Dabbler, astronomer, amorous, Frenchy. Across fields, amateur is opposed to professional, which is disciplinary, situated, ranked, skilled, and compensated. Amour, less so.

Masculine. Perhaps the name Amy could be used colloquially as a feminizing Anglicization: “Not only a software developer but an amy archaeologist as well.”

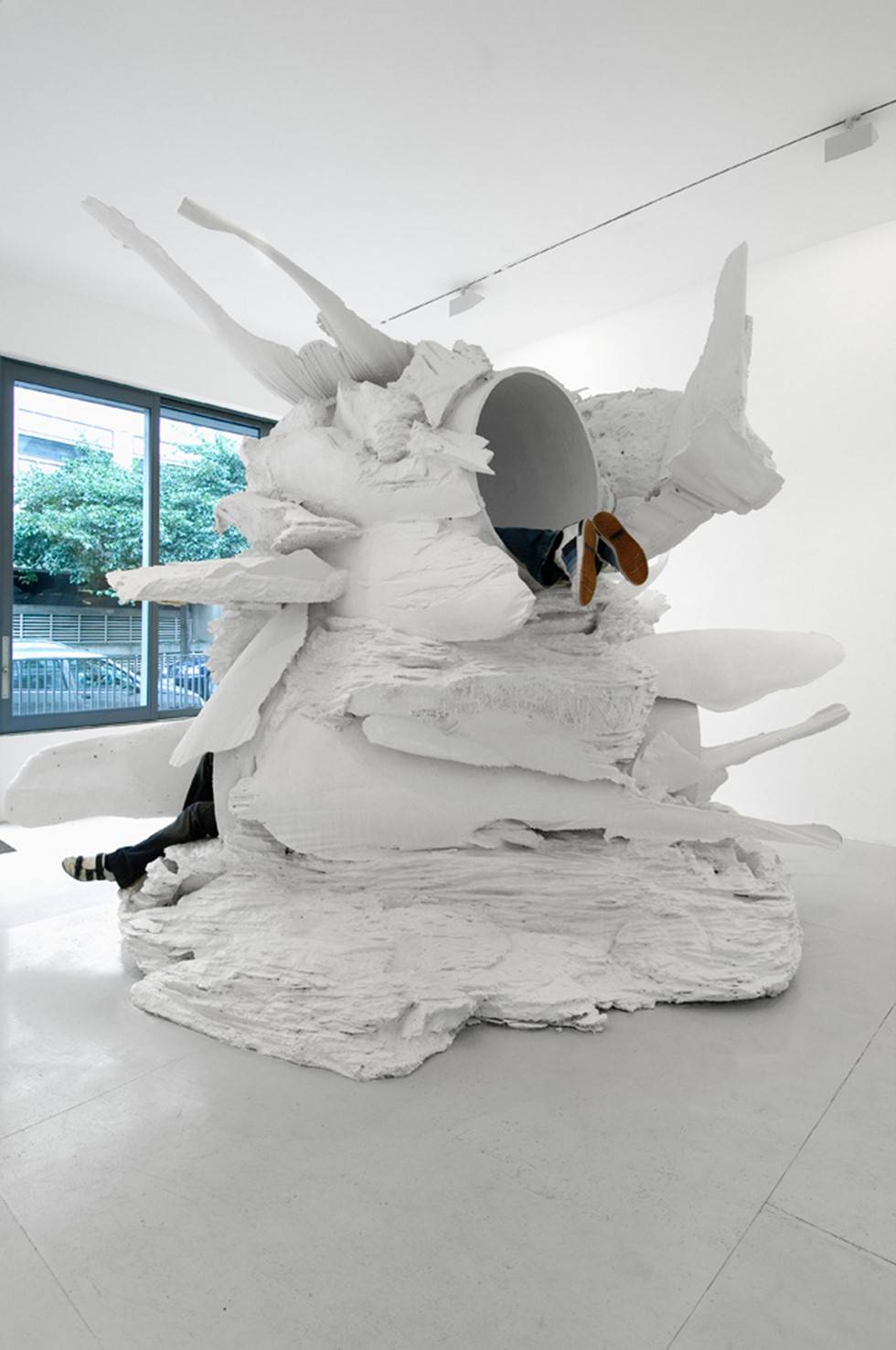

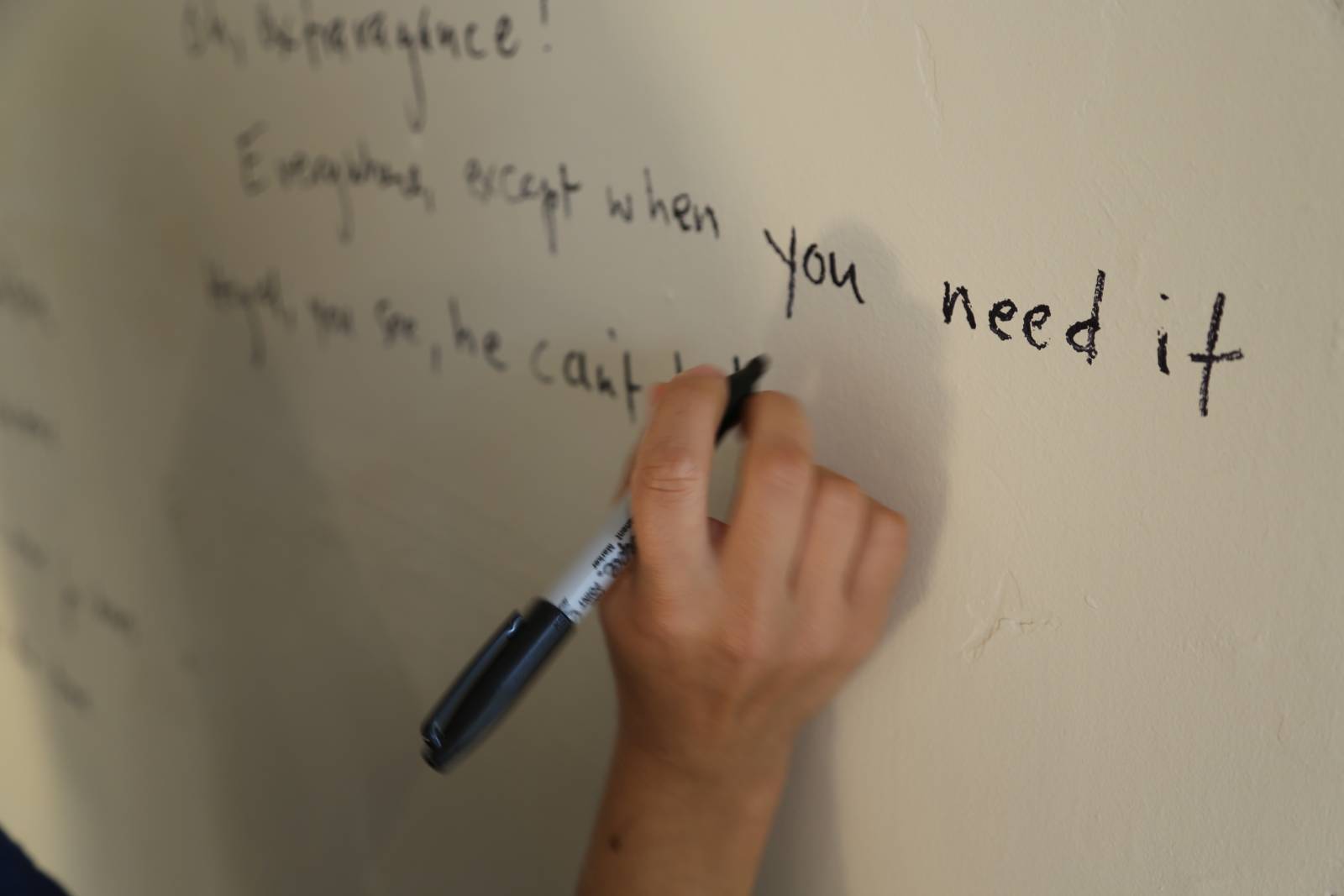

In art: an emotional de-skilling. Art-historically, a dismantling; liberated from the coercive mastery of production and style, the elitism thereof. Rejection but from a place of love.

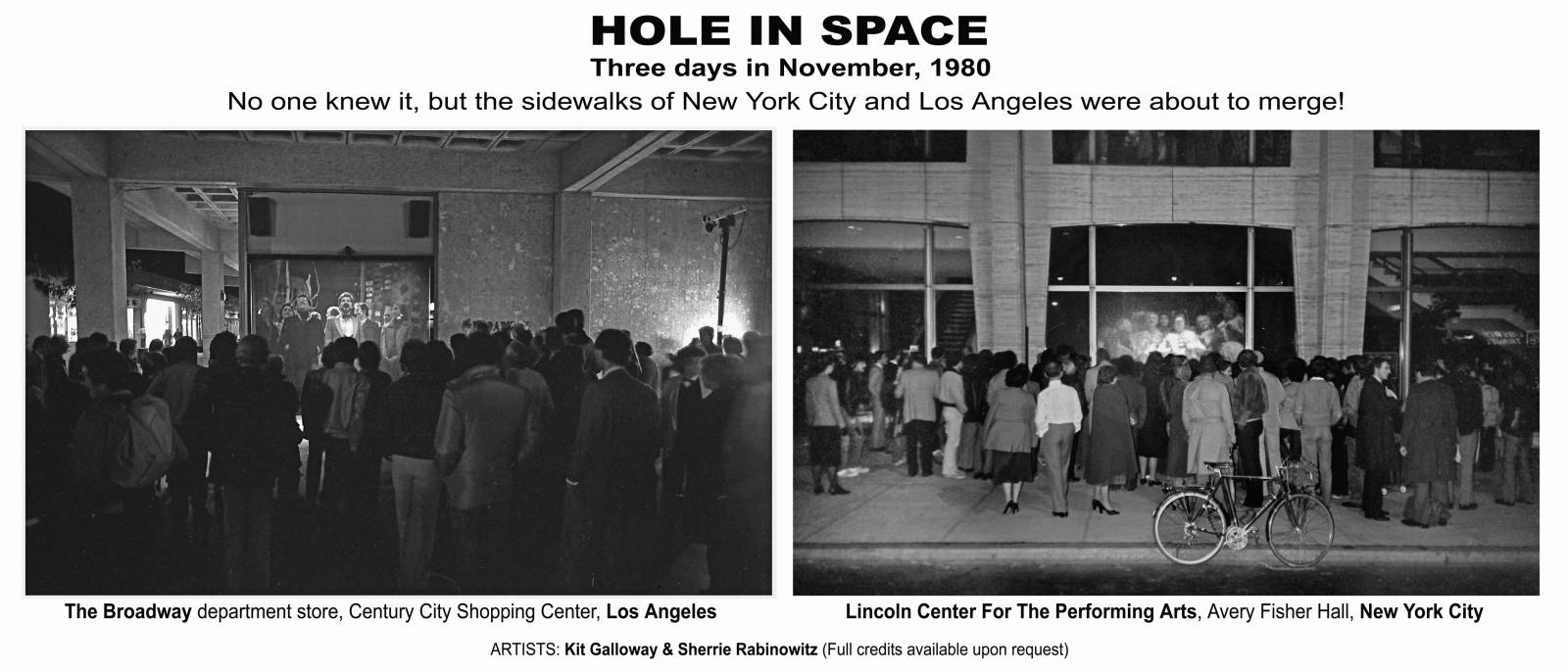

Amateur Night at the Apollo: skill still. “Everyone on this stage is an amateur, everyone deserves a fair chance. We judge them only on talent.” The amateur talent uses skills of the profession and may aspire to join the profession. Lacking access, she has not transformed talent to commodity and may yet sing for love alone, though she deserves money.

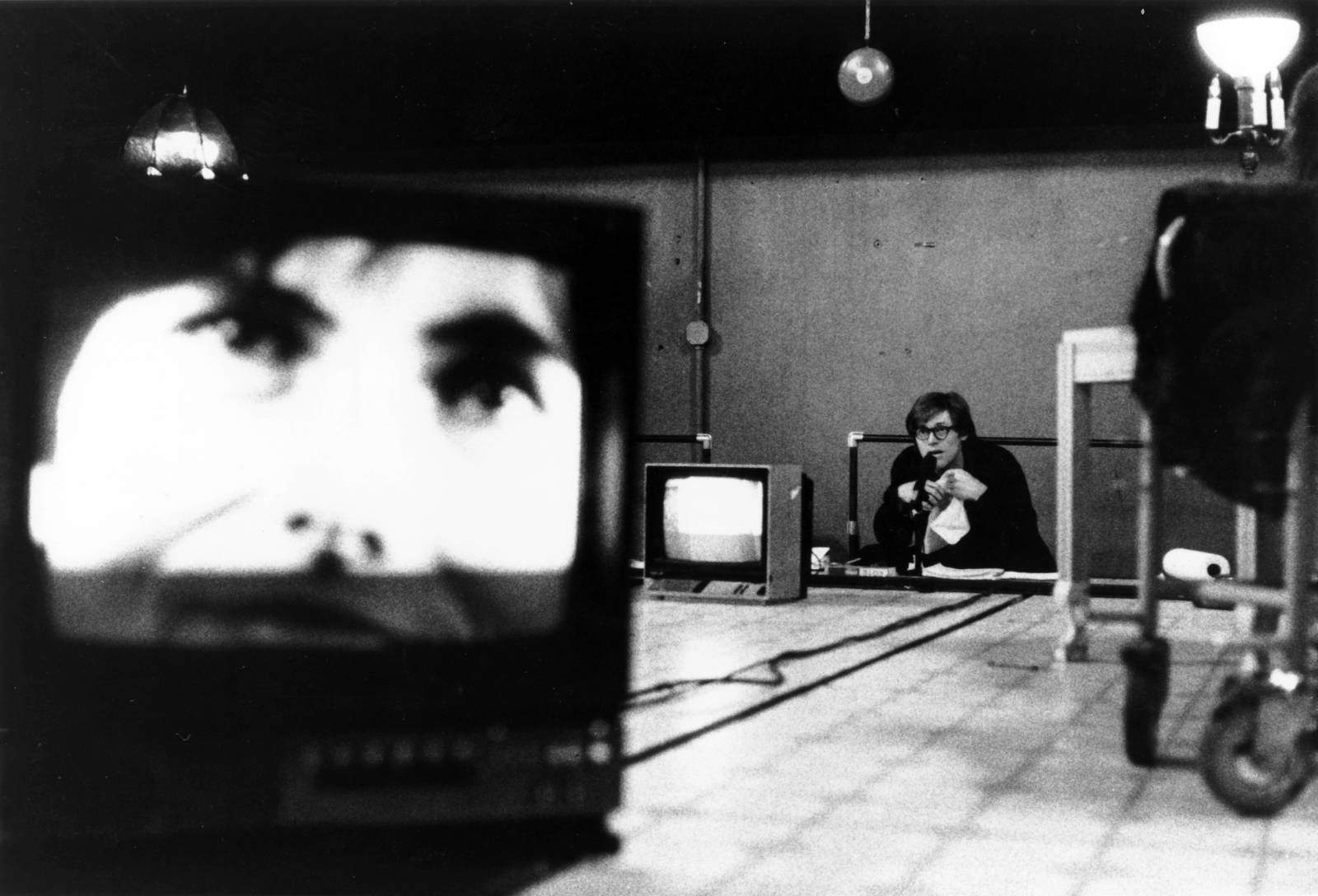

In beholding both the skilled and the de-skilled amateur, the spectator, or viewer, is potentially untethered from her consumer situation, against which the object’s labor time, use value, and exchange value have been standardized and regulated, or if not, then she or he is having some differently ordered experience.

The skilled amateur performer, who makes reference to disciplinary quality, faces now a speaking spectator: not a supplicant viewer but a laughing judge whose pleasures interact with the performance. The emotionally de-skilled artist suspends hierarchies of taste and value, asking her viewer to reevaluate inherited criteria that produce quality and interest.

AMOUR: c. 1300, “love,” from Old French amour, from Latin amorem (nominative amor) “love, affection, strong friendly feeling” (it could be used of sons or brothers, but especially of sexual love), from amare “to love.” The accent shifted 15c.–17c. to the first syllable as the word became nativized, then shifted back as the naughty or intriguing sense became primary and the word was felt to be a euphemism.

LOVE: Old English lufu “love, affection, friendliness,” from Proto-Germanic lubo (Old High German liubi “joy,” German Liebe “love”; Old Norse, Old Frisian, Dutch lof; German Lob “praise”; Old Saxon liof, Old Frisian liaf, Dutch lief, Old High German liob, German lieb, Gothic liufs “dear, beloved”).

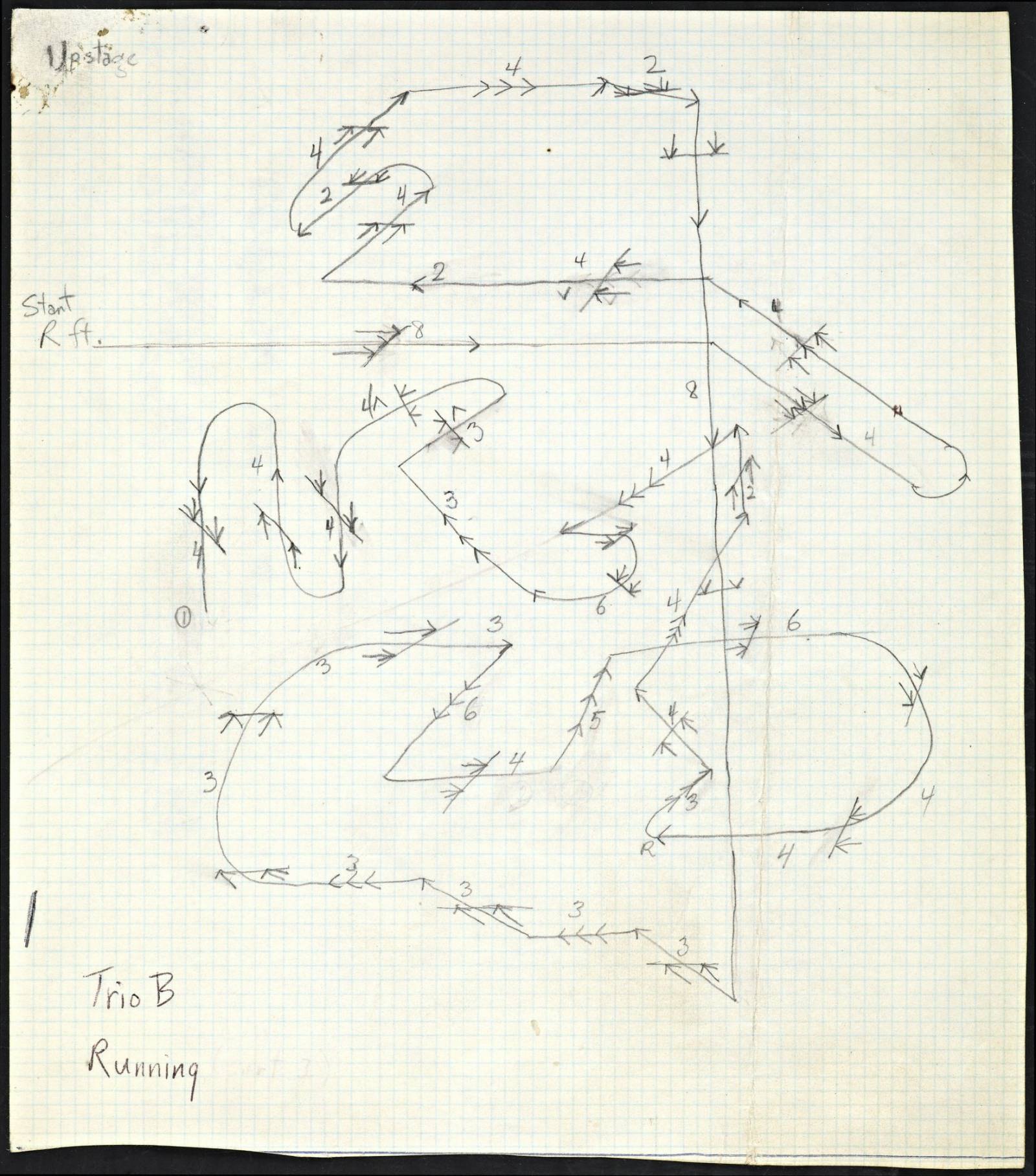

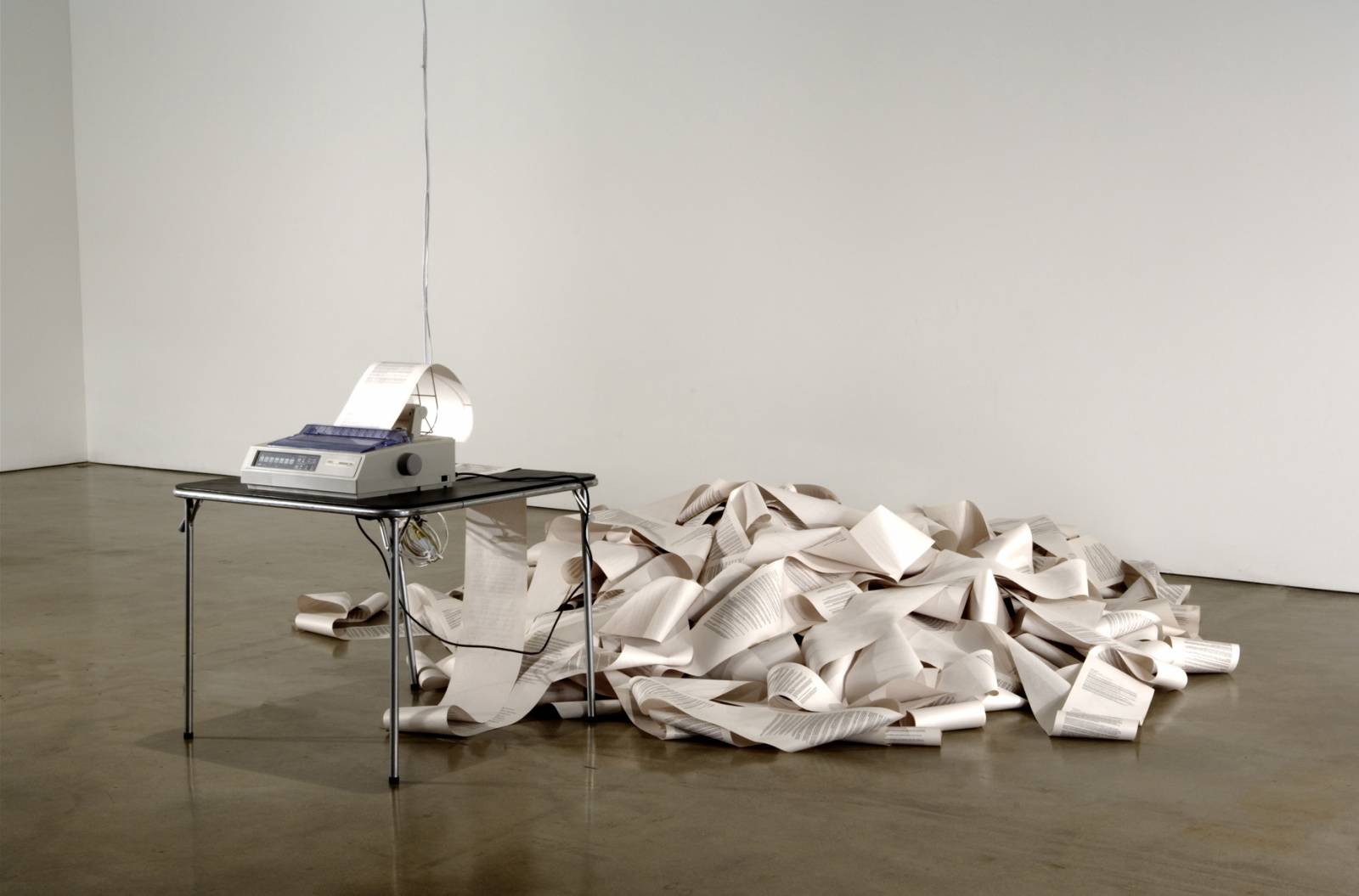

Years ago, in an interview, my collaborator and longtime lover, Alexandro Segade, described the work of our performance group, My Barbarian, which is made up of us and Jade Gordon, our collaborator, whom we love, as that of “dedicated amateurs.” But that was a slip, I think, or he was just trying something out. An amateur move? We’ve had some difficulty with a set of terms that developed around the time our work began to circulate, in the 2000s, when everything was just too much, the wars and the wealth and the Christianity and Texas and all. There has always been a calculated provisional quality to our work, which has as much to do with strategies for dispelling the illusionist illusions of theater and critiquing the mythic masteries of visual art as it does with understanding our positions within these fields; we are all variously and deeply trained and are pretty good at what we do. Much of our work has pointed to class status and enacted class anxieties, and the position of the artist has sometimes appeared to us as an amateur elite class, given the provisional access one has to travel, to refined locations, to food, high-end discourse, and actual wealthy people. But as performers we find our publics to be rather broad, and these may include children, nurses, criminals, schoolteachers, assistant curators, and the homeless. Our intentional dismantling of hierarchical orders—even in the very act of collaboration, which diminishes genius status—may sometimes read as a kind of amateurism.

It may be connected to failure, another term that circulated around this time. A great honor of our lives has been the consideration of My Barbarian’s work in José Muñoz’s book Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. When José visited us in Los Angeles to discuss queer failure as a utopian tactic, we admitted that none of us are trying to fail; we three are rather aspirational, and while we understand the concept, it’s not the best description of our work. When the book came out, we found that the author, whose astounding generosity nearly matched his brilliance, had coined a new term for us, “queer virtuosity.” It operates pretty much the same as queer failure. But through the magic of queer time, statuses are fungible, the failure becomes the virtuoso, and the amateur becomes the expert. Queerness is one of those notions that revises the ranked and ordered structures through which class becomes legible. These are the elisions, negations, and inversions that reanimate terms for us, allowing us to reevaluate those things that are too much and those that are not enough.

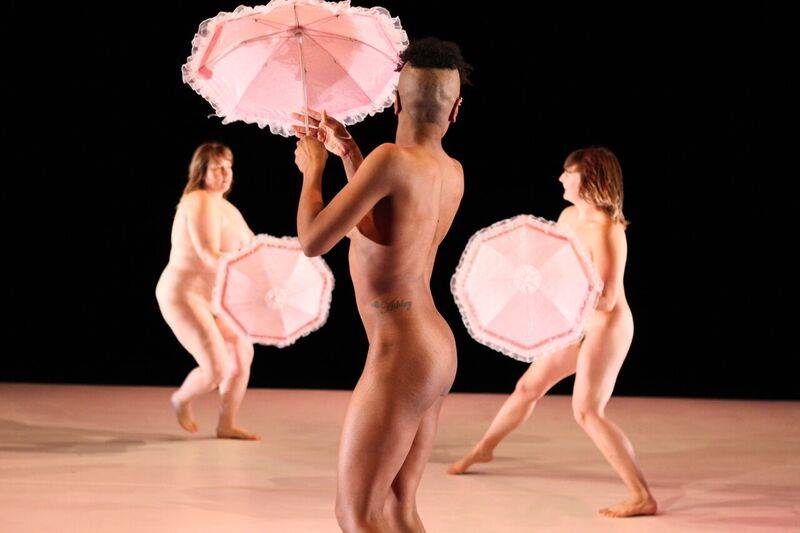

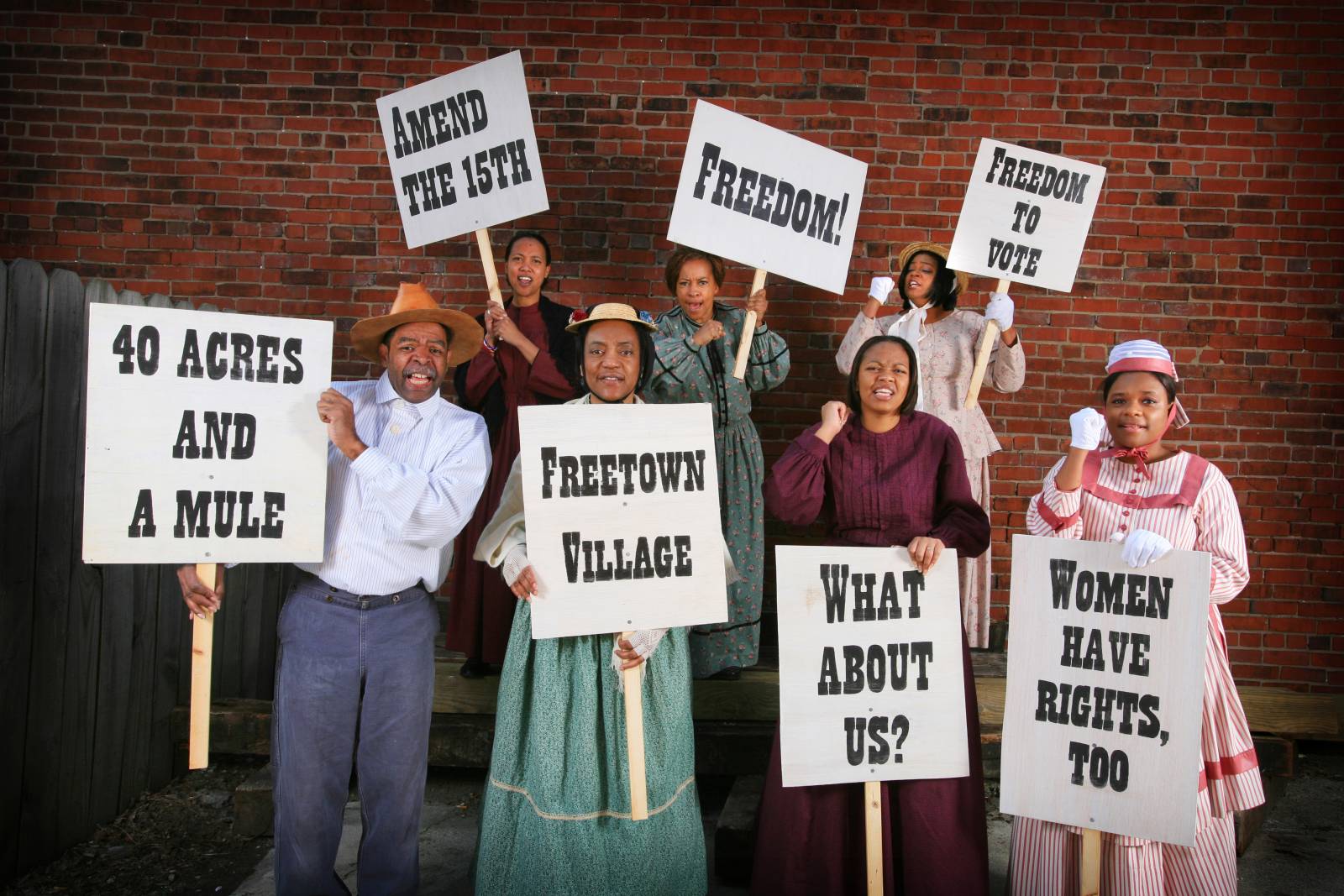

Finally, let’s acknowledge that the dropout, the slacker artist, the beatnik, and the fuckup are all positions that reject privilege, a rejection predicated on access to privilege. These terms are steeped in class and are particularly racialized in the American context, in which blackness has been associated with all sorts of compensatory virtuosity. Consider the differences between Sylvester and the Cockettes, who have been influential on my own work. The former was a talented African American performer who aspired to professional success despite his permanent outsider status, engendering a radically virtuosic expressivity, while the latter collective was made up mostly of adventurous young white people who rejected security in favor of anarchic freedom and cultivated a radically transgressive form of amateur theater. Their projects were not the same, though they did work together across differences for a few extraordinary and provisional years. While embarking on all kinds of unauthorized collaborations, the intentional amateur often chooses her liberation from privilege. Meanwhile, Amateur Night at the Apollo, with all of its extraordinary aspirations, has no time for fuckups.