Since the early ’90s, I have found myself embroiled in discussions about the possibilities and perils of this keyword—“performativity.” Why was I there? And why am I still returning to the topic now? I suppose it is because at that earlier point in time I made the suggestion that gender might be understood as performative, and that led to a rather long discussion with many people in different parts of the world on questions such as, “What is the difference between performance and performativity?” and “Is performativity a way of talking about social construction?” and “Are all bodies or, rather, is everything about the body constructed, and does that mean that bodies lack materiality?” If gender is performative, and performativity is one way of specifying social construction, does that mean that “we choose our genders” or that “we are determined by social and cultural norms”?

It is not that such questions came to me in dreams or woke me from my sleep, but they did continue to arrive at my door, knocking. That knock often took the form of invitations to speak, which, once accepted, compelled the body to get on a plane, watch out for issues of adequate hydration, sleep in strange hotels, and arrive in person, as a body, in order to vocalize a response of one kind or another. What was the relation between those repeated lectures on performativity and the concept—or practice—that I was trying to elaborate?

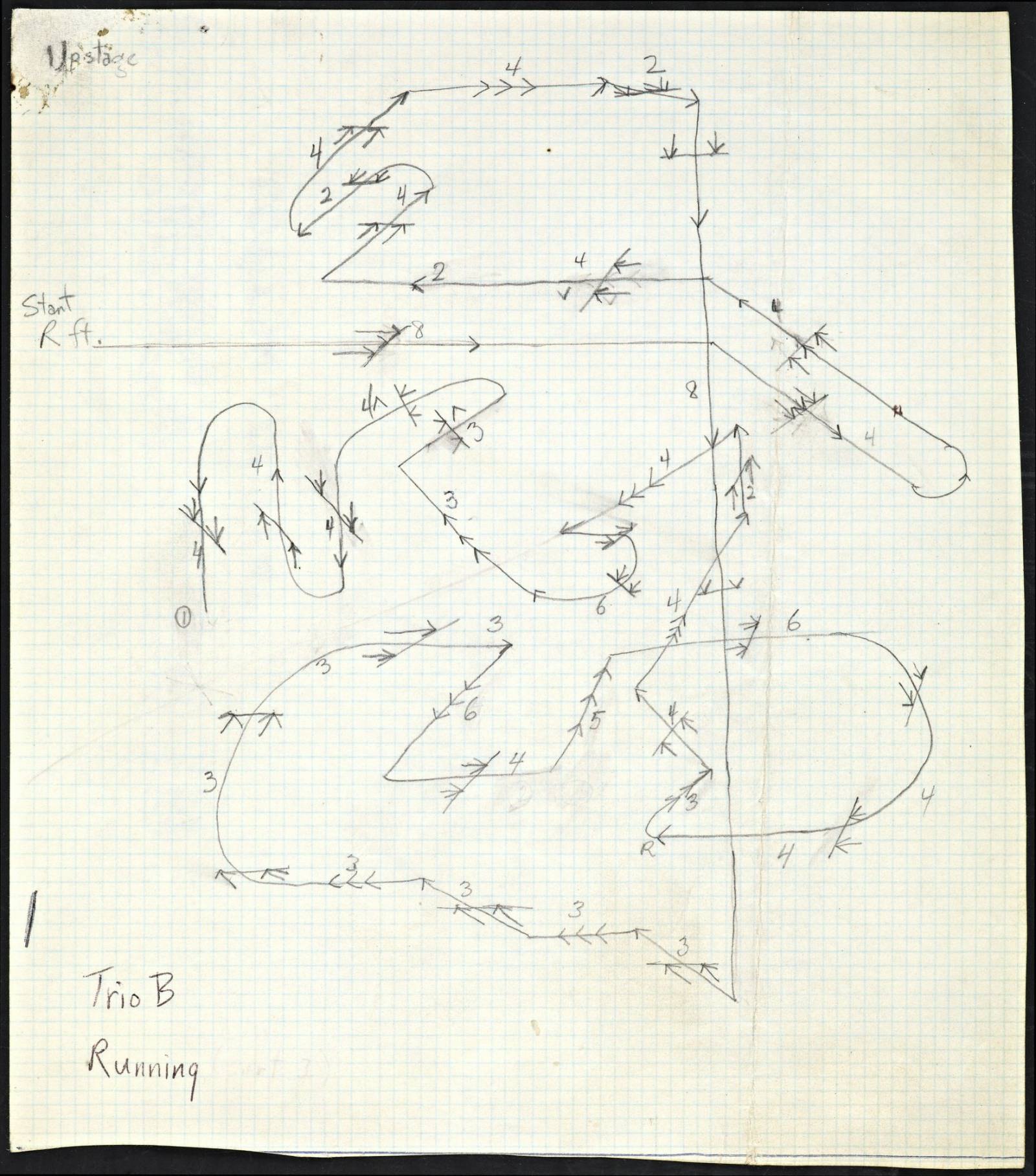

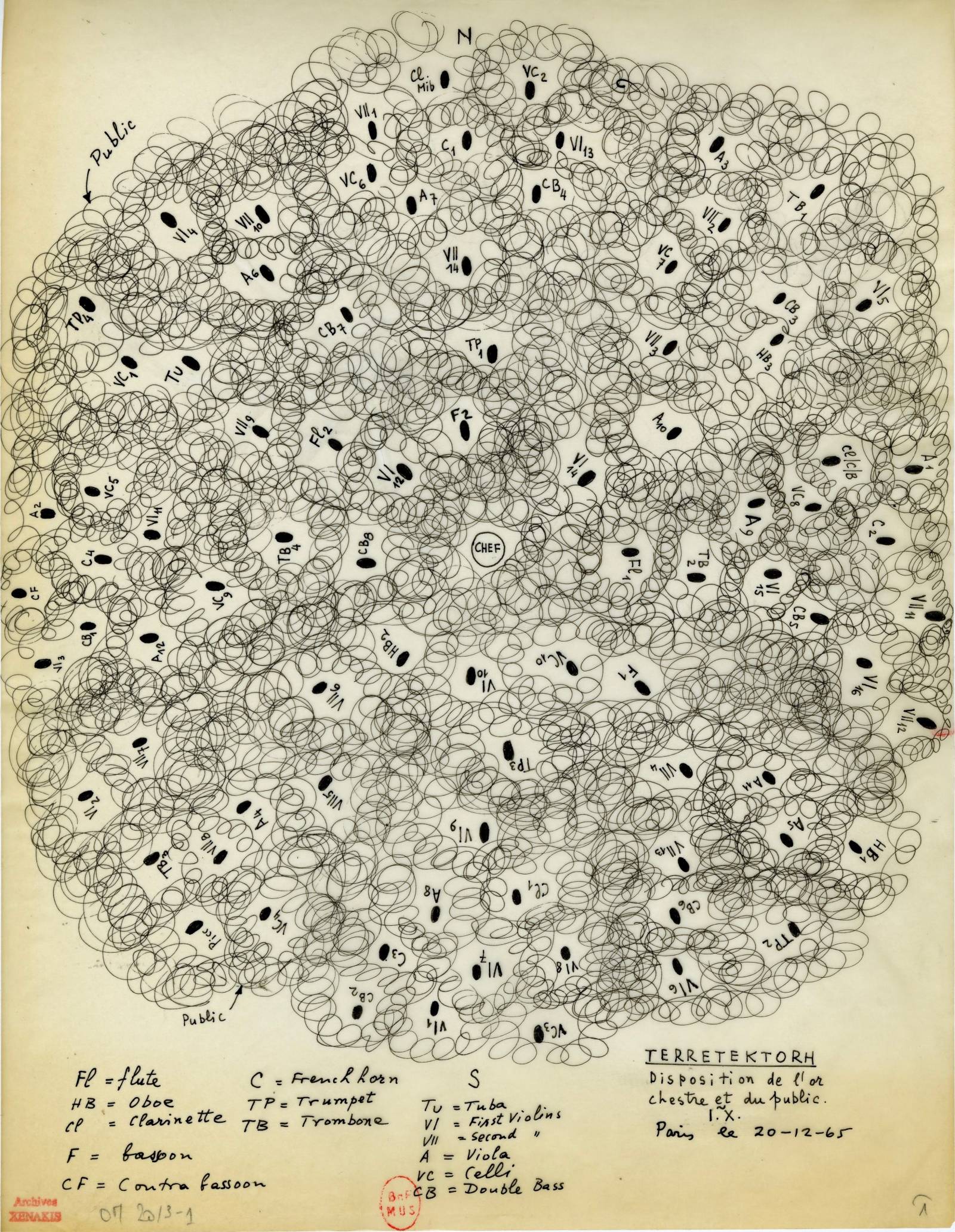

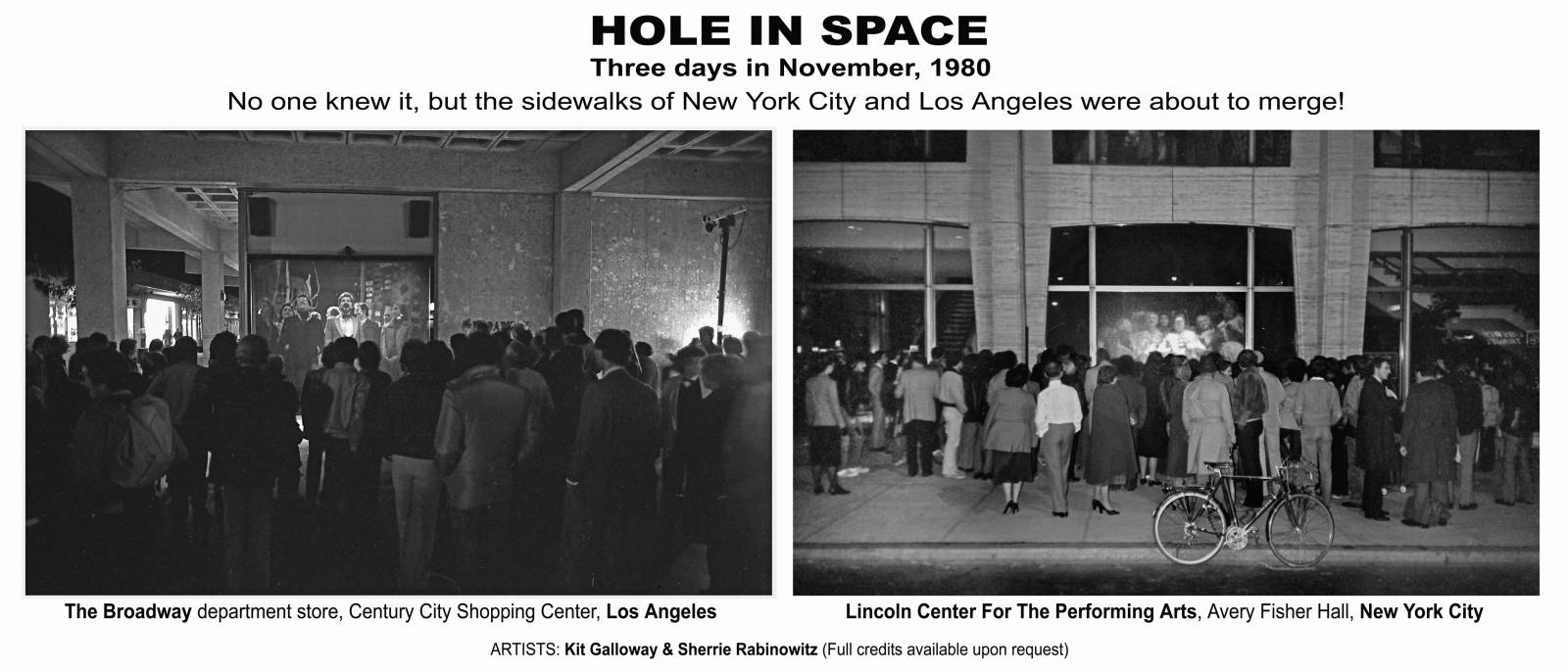

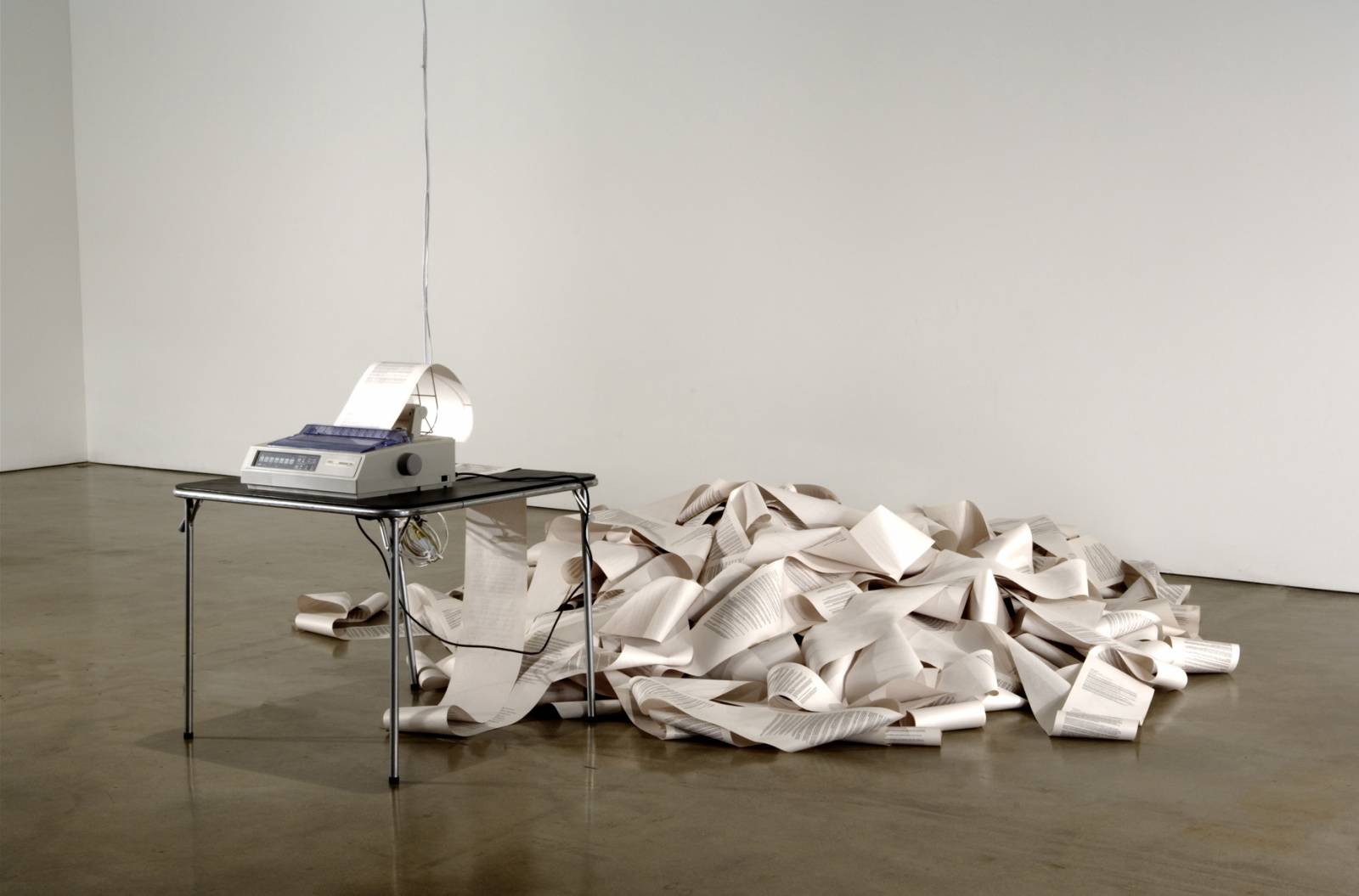

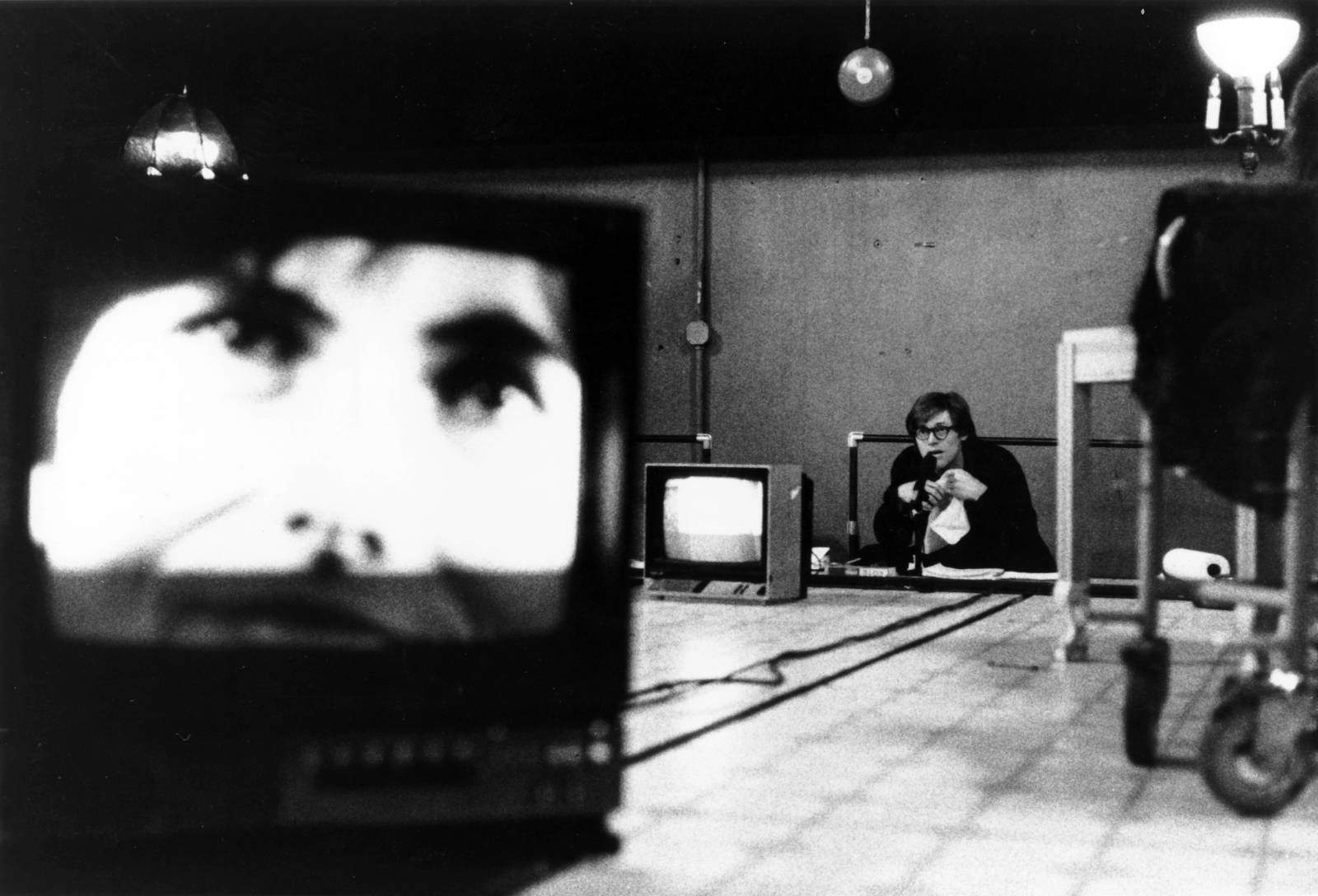

It seemed at first that I was speaking within literary theory, then with an emerging queer theory, but of course I was also in conversation with many other scholars and artists working on essays, books, and compelling art projects thinking about performance in time and space. One position within that increasingly productive field argues that performance emerges from shared social worlds, that no matter how individual and fleeting any given performance might be, it still relies upon, and reproduces, a set of social relations, practices, and institutions that turn out to be part of the very performance itself. In a way, “social work,” the name of Shannon Jackson’s book, names as well at least two dimensions of performance condition and exceeds its status as a punctual act. Different ways of working together constitute the social condition, even the very stuff, of performance itself; in turn, performance brings with it the chance to re-create community through various preparatory collaborations among objects, others, and technologies. Even the solo, the monologue, or the highly individuated verbal performance (which is what most academic lectures tend to be) requires a support team, a space, a time, a schedule, a set of working and enabling technologies, a slew of objects, networks, and temporally organized processes that do not explicitly appear in the distinct set of moments when the body of the performer becomes seen, heard, or communicated. We rightly think of all the hidden labor, largely unpaid or underpaid, that makes the punctual act of utterance or action possible. But the “action” is better described as a choreography of objects, networks, and processes that cross the human and the nonhuman.

From such a perspective, we are compelled to think anew about some rather fundamental theoretical questions. First, are the human and object worlds that together make a performance possible also what make up the performance, such that there is a nonhuman dimension to all performance? That is, is performance always engaging the nonhuman conditions and components of our own action? Are such worlds carried and conveyed, made or unmade, in the performances that we do and are, the ones we see and hear or register in some other way, those that lay claim to our responsiveness and, by acting on us, tacitly restructure how we sense the world at all? Even at this moment when I write (or speak), I rely on the work of various scholars and artists to help me think about how this happens, and this dependency, if you will, structures this performance; their work is in my work, and their thought is in my thought, sometimes in ways that preclude the possibility of an explicit citation.

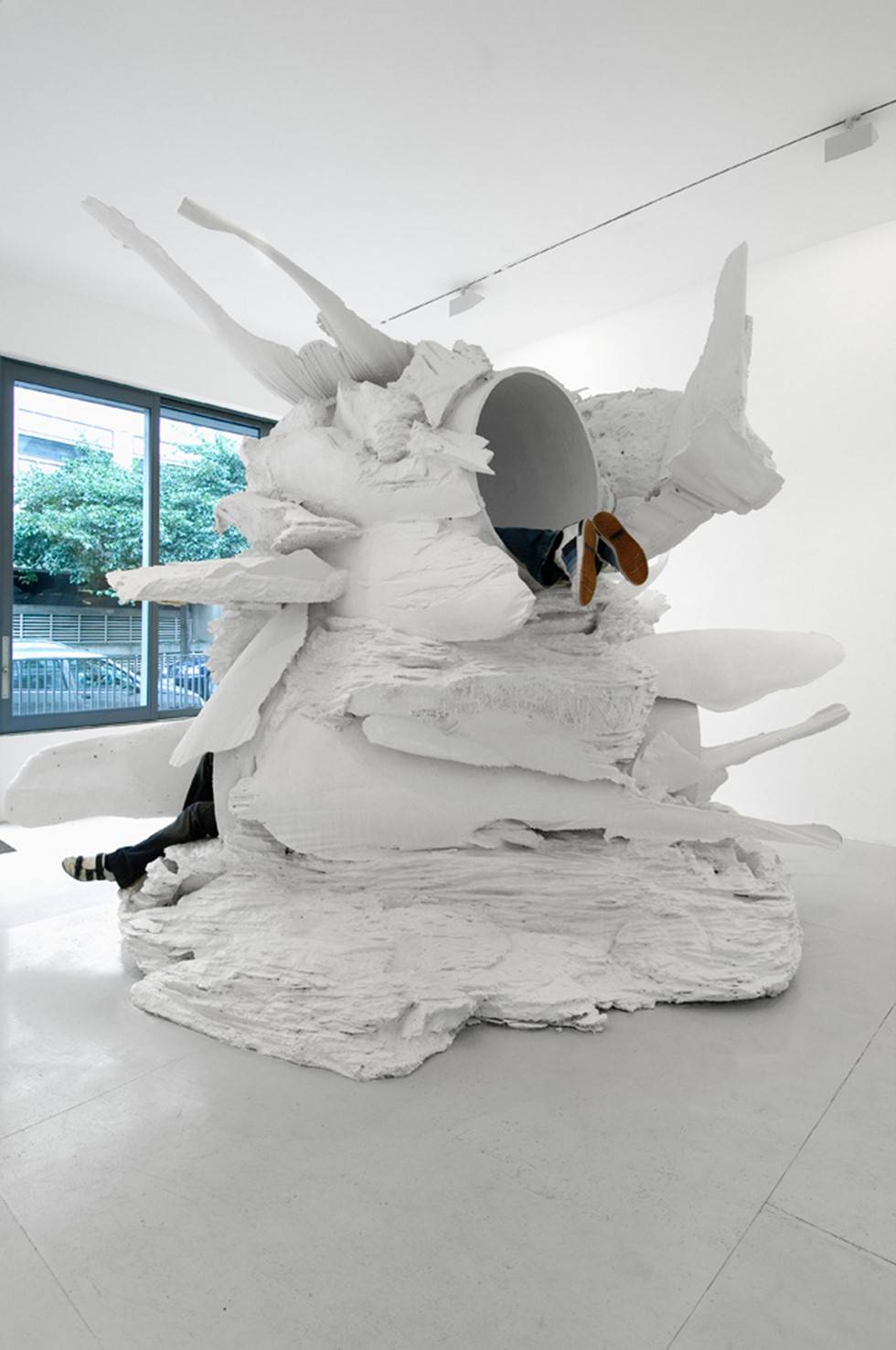

The body who appears in a lecture space relies on the support that the space provides, and so relies on the support that the space receives. These modes of interdependency are both presupposed and deflected as the individual speaker speaks. We become aware of it, of course, when microphones suddenly break down or lights dim when they are not supposed to. Even though we groan at such moments, they show us how very lucky we are, we humans who transpose and amplify ourselves by nonhuman means. We are trying to move and speak and perform in a world that is supported (the sense of the world depends on supports, and the world, in turn, becomes our support). There are bodies behind and to the side of this body, and they are working together, even when that plurality sometimes collapses into the figure of the one, even when no one else shows up on stage when I do.

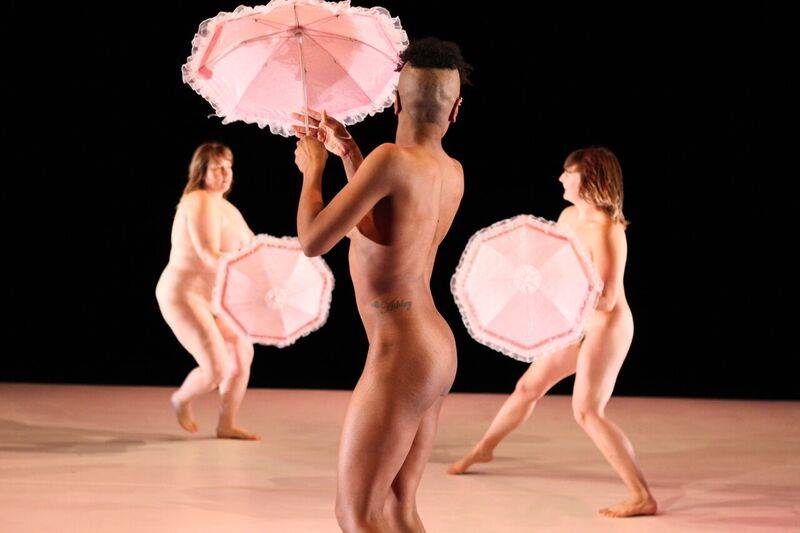

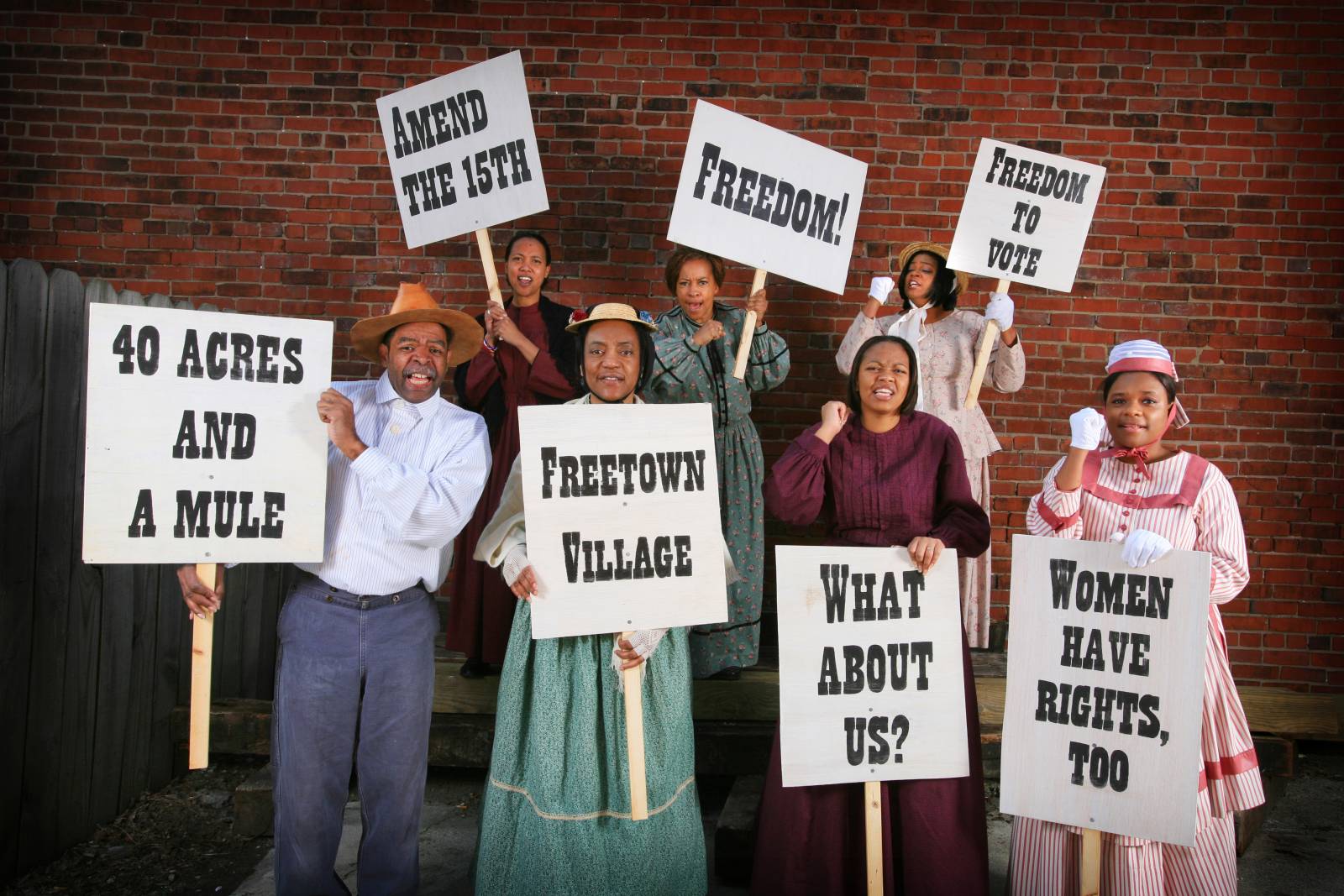

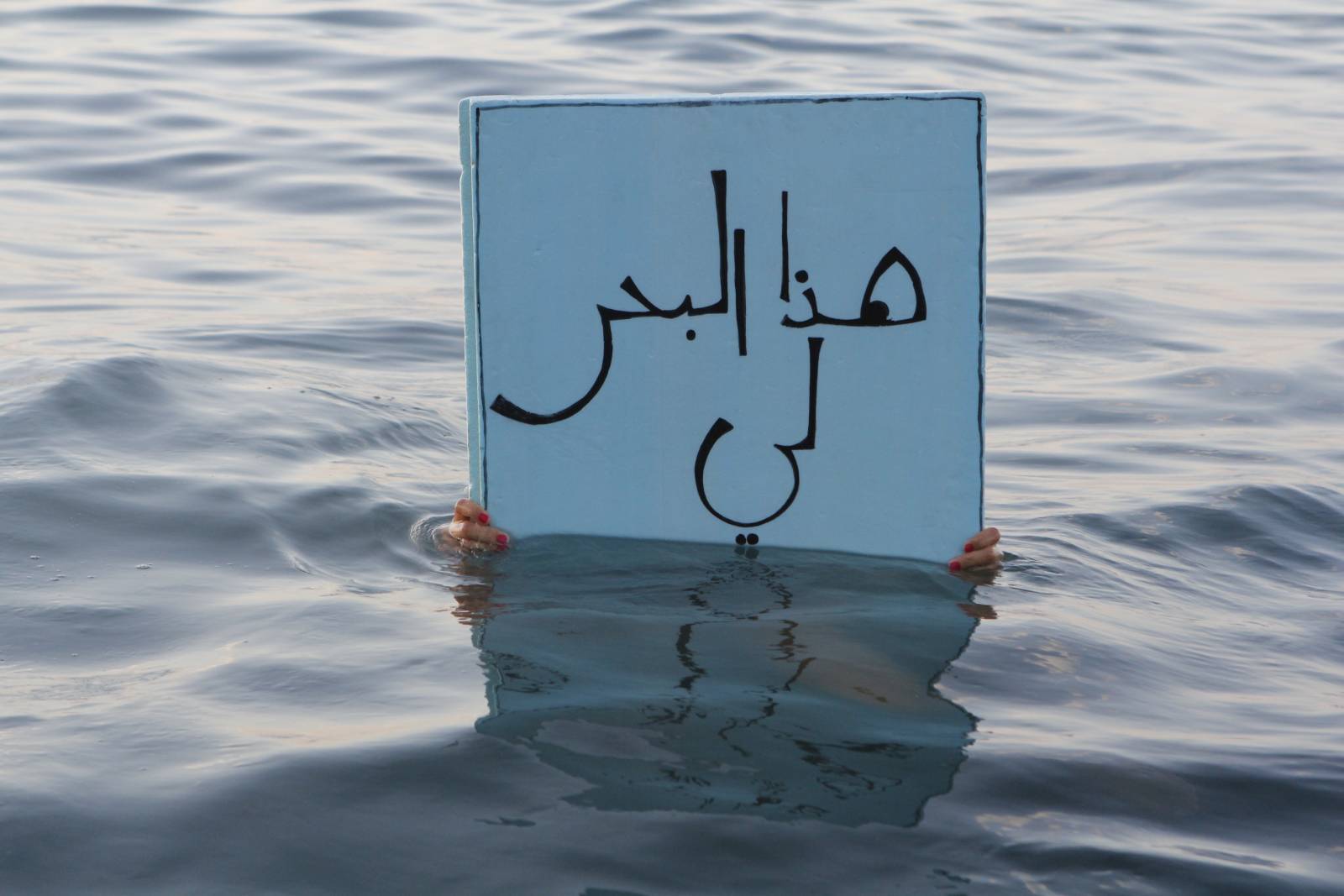

I wanted to say something like that when I spoke about gender as performative or, at least, I came to see things that way in the course of responding to all those questions and keeping new company. No one really performs a gender alone, no matter how beautifully idiosyncratic the performance might be. That does not mean that everyone is performing it in the same way—not at all. But even under conditions of extreme and punitive isolation, the kind that follows from performing gender in ways that are considered non-normative in highly hostile spaces, one suffers alone, but there is always the shadow of company, of others who would be treated the same way were they present. One finds oneself inside a category not of one’s own making. Of course, it is this particular body who suffers and enjoys, and no other, but that suffering and enjoyment is already a relational matter—gender is performed for a someone, even if that someone does not yet exist; and sexuality is lived in relation to a world of others, whether it is reclusive, auto-erotic, externalized, or exposed. When someone suffers as a consequence of having broken with a cultural norm, or for having shown how the norm can or must be broken or bent, that person has entered into a cultural and political struggle whether or not one meant to, whether or not there are proximate signs of others in solidarity. An isolated act can, in fact, be a radical petition for solidarity, as if to say, “Where are those of you who will support me now?” Gender is not gender if it does not imply the social dimension of a bodily being, the way that the body refers to a broader world and exceeds the one who bears or does it, even as that one remains in some sense singular.

But the same goes for performance—and perhaps this is part of the link between them. Performance is always an action or event that involves a number of people, objects, networks, and institutions, even when performance takes place without a stage and in the briefest of moments, gathered up and dispersed in evanescence. For it is for and with someone or some set of nonhuman things and movements, always relying on a ground or background, or social world—a fleeting act for a passing crowd—that performance comes forth as “performance” at all. Even when infrastructure fails, something or someone takes up some space, pointing to that loss. So performance is not the self-constituting act of a subject who is grounded nowhere, acting alone. If performance brings a subject into being, it does so only in terms of the social and material coordinates and relations that make it possible or that form its scene of intervention. The boundaries of the body that establish singularity are precisely the means by which sociality comes into being. For every question of support and tactility depends on a body that is, from the start, given over to the material and social conditions of its own persistence, bound up with that human and nonhuman support without which . . . nothing.