The significance of the term action in relation to art has shifted gradually since the late 1950s and 1960s from connoting straightforward physical action, for example in “action painting,” toward a more charged or political association in the 1970s, relating in part to the idea of activism. However, the term is also used broadly as an adjectival description of art that is non–object based, and has also been used to describe more subtle interventions by artists into the fabric of everyday life, as well as, occasionally, in a deliberately referential way by the current generation of younger artists to invoke the origins of performance art.

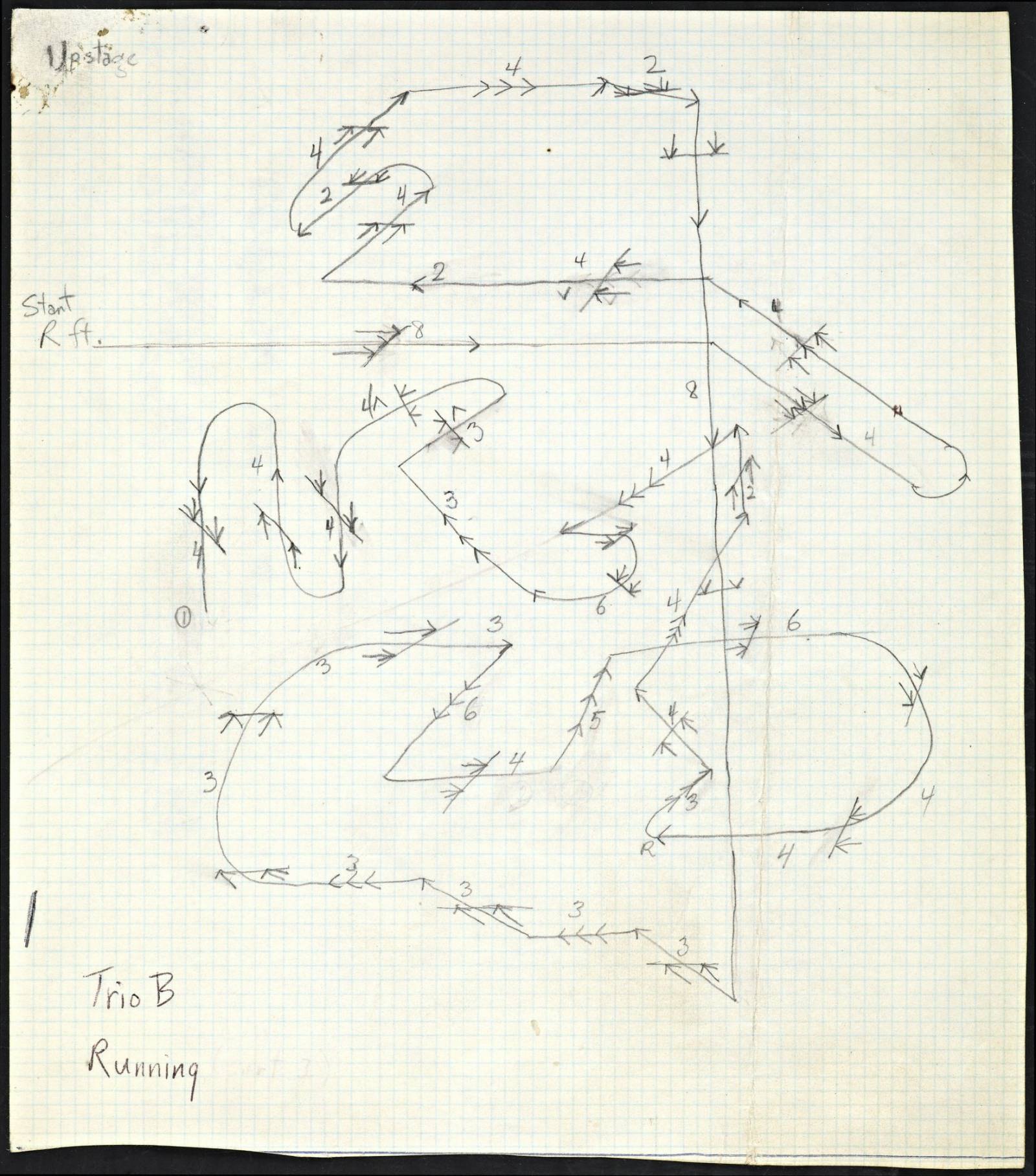

The term action painting, which is arguably the most significant use of the word in visual art history, was initiated by Harold Rosenberg in his essay “The American Action Painters” from 1952. He wrote, “At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act—rather than as a space in which to reproduce, re-design, analyze or ‘express’ an object, actual or imagined.” He claimed that the “picture”—or depictive result—had been replaced by process, the “event.” Action painters such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning made work that manifested the traces of their movements in visible, energetic brush marks, and Allan Kaprow, in “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock” (1958), suggested that it was the actions of Pollock as he made his paintings—captured in photographs and on film by Hans Namuth and others—that would make an impact on the next generation, rather than the paintings themselves.

In the mid- to late 1950s, the Gutai group of artists in Japan began to make “action events” that, in certain ways, related to and expanded upon the look of American action painting. Jiro Yoshihara, one of the key proponents of Gutai, wrote in his manifesto, “Gutai does not alter the material. Gutai imparts life to the material.” Yoshihara explicitly referred to the work of Jackson Pollock in relation to their experiments, although they were also influenced by the practice of Japanese calligraphy, and by the visits of Michel Tàpies and Georges Mathieu to Japan in the late 1950s. The live action events of Gutai artists Shozo Shimamoto and Kazuo Shiraga diverged from US action painting in various ways that were more explicitly theatrical, and designed to be captured on camera: throwing glass bottles full of pigment at the canvas, in the case of the former, or swinging from a rope and painting with his feet in the latter.

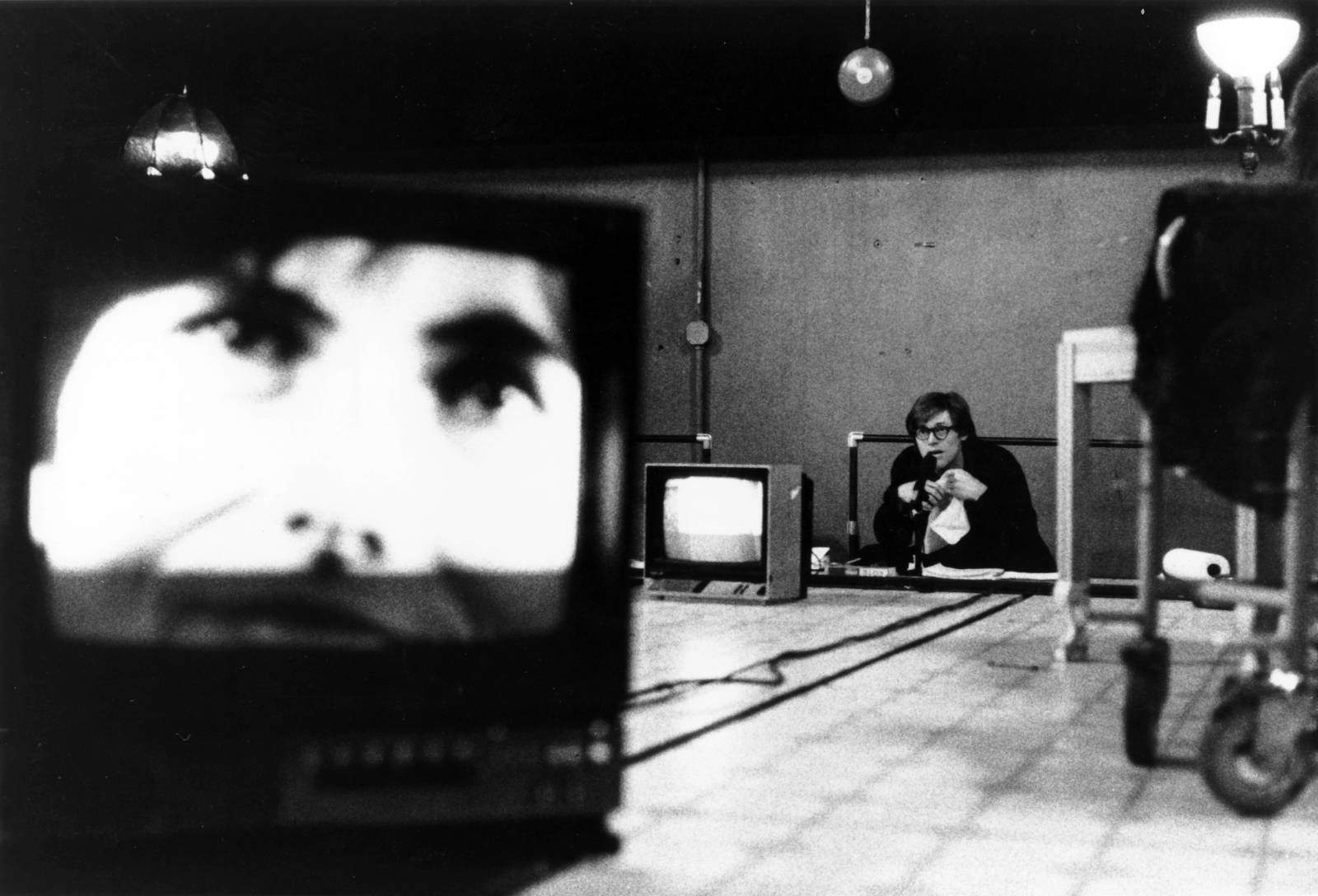

The term action (or aktion in German) was used in parallel by Josef Beuys to describe the live performances that he was making. He made seventy actions between 1963 and 1986. In 1974 he performed one of his most famous actions at the René Block gallery in New York, I Like America and America Likes Me. For Beuys, as this side of his practice came to gain ever-greater significance, the performance action was increasingly related to forms of direct action after the mid-1970s. His ecological-spiritual project of collaborating with local people to begin planting 7,000 oak trees in Kassel was inaugurated in 1982 for Documenta 7.

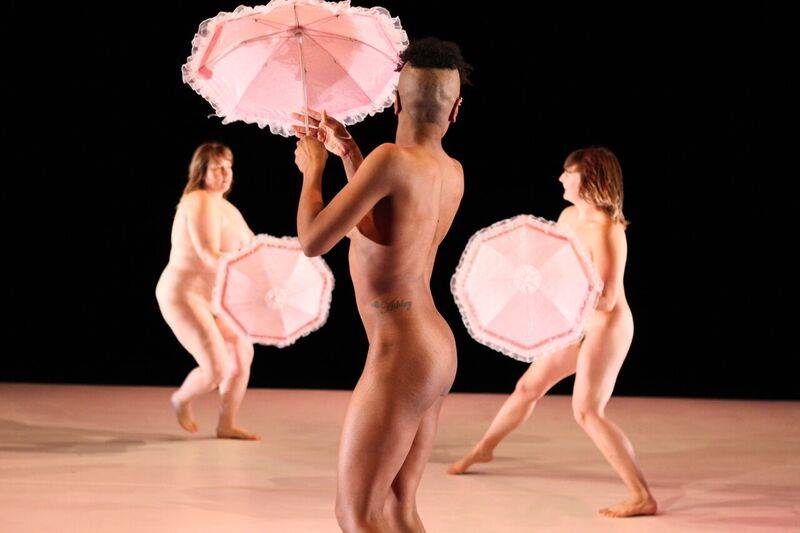

The Vienna Actionists—Hermann Nitsch, Otto Mühl, Günter Brus, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler—became known for a series of highly provocative bodily actions, which they regarded not so much as performances but as a new, living form of painting that included painted bodies, floors, walls, and, in the work of Nitsch primarily, animal carcasses and blood. In the 1960s much of this work was staged solely for the camera, often intended for publication. The Actionists belonged to a generation of Austrians who grew up with the memory of World War II, and their work emerged partly from their reaction against what they saw as the political oppression and social hypocrisy of their country. They saw these actions as a kind of catharsis, freeing the aggressive human instincts that society repressed. As Mühl stated, Actionism was “not only a form of art, but above all an existential attitude.” Emerging from this context, the artist VALIE EXPORT challenged the use of female bodies in both Actionism and mainstream media culture, making works such as Action Pants: Genital Panic (1968), in which she entered an art cinema in Munich wearing leather trousers with the crotch cut out, and roamed among the seated spectators of an experimental film. She also performed a number of actions in the street in collaboration with the Austrian artist Peter Weibel.

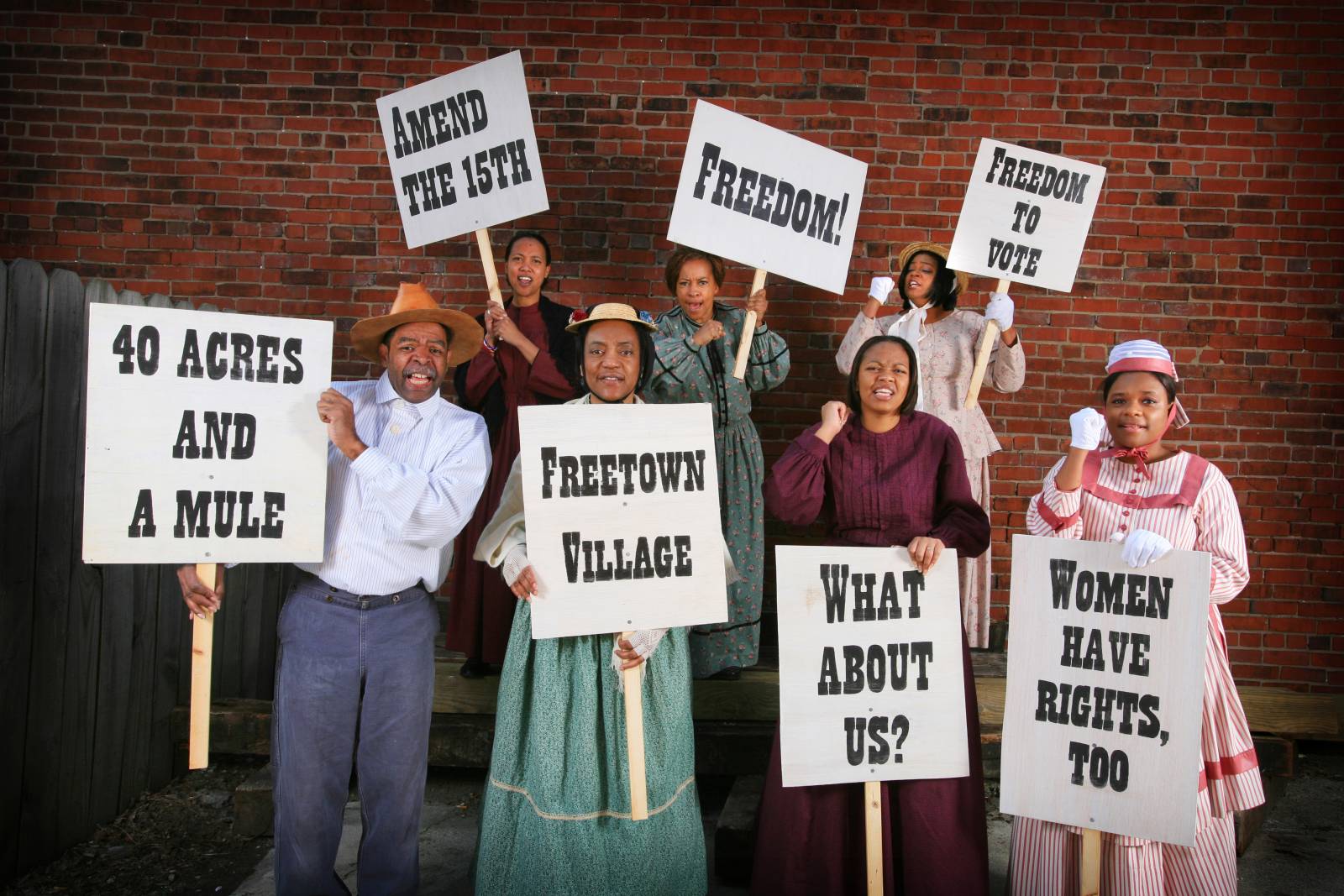

The term action was widely used by performance artists in the 1960s and 1970s. In London, Stuart Brisley recalls it as the favored term among artists to describe performance events, and used it for his own work. Los Angeles–based artists such as Linda Montano and Tom Marioni used the term to describe their live performances in the 1970s, which were often made in storefronts and public spaces. In parallel, artists such as the Collective Actions group in Moscow and KwieKulik in Warsaw used the term action perhaps slightly differently, and poetically, to describe group or collaborative actions performed for each other, as private forms of art-making and experimentation. Jiri Kovanda’s subtle interventions into the everyday activity of the city in Prague, where he lived in the 1970s, could be understood in the same way.

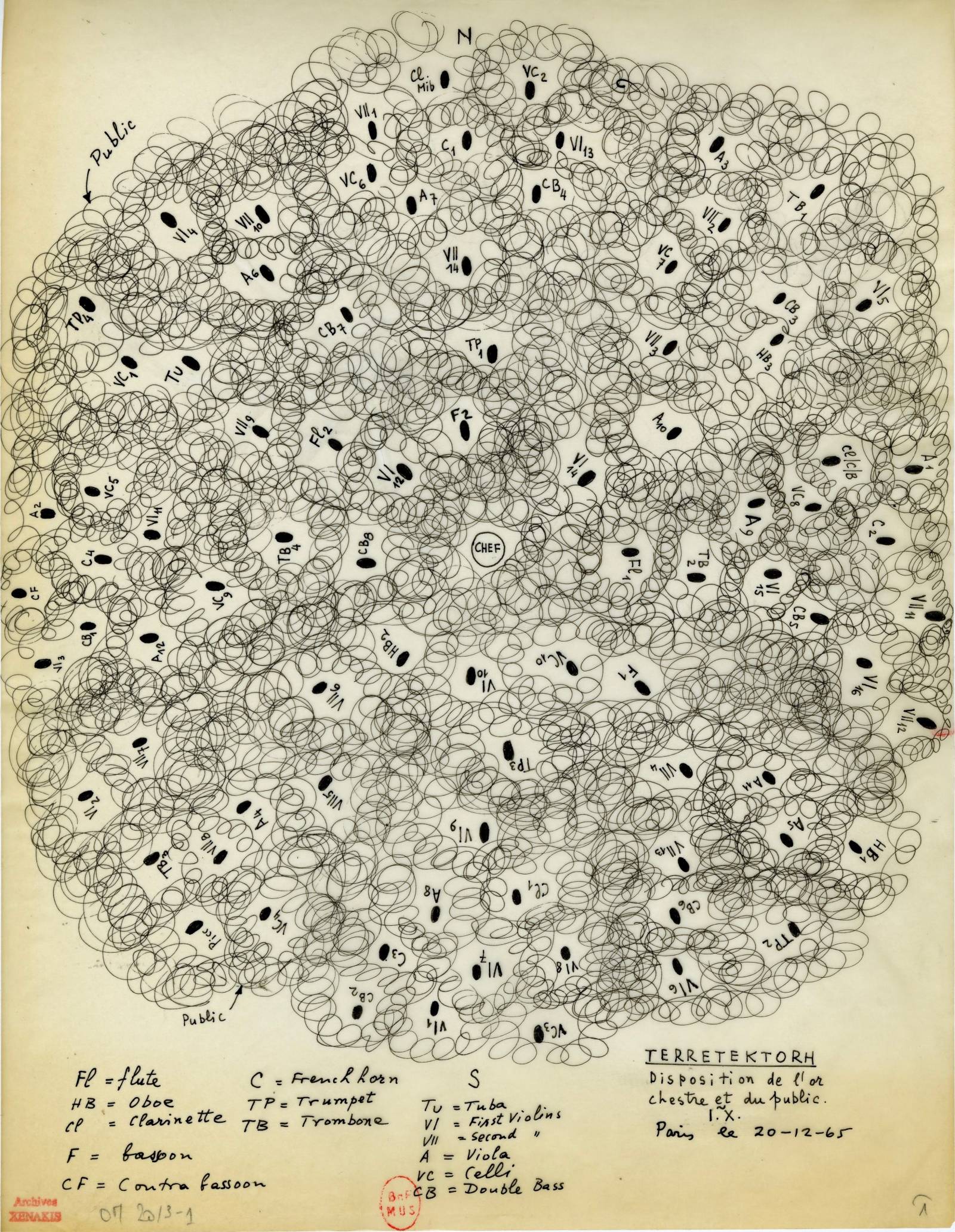

The Filmaktion group in London created performative film events in order to “create a more active, participatory experience of cinema for their viewers, in which they would become alert to the dimensions of the gallery or auditorium around them, and the unfolding event occurring within it.” For a year or more, in 1972–73, Malcolm Le Grice, Annabel Nicolson, William Raban, Gill Eatherley, and others performed together as Filmaktion, though according to Le Grice, “[F]ilmaktion was never a formal group. Filmaktion was the title of an exhibition at the Liverpool Walker Art Gallery in 1972. That was the first time we ever used the term.”

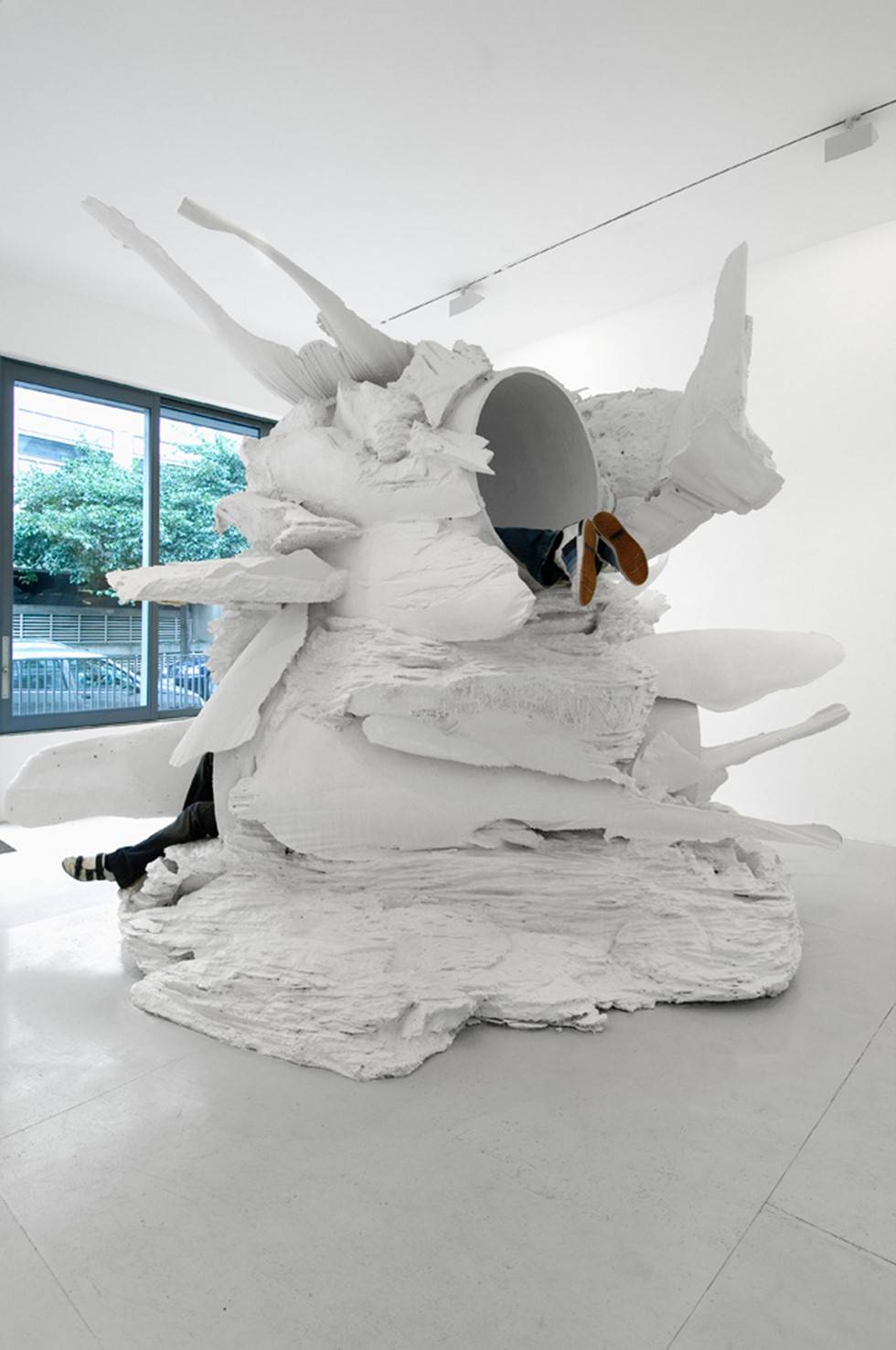

In recent years, the term action has been used more playfully by a younger generation of artists. Swiss artist Roman Signer uses it for his sculptural events, which often involve pyrotechnics: gunpowder and fireworks. The British artist Mark Leckey appropriated it, in part enjoying the word’s fairground-like connotations, for the title of his 2003 performance at Tate Britain, Big Box Statue Action, in which he set Sir Jacob Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel (1940–41) against a speaker-stack sound system. It has also been used variously by museums in titling exhibitions and programs. In 2007, Tate held a two-day performance event titled “Actions and Interruptions” that included Kovanda alongside Mario Garcia Torres and Dora Garcia; the opening program for the Tate Tanks was titled “Art in Action”; a recent exhibition about the legacy of action painting at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm was titled “Explosion! Painting as Action”; and an exhibition at the Migros Museum dealing with the legacies of feminism in 2011 was titled “It’s Time for Action, There’s no Option.”

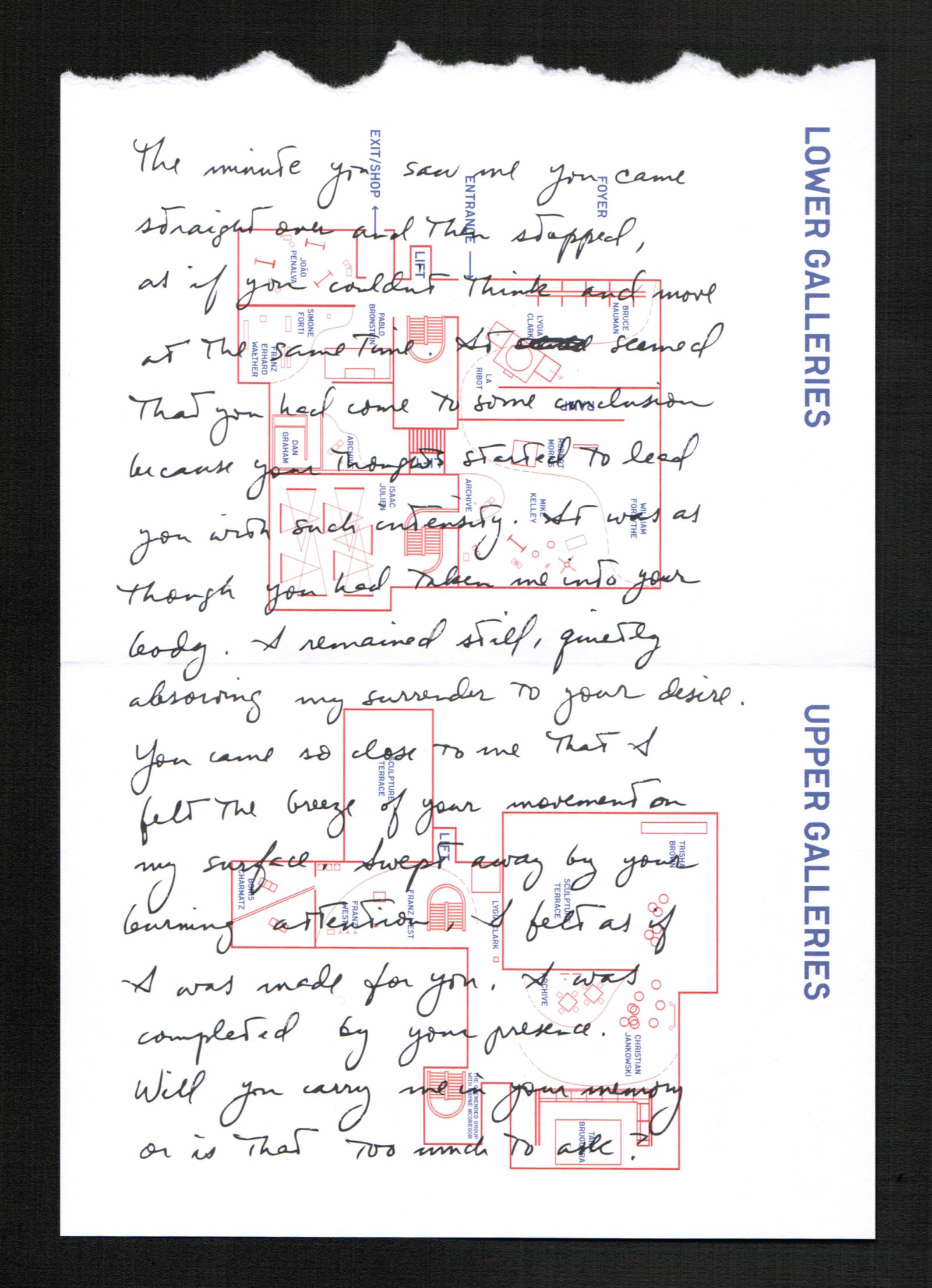

But the term is generally used far less by contemporary artists than it was in the 1960s and ’70s, and, when it is used, it carries a certain knowingness or historical “form.” The word performance is now more common. Nevertheless, sometimes it is used by artists—such as Signer—because “action” seems to be more literally about doing something, and has a sense of being “real” with direct effect, whereas “performance” seems more self-conscious or intentional and is associated, perhaps, with acting and imitation. In her publication with Ana Vujanović, Public Sphere by Performance, Bojana Cvejić attempts to distinguish between the two, citing Richard Schechner: in “doing” versus “showing doing,” the latter is not more fake, but is invested with awareness of the former. But Cvejić asserts that the two should not be separated as a binary opposition. Perhaps we are not at a point beyond the need for marking out “action” as a singular form or material so straightforwardly, and artists are making work in which gestural movement, materials, and the broader setup of audience and architecture are all visible within the frame of art-making. In the exhibition “A Bigger Splash: Painting After Performance,” which I curated at Tate Modern in 2012, I juxtaposed David Hockney’s reflexive approach to figurative painting—his creation of theatrical “sets” for his own flamboyant and camp approach to lived life—and the indexical register of Jackson Pollock’s action painting. While Pollock’s movement across the canvas was understood to be unmediated and raw—an impulse—Hockney’s intricately rendered “splash” might be understood as a performative act of painting that is about “showing doing.” At the other end of the spectrum, the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera has initiated a project titled Arte Util that seeks to push art’s usefulness and capacity to act on real political questions such as immigration and inequality. The question as to whether art—as a representational form—can effect action in any literal sense, to accomplish a purpose, remains open to potentially infinite elaboration and testing within this complex of considerations.