Claudia La Rocco

Claudia La Rocco, a poet, critic, and performer, is editor-in-chief of Open Space, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s digital publication and community platform.

This is the word they chose for me. (And I picked ephemerality, for reasons that seemed clearer to me at the time, which, more on that later.)

I did a Google search. It didn’t help much. And then my mom sent me this:

Duration late Latin durare “to harden”. Used by Chaucer and then after 1600. Not in Shakes. Chaucer AND YAF HEM EKE DURACIOUN. . . . A use for DURATION that was very common in the 40s and 50s was that it meant “the length of the war”. People were drafted into the service not for 2 years but for “the duration”. This meant huge upheaval because the duration was unknown. Most people felt it had to be and accepted it. Buildings were seized and turned into shelters, hospitals, troops housing, etc. “for the duration.” After the war, the time I know, people used the term in a sort of joke. “How long til the chicken is cooked?” “Dunno but I will stay for the duration and watch it” etc.

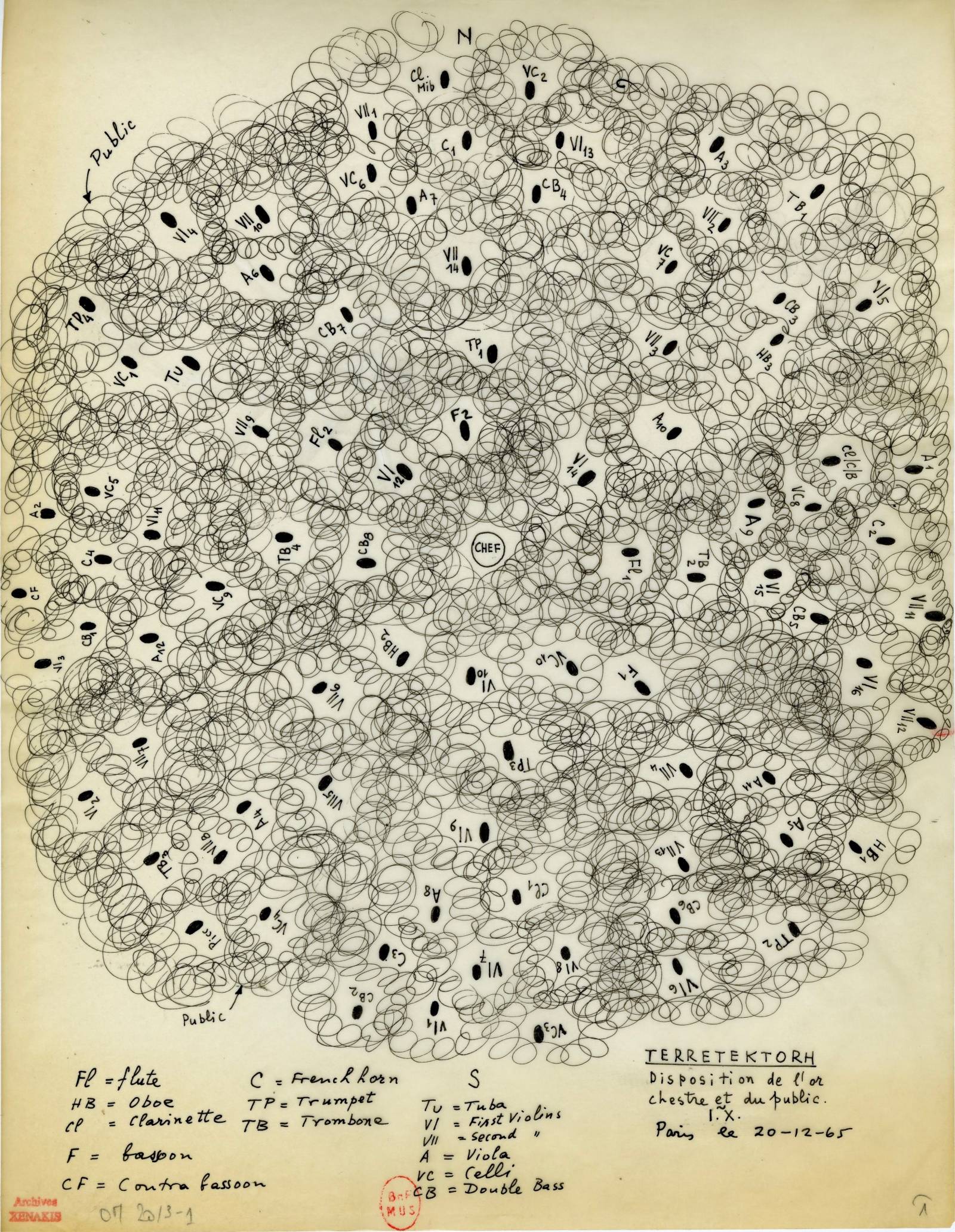

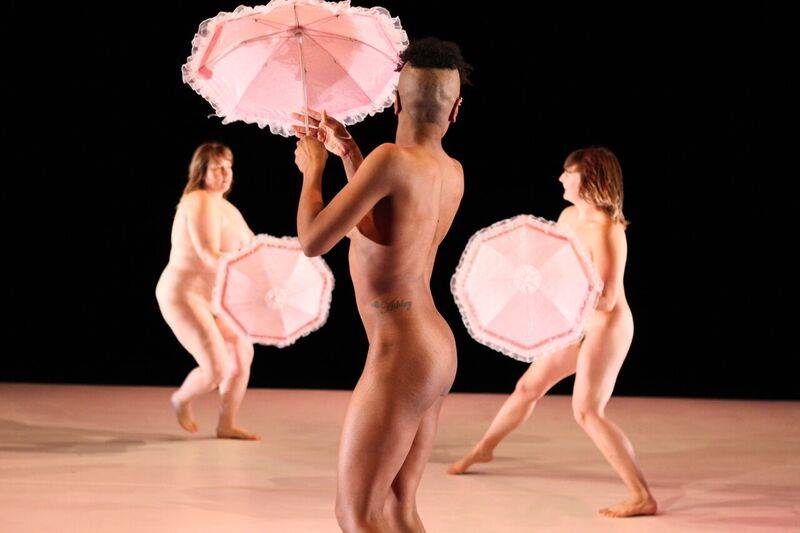

So. Yeah, staying for the duration and watching it: that pretty much sums up the dance and theater approach to anything that happens ever. How long till the chicken’s cooked?? I keep thinking of Sarah Michelson’s Devotion Study #1—The American Dancer (2012) at the Whitney Biennial a few years back, what madness it was for the museum, as if the idea of show times and lines was totally stymieing, and how panties-in-a-knot so many of the dance people got about things being different than they would be at a theater. And then when the visual art people realized that that was just it, that was all it was gonna be, these insane women circling backward and backward and backward . . . well, that was it. Leaving. In droves! Like an uptown crowd at a Cunningham show once the Cage music kicks in (talk about culture clashes). Their chickens were cooked.

It should go without saying that performing arts people make a fetish out of staying till told to go, and visual art folks do the same, only in the opposite direction: just try getting them to sit still.

I have a sense that durational is equated with rigor. As in, “this is a durational piece.” As in, that good old New England sense of sticking it out, seeing it through. Religious crazies make their way to art temples.

I think I tend to use it that way, when writing or speaking about an artist. (Maybe not so much in thinking, which is telling, no? I am obviously translating to another crowd, maybe trying also to prove something. And that makes me think of something Sarah M. said to me once in an interview about museums being hot to trot for dance. She was talking about that very Whitney show, in fact, and being rather tickled with the walkouts: “I do feel extremely grateful to watch the work translate outside its home into another environment,” she said, “or watch my intention translate.”)

And of course there is the good old-fashioned sexual meaning of duration. Nobody wants a two-minute man.

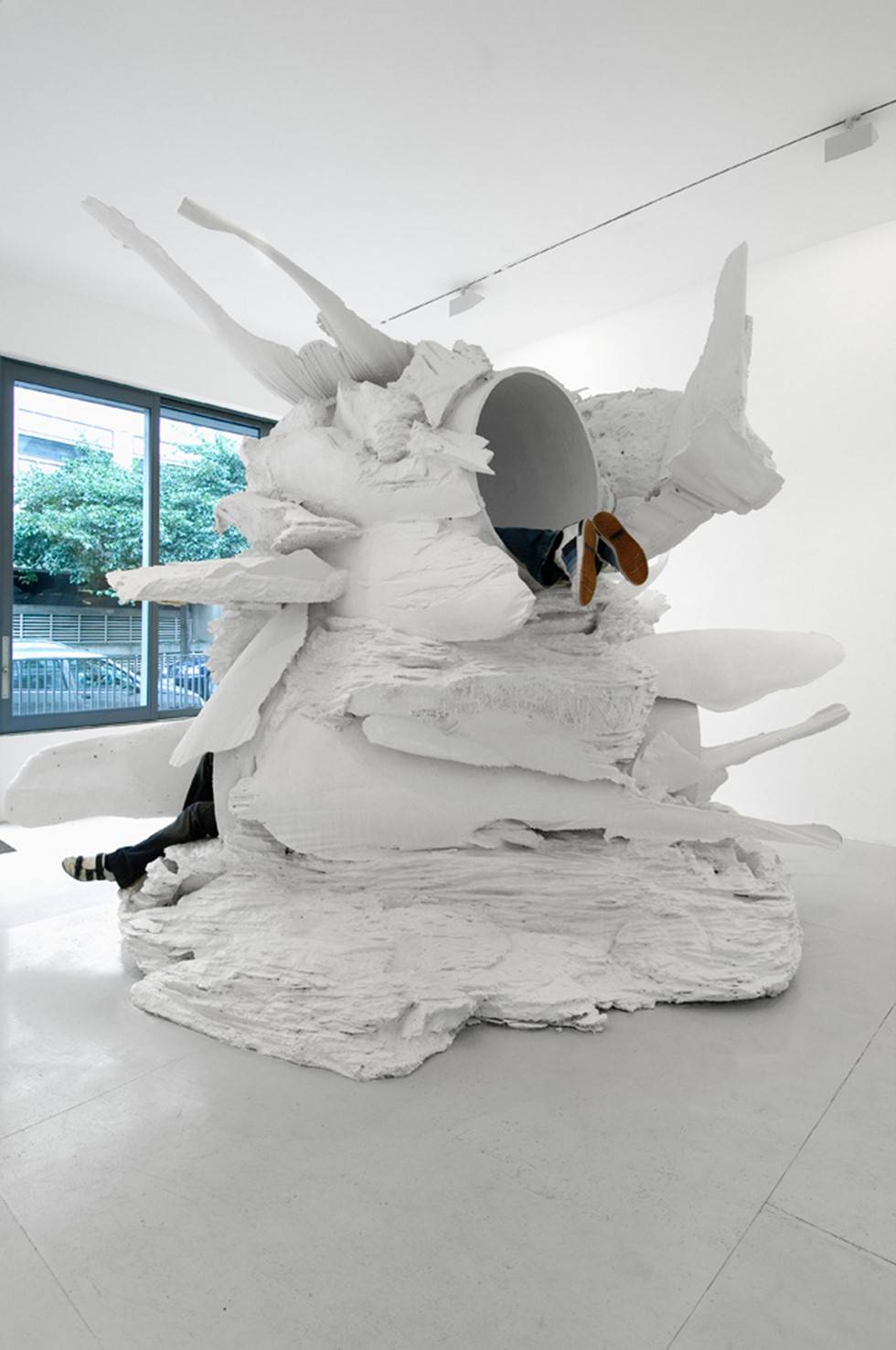

In the performing arts, do we all need it to last because once we walk out into the night air, that’s all she wrote? There’s no luxury of returning to the gallery, circling (backward or fore) that luscious sculpture on its pedestal, sitting there so patiently. Of course objects have shelf lives. Of course objects aren’t so “in” right now anyway. But still. It matters whence your traditions spring.

Am I answering any of your questions, Shannon and Paula? I certainly think of my writing as time-based—long to think about, quick to dispatch. But that’s a digression. Or maybe it’s part of the point.

I keep thinking of that phrase my mother wrote, “The duration was unknown.” Is this maybe one of the things that liveness gives to the institution? Upheaval is the thing we’re all in search of these days, it seems—not wanting things to be only themselves, the same old way they’ve always been. Not war but the theater of war.

I don’t even know what that means, that last line. Or only vaguely. That in a way is the big problem with all these terms that we whip out when threatened. When on thin ice. When the thing is unknown and the simply being with it seems unbearable, untenable. If buildings can’t be seized, we’ll take bodies. If bodies refuse collection, we’ll take the liner notes, please. Something, my dear, to remember you by.

For Further Reference

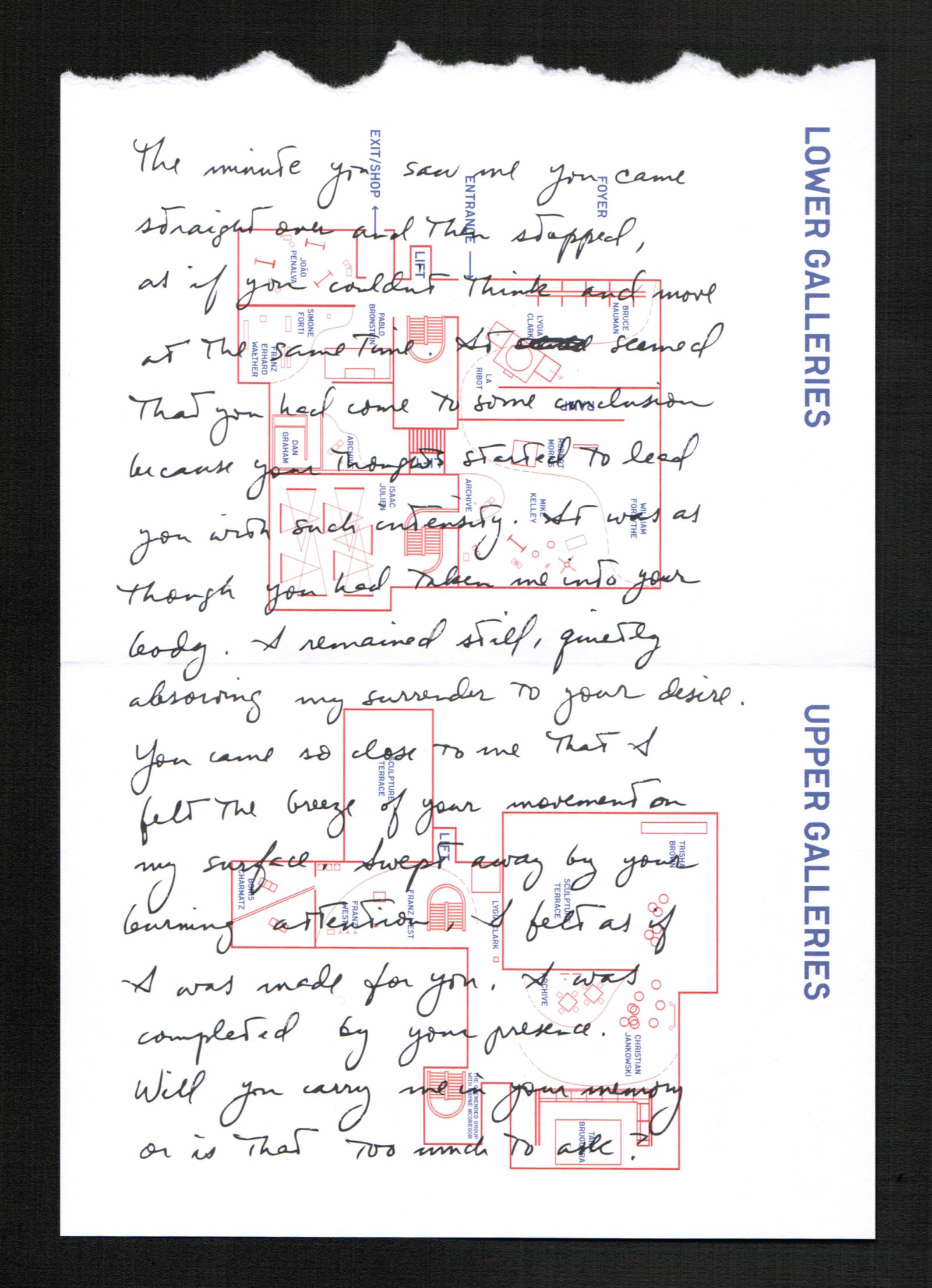

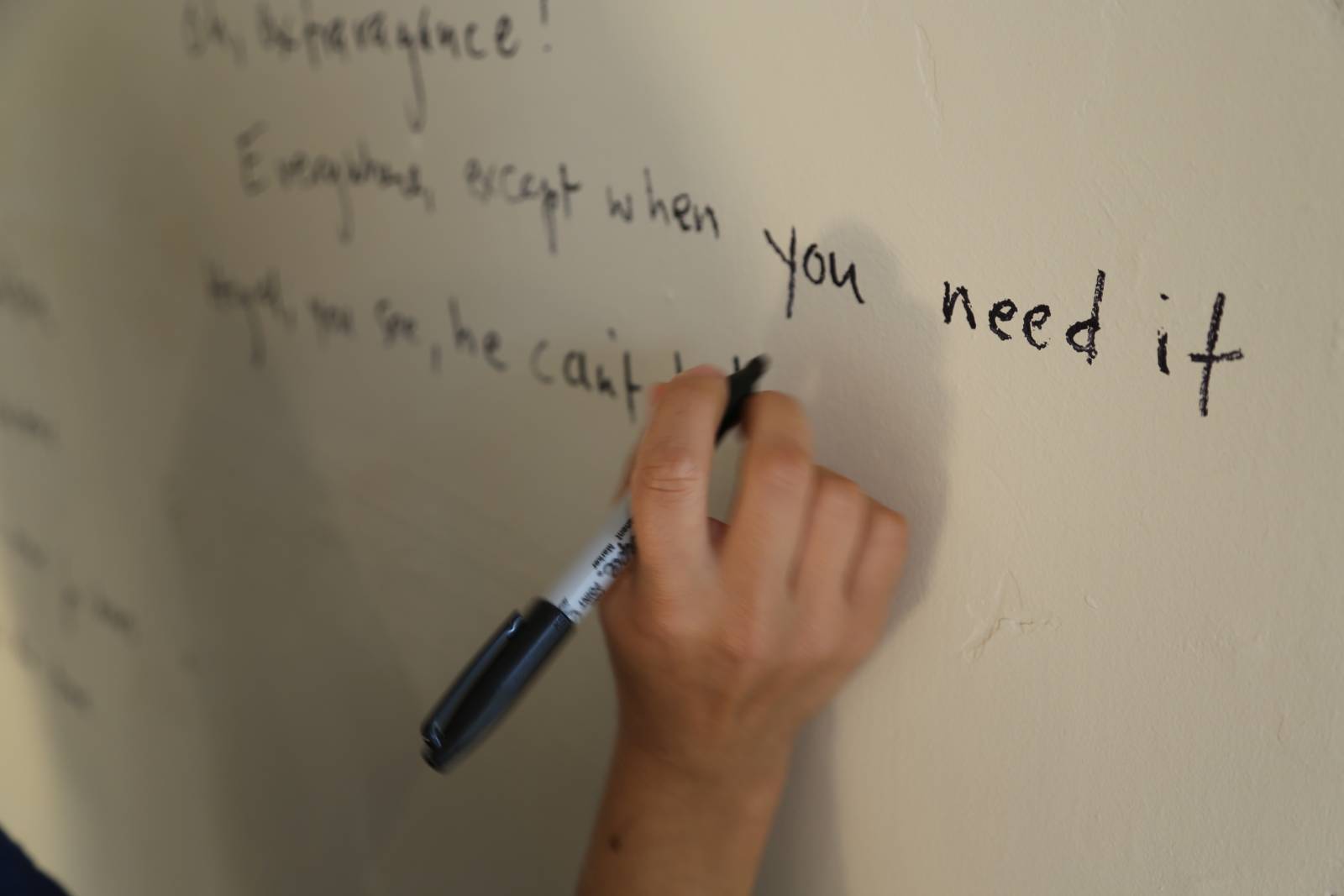

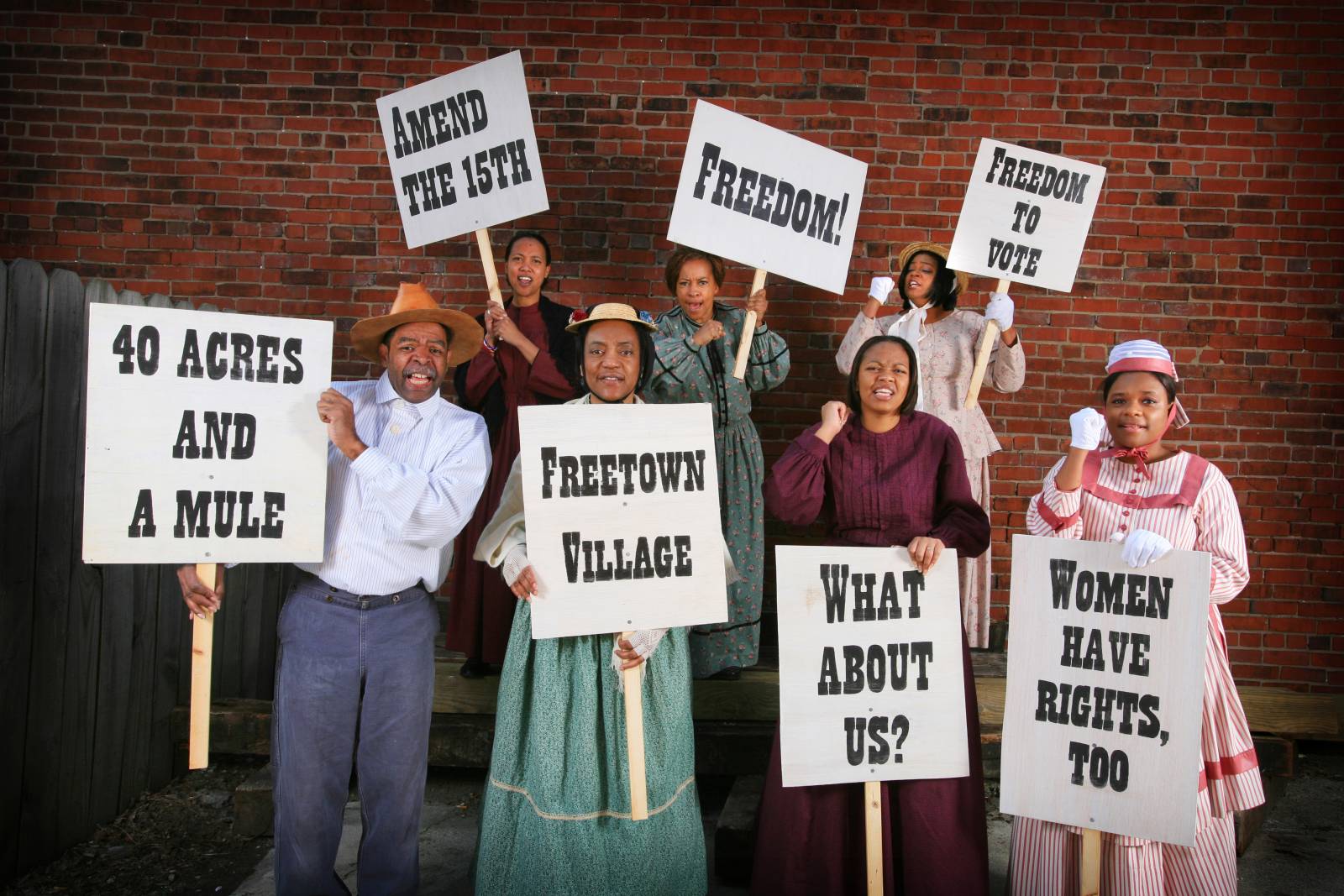

I was at first stymied by the prompt to list works associated with the terms duration and ephemerality . . . don’t virtually all performance works (all things?) possess duration and ephemerality? But then I started thinking of that old warhorse line, “You had to be there,” how it also relates to duration and ephemerality. You have to stick around while it’s happening because the work doesn’t stick around after it’s over—even (especially?) works that come back. And so here’s a list of works that for me exemplify this sort-of double entendre. (Including a poem I wrote: they asked us to include one of our works, and at first I couldn’t think what, since most of what I make exists on the page . . . but this one was a site-specific response, written on the wall of my friend José Carlos Teixeira’s studio as part of his Translation(s), a project developed at Headlands Center for the Arts and then painted over once our residencies were done). It takes the time it takes.

A Family of Perhaps Three, by Gertrude Stein. Target Margin Theater, 2009.

Elevator Repair Service, Gatz, 2006.

Devotion, Sarah Michelson, 2011.

How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere?, Ralph Lemon, 2010.

In Creases, Justin Peck, 2012.

Not Entirely Herself, Vicky Shick, 2011.

July, Jodi Melnick and David Neumann, 2011.

Stopped Bridge of Dreams, John Jesurun, 2012.

Antigone Sr., Trajal Harrell, 2012.

The Collapsable Hole, Radiohole and The Collapsable Giraffe, 2000–13.

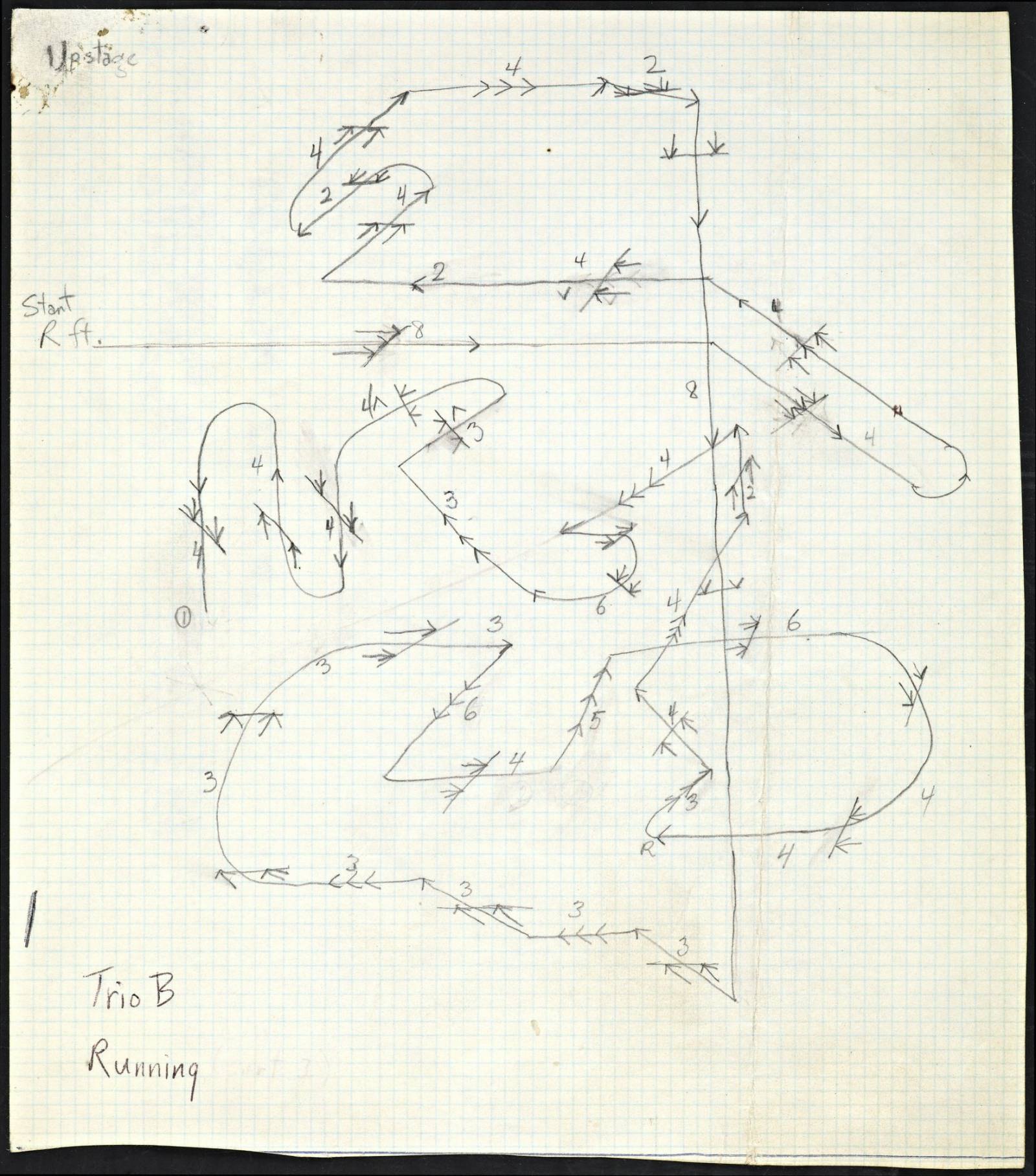

The Merce Cunningham Dance Company, The Merce Cunningham Dance Company, 1953–2011.

“173-177 [or, Facebook Is Inescapable],” Claudia La Rocco, 2013.