Sabine Breitwieser

Sabine Breitwieser, formerly chief curator of media and performance art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, is director of the Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, Austria.

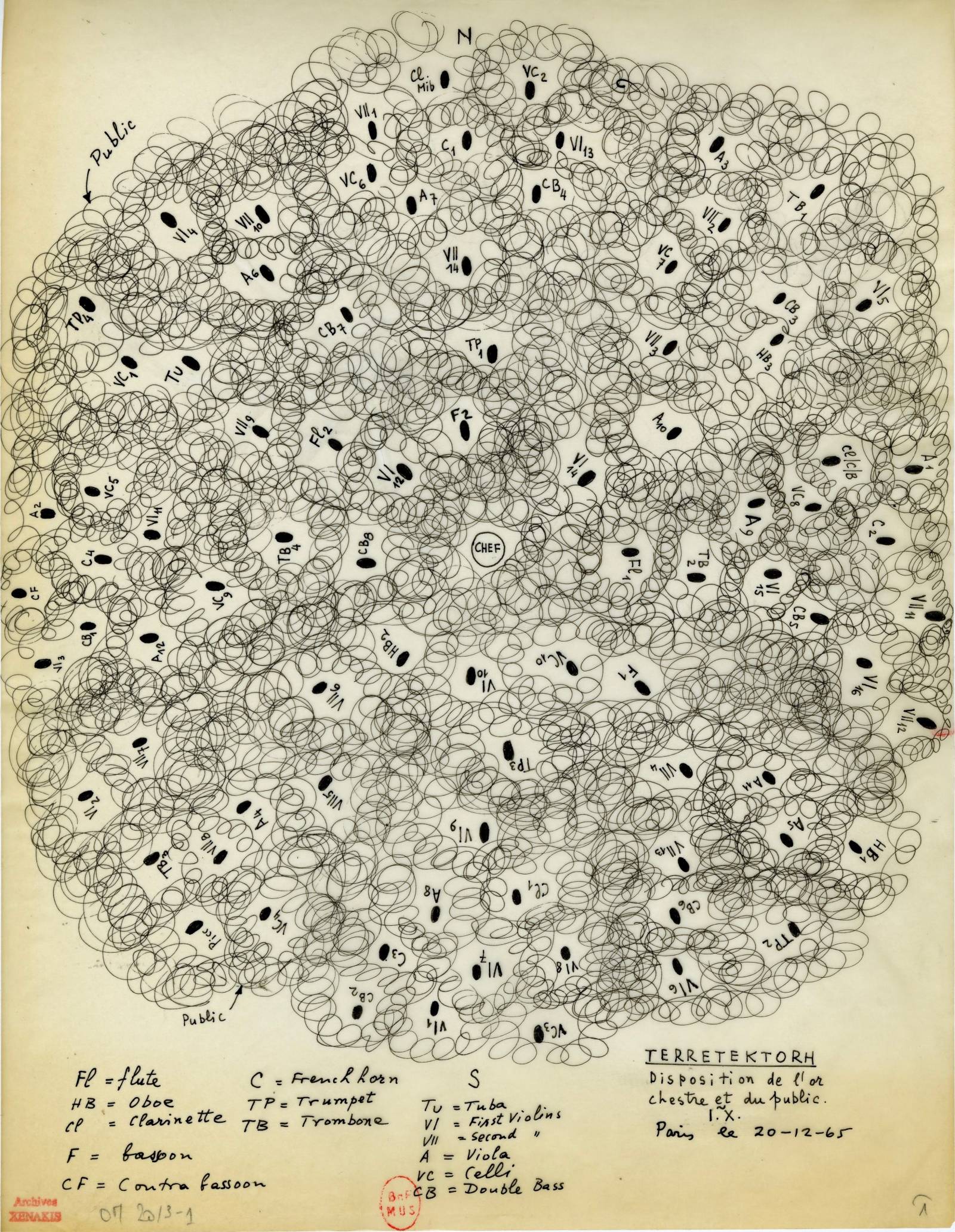

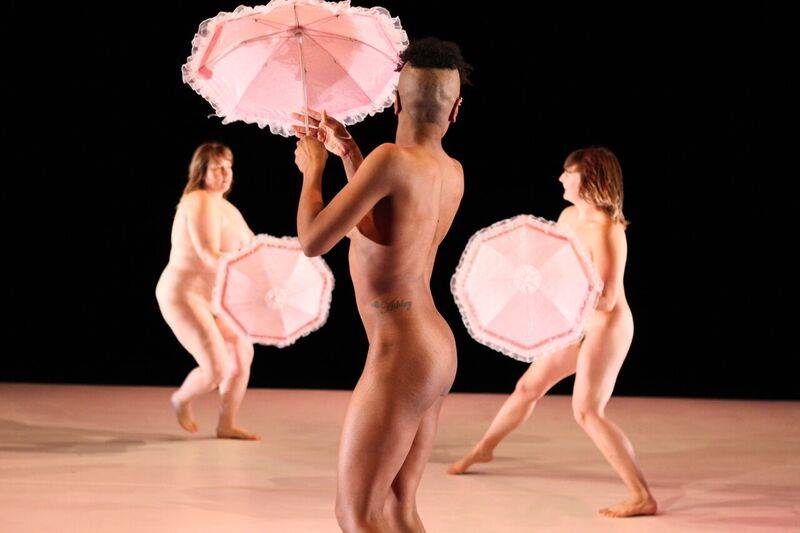

Choreography is understood as a sequence of movements and their composition, usually in dance, but more recently the term has been applied to the creation of scenarios in general. Choreographers take on a creative double role as authors and directors; their material consists primarily of people. In ancient Greek tragedy, choros described the demarcated dance floor and ultimately the song, dance, and commentary of those performing. In the eighteenth century, chorégraphe (French for “dance” and “writing”) described someone who recorded dance steps in writing. From dance notation emerged the task of “composing” movement—that is, mere recording became a creative act. This transition was augmented by a collective process of rehearsal, giving recording a lesser role. The notion of choreography was an important element of experimentation in modern and postmodern dance. In collaboration with visual artists such as John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg in the mid-1950s, Merce Cunningham introduced the idea that composition could be entrusted to the principle of chance and, beginning in 1991, even to a computer program. In the first half of the 1960s the artists of Judson Dance Theater, including Yvonne Rainer and Steve Paxton, and others, such as Simone Forti, swore off virtuosity and instead drew their movements from the everyday.

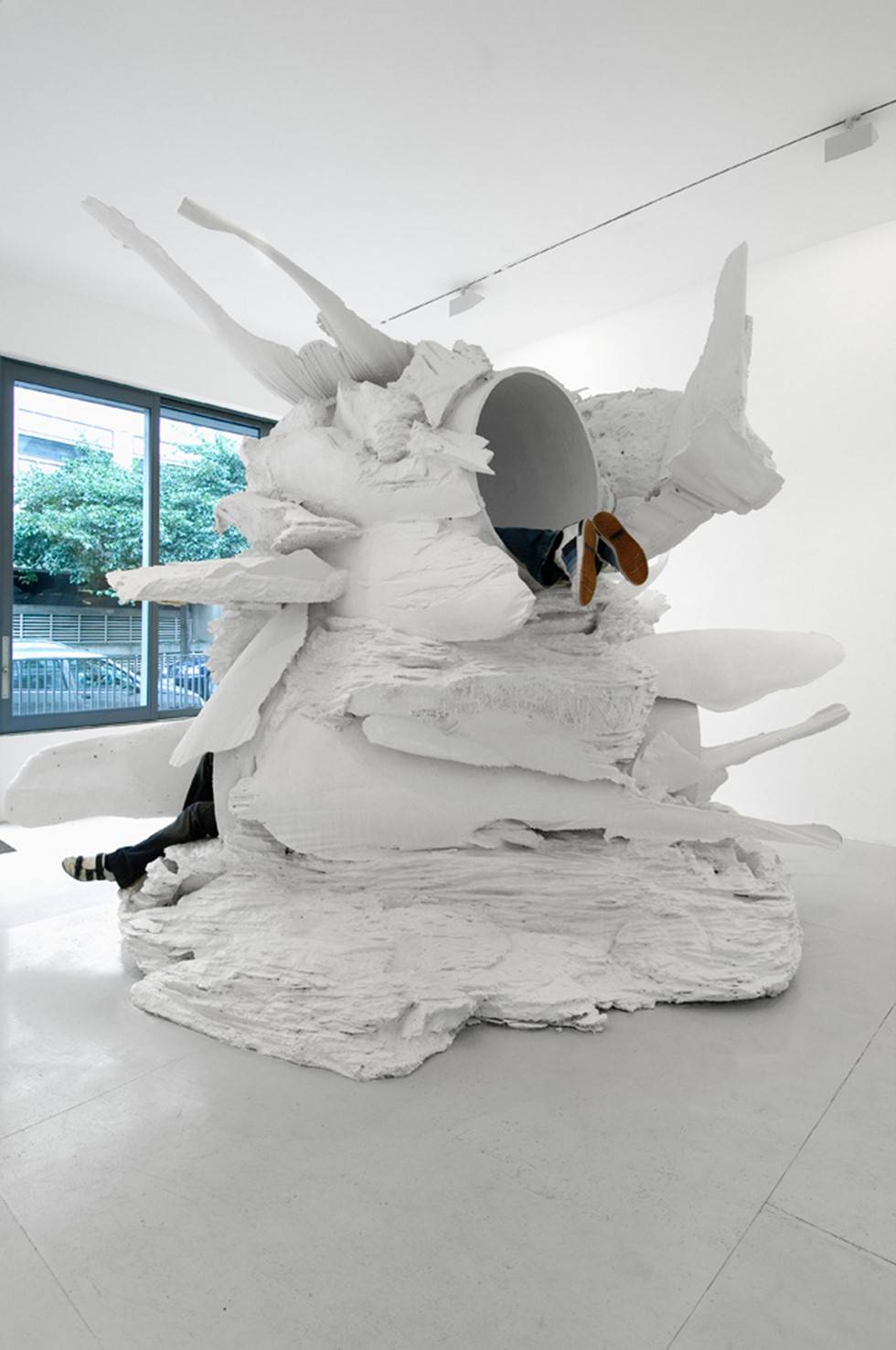

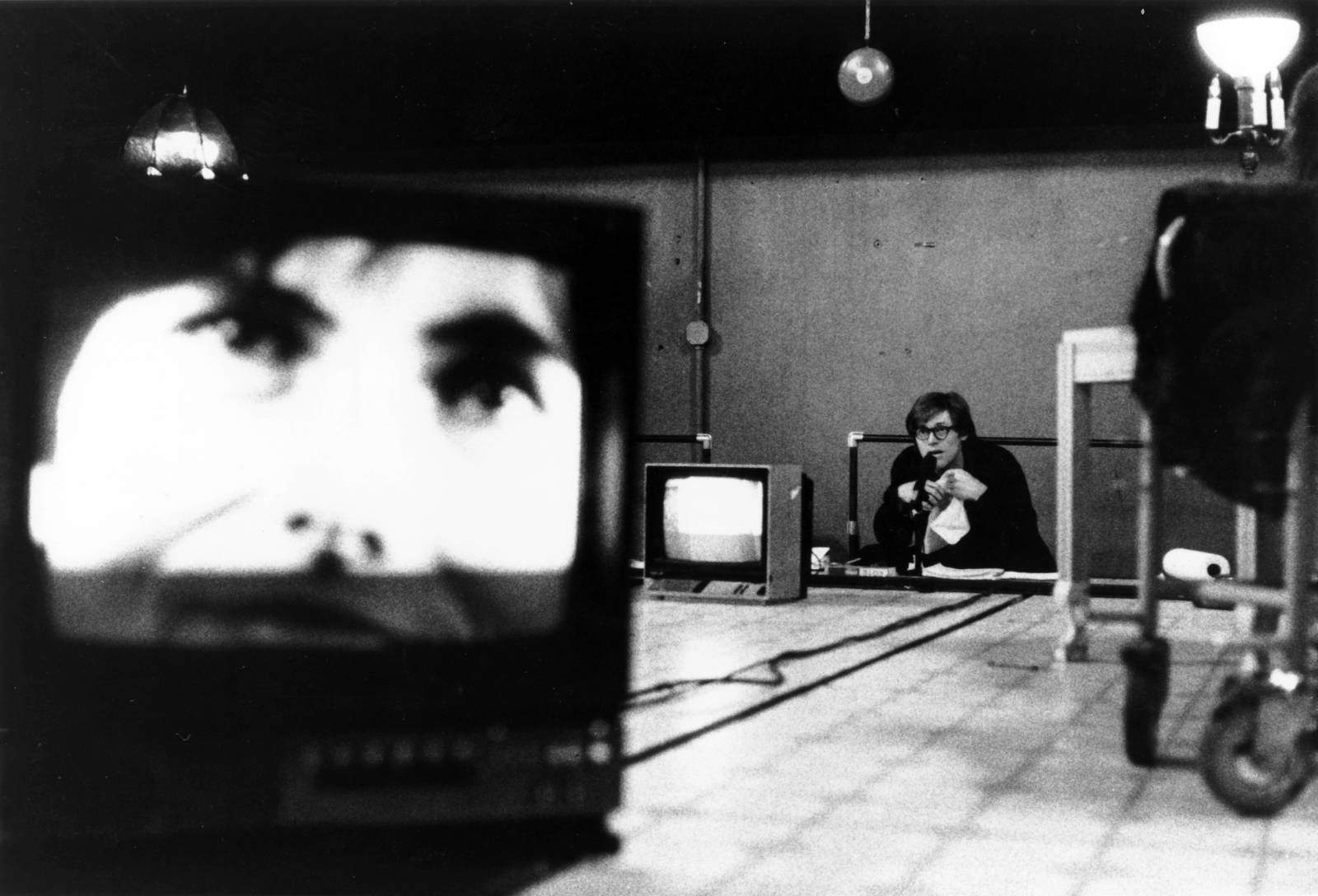

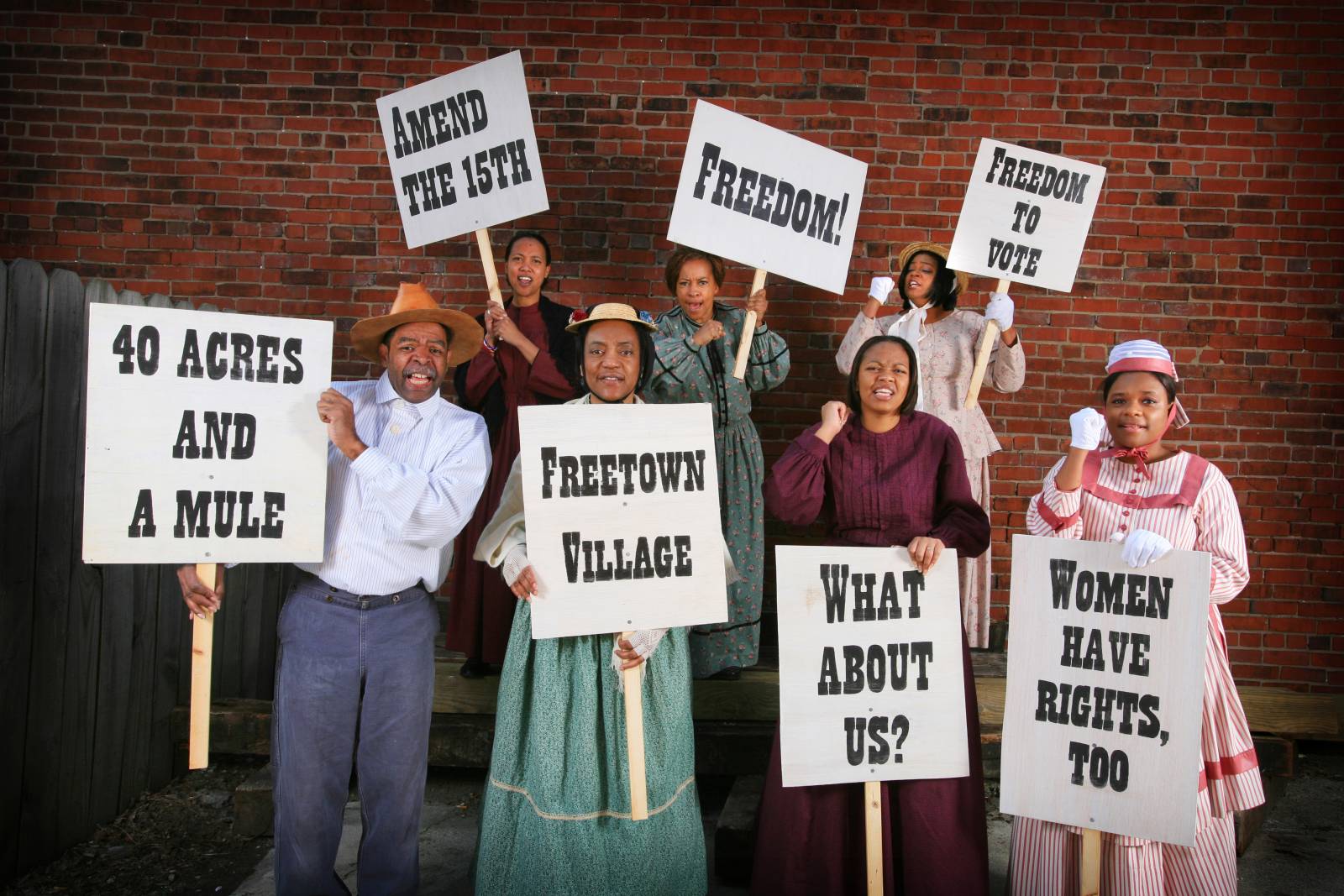

While organizing and controlling human figures is a fundamental principle in scenic art forms, primarily in the fields of dance and theater, that practice is not conventional in modern visual art, in which painting and sculpture appear as autonomous art forms. Conventions, however, have changed. By considering architectural space in art, artists such as El Lissitzky in Prounenraum (Proun room, 1923) made the organization of the art object in space and its encounter with the viewer a major factor in their work. One could say that artists started to choreograph their artworks like actors in a theater play in space. In Triadisches Ballett (Triadic ballet), which premiered in 1922 in Stuttgart with music by Paul Hindemith, Oskar Schlemmer had already grappled with questions of the relation of the object to space, trying to overcome the static nature of plastic works with dance. The expansion of fine art to include forms and mediums with intrinsic temporal elements—music, language, moving images, objects, and people—radically changed the concept of art. This also affected art’s relationship to audience and the site of art reception. In 1916 artists in the circle of Hugo Ball—including Hans Arp, Emmy Hennings, Marcel Janco, and Tristan Tzara—started their “cabaret” at the artist’s bar Voltaire in Zurich under the motto “Everybody is welcome.” What began as a protest movement against World War I turned into an art form with far-reaching consequences, including the international Dada movement. In 1958 the so-called Wiener Gruppe (Vienna group) of Friedrich Achleitner, H. C. Artmann, Konrad Bayer, Gerhard Rühm, and Oswald Wiener performed their 1. literarisches cabaret (First literary cabaret) at the Alte Welt (Old world) artist association in Vienna, demonstrating their idea of artistic choreography in the repressive cultural climate of the post–World War II period. These and many other historical events gave the impression of a broadening of rigid single-discipline art forms, accompanied by a departure from established art institutions. The following year, Allan Kaprow used detailed written instructions (scores) to transform visitors to his 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959) at New York’s Reuben Gallery into participants in an interactive environment. When asked in 1967 what he expected a museum of his time to be, Kaprow declared, “an educational institute, a computerized bank of cultural history, and an agency for action.” In performances disguised as museum tours, like The Public Life of Art: The Museum (1988) and Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk (1989), Andrea Fraser used institutional markers such as sponsor boards to tell a museum’s social history.

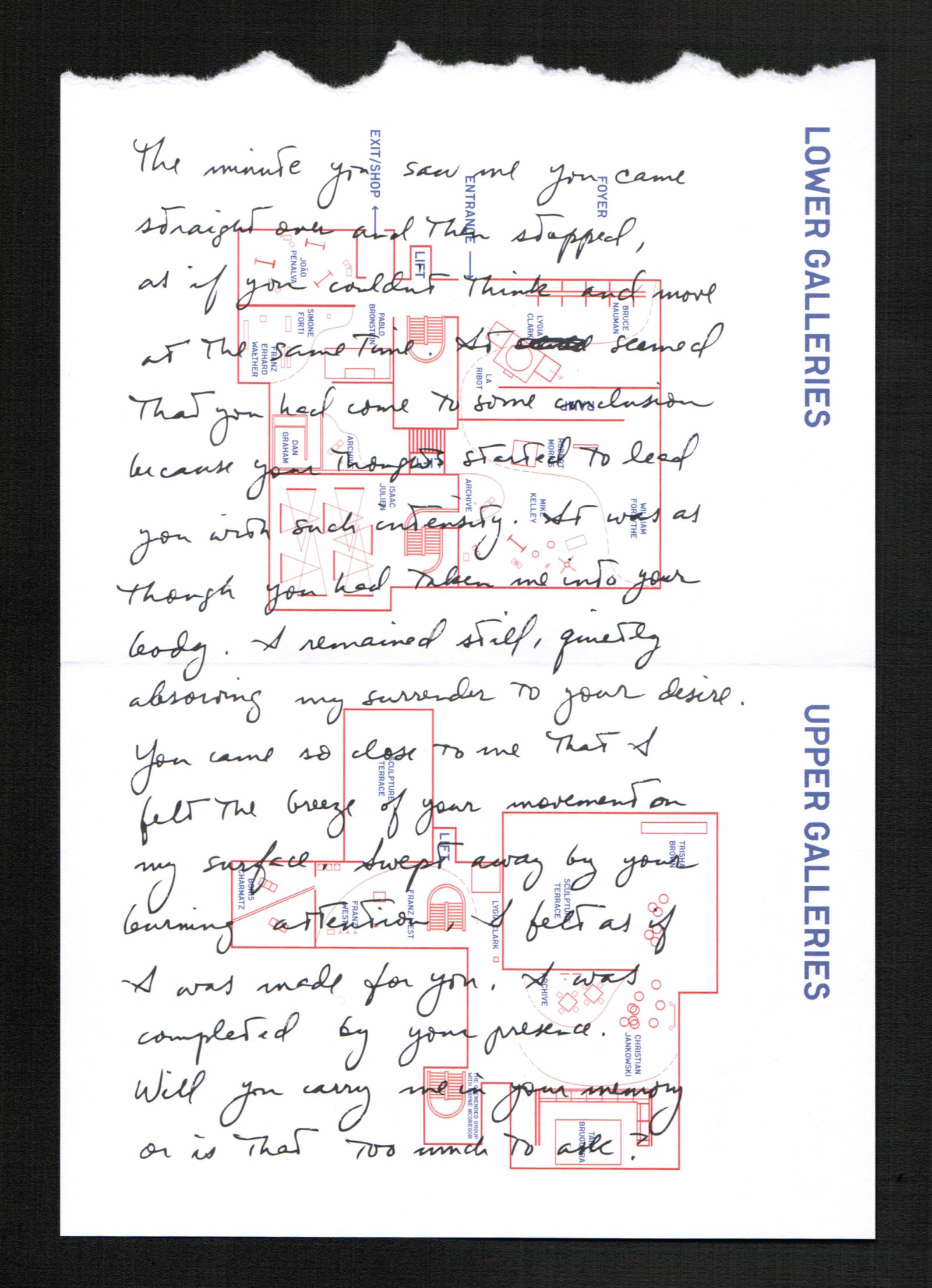

Once conceived as a place for preserving, displaying, and mediating artifacts that represent culture, the museum has shifted its focus significantly in recent decades to orient itself toward its publics. As a provider of services, the museum now sees itself as a site of cultural experience. In this changed economy of space and time, it is no longer only the authors of art who determine the form of an artwork’s encounter with its audience. A major role in planning the choreography of an exhibition is now played by marketing strategists (What is a good lead image?), visitor services (How do I organize maximum visitor flow?), and, above all, museum management. The relatively new and strong interest in theatrical, performance-based, and improvisational art forms may be attributed in part to the fact that exhibitions designed for a wide audience bring with them a certain arbitrariness.

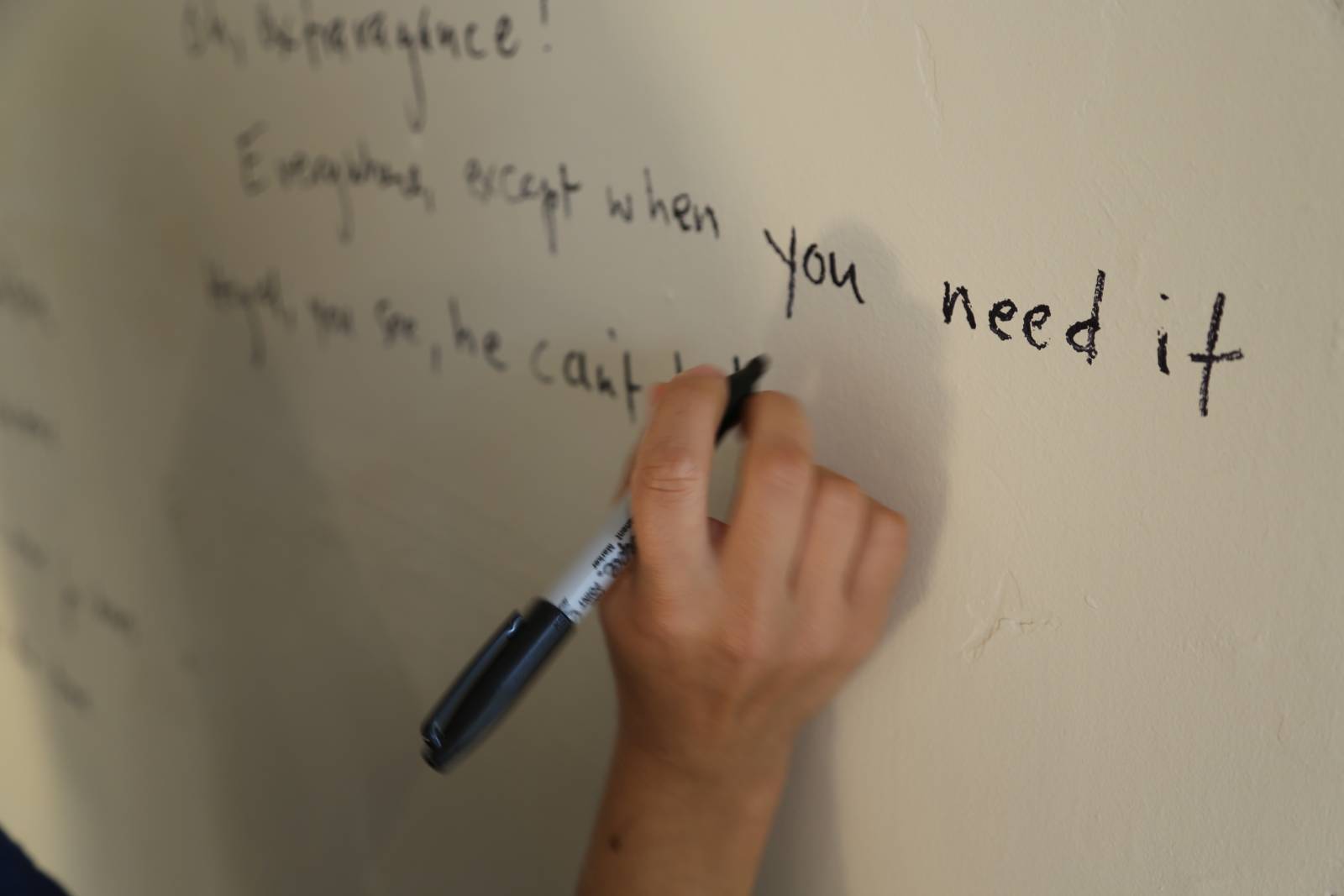

The trend of institutions staging events in their spaces for a mass audience at times stands diametrically opposed to the desire of artists to push the limits of experimentation and creativity. Conceiving their own choreography gives artists the opportunity to regain some control over their work and to arrange their work in space as well as its encounter with the audience according to their own visions. But what if the choreography of performers, which includes the audience, has itself become part of the experience industry? In the summer of 2011 the art collective Grand Openings installed an enormous calendar in the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, publicizing its thirteen-day program of scheduled performances titled Return of the Blogs. The program unfolded as a compendium of performance types that drew from everyday life and art, including restaging of historic works, lecture-performances, dances, songs, rock concerts, and workshops, as well as weddings (both fictional and real) and flash mob–style mass participatory events. The artists exposed themselves in their “museum workspace” to an audience hungry with expectation; in the process, they also confronted their own nonpresence and nonaction.

Translated from the German by Michael Shane Boyle.

For Further Reference

El Lissitzky, Prounenraum (Proun Room), 1923.

Gottfried Schlemmer, Das Triadische Ballett, 1922.

Wiener Gruppe, 1. Literarisches Kabarett, 1958.

Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, 1959.

Simone Forti, Dance Constructions, 1960–61, including Rollers, See-Saw, Huddle, Slant Board, Hangers, Platforms, and Accompaniment for La Monte’s 2 Sounds and La Monte’s 2 Sounds.

Andy Warhol, Dance Diagrams, 1962.

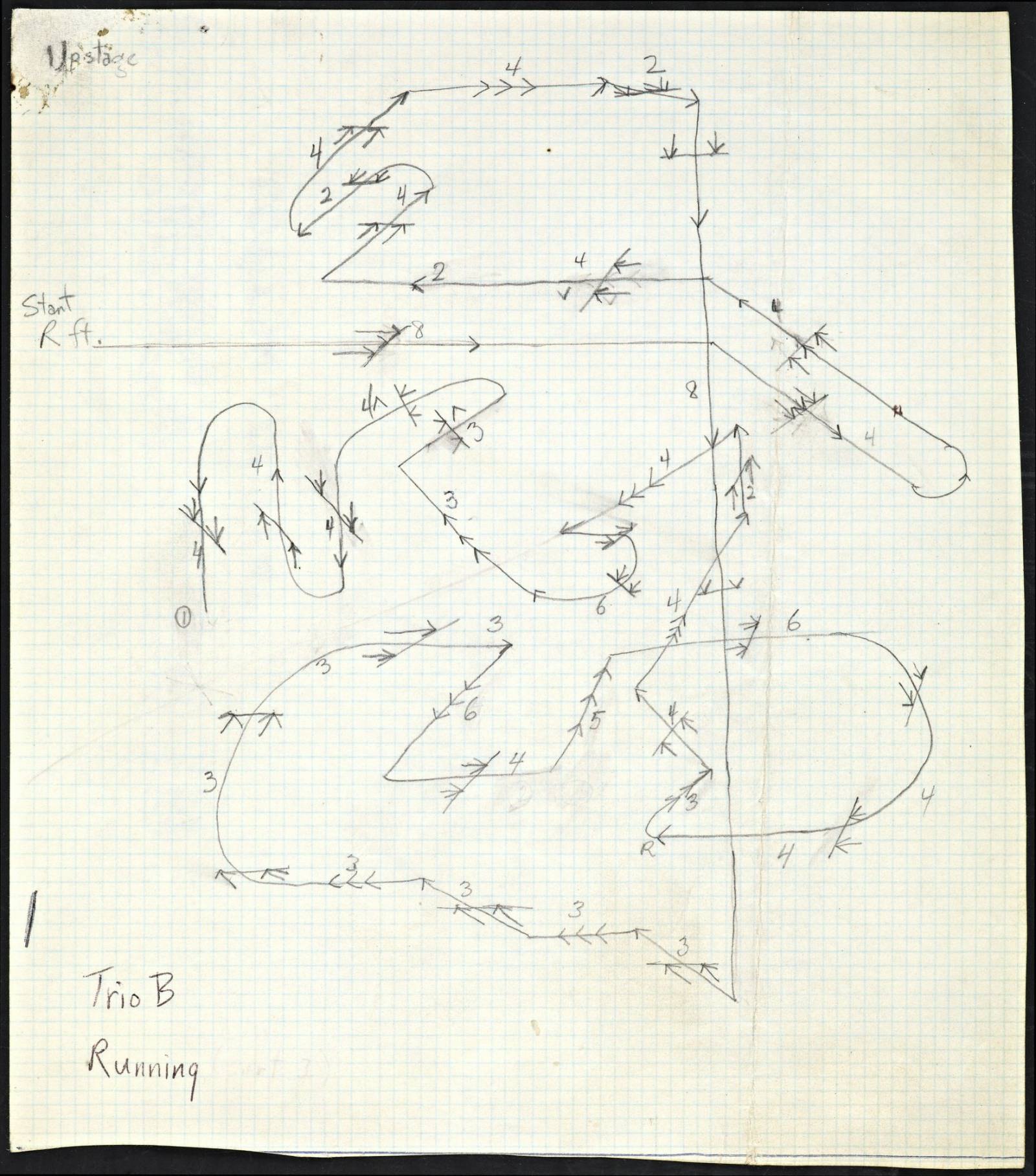

Yvonne Rainer, Trio A, 1966.

Julius Koller, works from the “Anti-Happenings” series, including Tennis, 1963–71, and Ping Pong, 1970–71.

Dan Graham, Body Press, 1970–72.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Tree Dance, 1971.

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights, 1989.