. Sprung floors? Dressing rooms and showers? Far be it for us modest, grateful dancers to bite the hand that feeds us, however insubstantially. I never thought about these things when I danced at the Whitney in the early 1970s. My frustrations must be age-related.

I had a meeting today with several curators at MoMA, during which we discussed my upcoming series of performances. On leaving the office and walking down a corridor I caught sight of a photo of Steve Paxton performing in the MoMA garden in the late 1960s or early ’70s. There he was all askew while doing a bravura headstand. Two items caught my attention. One, his head was making contact with the stone surface of the outdoor space, and two, he was not identified in the caption beside the photo.

IToP

You work collaboratively in some of your performance work. How do you like to name your role in a collaboration?

YR

I would rather not call interacting with and being influenced by my dancers “collaboration.” Or working with a set or costume designer. Grand Union was a collaboration, the group that came out of one of my last dances in the early 1960s, Continuous Project—Altered Daily. It evolved into a situation where everyone brought in their own materials and the resultant performance was, yes, a collaborative event. We didn’t rehearse or work together beforehand, we just met at a certain time and place and related to each other, interacted in the performance. That is, I think, the extent of my collaboration. What I do now, I’m certainly the final authority, even when I ask the dancers to contribute. My current dance, The Concept of Dust, or How do you look when there’s nothing left to move, has an indeterminate structure; the dancers have the option to initiate and perform material at their discretion throughout the evening. Does that constitute collaboration? For egotistical reasons I prefer to say flatly that I don’t collaborate.

IToP

Can you talk about the role of scores in your practice?

YR

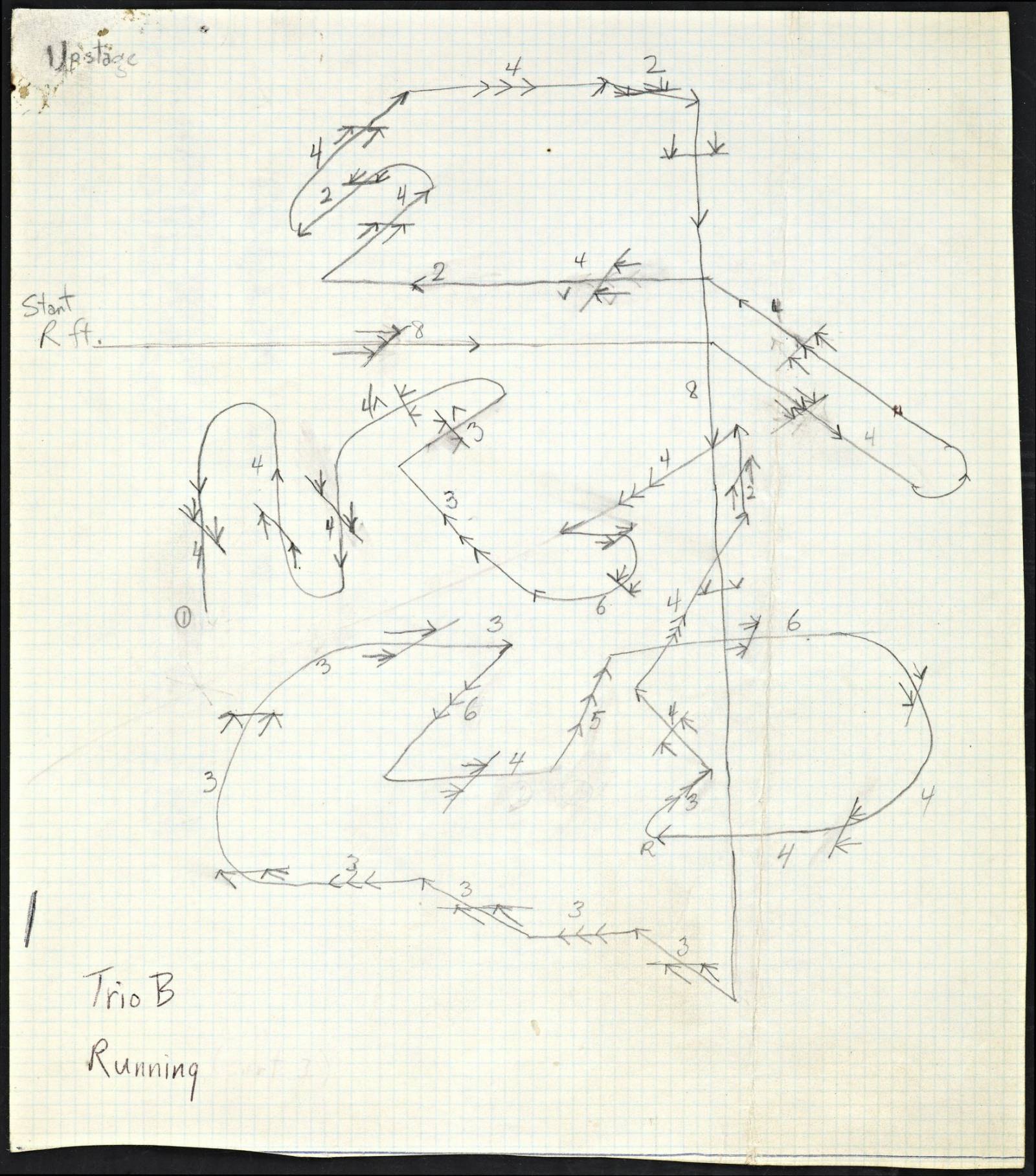

I’ve made all kinds of scores, either lists of materials or rules about how they were to be used, and a few graphic scores. I know Lucinda Childs’s graphic scores are the basis of her work, and I’ve made a few of those, especially in large group pieces, indicating floor patterns and sequence.

IToP

Do you see these scores as providing a means of working out the dances, or are they for use later in the reconstruction of the work?

YR

The score in some cases was made before rehearsals, so it was something to be borrowed, something meant to produce the dance. There are also all these essays I wrote after making the dances, which would help me clarify what they’re about.

IToP

What would be the role of the score in a reperformance or reconstruction?

YR

It’s essential. That’s how some of my dances have survived. In some cases, the scores are indecipherable; in other cases, they will produce the dance accurately.

IToP

Do you have a position on the reconstruction of your work?

YR

I am so undecided about such matters that maybe the best way to answer the question is to refer to what, for better or worse, is still perceived as my “signature” dance, Trio A. Trio A is transmitted by five dancers authorized by me to teach it. I forbid Trio A to be learned from the video documentation of my own (flawed) execution of it from 1978. No one can teach or perform it without my permission. Those who learn it from the authorized transmitters must sign waivers. As for my evening-length dances, very little survives from 1960 to 1975: the solos Three Satie Spoons, Three Seascapes, and Talking Solos and group works We Shall Run, Diagonal, and Chair-Pillow. These have been performed by members of my current group and videotaped on various occasions. Since 2000, when I returned to dance, I have tried to have everything I do videotaped.

IToP

Is the videotape purely documentation?

YR

Yes, in most cases. But regarding Trio A, there was one camera, and the floor patterns are very specific, and you cannot tell how much space is being covered or what the exact direction or trajectory of a given traveling movement is in the space. You can’t reconstruct that dance from the video. And there’s only one video of it.

IToP

Are you setting up some means of ensuring that there are dancers always trained to reperform your work?

YR

No, I’m not. With Trio A, it will be up to the five transmitters I’ve trained. They will decide when they’re reaching a point where they can teach it to others. In my first book, titled Work in 1961–73, I give people permission to use the notes it contains to remake the dances. At the time that I wrote the notes, I thought they were elaborate and clear, but a lot of it I can’t decipher now. I give permission and ask to be credited in the program notes.

IToP

You are a teacher and mentor to many artists. What kinds of skills, ideas, and dispositions do you wish for your students and emerging artists? And for the institutions that might one day support their work?

YR

The artists need lots of courage and tenacity. The curators need sensitivity as well as courage and tenacity. The institutions need to listen.

IToP

In your now well-known “No Manifesto” from 1965, you rejected notions of spectacle and virtuosity. What is your thinking about such words now, along with counterterms such as the everyday or amateur?

YR

I revised my “No Manifesto” in 2008.

A MANIFESTO RECONSIDERED (Yvonne Rainer, Serpentine Gallery, London 2008)

1965 [2008]

No to spectacle [Avoid if at all possible.]

No to virtuosity [Acceptable in limited quantity.]

No to transformations and magic and make-believe [Magic is out; the other two are sometimes tolerable.]

No to the glamour and transcendence of the star image [Acceptable only as quotation.]

No to the heroic [Dancers are ipso facto heroic.]

No to the anti-heroic [Don’t agree with that one.]

No to trash imagery [Don’t understand that one.]

No to involvement of performer or spectator [Spectators: stay in your seats.]

No to style [Style is unavoidable.]

No to camp [A little goes a long way.]

No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer [Unavoidable.]

No to eccentricity [If you mean “unpredictability,” that’s the name of the game.]

No to moving or being moved [Unavoidable.]