Tim Griffin is executive director and chief curator of the Kitchen, New York, where he has organized both exhibitions of visual art and performances by choreographers and musicians, including Chantal Akerman, Aki Sasamoto, Morton Subotnick, and Danh Vo. From 2003 to 2010, Griffin was editor in chief of Artforum, where he published special issues on the legacies of minimalism and land art; contemporary notions of performance; art and its markets; the philosophy of Jacques Rancière; and the state of the museum. He has a MFA in poetry from Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts and has written extensively on artists including Wade Guyton, Paul Sietsema, Elad Lassry, and Taryn Simon, among others. In 2015, he was awarded the insignia of chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters.

IToP

With what kinds of artists or art professionals are you most comfortable conversing? Who speaks your language?

TG

I’m probably most excited to speak about art with people who approach work—and one’s own position, or subjectivity, whether the artist’s or the audience’s—as it exists within a given cultural, social, and institutional context. Or, maybe better, within such a context whose historical course is nevertheless subtly but substantively changing.

Things signify and function differently within the syntaxes of different situations; this we’ve known. And, moreover, one should be wary of “things that go without saying.” (In this regard, ostensibly progressive moves in art can be, in fact, among the most conservative, and vice versa.) But when I’m working with artists or art professionals, my hope is to take into consideration not only the underlying assumptions along these various axes of context, but also the potential ambiguity. The ambiguity of one’s own place today, of the positing—and positioning—of the audience, and of the ideation of a public. Working within a smaller institution with both a deep history and access to theater and gallery spaces with distinct protocols offers artists and curators a unique opportunity to engage with these broader questions.

As for those who speak this language . . . I think many people do. The questions of what an art institution is; of what an audience or public is; of how disciplinarity and modes of aesthetic address correlate with politics and political structures; of how identity operates and is received: all these questions are on many people’s minds. The funny thing is how the institutions themselves—which we so desperately need in order to give a language to such efforts, and ways of life—have not yet adjusted to these different cultural conditions. The structures for presenting art can seem a shadow land. One story of the past decade and a half is that of institutions seeming to belong to another time—in a way distinct from discussions around postmodernism—and of needing to adjust to a new one. The literal juxtaposition of disciplines and contrasting display models, and of audience, at The Kitchen lends itself to engaging such complex issues.

IToP

So many people are speaking this language, but institutions have not yet adjusted themselves? Are you making adjustments at The Kitchen—in the work you present and in your processes?

TG

I don’t think these questions necessarily must be addressed explicitly in a work. They’re going to be there regardless. But I guess I begin any collaboration—especially any collaboration at The Kitchen—against the backdrop of that particular conversation, and we seek to put the apparatus and protocols of context at the artist’s disposal. Sometimes this takes a concrete shape. For example, when an artist is given the opportunity to deploy a theatrical lighting grid in the gallery: What happens when such lighting gets introduced in a gallery as an interjection—as a kind of content that both disrupts and adds, or offers the operation of interjection as an object? How the audience orients itself with respect to viewership, and even temporality, changes. On other occasions, the conversation is more abstract, just giving an artist a sense of the history and discursive terrain of this particular place. But I suppose the phrasing of your question also makes me consider the value of featuring work that goes against this grain in this context, to keep the forces of petrification at bay—or to allow different work, even mass-media work, to be encountered freshly in this register.

IToP

Do you talk with each other about “multidisciplinarity,” the value of crossing boundaries among art, dance, performance?

TG

It’s not the word I choose. I find myself using “inter” rather than “multi-,” which suggests an interlocking network—or more precisely, a group of disciplines with specific histories juxtaposed, often with seams showing—rather than just a plethora of things assembled. Interdisciplinarity acknowledges that there are differences that persist in the exchange.

IToP

Can you give some examples of people whose work crosses and “interlocks” in ways that are exciting for you at The Kitchen right now?

TG

Maybe a better thing for me to say is that there is no artist who walks into this space who doesn’t anticipate having this kind of flickering conversation. We have the conversation about what walking into this particular space means. And we put that architecture, that history, and that infrastructure into the hands of the artist so he or she can make use of the space in any way. They don’t have to make use of everything, but that conversation functions as a kind of backdrop to the collaboration. And it is part of the assumption of what it means to work here.

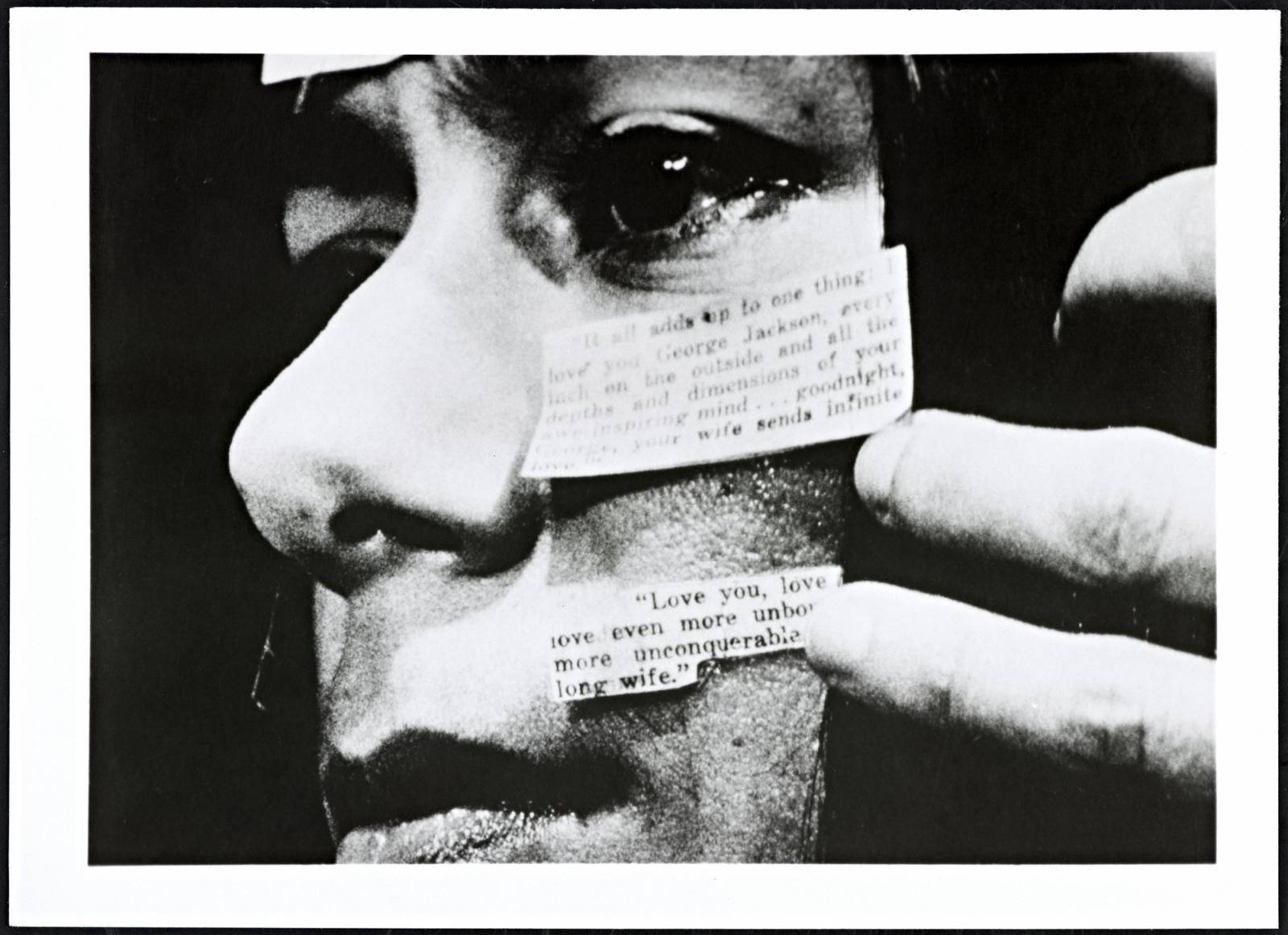

That said, I was very lucky to work recently with Ralph Lemon, who took over the entire building and allowed a kind of ambiguity to pervade the spaces—whether between lecture and performance, installation and stage, or live performance and embodied history. One was continually reconsidering one’s relation to the work, and to the apparatus of its presentation. I think of an anecdote from his earlier work, in which he compares a Bruce Nauman piece using performance and architecture to contemporaneous civil rights actions by and around Martin Luther King. How one behaves in space, and how one stands in dialogue with it—and with its history—is a necessarily political endeavor. And the body, as well as its movements or choreography, both social and artistic, contain histories.

IToP

Before you accepted your current position at The Kitchen, you were the editor in chief of Artforum. Can you say something about what it meant to move from one venue to the other?

TG

I always took editing at Artforum as a kind of curatorial practice, with juxtapositions creating correspondences in a Baudelairean sense. It was even somewhat spatial: At the start there, I compared the construction of issues to Genet’s interest in vase-makers who developed vessels around single flaws from which the entire structure would emerge. But it’s one thing to do something like this in writing—with such “species of spaces,” to borrow a phrase—and another to work with people with different histories in disciplines. Even understandings of context are highly specific according to medium. At least that was my experience some five years ago. And then, of course, there is the small matter of operations—when the temporality of a theater is inserted into a gallery setting, for example—prompting the creation of novel and idiosyncratic budgetary templates.

Maybe the motivation for the move itself is most interesting to consider now, with a little distance. The move, for me, meant realizing that the conditions of production and reception were changing, whether in regard to pop-cultural influences on art or understandings of representation. And then there was the question of positioning—literal and figurative—the audience, which bent back as a model to the question of the shifting structure of organized society generally. So then the obvious point of transition is that now I’m dealing with physical bodies in a space. So it’s about realizing that vision in actuality, in a generative way. This is an unfinished project.

IToP

There seems to be a difference between literary editing and performance curating.

TG

The analogy is meaningful, but of course there are huge gaps, especially regarding the understanding and use of time. Coming here, I had to understand time, what that really means—how that interfaces with how people use their time, and with how they interface in turn with each other, and so on.

IToP

Do you think that the audience for The Kitchen and the readers of Artforum are the same?

TG

Only in part. Even within The Kitchen itself, the audience is not necessarily the same from show to show: often, music audiences see music, dance audiences see dance, and art audiences see art. There’s a kind of atomization. We try to bring these different audiences and programs together while showing the seams, and, hopefully, allowing for a circulation and use of different models.

But, to speak to your question, what’s perhaps most important are epochal gaps. When I was at Artforum, we put a choreographer on the cover for the first time. This is a little crazy to consider. The discussion of performance and dance within the visual art context was just arriving, and much of what I sought to pursue—while honoring the work of the artists—was to seek institutional and historical distinctions between performance as it existed some forty years before and performance as it was emerging in such a context during our own day. This was at once novel and against the grain, I think. But now, it’s not so unusual to consider art and performance together. I’m happy to say that even on the foundation front organizations are willing to accept performance under the rubric of “visual art.” This doesn’t mean there aren’t crucial theoretical and political issues yet to hash out. But the inter-relationships find better reception and discussion.

Beyond that distinction, maybe the big change is in speaking to an audience that is, on the one hand, much broader and yet, on the other hand, much smaller. Broader in that we are reaching a whole bunch of different artistic communities and constituencies based on the range of disciplines and demographics, but smaller in the sense that scale-wise, you aren’t printing 40,000 copies of something per month. Over the course of a year at The Kitchen, we’ll certainly house 40,000 people. But it ends up being more community based, meaning that the artists working here basically know who they are addressing, if not personally, then nevertheless in terms of who they are in dialogue with. So it is a kind of public sphere, which the magazine can also generate but which is more intimate here.

IToP

That brings us back to conversation. When you think about the terms, vocabularies, and concerns of that dialogue, what topics and words seem most compelling?

TG

Well, I think that there are certain things I can say about presence, which was the first term we took up in The Kitchen LAB: How has the relationship between body and representation, artist and audience, changed over the past half century? And how does the term operate differently in art versus performance, going back to the days of Minimalism?

That said, during the past year, the phrase “From Minimalism into Algorithm” [the frame placed around the 2015/2016 season, which served as the title for a year-long interdisciplinary exhibition and program] has been even more resonant than I thought it would be. It articulated the connection between Minimalism and industrial production in order to propose a counterpoint in a postindustrial economy, whereby one could discern a reversal of subject and object that offers, I think, a very compelling premise for much art-making now. To spell this notion out just a bit more, an example: consider Fried’s theatricality against atmospheric architectural environments, or the experience of one’s “history” while browsing the Internet as it determines what pages you encounter online. (One continually encounters one’s past as a fresh present.) The exhibition was inspired by looking at a generation of composers, from Reich and Glass, whose compositions were declared in their day to be in dialogue with industrial production; and yet their artistic “children” are literally using algorithms today in compositions. What if we looked at the past fifty years of art history while privileging the legacies of musical composition?

I think asking this question might press on the idea of what a practice is, as well as on the idea of changing relationships of temporalities. I can’t help but bring up the work of artist Paul Sietsema here, particularly as he makes contemporary objects seem made centuries ago . . . a contemporary medium is rendered a sort of artifact even while speaking to our own moment. He compares it to quantum physics, which seems relevant to much art being made now in terms of the simultaneous, varying positioning of audiences by works of art. This is another use of the term ambiguity.

IToP

In putting together this collection of keywords in contemporary art and performance, we are well aware that we are exploring a contemporary conversation that has a long history. When you think about experimentation across the arts in the twentieth century and experimentation in the twenty-first, do you think there is a difference? Or is it just reinventing old wheels?

TG

There are many differences, when it comes to performance—and the positioning of audiences within institutional settings whose structures are being renegotiated—but maybe for the purposes of our talk I’ll just propose an illustration. On most occasions now, you see a contemporary artist working across disciplines him- or herself. In previous eras, you might have been more likely to see projects in which one person was doing the composing, another the dramaturgy, another the painting. That difference reflects a different sense of responsibility for making art, when it comes to different registers of specific artistic knowledge. In the past, each artist had specific knowledge; more and more, contemporary artists seem to think that they should be responsible for all of the artistic knowledge in play within a given production. Histories are at risk of being lost. I think that this direction is something that is still being negotiated, both by artists and the organizations that house and present their work. I think the difficulties and exciting possibilities of this negotiation have been reflected in at least my five years at The Kitchen. It has been the premise of the LAB series—and your anthology project itself—the ways that techniques were being borrowed both with and without awareness of their histories, which are crucial to reconsider when surmising the character of disciplinarity today, even if only in counterpoint.

All that said, I’m also intrigued by how interdisciplinarity in institutions today conjures loft culture of previous eras, and yet the soft parameters for disciplines’ meeting are in fact very different now—and they carry a relationship with mediation in life.

IToP

Do you think the negotiation among arts disciplines and skills has changed even in the last five years? Both the LAB series and our project were prompted by debates around the appearance of choreographers in museum galleries—and conceptual artists making opera.

TG

I would say that, five years ago, there were incredible tensions about decontextualization: tension about whether protagonists in certain disciplinary contexts understood or appreciated the artistic skills and values of other contexts. But I think there was something about the decontextualization of particular skill sets and artistic knowledge that was illuminating. It showed differences from previous generations.

IToP

Do you think that the tensions from five years ago have lessened?

TG

Lessened? More museums large and small are making great efforts to create display scenarios that can accommodate the histories and temporalities of different mediums. And the anticipation and behavior of audiences themselves have perhaps not adjusted. Moreover, while the character of the presenting organizations has changed, so have the artists’ projects. Everyone is becoming smarter. And yet I suspect I might miss the tension, if everything ends up fitting too well. Which is to say maybe I’m less tense about tension now than I was five years ago.