Hotel Modern, Kamp, 2005. Photo: Herman Helle.

See Also

Milo Rau / International Institute of Political Murder, Die letzten Tage der Ceausescus (The last days of the Ceausescus), 2009. Photo: Karl-Bernd Karwasz.

Save texts as PDFs and create your own custom mini-publication to download and print.

Scott Magelssen, associate professor of drama at the University of Washington and director of the Center for Performance Studies, is the author of Simming: Participatory Performance and the Making of Meaning (2014).

Document, along with the adjective documentary, originates in the Latin documentum (“example”) and, like doctor and docent, is rooted in the verb docēre, “to teach.” The Anglo-French document made its way into English in the late Middle Ages. We often regard the term these days as referring to something committed to paper or, more recently, to a digital file (a “doc”) but broadly think of a document as anything that can be considered evidence. In Suzanne Briet’s famous example from her treatise Qu'est-ce que la documentation? (What Is Documentation?, 1951), even an antelope becomes a “document” when captured and displayed in a zoo for study.

In the realm of history and heritage, a document offers evidence that something happened, that it happened in a certain way and involved certain people. As Michel de Certeau put it in The Writing of History (1975), “Historical research grasps every document as the symptom of whatever produced it.”1 But when we look at artistic responses to the past, the strict correspondence between document and evidence unravels. The adjective documentary, modifying a piece of narrative art that we categorize as “nonfiction,” becomes a noun in its own right. The documentary film evidences a historical or cultural phenomenon. Documentaries make truth, and they change us in big and small ways. In our house, we’ve changed the way we eat ever since, quite by accident, we viewed the documentaries King Corn (2007) and Food, Inc. (2008), adjacent in our Netflix queue, in the same week. The fictional film Zero Dark Thirty (2012), based on the real events of the hunt for Osama bin Laden, was passed over by the Oscars because of aggressive lobbying critical of its depictions of torture as an enhanced interrogation technique.

“Documentaries,” however, comprise all sorts of art and performance in heritage and cultural attractions. In 2010 Hotel Modern’s Kamp, staged in an enormous scale model of Auschwitz populated by three thousand puppets at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn, documented the death camp for audiences. Visitors to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, document the lives of people during those same events with their own bodies as they vicariously play out the story assigned in their passports at the outset of their visit. Other attractions have picked up on this latter form of embodied documentary. Those who participate in the Caminata Nocturna at an eco park in Mexico simulate an illegal US-Mexico border crossing to document the lives of the thousands of undocumented workers who do it each year for real. In 2010 forty-five actors from the Reykjavík City Theatre documented their country’s near economic collapse with a staged reading of the entire 2,250-page Icelandic government report on the financial crisis. Meanwhile, Colm Toíbín’s play based on his novella The Testament of Mary (2012) gives us the mother of Jesus in the last years of her life. Mary does not believe many of the stories about her son, and she irritates his followers with her ambivalence about endorsing their version of events for the record.

The mid- and late twentieth century saw renewed efforts at accuracy at heritage sites, with the positivist understanding that by researching the documents enough we could “get the past right.” This coincided with social history’s movement to uncover and tell the stories of those underrepresented in traditional histories, the problem in this case being that these populations didn’t leave documents as traditionally understood. For the last couple of centuries, history as a discipline has had strategies for dealing with these gaps. Roland Barthes coined the term reality effect, in an eponymous essay, to describe narrative structures imposed by the present that filled the interstices between that which we can reasonably say we know about past events.2 Barthes offers the imaginative account of the last hours of Charlotte Corday before her execution in Jules Michelet’s book Women of the French Revolution (1855). Georg Büchner was at work at a similar project earlier in that century when he interwove backroom imaginings with verbatim public speeches by Danton and Robespierre in his play Dantons Tod (Danton’s Death, 1835) to make sense of the Reign of Terror—in a manner that anticipated the works of theater of testimony playwrights like Emily Mann (Execution of Justice, 1986), Anna Deavere Smith (Fires in the Mirror, 1992, and Twilight, 1994) and Moises Kaufman (Gross Indecency, 1997, and The Laramie Project, 2000). Perhaps closest to Büchner, David Hare’s Stuff Happens (2004) mixes verbatim public speeches and backroom imaginings to make sense of the reign of the “war on terror” that led to the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

As artists, performers, audiences, and participants permit themselves to depart from, play with, and interrogate the documentary record, newer discourses reimagine what “accuracy” means as a performative and/or historiographic goal. Scholars in concord with these approaches include Diana Taylor (The Archive and the Repertoire, 2003), Rebecca Schneider (Performing Remains, 2011), and Anthony Jackson and Jenny Kidd (Performing Heritage, 2012). The playwright Suzan-Lori Parks reminds us that where there are silences in the historical record, theater can be an “incubator for the creation of historical events,” adding, “as in the case of artificial insemination, the baby is no less human.”3

The drive to document the past with performing arts like film, theater, and dance, or visual arts like photography, or to challenge existing documents with these same practices, will no doubt continue as long as there is a past—and a present from which to remember, interrogate, and bear witness to it. Certain questions should remain at the forefront as we assess these practices: we need not question the degree to which the documentary adequately or successfully achieves “accuracy” but rather we should ask who is being remembered and how is it being done. Who stands to gain by the documentary practices? What interests are at stake? How are audiences’ and participants’ own memories and values activated and/or challenged, and how do these memories and values inform the documentary practice? And to what extent will artistic practices in the present become new legitimate documents for the record?

Michel de Certeau, The Writing of History, trans. Tom Conley (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), 11. ↩

Roland Barthes, “The Reality Effect” (1968), in The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill & Wang, 1986), 141–48. ↩

Suzan-Lori Parks, “Possession” (1994), in The America Play and Other Works (New York: Theater Communications Group, 1995), 5. ↩

Zero Dark Thirty, directed by Kathryn Bigelow, 2012.

Hotel Modern, Kamp, 2005. Performed at St. Ann’s Warehouse, Brooklyn, 2010.

Alan Rickman, My Name is Rachel Corrie, 2005.

Colm Toíbín, The Testament of Mary, 2013.

Emily Mann, Execution of Justice, 1986.

Anna Deavere Smith, Fires in the Mirror, 1992, and Twilight, 1994.

Moisés Kaufman, Gross Indecency, 1997, and The Laramie Project, 2000.

David Hare, Stuff Happens, 2004.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DC.

Caminata Nocturna, Parque EcoAlberto, Mexico.

Hotel Modern, Kamp, 2005. Photo: Herman Helle.

Milo Rau / International Institute of Political Murder, Die letzten Tage der Ceausescus (The last days of the Ceausescus), 2009. Photo: Karl-Bernd Karwasz.

Paul Chan, Waiting for Godot in New Orleans, 2007. Photo: Frank Aymami. Courtesy of Creative Time.

Andrea Fraser, Projection, 2008. Still from a 2-channel HD video projection installation. © Andrea Fraser. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler.

David Levine, Bystanders, 2015. Installation view, Gallery TPW, Toronto. Performer: William Ellis. Photo: Guntar Kravis.

VALIE EXPORT, TAPP und TASTKINO (Tap and touch cinema), 1968. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Bildrecht, Vienna. Photo © Werner Schulz.

My Barbarian (Malik Gaines, Jade Gordon, and Alexandro Segade), Broke People’s Baroque Peoples’ Theater, 2010. Courtesy of Alexandro Segade.

Richard Maxwell, Neutral Hero, 2012. The Kitchen, New York. From left: Janet Coleman, Bob Feldman, Lakpa Bhutia, Andie Springer, Jean Ann Garrish. Photo © Paula Court.

Miguel Gutierrez and Tarek Halaby in Gutierrez's Last Meadow, 2009. Dance Theater Workshop, New York, September 2009. Photo © Ian Douglas.

Mac Wellman, Muazzez, 2014. Performer: Steve Mellor. Chocolate Factory Theater, Queens, New York (a co-presentation with PS 122). Photo: Brian Rogers.

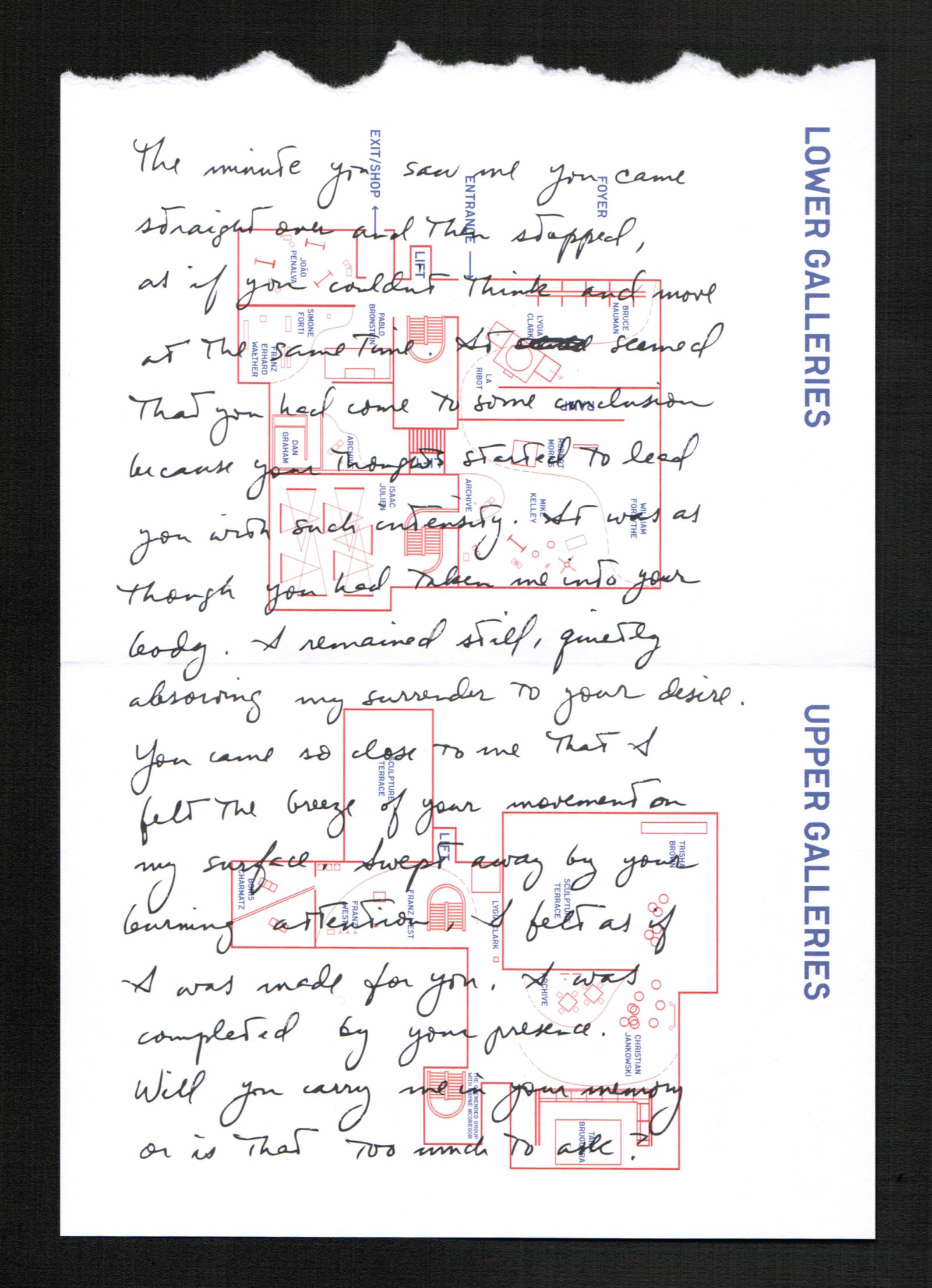

Janine Antoni, Yours Truly, 2010. Ink on paper, 5 7/8 x 8 1/2”. © Janine Antoni. Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

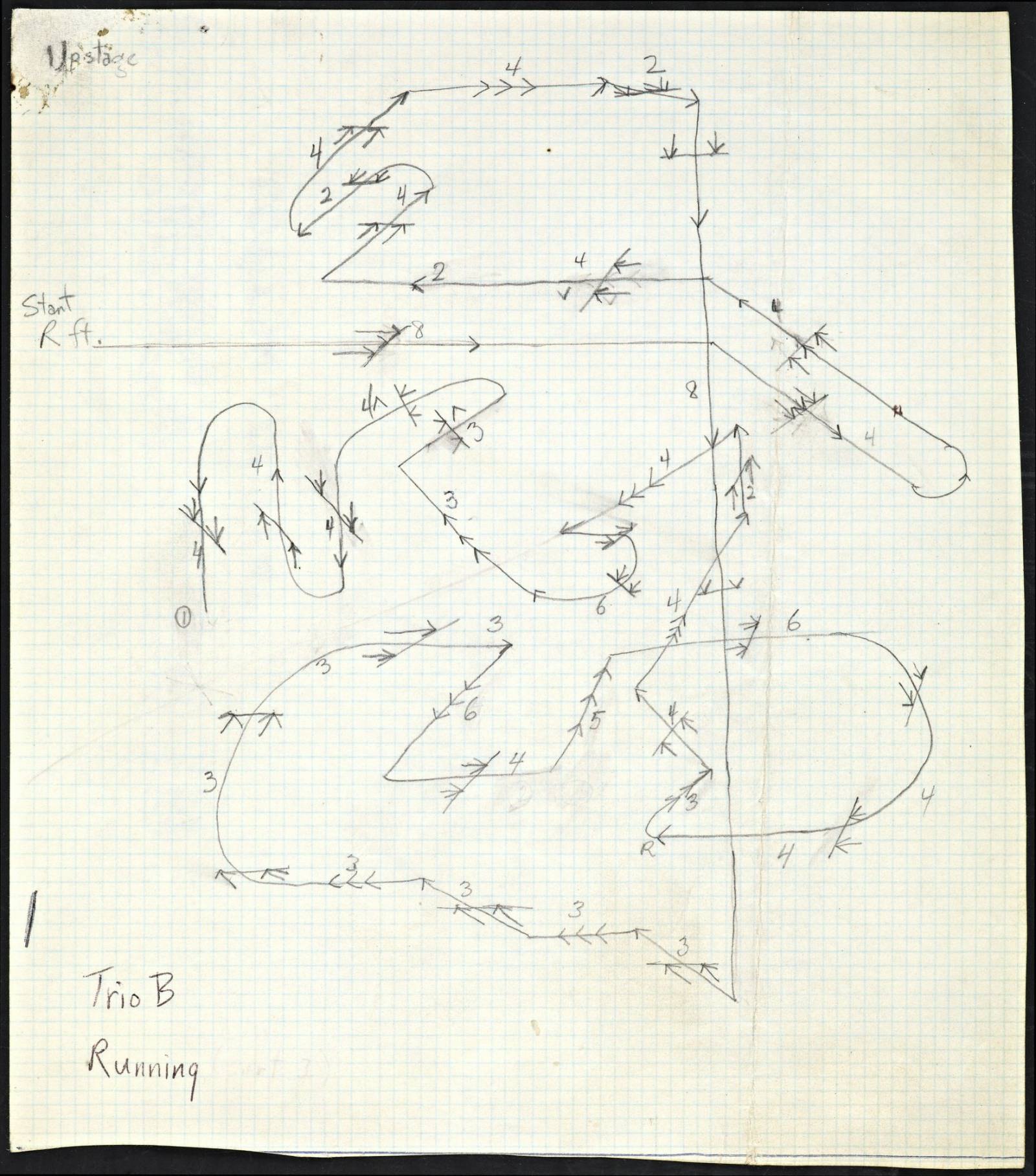

Yvonne Rainer, score for “Trio B: Running,” from The Mind Is a Muscle, 1966–68. Graphite and ink on paper, 8 5/16 x 7 5/16". The Getty Research Institute. © Yvonne Rainer.

Susan Leigh Foster, The Ballerina’s Phallic Pointe, 2011, a performed lecture in the series Susan Foster! Susan Foster! Three Performed Lectures, produced by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage and performed at the Philadelphia Live Arts Studio, 2011. Photo: Jorge Cousineau.

Opening performance of the exhibition “Trisha Brown: So That the Audience Does Not Know Whether I Have Stopped Dancing,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2008. Brown improvises movements across a large piece of paper on the Medtronic Gallery floor, holding charcoal and pastel between her fingers and toes, drawing extemporarily. Photo: Gene Pittman for Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

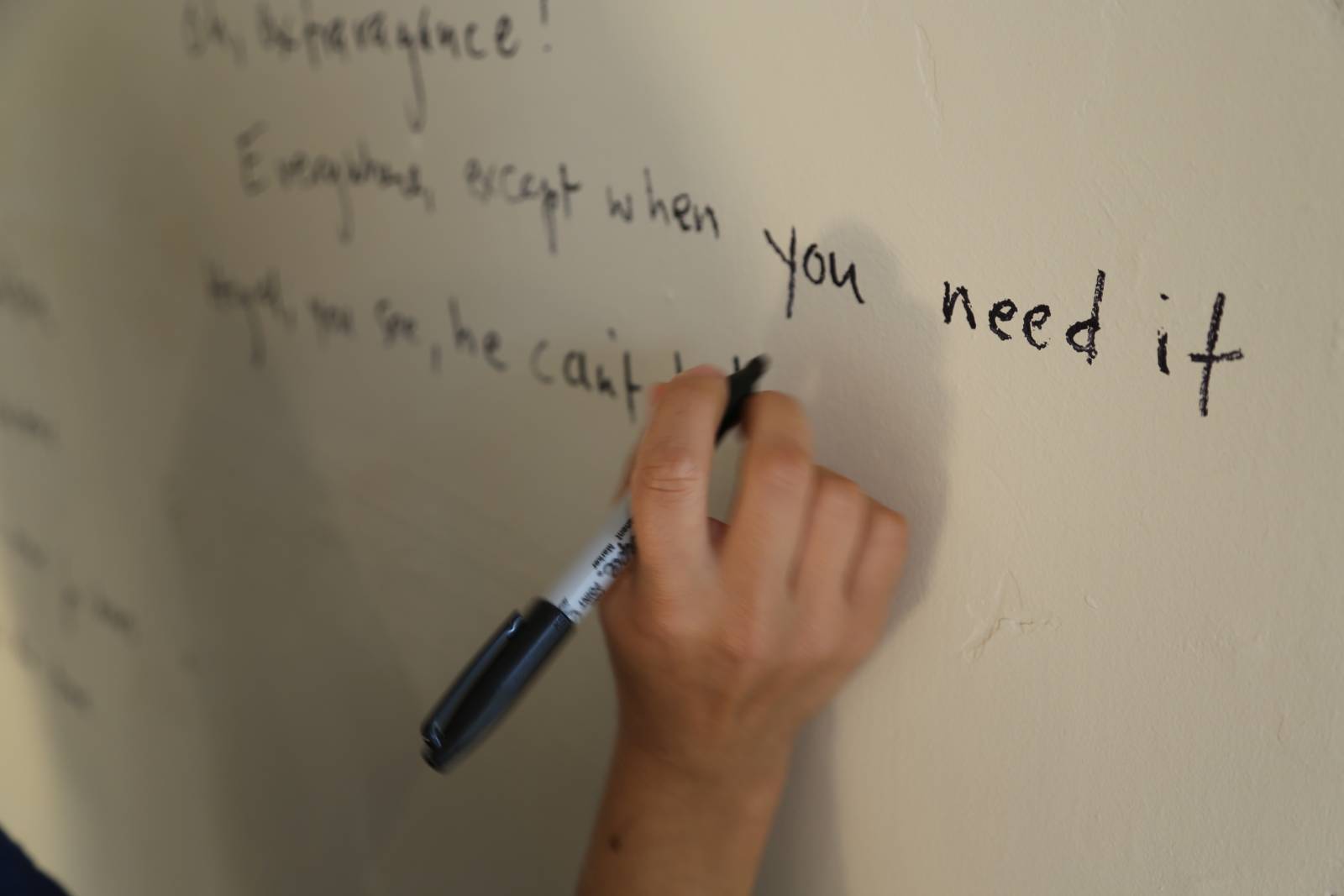

Allora & Calzadilla, Sediments Sentiments (Figures of Speech), 2007. Mixed-media installation with live performance and pre-recorded sound track, dimensions variable. © Allora & Calzadilla. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

Martha Rosler, Meta-Monumental Garage Sale, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

Lucinda Childs, Pastime (1963), 2012, performed by Childs at Danspace as part of Platform 2012: "Judson Now." Photo © Ian Douglas.

Siobhan Davies and Helka Kaski, Manual, 2013. Photo © Alan Dimmick. Courtesy of Glasgow Life.

“Performance Now,” curated by RoseLee Goldberg. Installation view, Kraków Theatrical Reminiscences, Poland, 2014. Photo: Michal Ramus. Courtesy of Independent Curators International (ICI).

Steve Paxton, Intravenous Lecture (1970), 2012. Performed by Stephen Petronio with Nicholas Sciscione. Part of Platform 2012: “Judson Now,” curated by Judy Hussie-Taylor, Danspace, New York. Photo © Ian Douglas.

Installation view, “Dance Works I: Merce Cunningham—Robert Raschenberg,” curated by Darsie Alexander at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2011. Photo: Gene Pittman for Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Chief Dalcour and the Serenity Peace Birds in “Public Practice: An Anti-Violence Community Ceremony,” curated by Delaney Martin and Claire Tancons for New Orleans Airlift, October 25, 2014. Photo: Josh Brasted.

Ain Gordon and David Gordon, The Family Business, premiered 1993. Performers: David Gordon, Ain Gordon, Valda Setterfield. Photo: Andrew Lichtenstein. Courtesy of the photographer and Pick Up Performance Co(s).

Hotel Modern, Kamp, 2005. Photo: Herman Helle.

Janine Antoni, Anna Halprin, and Stephen Petronio, Rope Dance, 2015. Photo © Hugo Glendinning. Courtesy of the artists and The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia.

Sarah Michelson, Devotion Study #1—The American Dancer, 2012 Whitney Biennial, February 26, 2012. Photo © Paula Court. Performers: Eleanor Hullihan and Nicole Mannarino.

Ralph Lemon, How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere?, 2009. Archival print from original film. © Ralph Lemon.

Pope.L, The Great White Way, 22 miles, 9 years, 1 street (Whitney version), 2001. © Pope.L. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York. Photo: Lydia Grey.

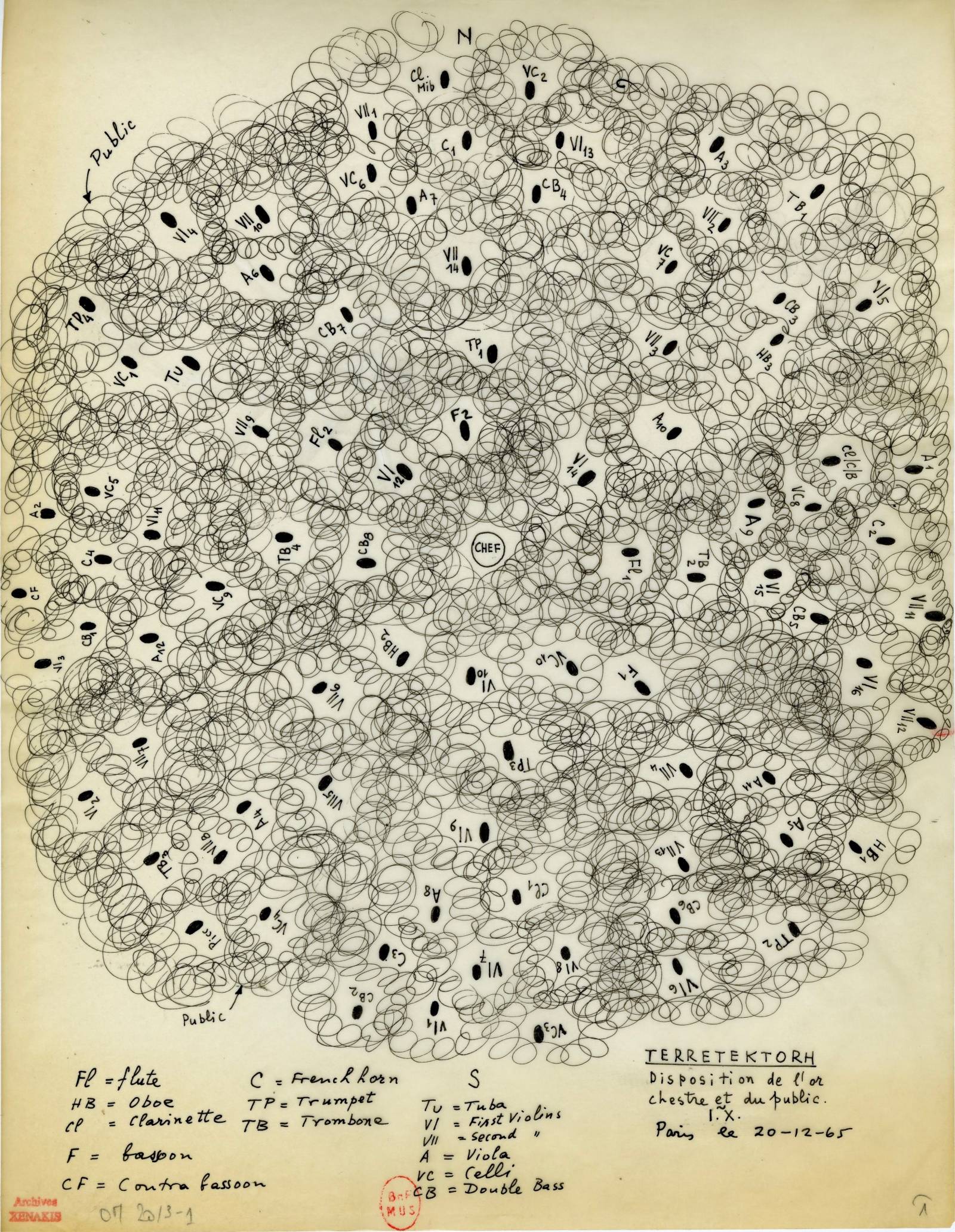

Iannis Xenakis, Terretektorh, Distribution of Musicians, 1965. Collection famille Xenakis. Courtesy of the Iannis Xenakis Archives. © Iannis Xenakis.

Lisa Bielawa, Chance Encounter, premiered 2007. Co-conceived with Susan Narucki. Photo: Corey Brennan, 2010, Rome.

Claudia La Rocco, 173-177 [or, Facebook Is Inescapable], 2013. Headlands Center for the Arts. Courtesy of José Carlos Teixeira.

Pina Bausch and the Tanztheater Wuppertal, Palermo, Palermo, Brooklyn Academy of Music, 1991. Photo: Maarten Vanden Abeele.

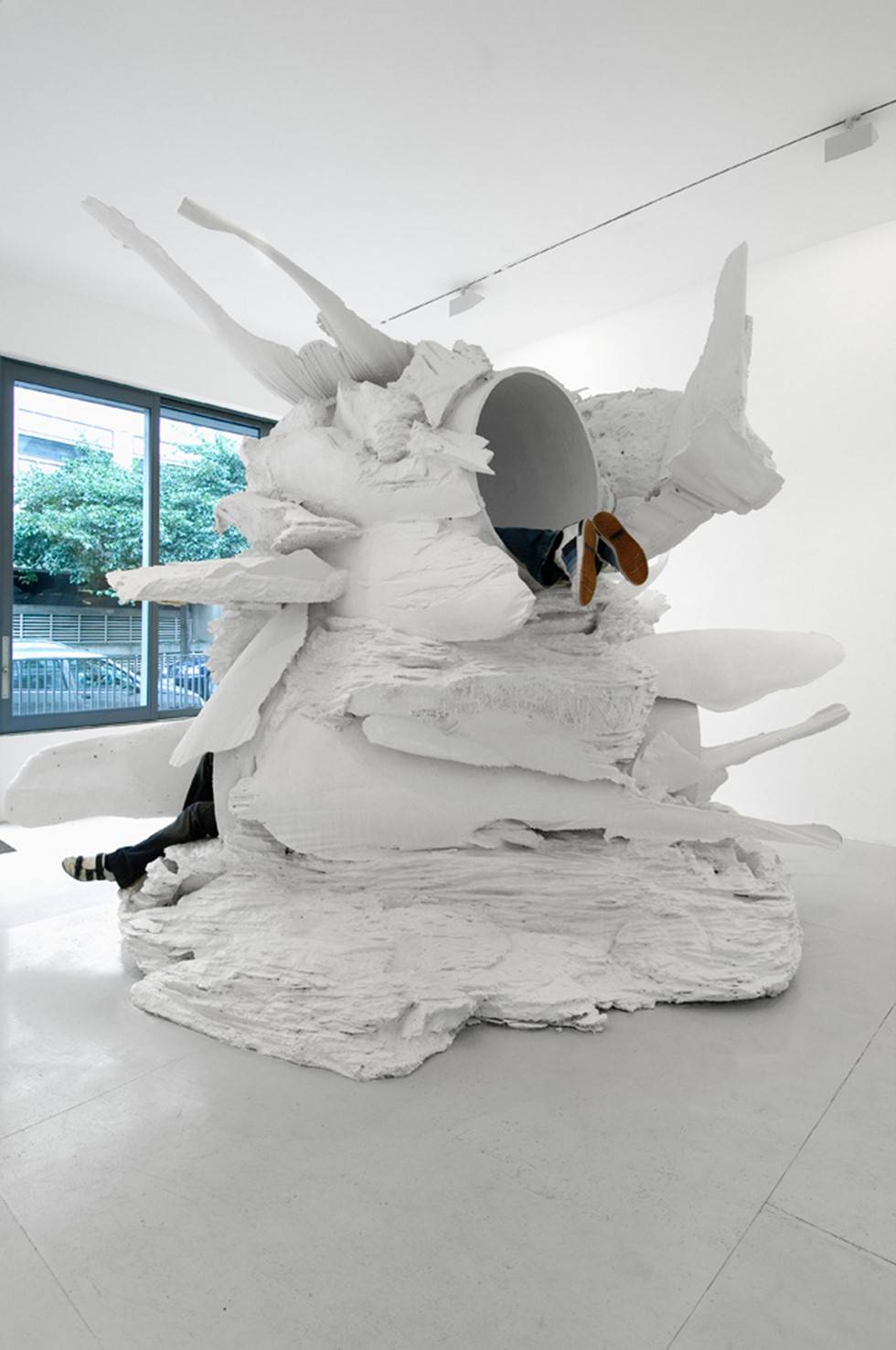

Tomás Saraceno, Observatory, Air-Port-City, 2008. In “Psycho Buildings: Artists Take on Architecture,” curated by Ralph Rugoff, Hayward Gallery, London. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

Christian Marclay, Chalkboard, 2010, paint and chalk, 210 x 1,045 inches. Installation view, “Christian Marclay: Festival,” 2010, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Collection of the artist; courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Christian Marclay.

Steven Schick at the “Peacock” in the Paul Dresher Ensemble Production of Schick Machine, 2009, by Paul Dresher, Steven Schick, and Rinde Eckert. Mondavi Center, UC Davis, Davis, CA. Photo: Cheung Chi Wai.

Ralph Lemon in An All Day Event: The End, part of Platform 2012: “Parallels.” Danspace, New York. Photo © Ian Douglas.

Installation view, “Allison Smith: Rudiments of Fife & Drum,” The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT. Photo: Chad Kleitsch. Courtesy of The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

David Levine, Habit, 2012. Installation view, Luminato Festival, Toronto, 2011. Photo: David Levine.

Meredith Monk, Shards (1969–73), 2012. Part of Platform 2012: “Judson Now,” curated by Judy Hussie-Taylor, Danspace, New York. Photo © Ian Douglas.

Berlin, Bonanza, 2006. A documentary project focusing on Bonanza, Colorado, population 7. © Berlin. berlinberlin.be.

Gob Squad, Kitchen (You’ve Never Had It So Good), 2007. Photo © David Baltzer / bildbuehne.de / Agentur Zenit Berlin.

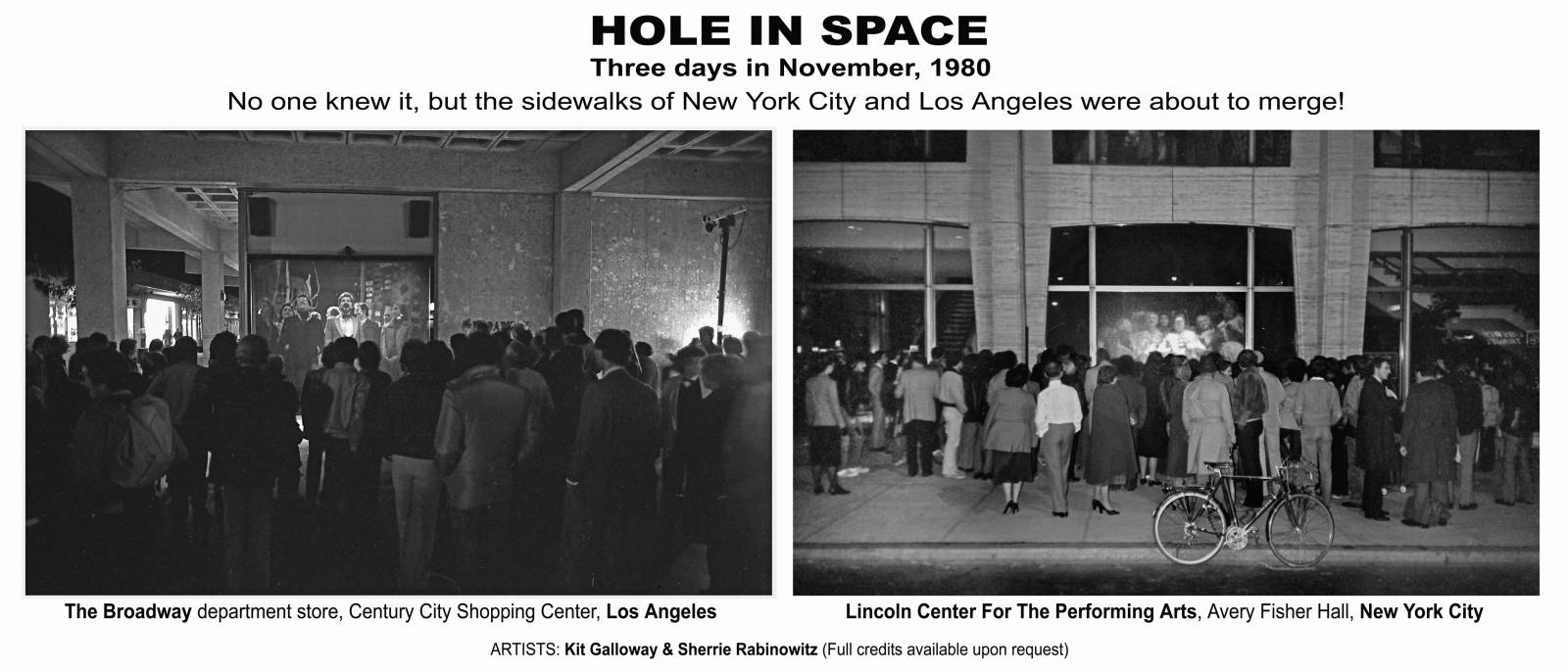

Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz, Hole in Space, 1980. On screens in front of Lincoln Center and The Broadway department store in Los Angeles, passersby could see and talk to their counterparts on the opposite coast, and many “reunions” were quickly set up, in this early example of video conferencing. Courtesy of the Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway Archives.

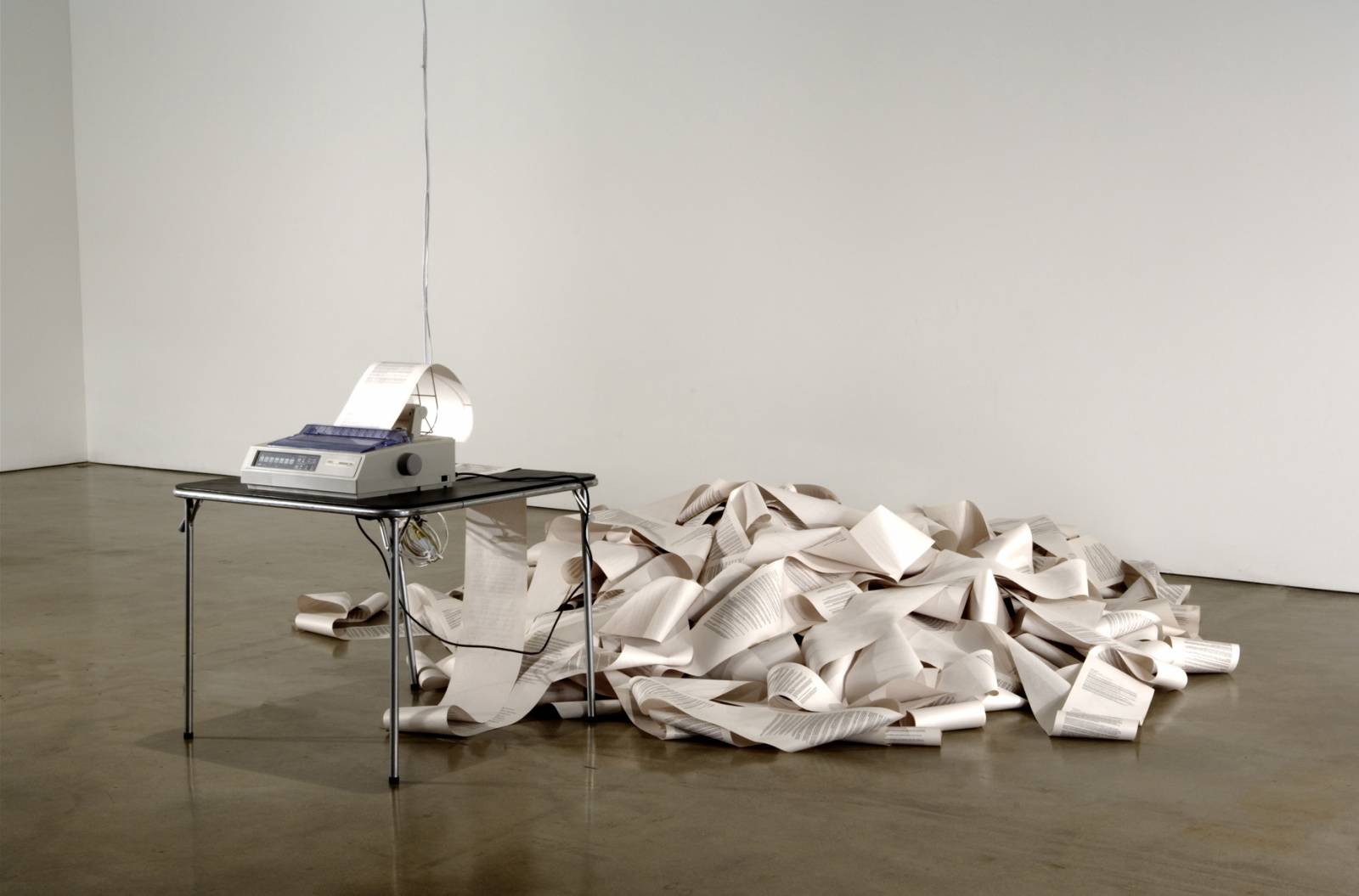

Hans Haacke, News, 1969/2005. Installation view, “State of the Union,” Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2005. © Hans Haacke / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Pauline Oliveros, circa 1967. Courtesy of the CCM Archive, Mills College, Oakland, CA.

The Builders Association, Elements of Oz, 2015. Photo: Gennadi Novash. Courtesy of Peak Performances @ Montclair State University.

Ain Gordon, A Disaster Begins, 2009. Veanne Cox. Here Arts Center, New York. Photo: Jason Gardner. Courtesy of the photographer and Pick Up Performance Co(s).

Hopscotch, 2015. Directed by Yuval Sharon. Produced by The Industry, Los Angeles. Photo: Dana Ross.

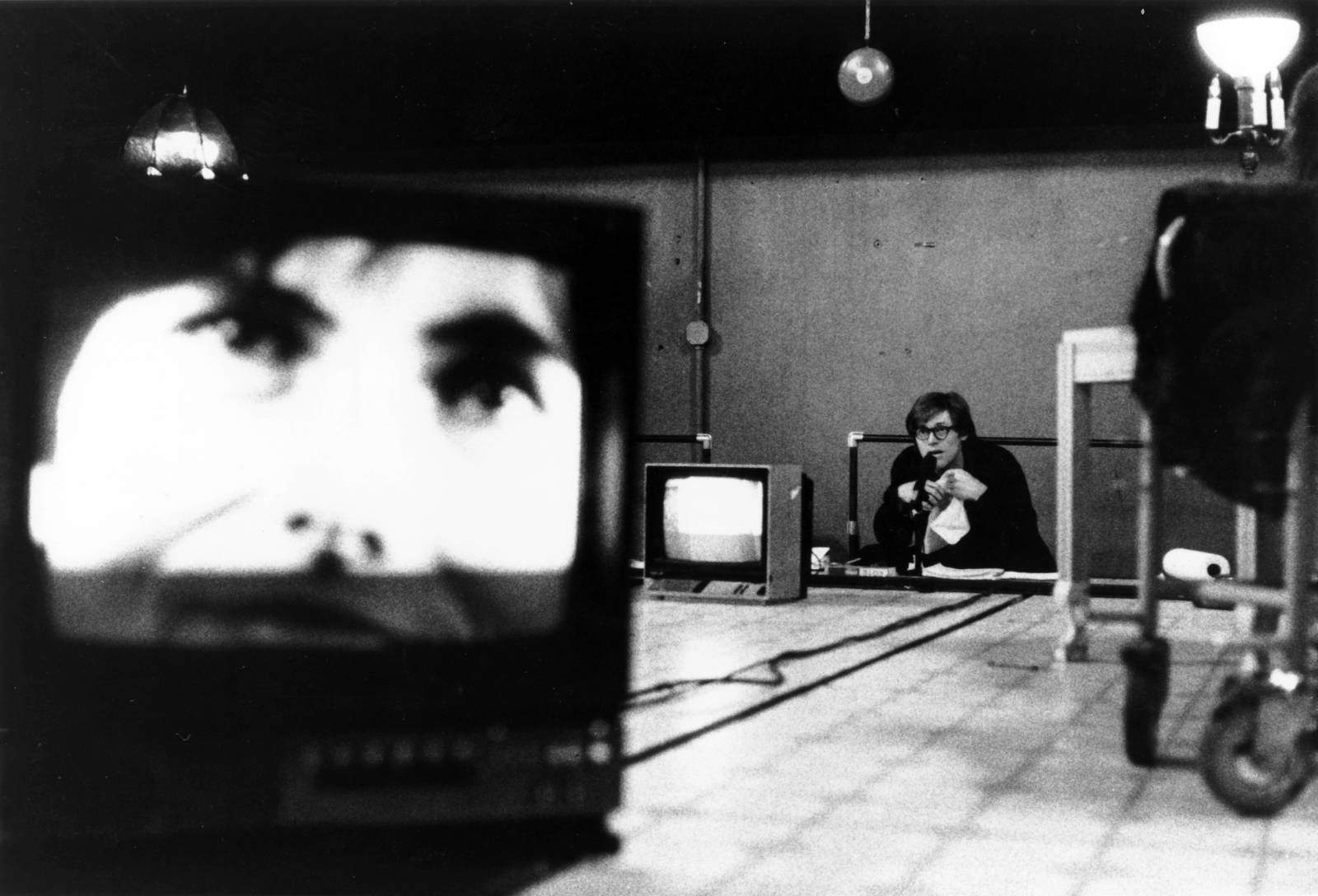

The Wooster Group, BRACE UP!, 1991. Directed by Elizabeth LeCompte. Anna Köhler (on monitor) and Willem Dafoe. Photo © Mary Gearhart.

Tania El Khoury, Jarideh, 2010.

Joanna Haigood and Charles Trapolin, The Monkey and the Devil, performance installation, 2011. Performers: Matthew Wickett, Sean Grimm, Jodi Lomask. Photo: Walter Kitundu.

Jarbas Lopes, Demolition Now, in “SPRING,” curated by Claire Tancons for the 7th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, 2008. Photo: Akiko Ota.

Lisa Bielawa, Crissy Broadcast (part of Airfield Broadcasts), San Francisco, 2013. Photo: James Block.

Erwin Wurm, One Minute Sculpture, 1997/2005. © Erwin Wurm. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

Ethyl Eichelberger as Minnie the Maid, 1981. Photo: Peter Hujar. The Peter Hujar Archive. Courtesy of Pace MacGill and Fraenkel Galleries.

Wu Tsang with Alexandro Segade, Mishima in Mexico, 2012. Color HD video, 14:32 minutes. Courtesy of the artists, Clifton Benevento (New York), Michael Benevento (Los Angeles), and Isabella Bortolozzi (Berlin).

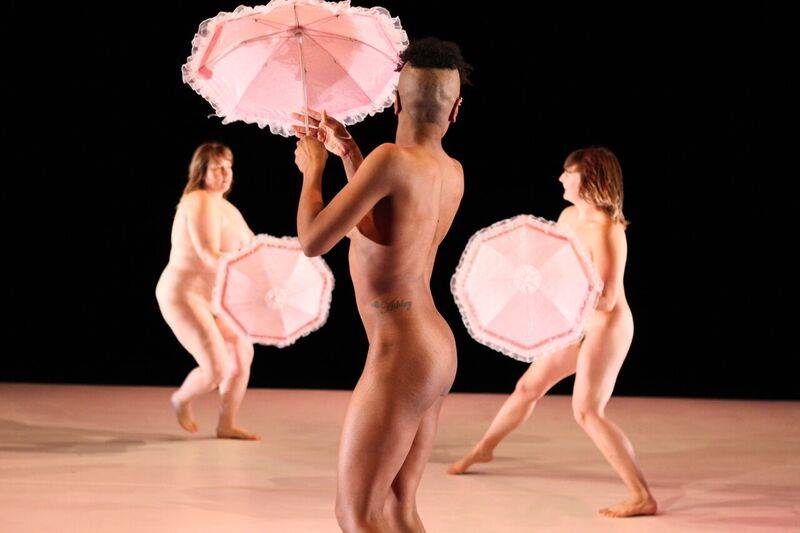

Young Jean Lee, Untitled Feminist Show, 2012. Baryshnikov Arts Center, New York, 2012. Hilary Clark, Regina Rocke, and Katy Pyle. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

Romeo Castellucci, On the Concept of the Face Regarding the Son of God, 2010. Philadelphia Live Arts Festival, 2013. Photo: Kevin Monko.

Jérôme Bel, Le dernier spectacle (The last performance), 1998. Photo: Herman Sorgeloos.

Troubleyn / Jan Fabre, Mount Olympus, 2015. Performance lasts 24 hours. Photo © Wonge Bergmann for Troubleyn / Jan Fabre.

Siobhan Davies Studios, Roof Studio, London. Photo: Peter Cook.

Emily Roysdon, Sense and Sense (a project with MPA), Sergels torg, Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

David Lang’s home studio. Photo © Jorge Colombo.

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1964 (replica of 1913 original). Wheel and painted wood. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of the Galleria Schwarz d’Arte, Milan, 1964. © Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2016.

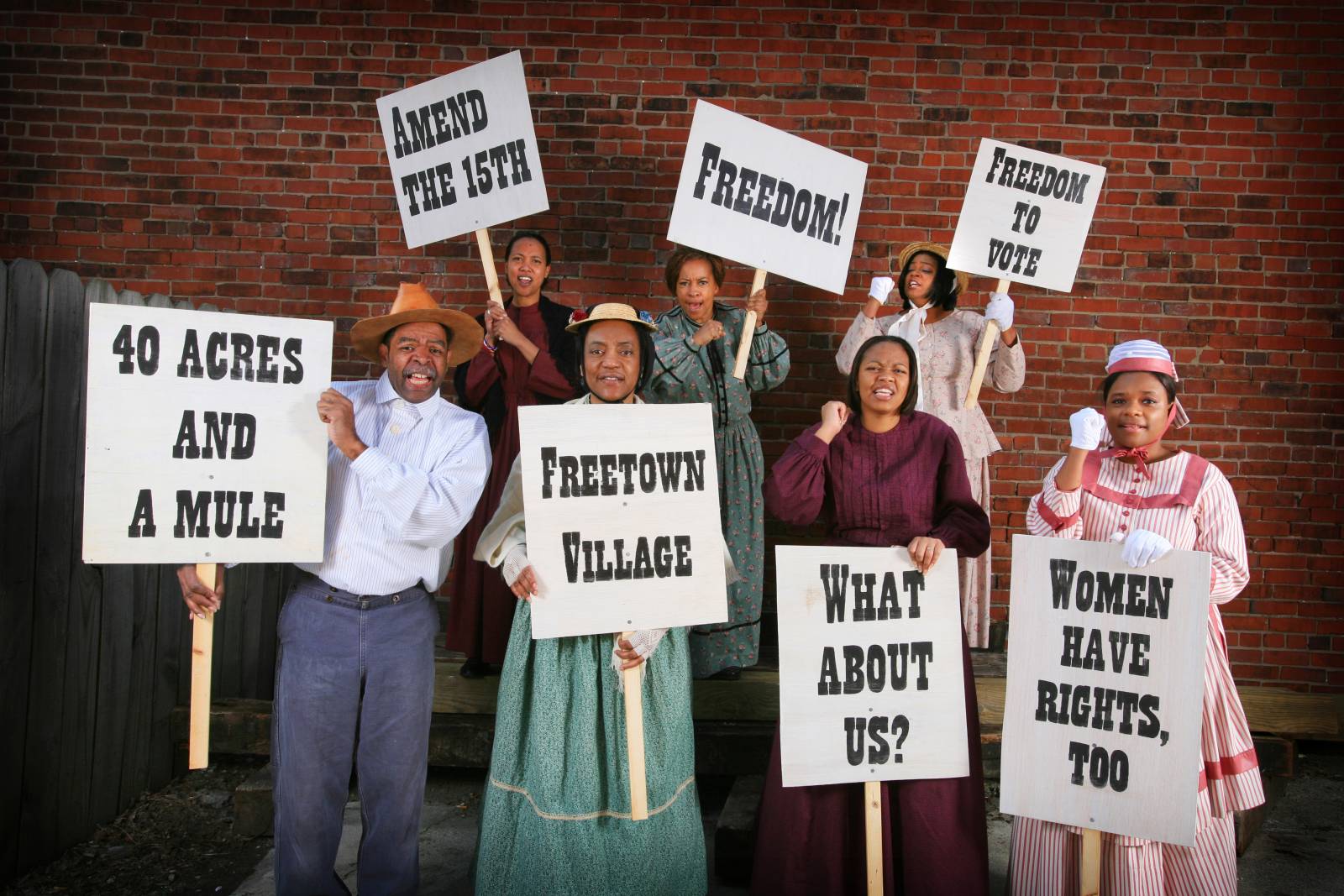

Historical interpreters from Freetown Living History Museum, as part of Allison Smith’s 2008 project The Donkey, The Jackass, and The Mule, with the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Photo: Allison Smith and Michelle Pemberton.

Rimini Protokoll, Situation Rooms, 2013. Photo © Ruhrtriennale / Jörg Baumann.

Jeanine Oleson and Ellen Lesperance, We Like New York and New York Likes Us, 2004. A “wry look back” at Joseph Beuys’s performance with a coyote, I Like America and America Likes Me, René Block Gallery, New York, 1974. Courtesy of the artists.

Christine Hill, Volksboutique Organizational Ventures, 2001. Mixed-media installation, Kunstverein Wolfsburg, Germany. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk, 1989. Performance. Performance documentation: Kelly & Massa Photography. Courtesy of the artist. © Andrea Fraser.

Theaster Gates, Dorchester Projects, Chicago, 2012. © Theaster Gates. Photo © Sara Pooley. Courtesy of White Cube.

John Cage, two pages from 4'33" (original version, in proportional notation), 1952/1953. Ink on paper, 11 x 8 1/2" each sheet. Acquired by The Museum of Modern Art through the generosity of Henry Kravis in honor of Marie-Josée Kravis. © 1993 Henmar Press Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission of C. F. Peters Corporation. Photo © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

Yoko Ono, Painting For The Wind, summer 1961. First published in Yoko Ono: Grapefruit (Tokyo: Wunternaum Press, July 4, 1964). © Yoko Ono.

Rosemary Lee, Square Dances, 2011, commissioned by Dance Umbrella. Square Dances took place in four central London squares throughout a day, with different casts in each: 10 children in Woburn Square, 100 women in Gordon Square, 35 men in Brunswick Gardens, 25 dance students in Queen Square. Each performance involved bells, ranging from a huge church bell that struck every minute; to a handmade musical instrument using bells within its barrel structure, created and composed by Terry Mann; to tiny hand bells for the dancers. Photo: Hugo Glendinning.

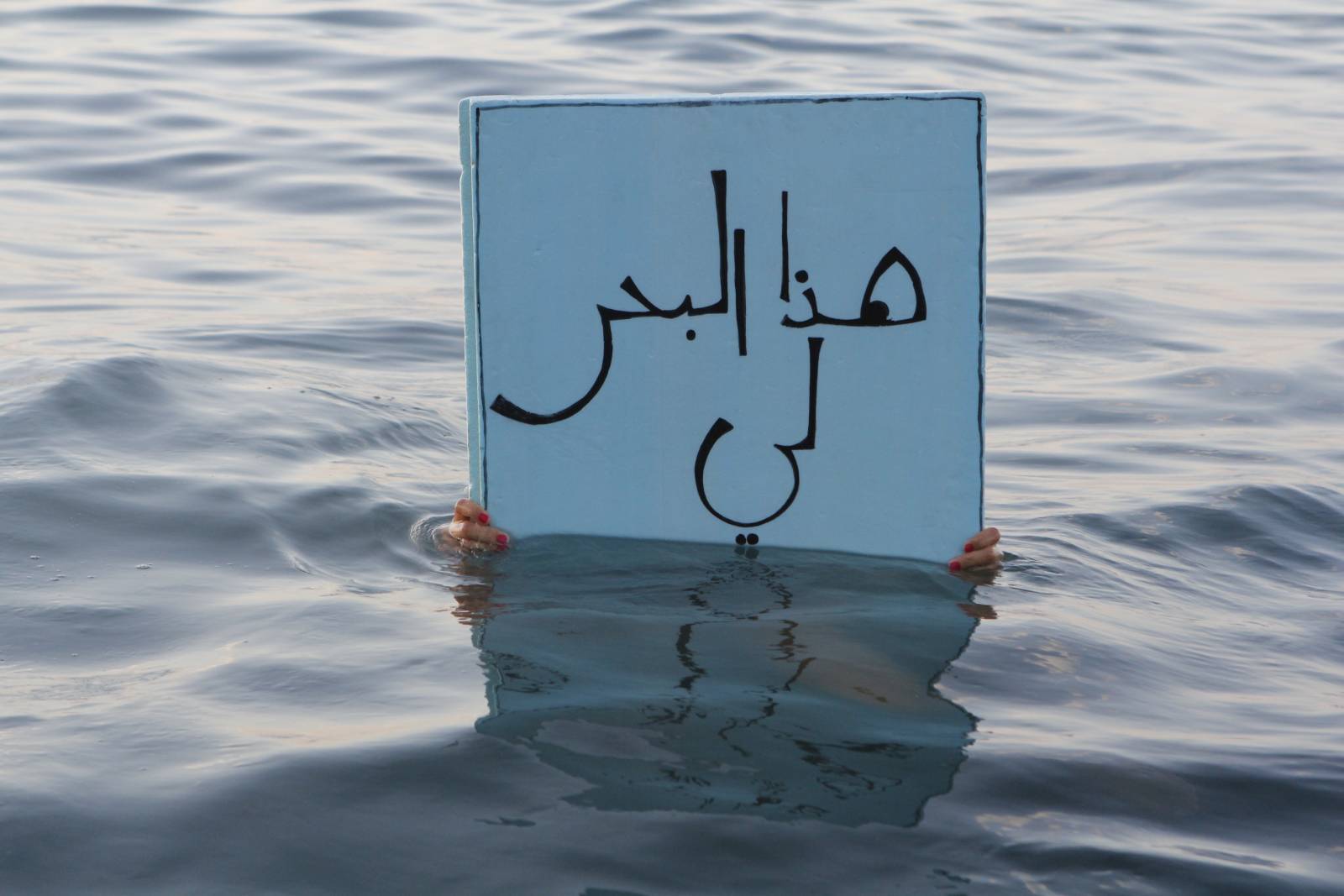

Dictaphone Group, This Sea is Mine, 2012.

Joanna Haigood and Wayne Campbell, Ghost Architecture, 2004. An aerial dance installation centering on the architectural and social history of the site. Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco.

Ann Hamilton, the event of a thread, 2012–13. Park Avenue Armory, New York. Curated by Kristy Edmunds. Photo © Ian Douglas.

Robert Wilson and Marina Abramović, The Life and Death of Marina Abramović, premiered 2011. Park Avenue Armory, New York, 2013. Foreground: Willem Dafoe. Photo: Joan Marcus. Courtesy of Park Avenue Armory.

Richard Maxwell, Neutral Hero, 2012. The Kitchen, New York. From left: Janet Coleman, Bob Feldman, Lakpa Bhutia, Andie Springer, Jean Ann Garrish. Photo © Paula Court.

Ann Liv Young, The Bagwell in Me, 2008. Photo: Scott Newman, Revel in New York.

Xavier Le Roy, “Retrospective,” 2012–. Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, 2012. Photo: Lluís Bover. © Fundació Antoni Tàpies.

Ethyl Eichelberger as Minnie the Maid, 1981. Photo: Peter Hujar. The Peter Hujar Archive. Courtesy of Pace MacGill and Fraenkel Galleries.

David Levine, Habit, 2012. Installation view, Luminato Festival, Toronto, 2011. Photo: David Levine.

Rimini Protokoll, 100% Yogyakarta, 2015. Teater Garasi, Yogyakarta, Java, Indonesia. © Goethe-Institut Indonesien / KDIP Viscom.

Bebe Miller Company, A History, 2012. Angie Hauser and Darrell Jones. Photo: Michael Mazzola.