Judy Hussie-Taylor

Judy Hussie-Taylor is executive and artistic director of Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery in New York, where she established the Platform series of programs and performances.

Curate. Probably 1382. Spiritual guide, one who cures, in writings of Wycliffe; borrowed from Medieval Latin curatus, person having the care of souls, from cura care. The meaning of a clergyman who assists a vicar was first recorded in 1557, and originated in the Church of England.

Curator. Probably about 1375, curature, person having the care of souls, borrowed from the Anglo-French curatour, Old French curateur, learned borrowing from Latin curatorem (nominative curator) overseer, guardian, from curare care for, from cura care.

—Chambers Dictionary of Etymology

It is good to be reminded that the original usage was about caring not for objects but for people. Relationships are central to curating performance; it is caring for the art and the people who make it. Might a performing arts curator be a connoisseur of relationships and situations, an expert in the care of time and ephemerality as much as of space?

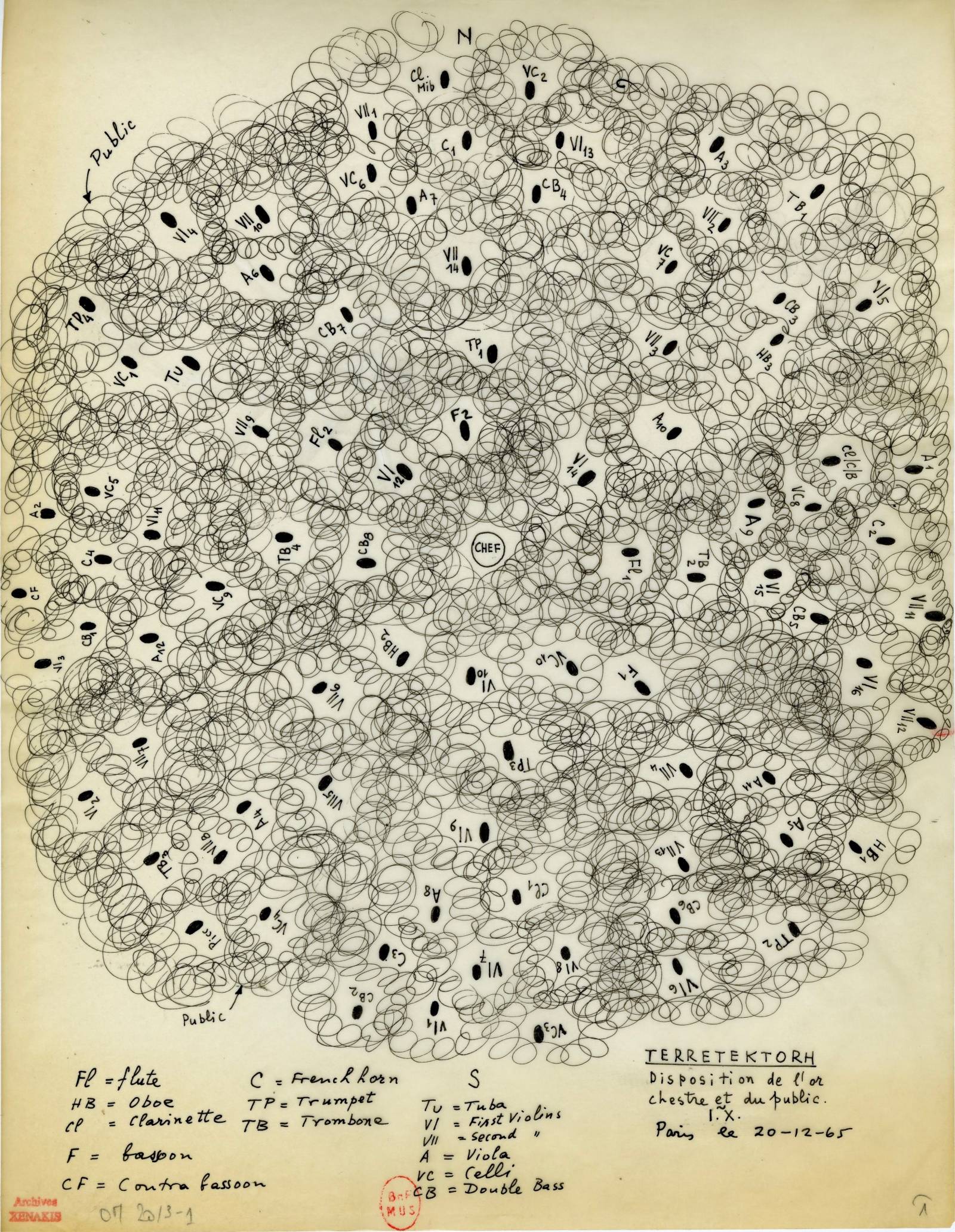

The curator is commonly understood to be the person who oversees a collection of historical and/or art objects and one who creates exhibitions that contextualize those objects. The term has been applied historically to the visual arts and most often to static objects displayed in museums and galleries. In the 1960s and ’70s the curator’s role became increasingly dynamic in response to contemporary artists who were reimagining artistic practice and creating works of art outside the context of galleries and museums, often involving performance. As the legendary curator Harald Szeemann put it, “An exhibition is . . . a poem in space with plenty of room for free association.”

The application of the term curation to performing arts is relatively new, but the function of curation is not. The performing arts curator’s role is usually embedded in her other functions as executive director, producer, presenter, manager, fundraiser, operations manager, and/or artistic director. We have of course had impresarios, including Sergey Diaghilev and, more recently, Harvey Lichtenstein, who put the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) on the international map in the 1980s through his decades-long support of Merce Cunningham, Pina Bausch, Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, and Lucinda Childs, among other artist luminaries. BAM and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis were among the first institutions to create formal positions for performing arts programmers with the word curator in the title. Since the 1970s the Kitchen in New York has engaged scholar-curators and artist-curators. Danspace Project used the term on its founding in 1974 with the distinction that its first curator, Larry Fagin, was and is a poet. He reportedly learned about dance from the poet and dance critic Edwin Denby. It would be heartening to see more hybrid curatorial teams working across disciplines, and I hope that there will be more curatorial experiments and collaborations moving in this direction. The curators of different art forms have much to offer one another.

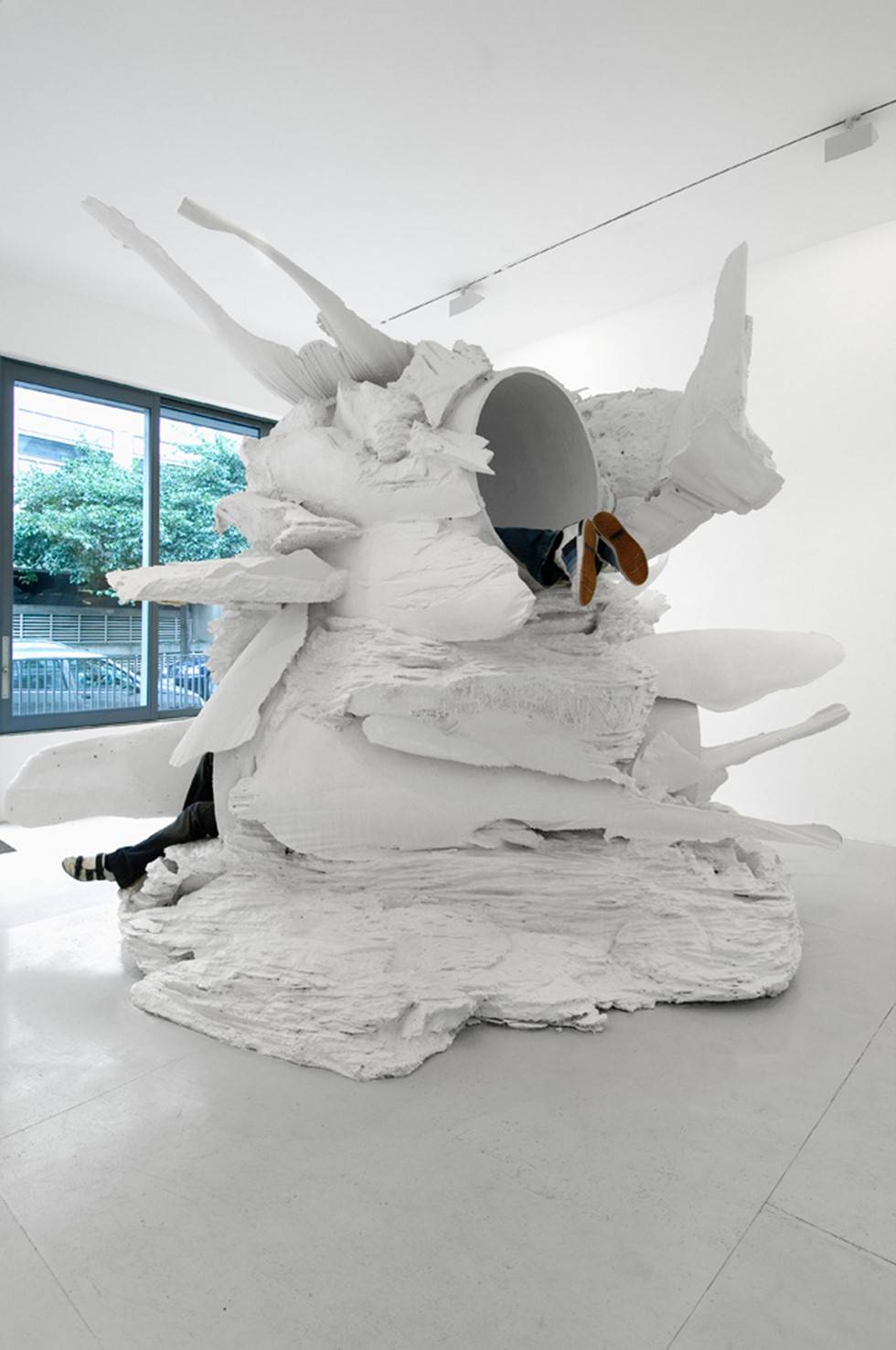

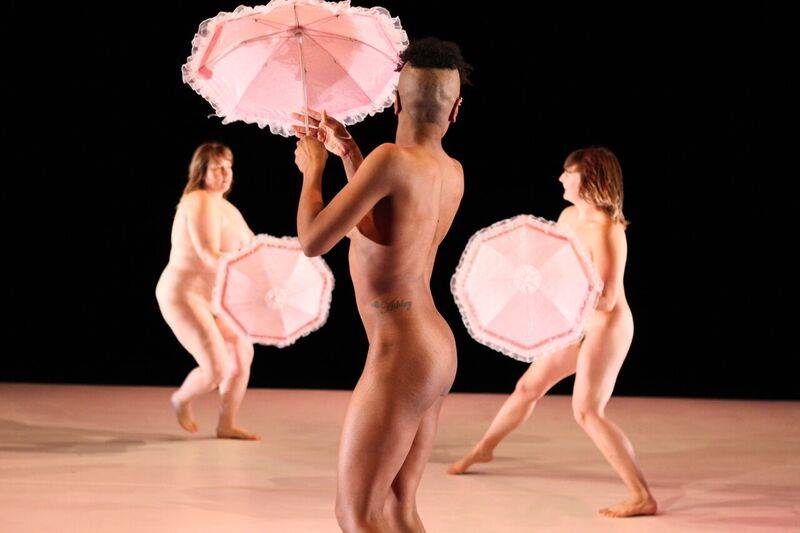

Any curator engaged with contemporary exhibition making is involved in relationships with living artists. Perhaps what differentiates artist-curator relationships in the visual arts from those in the performing arts is that visual artists’ and curators’ work is primarily behind the scenes in preparation for an exhibition. In the performing arts, curators’ relationships and negotiations with artists take place before, during and after the event or performance. When the dancer exits the stage, the performance space, or for that matter MoMA’s atrium, where does she go? What does she need? She probably needs a glass of water, a bathroom, and a few quiet moments to catch her breath. As mundane as this sounds, the performance curator and her staff understand that those needs are as essential to the work as contextualizing, research, and presentation. But perhaps the differences matter less than the primary similarity: the fact that at the heart of the best curation lie an intimate knowledge of and relationship to living artists.

In her introduction to On Curating, Carolee Thea writes, “Among the major figures to have come of age in this cultural milieu is the independent curator. . . . Aesthetically, curators are more like theater directors, and it could be argued that they follow a performance paradigm rather than one based on the object or commodity. We could say that they are translators, movers or creators whose material is the work of others—but in any case the role of mediator is inescapable. . . . The curator inversely translates the artist’s work by providing a context to enable the public’s understanding.”

In the performing arts, “curation” has not been codified to the same degree that it has in visual art; many presenters and organizers reject the term, perhaps because most do not have advanced degrees in art history or curatorial studies. At the same time, some visual art curators have recently questioned the title because of its overuse in popular culture. Today everyone is the curator of her own consumer experience! Every recent college grad who organizes an informal works-in-progress series is a curator! That said, training in performing arts presentation can be quite rigorous. Performing arts organizers tend to get trained in real time, under extreme pressure, or, in the best cases, by mentors, but they are always, it seems, under fire. Often performing arts organizers have been trained as artists of some kind before becoming curators. Until 2012 there was no program in the United States in which one could study or research performing arts curation.

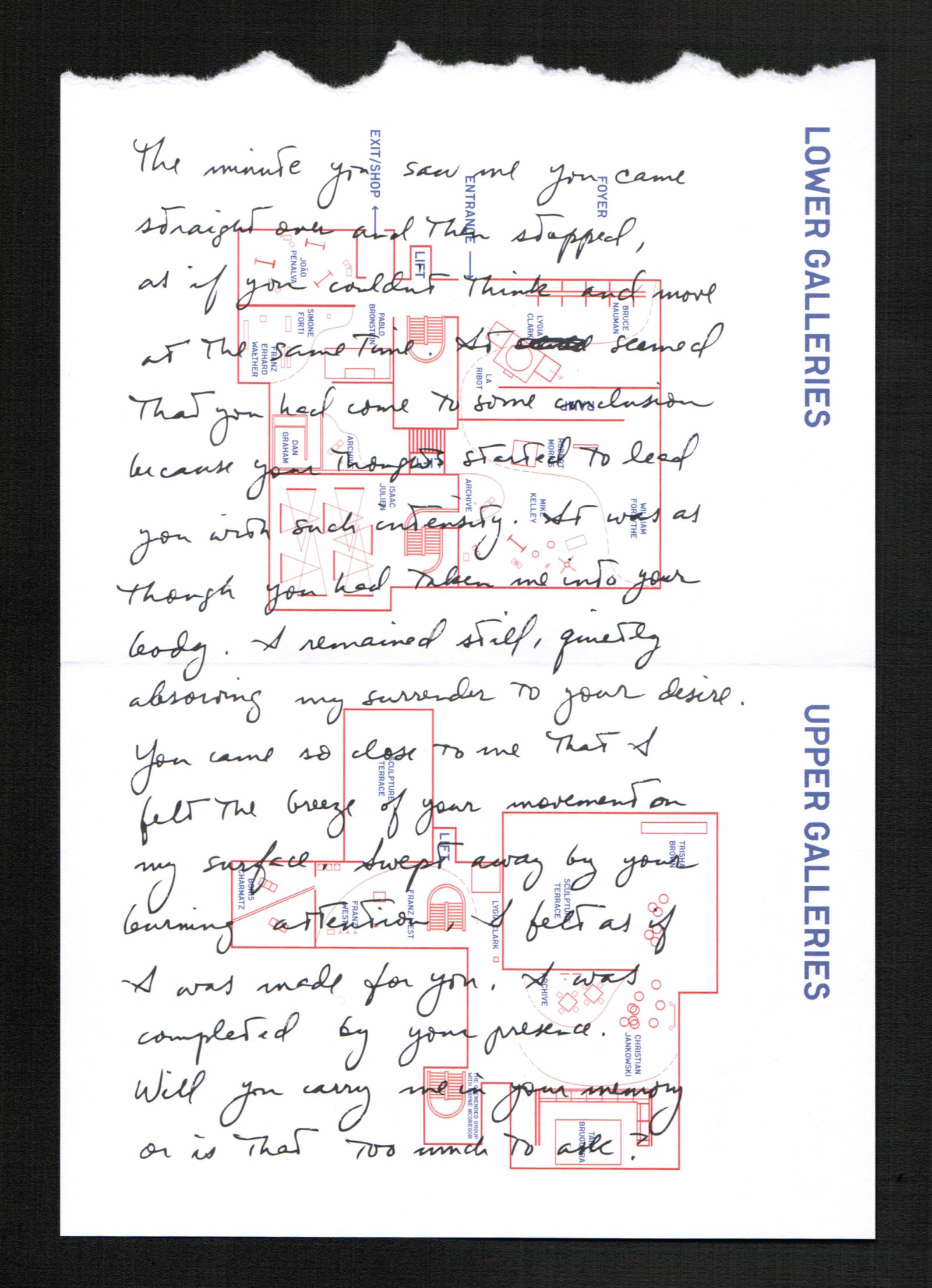

The curatorial strategies that we have explored at Danspace Project since 2008 include the Platform series, which was conceived as a set of exhibitions that unfold over time. The Platforms are predicated on relationships between artists, curators, scholars, historians, writers, and audiences. I often exercise poetic license by playfully referring to our collaborative curatorial process as “relational curation.” And, while not directly influenced by Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics, the notion that an artistic endeavor takes into account “the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an independent and private symbolic space,” resulting in “collective elaboration of meaning” is applicable to the coauthored organizing of the Platform series. In Hans Ulrich Obrist’s A Brief History of Curating, Christophe Cherix writes that a history of contemporary curation is important because it highlights “a network of relationships within the art community at the heart of emerging curatorial practices.” An active network of relationships at the heart of the dance community provides the scaffolding for the Danspace Project’s Platform series, which is but one component of Danspace’s Choreographic Center Without Walls, a center for artistic and curatorial research.

For Further Reference

Note: Four of these six exhibitions were curated by artists.

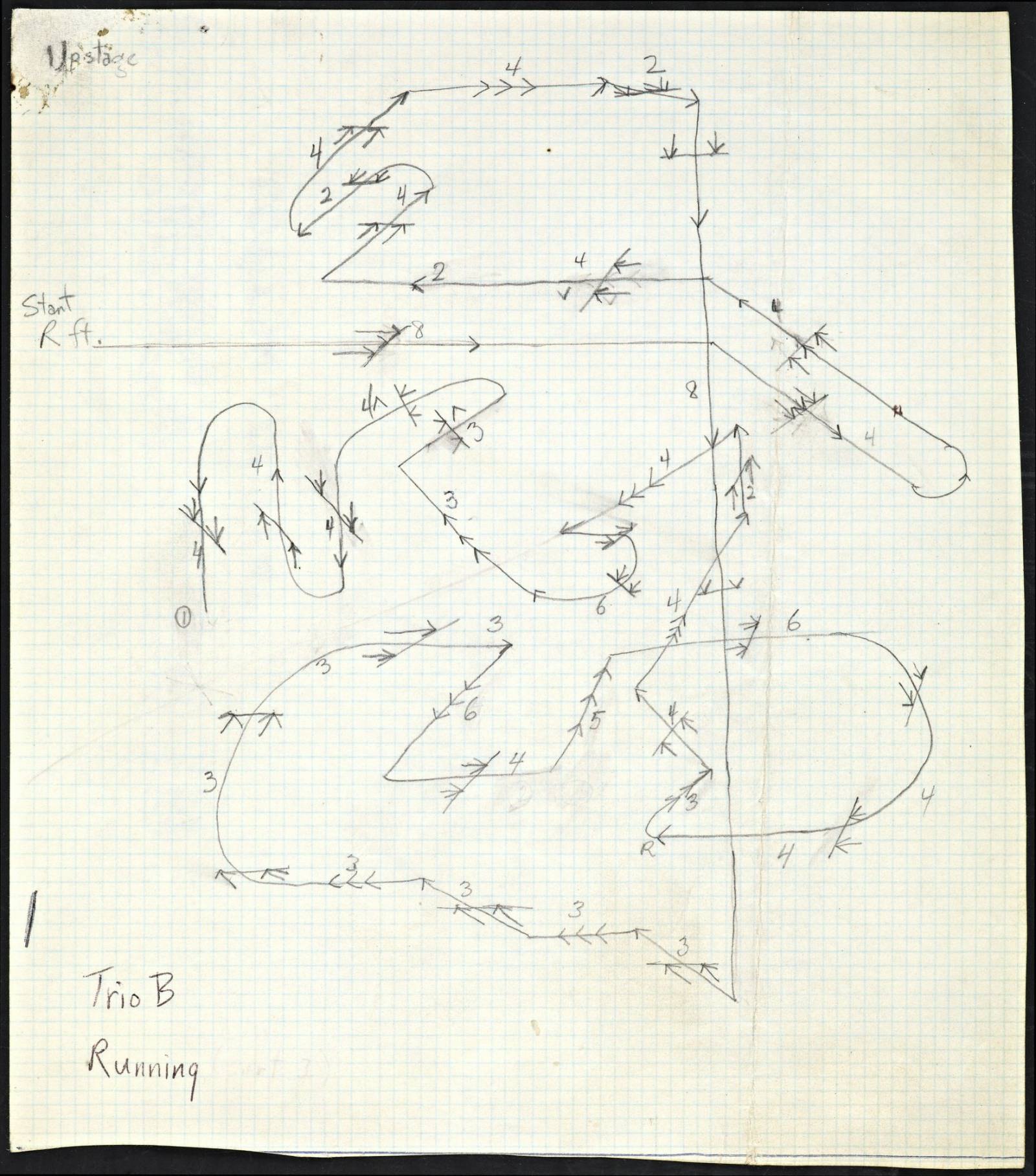

First New York Theater Rally, abandoned CBS studio, Broadway and Eighty-first Street, New York, May 1965. Curated by Steve Paxton and Alan Solomon. Artists: Lucinda Childs, Jim Dine, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Robert Morris, Claes Oldenberg, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, and Robert Whitman.

“Some Sweet Day,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, October–November 2012. Curated by Ralph Lemon with Jenny Schlenzka. Artists: Steve Paxton, Jérôme Bel, Faustin Linyekula, Dean Moss, Laylah Ali, Kevin Beasley, Deborah Hay, and Sarah Michelson.

“PLATFORM 2012: Judson Now,” Danspace Project, New York, September–December 2012. Curated by Judy Hussie-Taylor (with one-time-only events curated by Steve Paxton, Juliette Mapp, Patricia Hoffbauer, and Melinda Ring). Artists (in order of event): John Cage (100th birthday celebration), Rashaun Mitchell, Silas Reiner, So Percussion, Elaine Summers, Steve Paxton, Stephen Petronio, Yves Candau, Clarinda Mac Low, Jackson Mac Low, Lucinda Childs, Carolee Schneemann, Stacy Spence, Trajal Harrell, David Gordon, Valda Setterfield, Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti, Ralph Lemon, Juliette Mapp, Lance Gries, Molly Lieber, Eleanor Smith, Jen Rosenblit, Melinda Ring, Liliana Dirks-Goodman, Michael Mahalchick, Meredith Monk, Martin Kersels, Patricia Hoffbauer, Pat Catterson, Sara Rudner, Arthur Aviles, Jennifer Monson, Sally Silvers, Claire Bishop, and Deborah Hay.

Time-Based Art Festival, Portland Institute of Contemporary Art. Curated by founder Kristy Edmunds from 2003 to 2005 (subsequent curators include Mark Russell, Cathy Edwards, and Angela Mattox).

“Retrospective Project: Eiko & Koma,” multiple US venues (Wesleyan University, Danspace Project, Park Avenue Armory, Walker Art Center, Columbia University, Tigertail, RedCat, Baryshnikov Arts Center, Dublin Dance Festival, Alverno Presents, Lincoln Center, MCA/Chicago, Skirball Center, North Fourth Art Center, Astor Galler/NY Public Library for the Performing Arts, Colorado College, Brown University, Yerba Buena Center for the arts, Clarice Smith Performing Arts, University of Maryland), April 2009–June 2012. Curated by Eiko & Koma in collaboration with Sam Miller (with site-specific co-curators: Philip Bither, Rachel Cooper, Irene and Paul Oppenheim, Jodee Nimerichter and Charles Reinhart, Ralph Samuelson, Yoko Shioya, Jan Schmidt, Peter Taub, Pam Tatge, and Judy Hussie-Taylor).

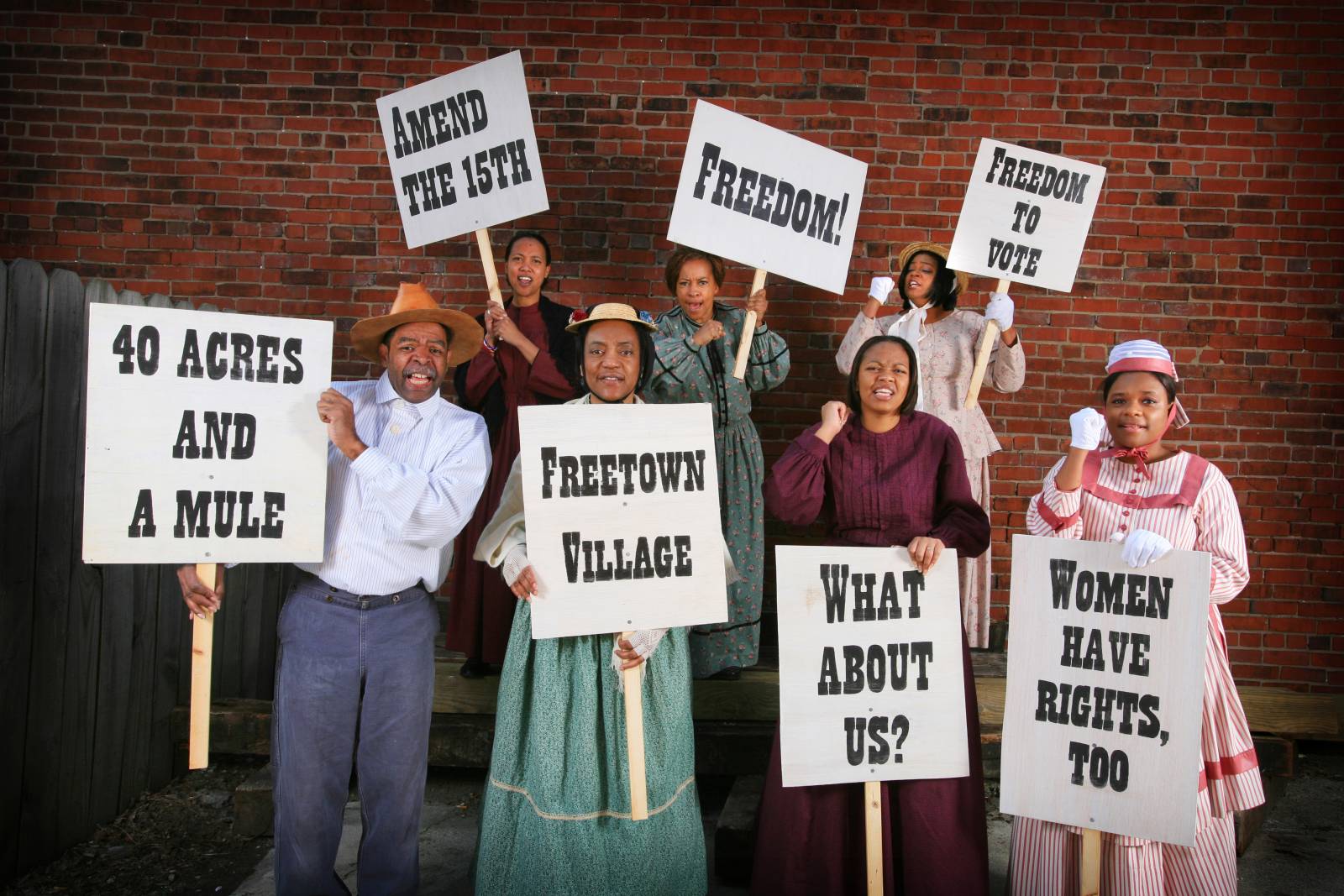

“Daylight,” Walker Art Center, September 2005. In response to the Herzog & de Meuron Walker Art Center Building. Choreographer: Sarah Michelson. Collaborators: Claude Wampler and Dominic Cullinan. Curated by Philip Bither.