Despite the ongoing insurrection against theatrical representation, there are more elements of theater in the language of modern and contemporary art than either of the disciplines bargained for. General optics and space metaphors with philosophical and political meanings abound (for example, perspective and depth), while the use of terms like staging, spotlight, and scene has not been restricted to illusion but rather is applied to all kinds of dramaturgy of the surface, regardless of whether it came through minimalism, conceptualism, or installation art. Needless to say, an attempt to map the genealogies and impact of these theatrical elements would be comparable to talking about the role of climate change in weather dynamics. (Well, actually it might not be the most fruitless discussion.)

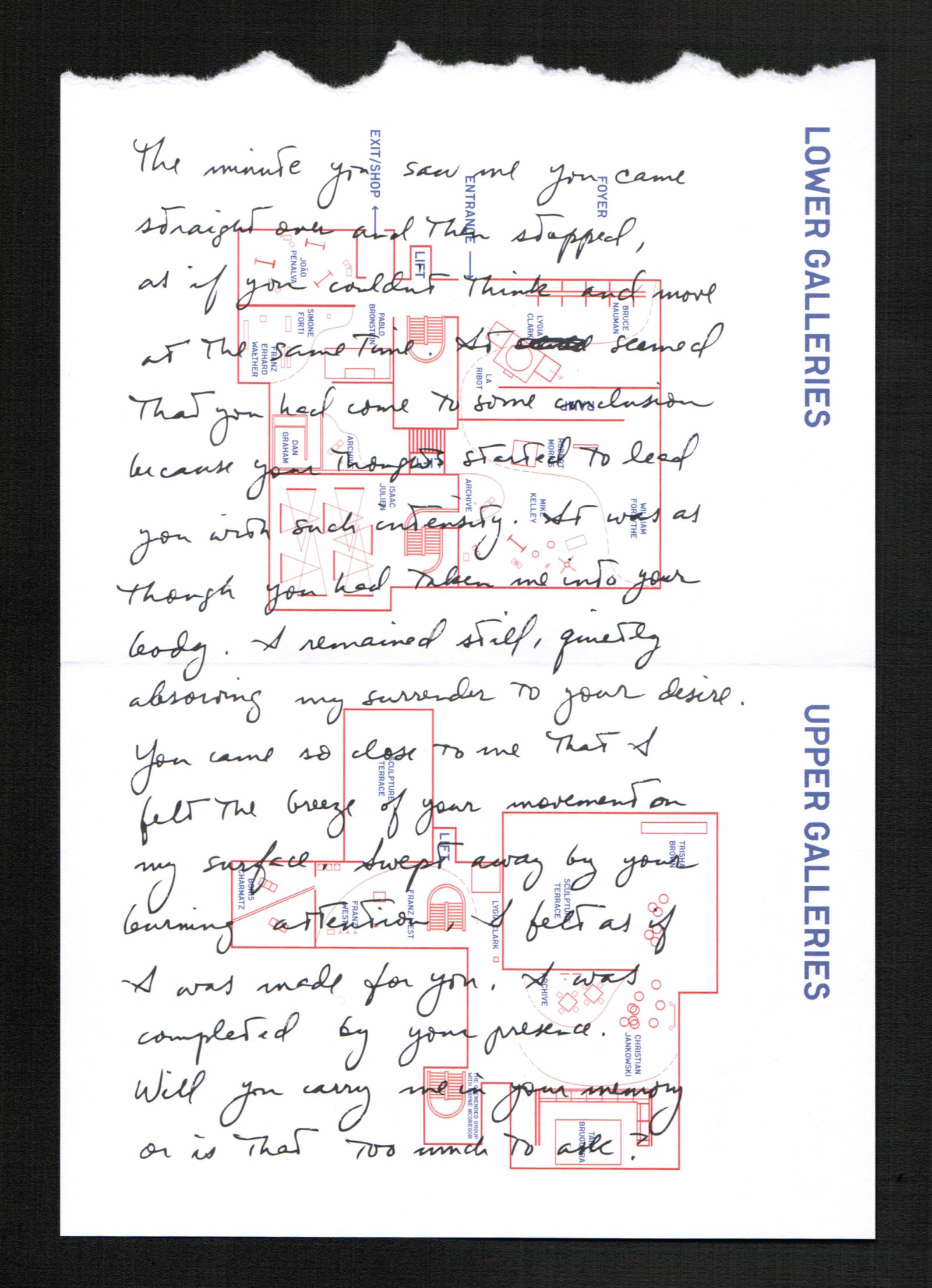

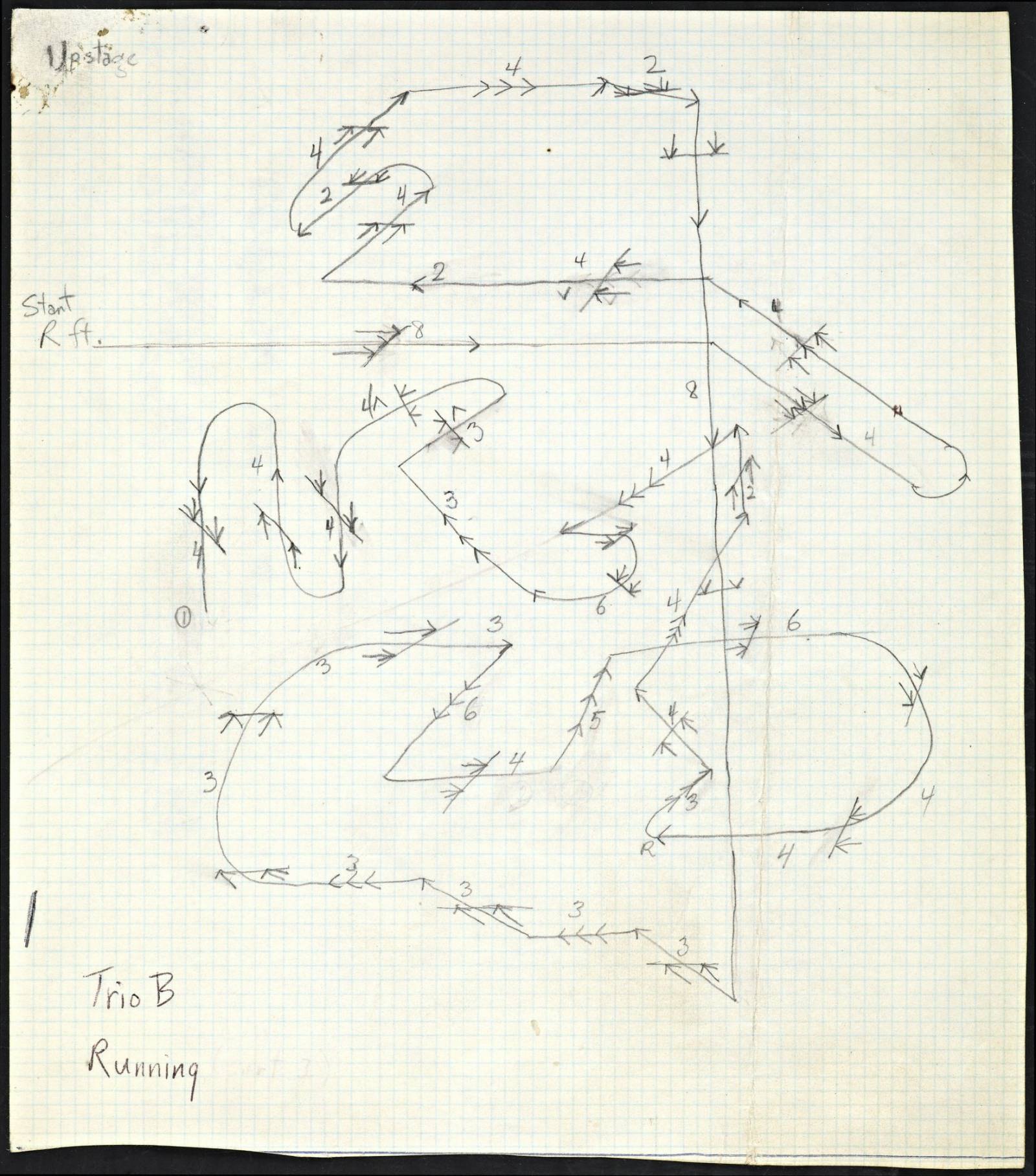

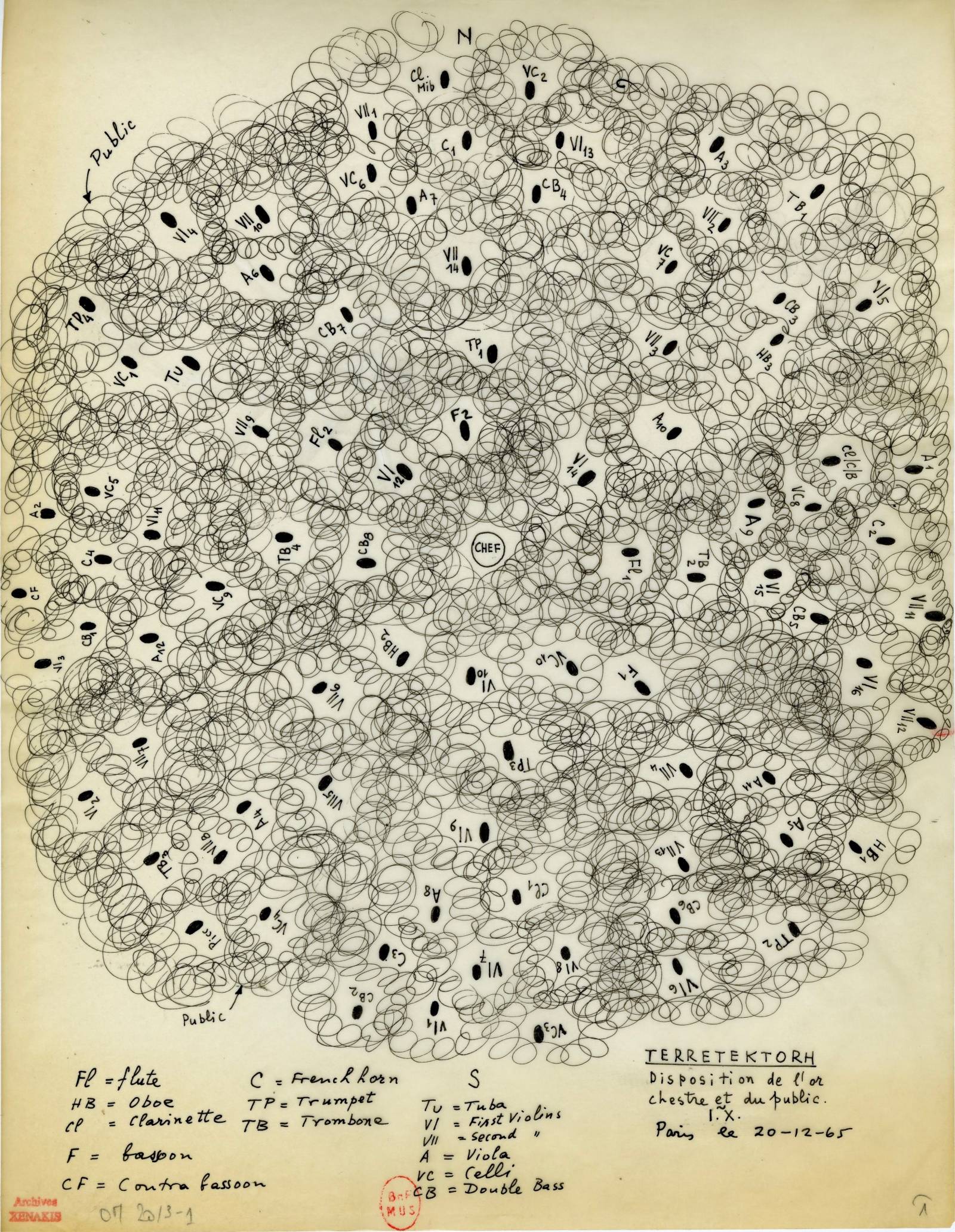

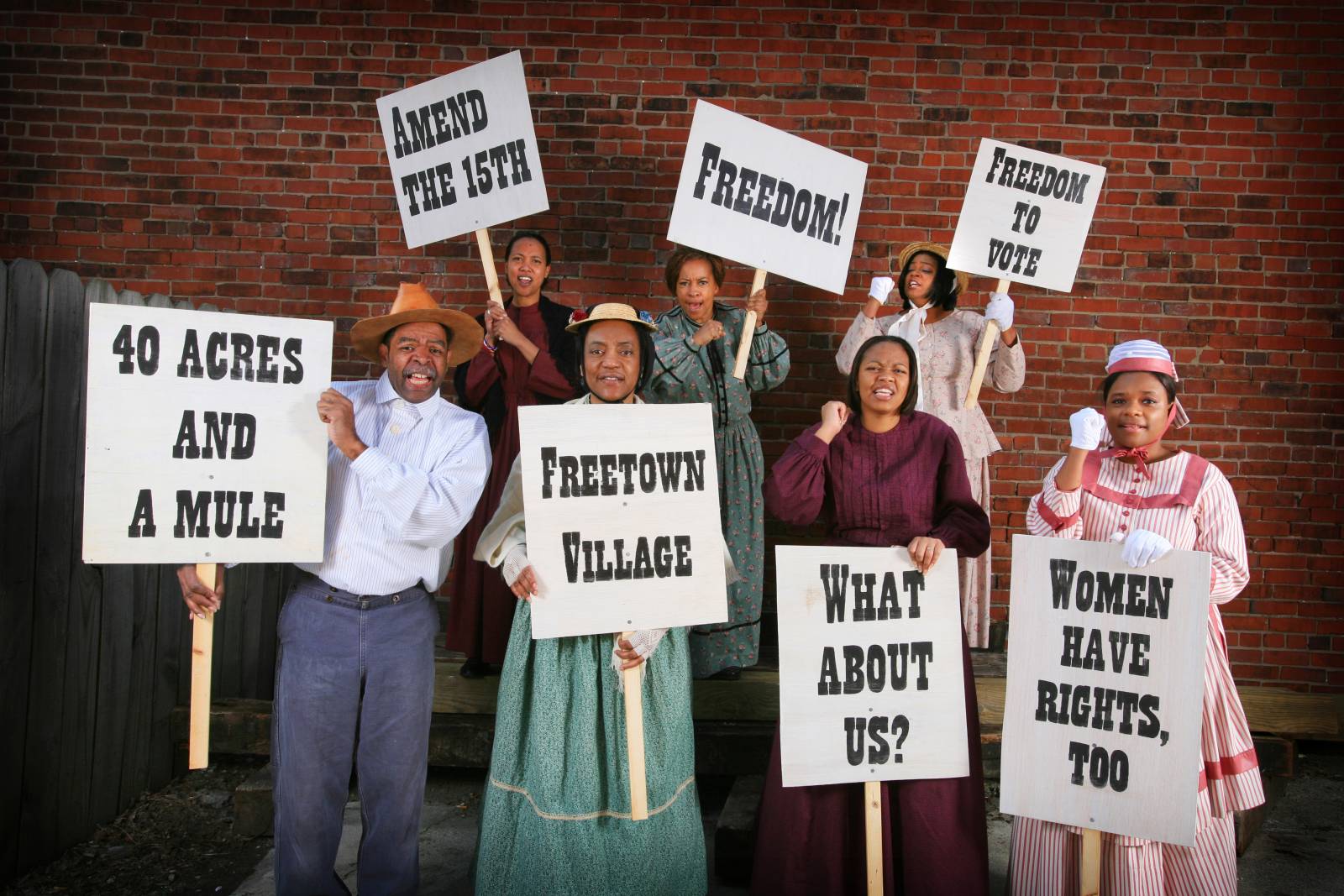

Some areas of more complex public organization—like exhibition making—employ certain theatrical mechanics, namely space-time management involving multiple actors (artworks, conditions, and sites). The curating of exhibitions now uses the language of both logistics management and choreography. A recent publication by Mathieu Copeland titled Chorégraphier l'exposition (Choreographing exhibitions) brings the latter into full force. Artists may write their own scripts and perform them in a pastoral setting with friends; Jessica Warboys, for example, staged several theatrical soirées in parks and forests. Theatrical language can appear in more art-historical frameworks too: curators at the Contemporary Art Centre Vilnius became so inspired by the theatrical machine that they dedicated an entire exhibition to it.

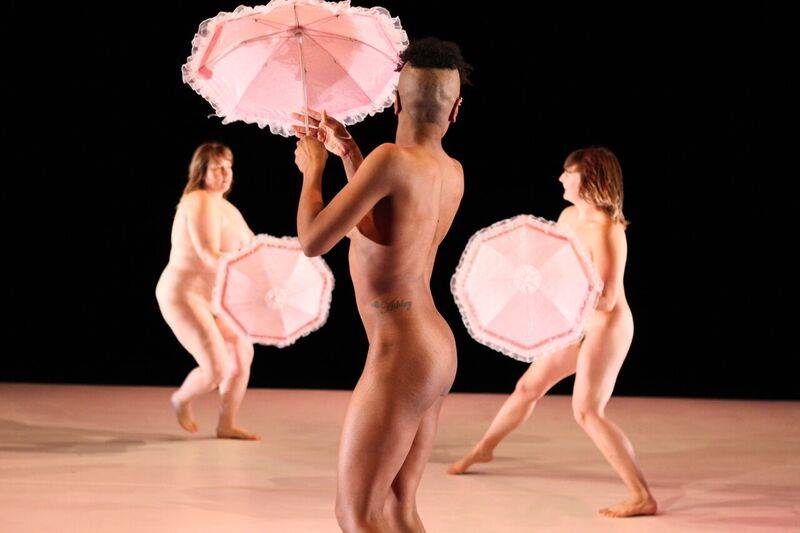

Meanwhile theatricality can manifest itself as a stage solo or duo act in which the body of the artist is present and attention is skillfully mastered. Perhaps commanding attention is one of the key forces of theater? Think of Michael Portnoy and Ieva Misevičiūtė, Liz Magic Laser, Sharon Hayes, and so many more.

It is worth noting that an exhibition, as an organization or a certain ecosystem, tends to incorporate its own parameters as one of the elements of the display; it is not—or is no longer—just a frame that defines the field of the play and remains invisible itself. Theatricality occurs either through the art projects that constitute the exhibition (its organizational framework) or through other sets of circumstances, neither of which is considered fixed. Driven by this logic of individual urgencies and collective intelligence, artworks, artists, curators, ideas, sites, schedules, and sponsors may cohabit a critical poetic temporary universe that has much more in common with the museum than with theater. Yet it draws on the logistics of both. On the surface it may look like an intellectual tableau vivant or a fashion shoot—that is, a seamless merger of white cube, performance, and theater mechanics—yet these worlds face their deepest disparity at the level of economics. While the art world economy is a speculation-based financial business, theater runs on the regularity of a paycheck enabled by state support or by ticket sales.

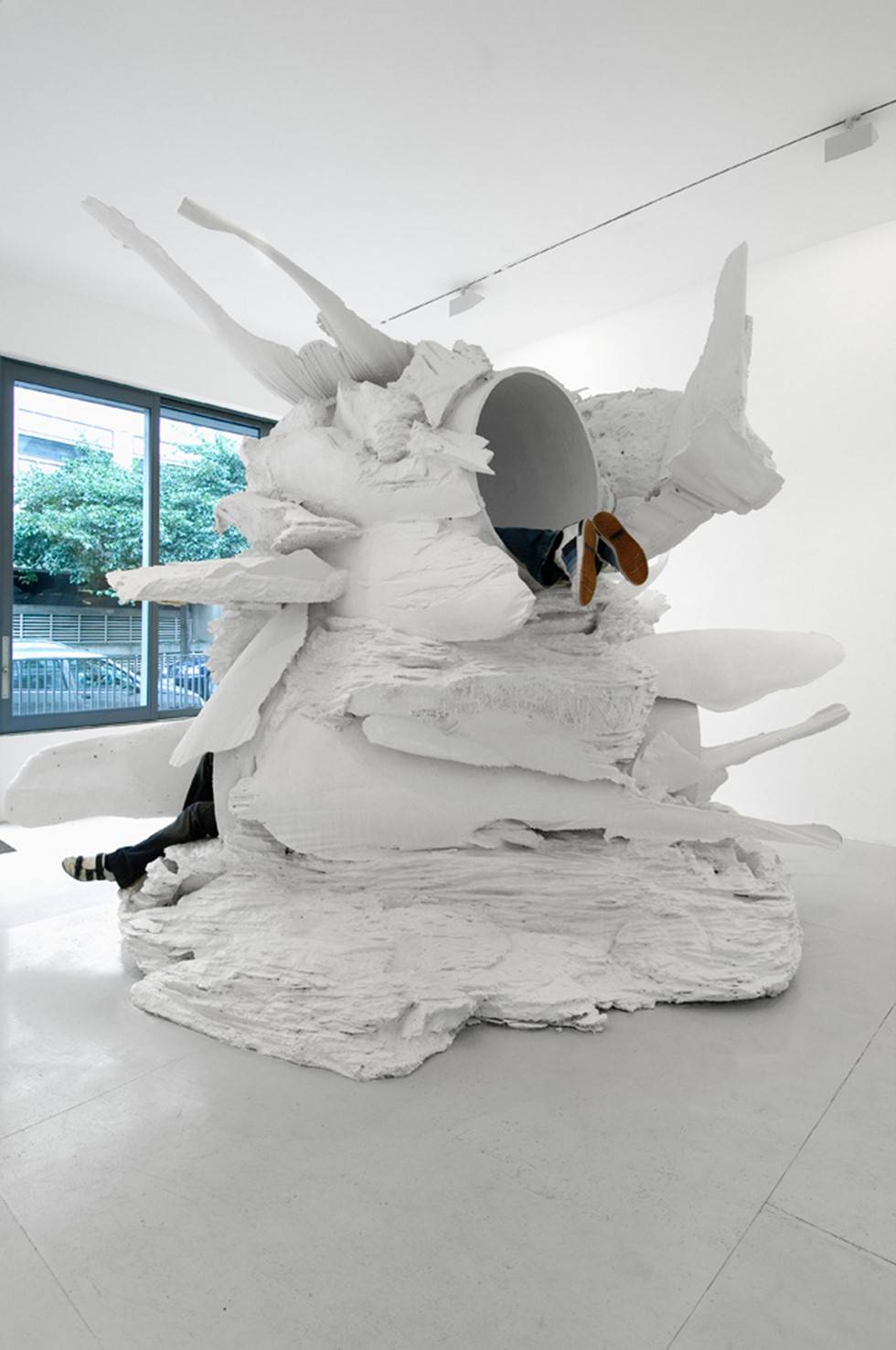

Combined with the performative turn of the art world in its journey with the current information economy, these material conditions have produced interesting phenomena. For instance, one can boldly speculate that about as many actors and actresses have been employed by art museums, fairs, and galleries in the last ten years as in the prior ten decades. The artist duo Goldin+Senneby not only employed actors but also staged their exhibitions with the help of a professional set designer. Despite appearances, this development does not constitute a two-way movement of labor force: hardly any contemporary artists have landed in the theater. (David Levine is an exception who oscillates between the two fields.)

I have not yet mentioned the important figure of the spectator. His or her presence is acknowledged very differently in theater than in the art world. It is hard to imagine a theatrical play running on the stage if the audience is not there, while it is quite common to visit exhibitions and not meet anyone else. Yet suddenly the quest for a dynamic and not an abstract spectator has become not just the goal but the condition of art-world performance. This transference of the awareness of the spectator from theater to the art world has generated a genre of performance in which the spectator symbolically ends up onstage: think of Tino Sehgal’s entire oeuvre.

I want to mention one last interesting thing about theatrical representation and illusion. I remember when I was younger how mysterious and attractive elements of stage design depicting castles and trains looked from the perspective of the audience. I used to be afraid that all that allure would evaporate if I got onstage and saw them close-up. The effect was the opposite, however: those trains and castles became even more interesting when I stepped onto the stage.