Pauline Oliveros

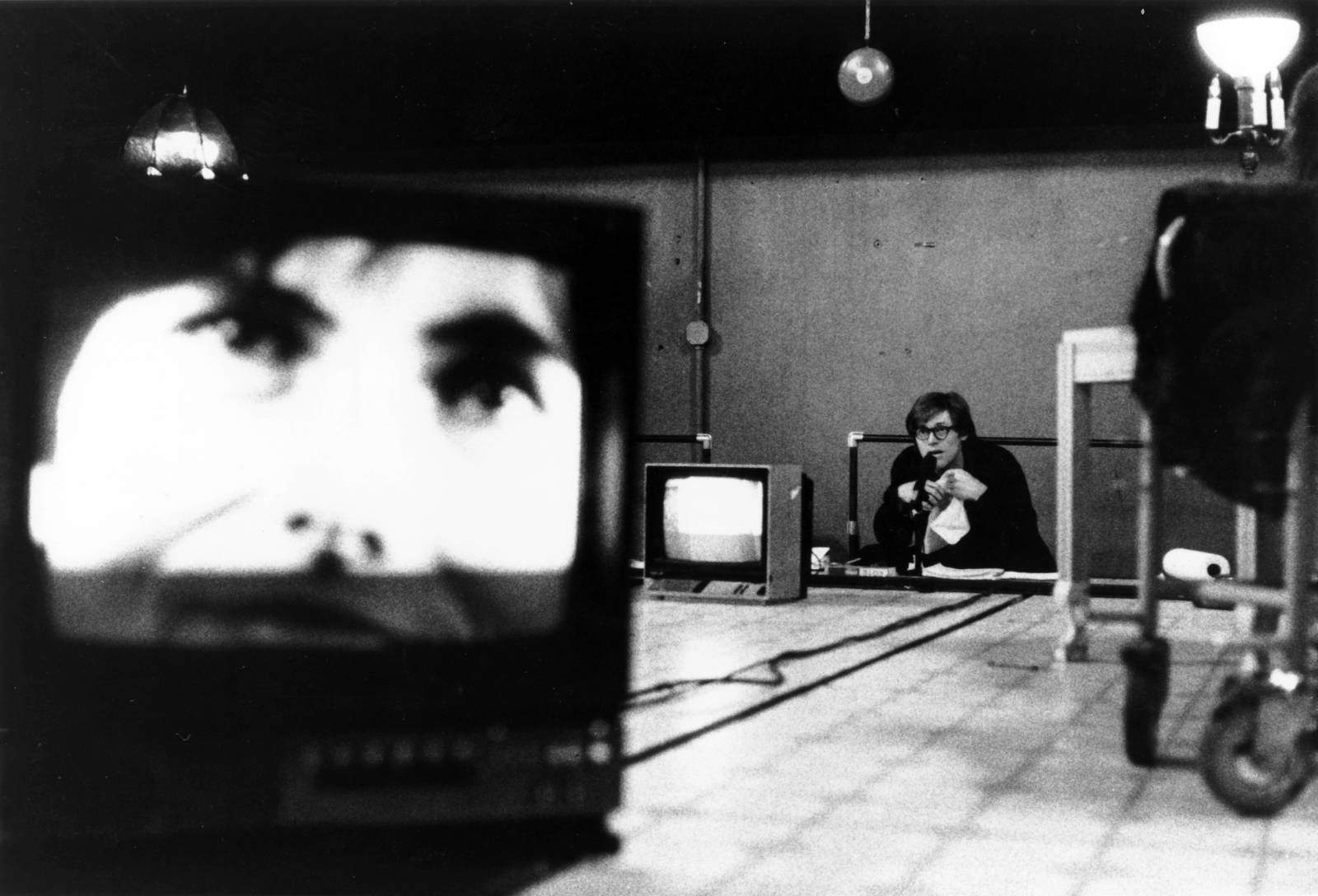

Pauline Oliveros, a pioneering electronic composer and accordionist, developed the theory and practice of “deep listening,” merging music, art, meditation, and technology.

While the duration of most human-generated sounds [is] determined by the information they communicate, musicians and sound artists working at the margins of time have created fascinating works built with sounds of extreme brief- or long-ness, from Iannis Xenakis and Curtis Roads’ micro sounds and punk rock’s energetic brevity to John Cage, Indian ragas, and Justin Bieber’s “U Smile” played at 800%.

—Jeff Thompson

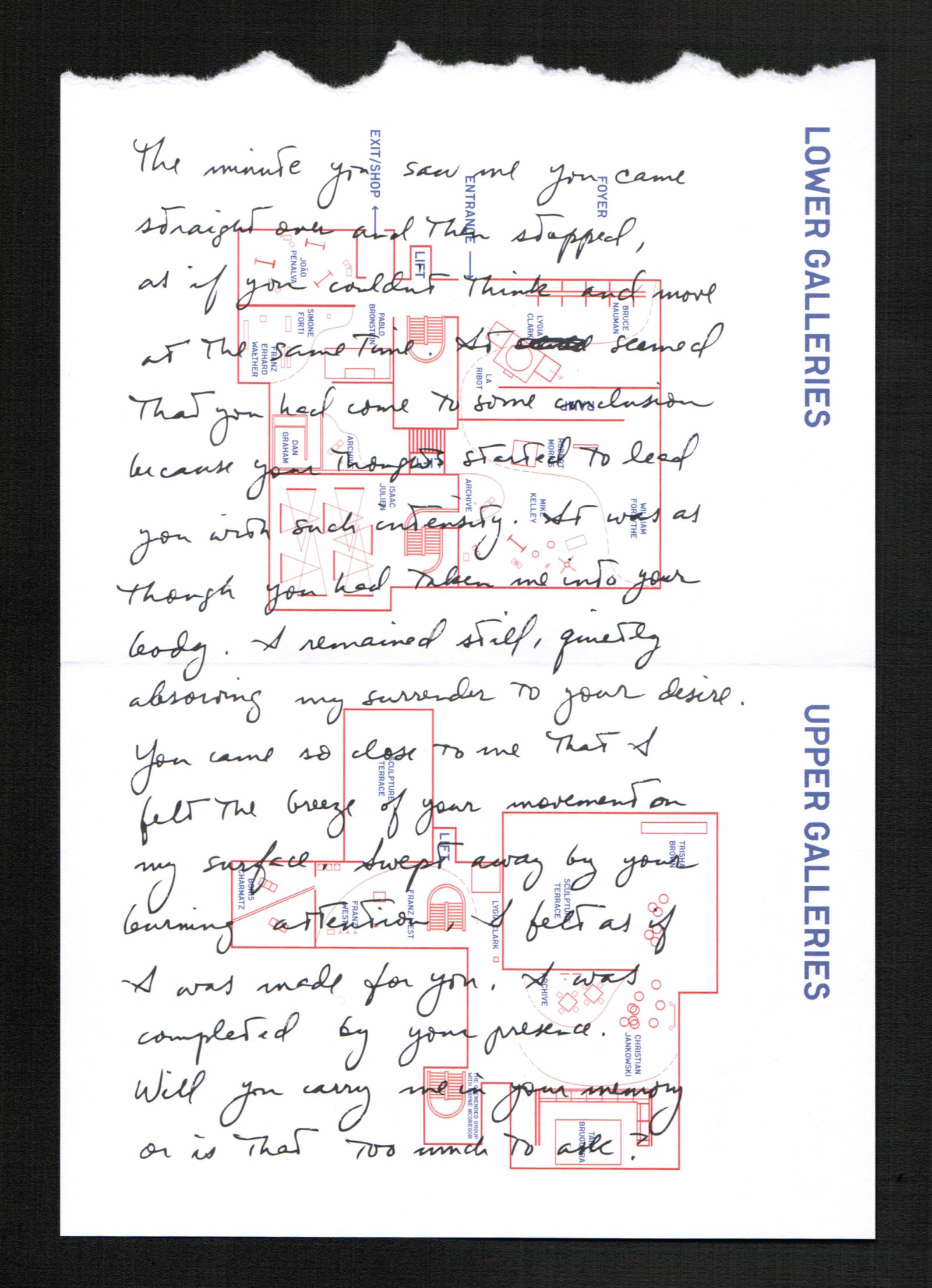

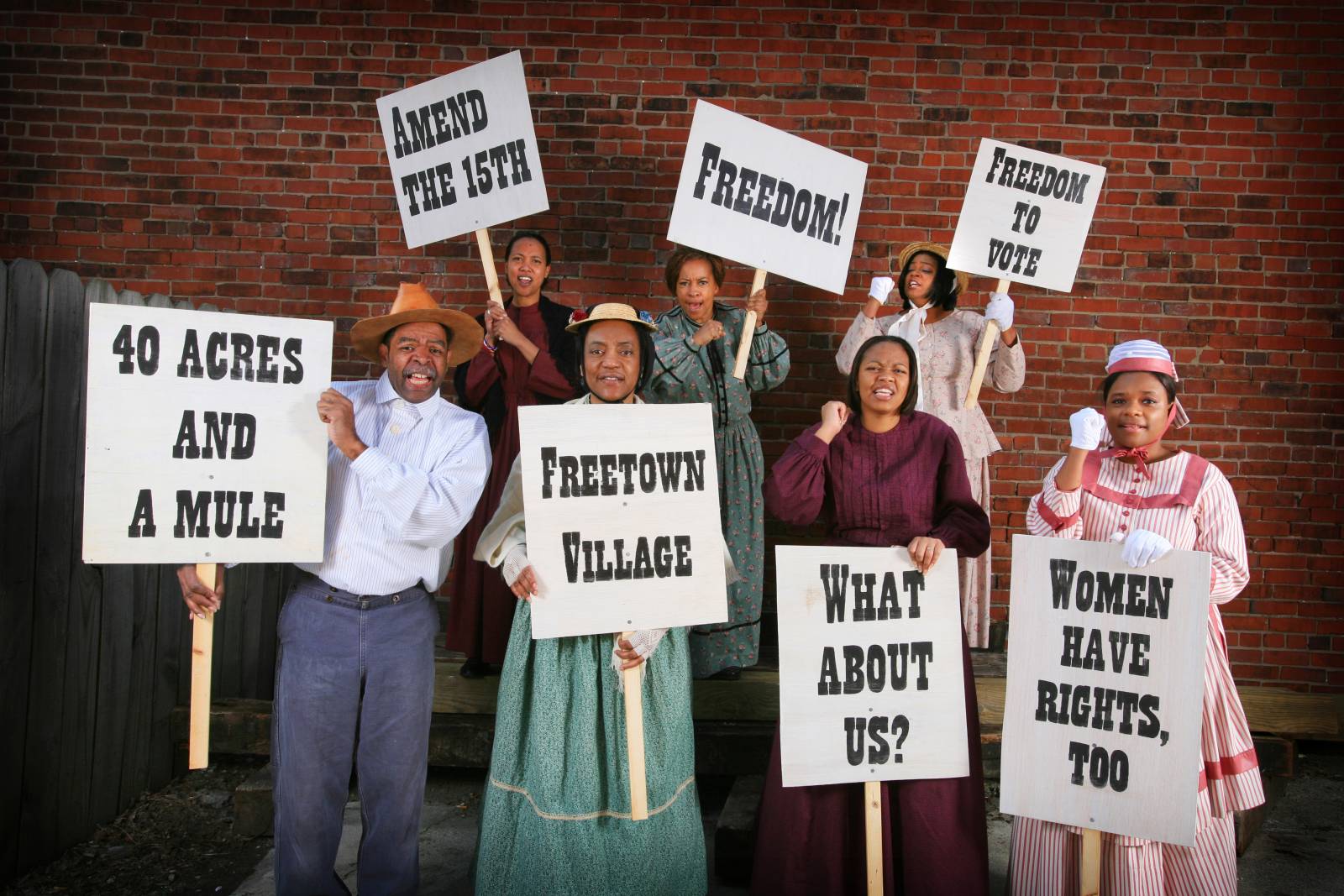

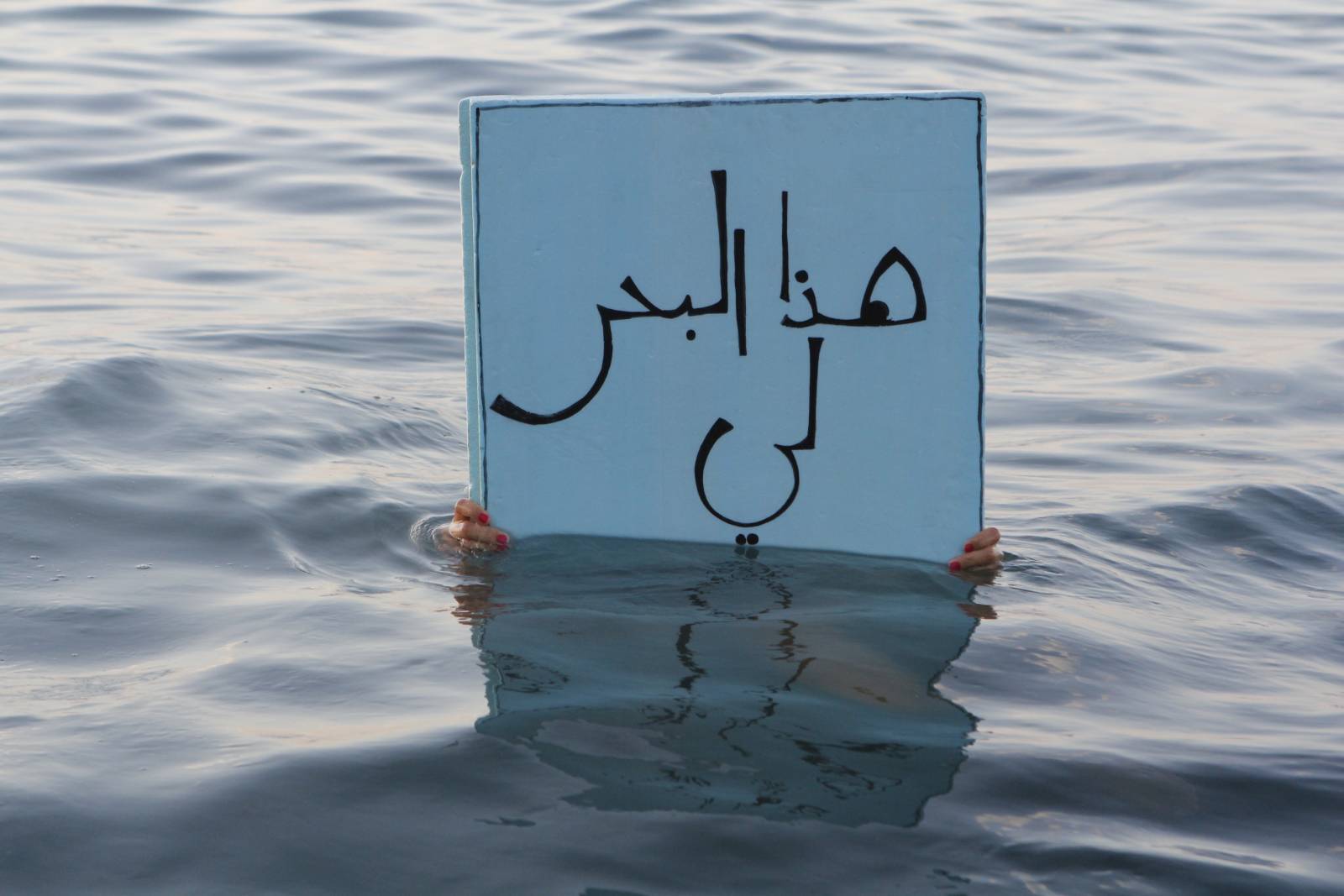

Sound art has emerged from the twentieth century and been identified as “not music”; it has arisen in the transition of music to sound. Extremes of duration have emerged as well in this transition. For example, Max Neuhaus’s sound installation in Times Square, which runs 24-7, has influenced generations of sound artists. Museums are now taking up the call for exhibitions of sound art. The challenge for the curators is how to shift from looking to listening or at least to find a way to balance listening and looking.

My commissioned work The Mystery Beyond Matter (2014) has no beginning and no ending. The players of the Quiet Music Ensemble in Cork, Ireland, like to play “for a long time.” I took them at their word. Duration in The Mystery Beyond Matter is the ongoingness of life. The player enters the flow of sound, whatever it is, by listening until she feels like joining. She plays by listening and stops when she feels like stopping. There is no meter, no counting, no tempo. Rather there is space.

The ensemble of five players may be joined by players listening from other spaces and locations. The sounds from the ensemble players may be sent to other places and returned in another form. Software processing creates changing sound environments, alternating from massively reverberant to barely reverberant little spaces.

Any player may be in any of these environments at any time. The distribution of each player from one environment to another is improvised algorithmically. Thus the player’s responses are to space rather than time.

The term duration became increasingly present for me in the 1960s. The concern with time in my traditionally notated music was to defeat the bar line and to defeat meter. I wanted a more timeless organic flow rather than a regimented beat.

Tempus fugit.

I moved gradually away from conventional notation to improvisation with my acoustic instrument and into tape music. The duration of my electronic music was determined by the medium, that is, tape duration in which the piece recorded was either 7 1/2 inches per second = 30 minutes or 15 inches per second = 15 minutes. Some endings of pieces were rather abrupt because the tape ran out! There was no reason to stop the music other than that the medium could not continue. I was improvising all of my tape and electronic music in “real time.” So my pieces were often as long as the tape. Duration was a problem of the medium.

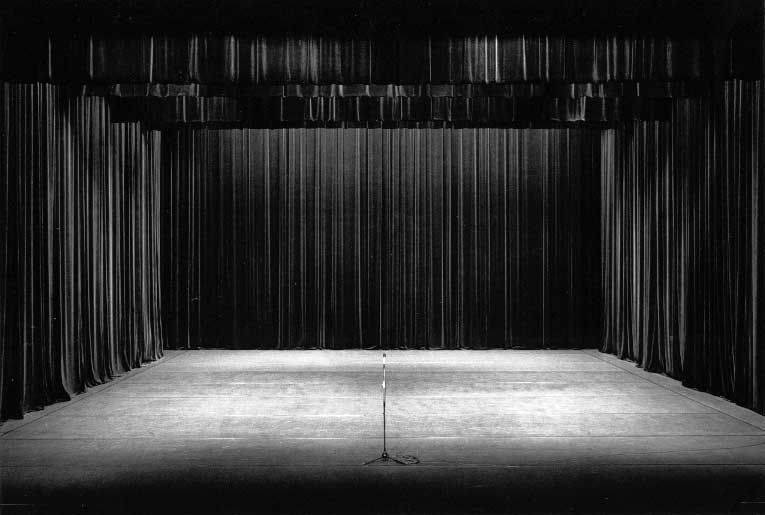

A curator who wanted to program my music asked, “Why don’t you write a short piece?” This prompted me to compose Why Don’t You Write a Short Piece? The performer enters the stage and in one concentrated moment stomps her foot. The lights go out, and she exits. This was a response to the curators who follow the convention of short pieces to fill their programs. The convention seemed to be no longer than twenty minutes. It is no coincidence that 4'33" is a good duration for a museum program!

In 1960 La Monte Young composed Composition 1960 #7, which consists of a B, an F#, a perfect fifth, and the instruction, "To be held for a long time.” The duration of this influential piece and the stasis of its content defied convention.

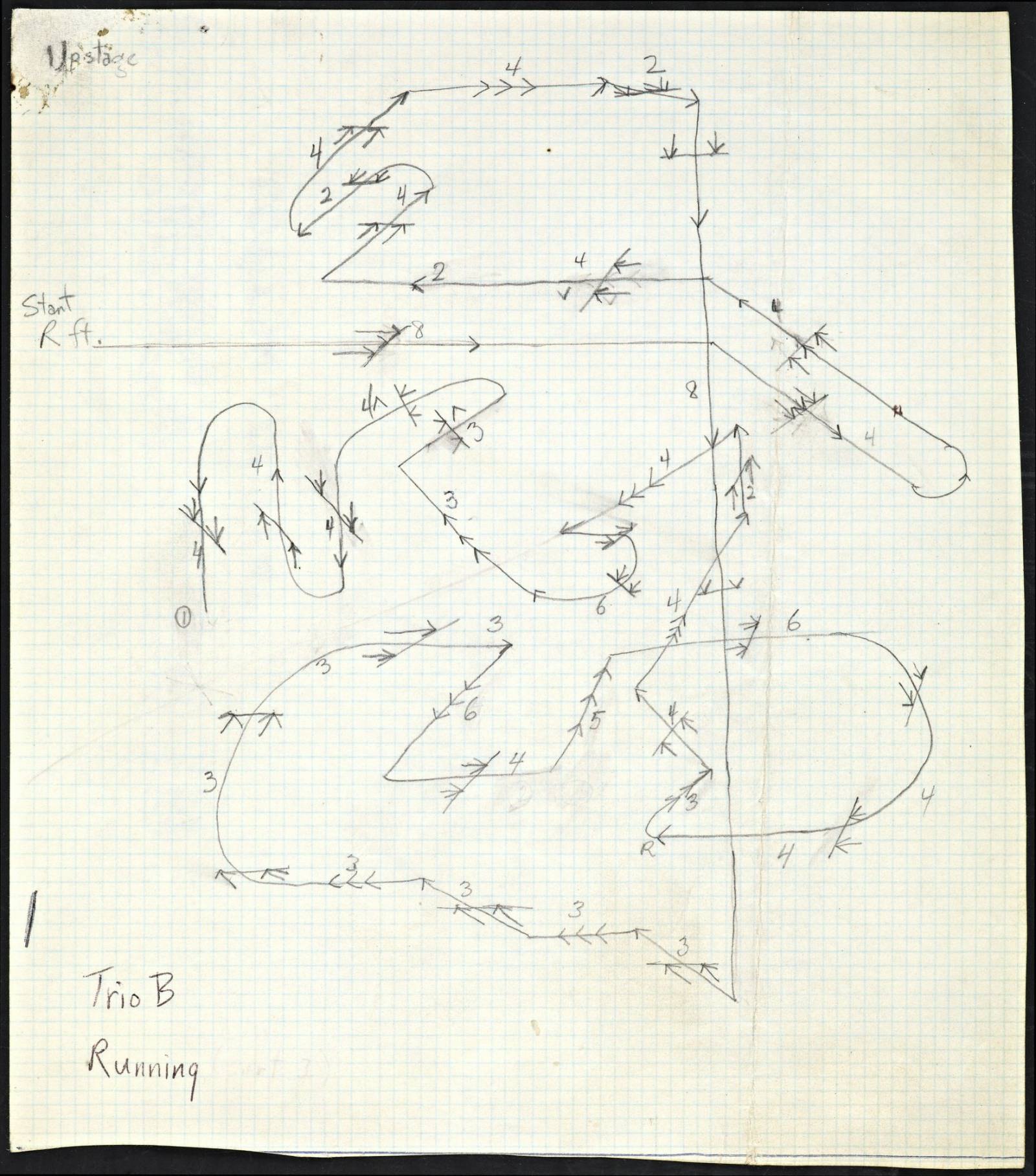

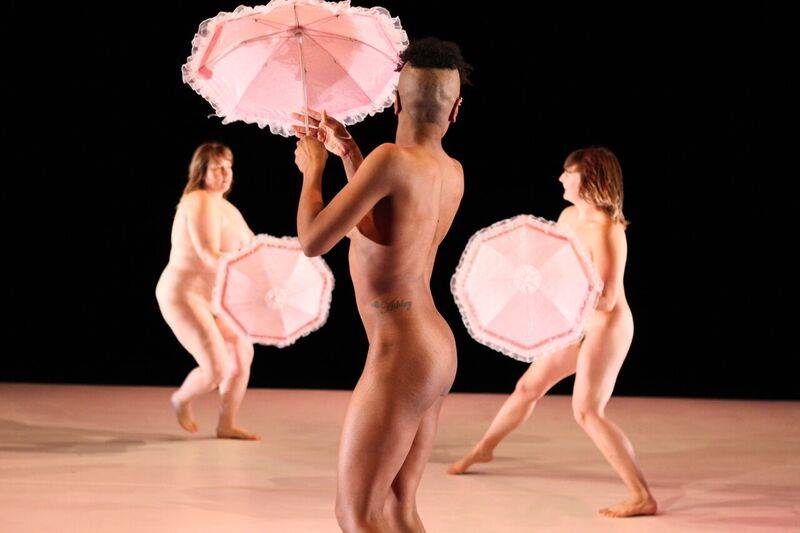

In my Sonic Meditations (1970–74), I shifted to composing the direction of the performer’s attention. Duration was determined by length of breath or by actions or was indeterminate. Musical training was not necessary to perform Sonic Meditations. Instructions were transmitted orally or in prose. Concert venues and audiences were not necessary. The pieces were not intended for curated programs and could be done as solos or with a group. If there was an audience, they were invited to participate.

To end this meditation, I consulted Tao Oracle: The Illuminated New Approach to the I Ching, which is a combination of the Eastern I Ching, the Western tarot, and art.

Hexagram number 32, representing duration, indicates constancy, continuity, endurance, perseverance, maturity, strengthening, stability, and a deep commitment.

For Further Reference

Max Neuhaus, Times Square, originally installed 1977–92, reinstated May 2002. Sound installation, north end of the triangular pedestrian island at Broadway between Forty-Fifth and Forty-Sixth Streets, New York.

“Chopped & Stretched: sounds at the extremes of duration,” curated by Jeff Thompson, Drift Station Gallery, Lincoln, NE, September–October 2011.

“Soundings: A Contemporary Score,” organized by Barbara London with Leora Morinis, Museum of Modern Art, New York, August–November 2013.

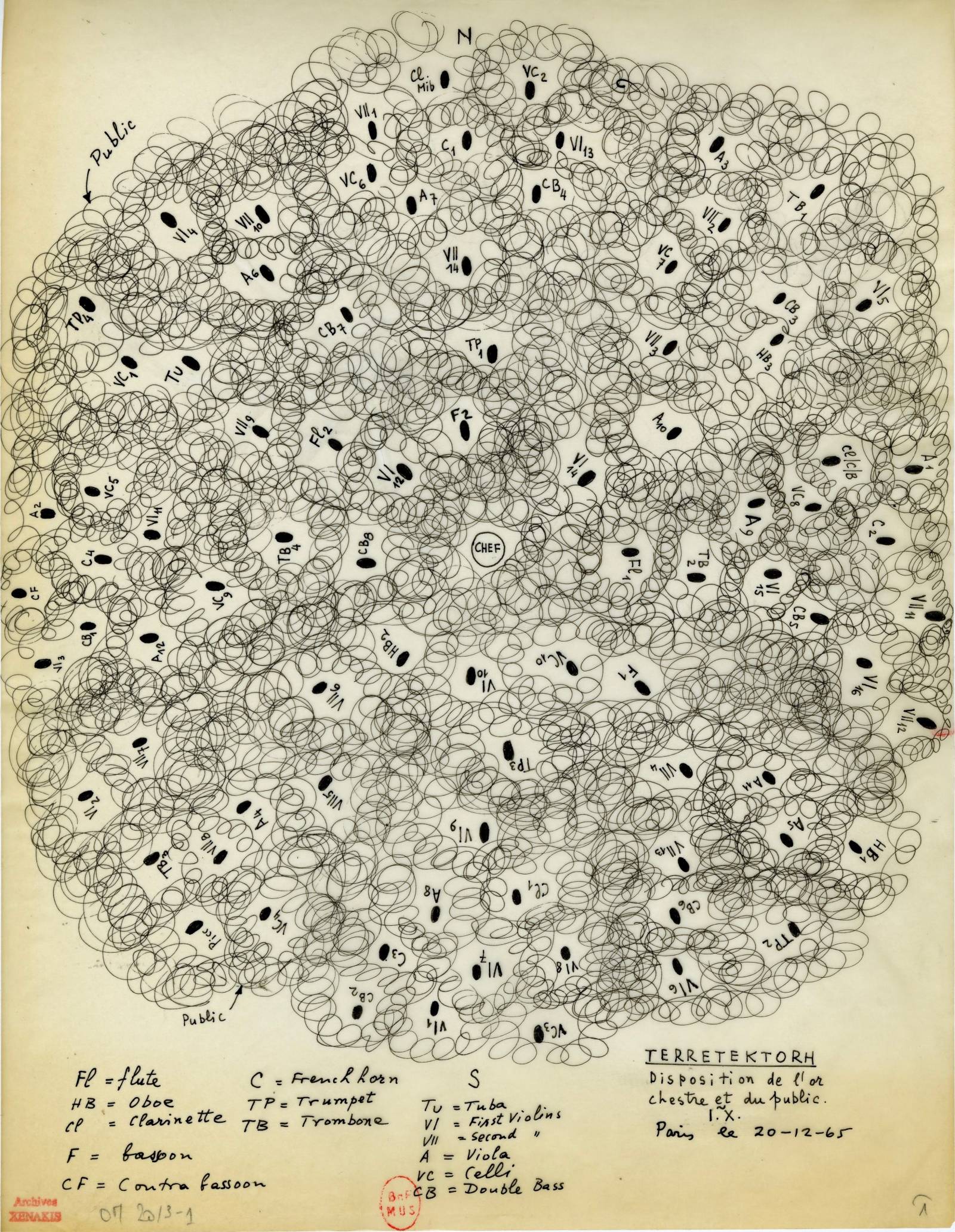

“Iannis Xenakis: Composer, Architect, Visionary,” curated by Sharon Kanach and Carey Lovelace, 2010. Venues: The Drawing Center, New York; Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Curtis Roads, Microsound (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002).

John Cage, 4'33", 1952/1953.

Dhrupad music, an ancient form of Indian classical music.

Justin Bieber, “U Smile,” 2010.

Pauline Oliveros, The Mystery Beyond Matter, 2014.

La Monte Young, Composition 1960 #7, 1960.

Pauline Oliveros, Sonic Meditations (Baltimore: Smith Publications, 1974).