Lisa Bielawa

Lisa Bielawa is a singer and composer whose work centers on community partnerships, artistic collaborations, and literary sources.

The root of ephemera—a plural of ephemeron—is a Greek term denoting something (usually a plant or insect) that lasts only one day. The Oxford Dictionary of English traces an expansion of its use from the specific to the metaphoric, denoting something (a thing, person, style, or idea) that has value for only a short time. I was surprised to learn this! The connotation is slightly derogatory, as if value is otherwise expected to last more than just one day. (The example Oxford gives is “Mickey Mouse ephemera”; I found that particularly rich as it triggered in me a kind of nostalgic desire to own some, thereby helping assure its lasting value.)

My understanding of the use of the term in current artistic practice—and my use of the term in talking about my own practice—entails a different and even contrasting notion of value: rather than something having value for “only” a day, the notion of ephemerality suggests to me that something has value precisely because it lasts for only a day. Such art is precious because when it is over, it is gone. The anticipated goneness defines its value, and hence such art must be experienced to its fullest when it is actually happening.

Moreover, when something ephemeral is happening and we are aware that we are open to experiencing it fully, that openness creates in us a uniquely valuable experience. I would even suggest that one of the things that gives an artistic experience value is the degree to which it provides this kind of awareness of the ephemerality of all experience—not just the experience at hand.

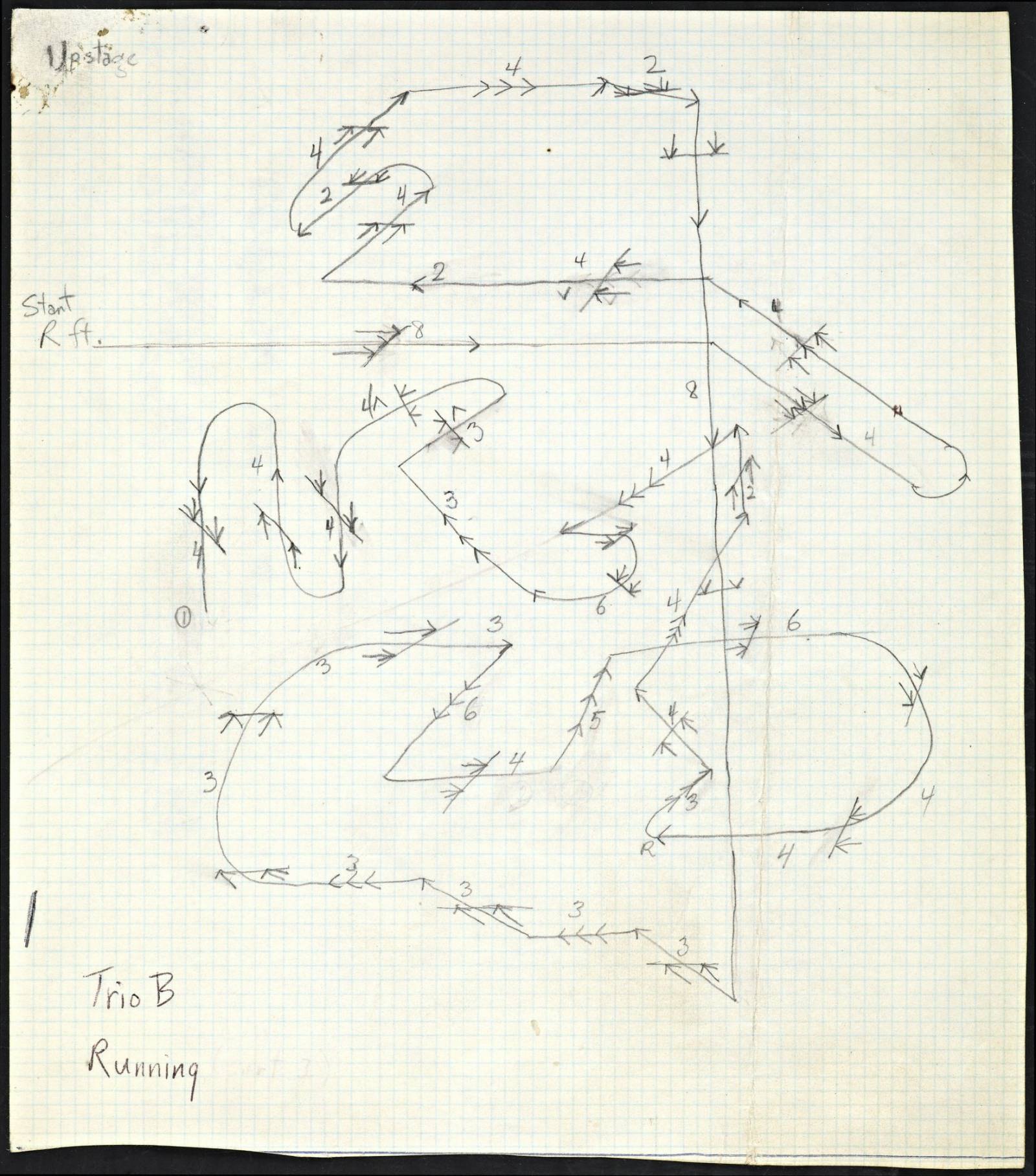

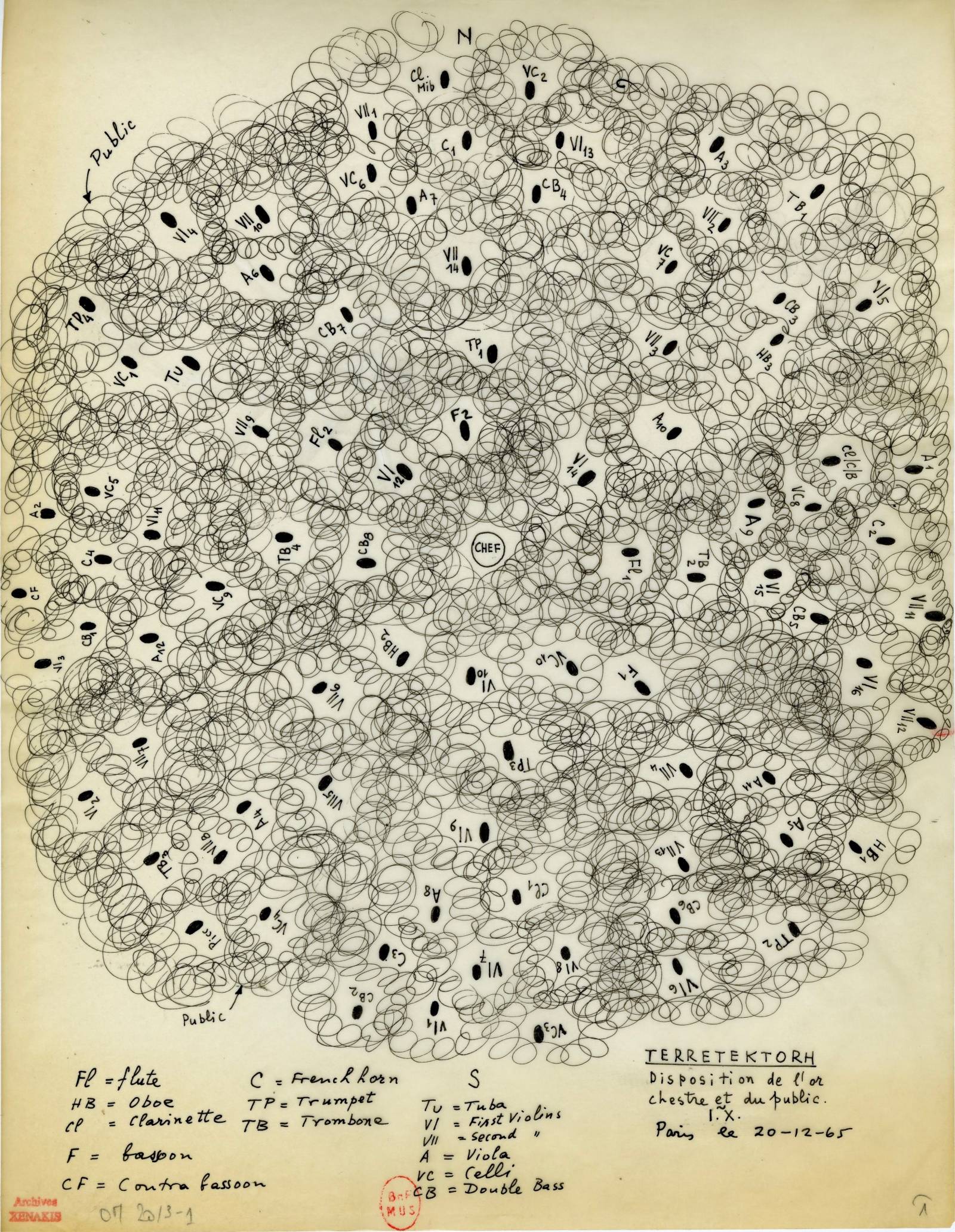

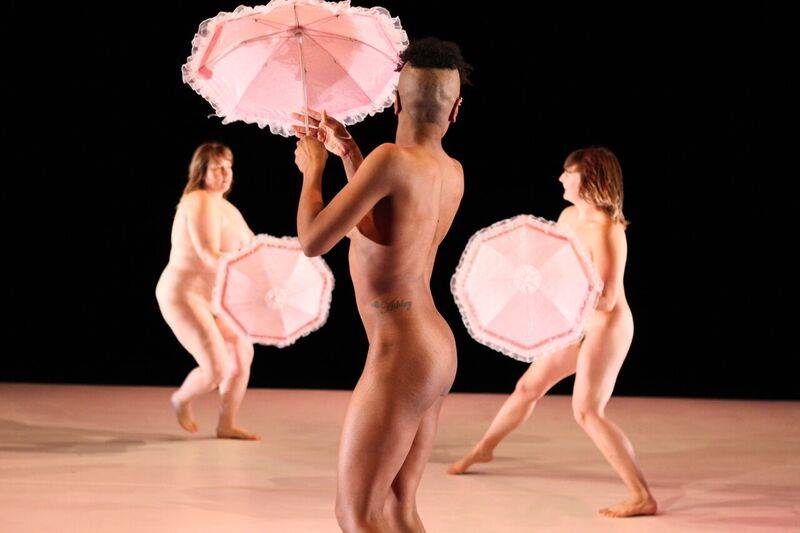

I do seek to create artworks that invite and engage people to experience them with an awareness of life’s ephemerality. As a composer I am working in a form that is particularly well suited to this goal: it is necessarily time-based and can detach itself quite nimbly from symbolic interpretation and from overt references to ideas outside the artistic moment itself. I often try to heighten these qualities of the musical encounter by creating site-specific compositions. When placed outside a traditional concert hall and in transient public spaces, music can come from all different sources around and within a space. My listeners—many unwitting, who simply happen by—are given no guidance as to how to encounter the work (no chairs, no prescribed listening area). I believe that such conditions can further heighten the listener’s awareness that what she or he is experiencing is unique to him/herself in that very moment, an event that cannot be replicated or sustained.

I began exploring this kind of individualized listening by moving instruments around concert halls that had fixed seating. Later I took the work outside in my piece Chance Encounter (2007–), co-conceived with the soprano Susan Narucki). The piece begins with a single musician (a cellist) playing in a public space and gradually grows as an entire chamber orchestra and a soprano soloist join in two groups, forming a dialogue across a distance of a short city block, then dissipates again as the musicians leave the site one or a few at a time. I greatly expanded on the enhancement of individualized listening through the placement of musical instruments in public space in my recent large-scale works for hundreds of musicians in airfields that are now public parks, Tempelhof Broadcast in Berlin and Crissy Broadcast in San Francisco (both 2013). In these works multiple orchestras, bands, and choruses gradually dispersed outward across vast spaces, such that they can no longer all be heard by any one person, stationary or in motion.

As an artist I find that our field’s strong emphasis on access (widened through online portals) and documentation (always needed in order to disseminate the work) is sometimes at odds with the artistic impulse to emphasize ephemerality. The challenge becomes how to enhance access, not only on-site but also through technological media. How can we create access in ways that multiply the number of unique experiences of the artwork without flattening the experience or filtering it through one lens? If the value of an artistic experience is that it is truly gone once it has been achieved, how (and even why) does one adequately document such work? Should one try? My directive to my own videographers is always to focus on documenting the feeling and the community that the work is creating. I believe that it is most important to capture the arc of this unfolding—among audiences, unwitting listeners, and participants—rather than to try to document some elusive notion of the “work itself.”

My inquiry into public-space work began in 2006, with Chance Encounter, and I found myself in company with the phenomenon of flash mobs. Groups like Improv Everywhere (responsible for Frozen Grand Central, for example) were at the forefront, and now the organizers of flash mobs are too numerous to mention. The most elegantly designed of these works can indeed bring a heightened sense of ephemerality to people in the midst of their daily lives. I can see why this kind of impulse in art making and event making is in the air. Our wired lives exist in a state of saturation—surplus mediated access and documentation, one might say—and there seems to be an increased need for us to have experiences that truly are ephemeral, to bring our awareness into sharp contact with the moment.

Even when we are working in a format designed to be a permanent document, as in my opera created expressly for broadcast and online media, Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser (2015), director Charles Otte and I are committed to capturing actual performances on camera, eschewing the usual media tools one uses to “cheat” (over-dubbing, lip- or bow-syncing) and testifying to that fidelity to the moment by training the camera closely on the hands of Kronos Quartet violinist David Harrington, for example, while he plays passagework impossible to feign for a camera.

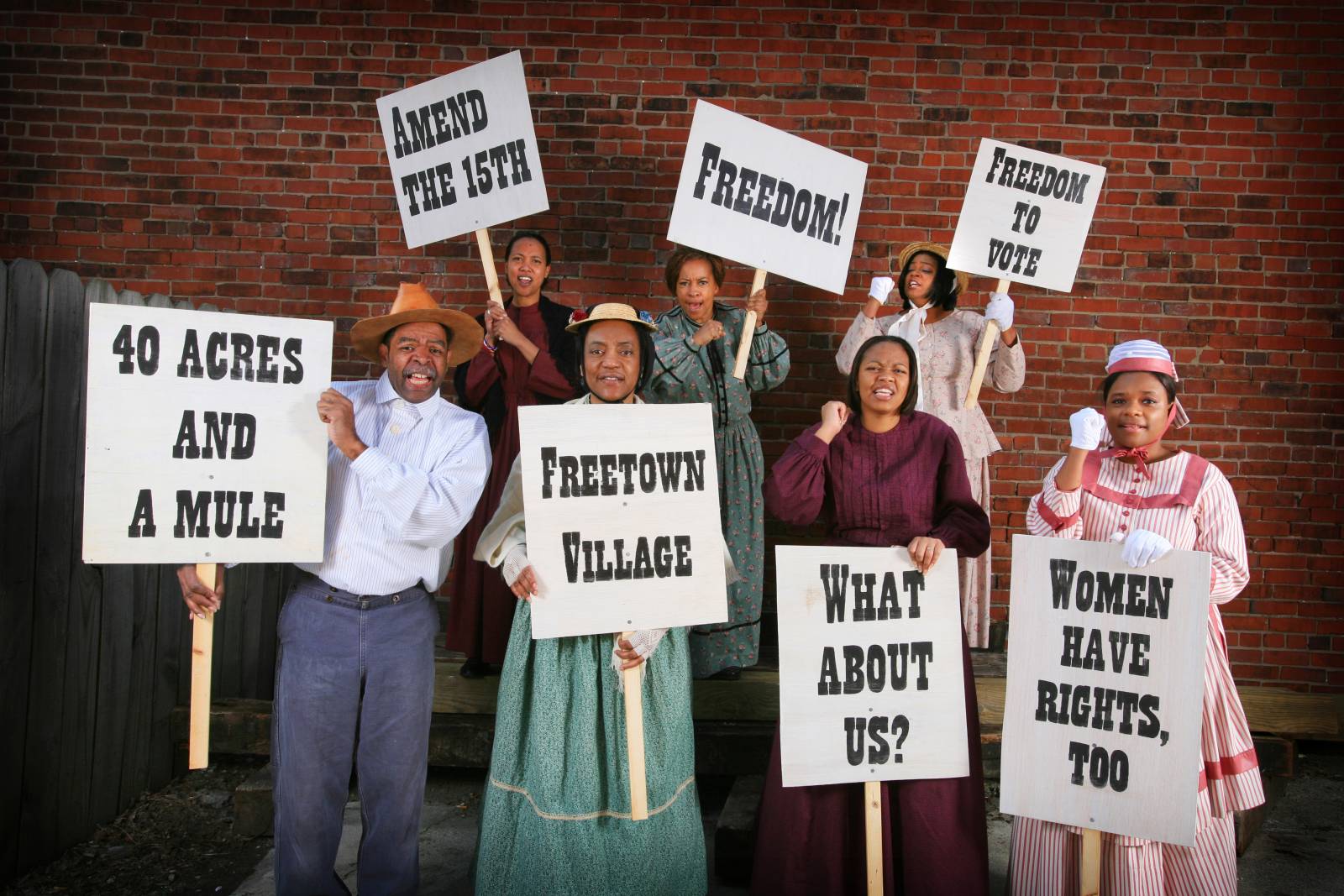

Some other exemplary artists whose work I feel heightens our awareness of ephemerality are working not in music but in sister time-based mediums. I find the film work of Adam Magyar—captured by extremely high-speed cameras mounted on subway trains in New York, Tokyo, and Berlin—especially beautiful. We Players in the San Francisco Bay Area mounts site-specific productions of classic plays (like the five-hour Odyssey in Angel Island State Park in 2012, in which the audience was shepherded around the island, within the narrative); the group creates memorable experiences in a deeply physical way that is impossible to document. Other composers whose work makes the ephemeral act of listening more personal include John Luther Adams, based in Alaska, and Alvin Curran, an American based in Rome. And of course musical virtuosity itself, especially when it is in an improvised form (including jazz), often brings one a heightened sense of being in the presence of something that is truly alive only in its native moment.

For Further Reference

Chance Encounter, 2007–. Composed by Lisa Bielawa; co-conceived by Bielawa and Susan Narucki. www.lisabielawa.net/chance-encounter and www.chance-encounter.org.

Airfield Broadcasts, 2013 (Tempelhof Broadcast in Berlin; Crissy Broadcast in San Francisco). Composed by Lisa Bielawa. www.airfieldbroadcasts.org.

Improv Everywhere. improveverywhere.com.

Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser, 2015, a project of Grand Central Art Center, CSUF, and KCET. Composed by Lisa Bielawa; libretto by Erik Ehn; directed by Charles Otte, featuring 16-year-old soprano Rowen Sabala. www.operavireo.org.

Adam Magyar, Stainless, 2010–11. www.magyaradam.com.

We Players, www.weplayers.org.

John Luther Adams, Inuksuit, 2009. johnlutheradams.net/inuksuit.

Alvin Curran, composer and sound artist. www.alvincurran.com.