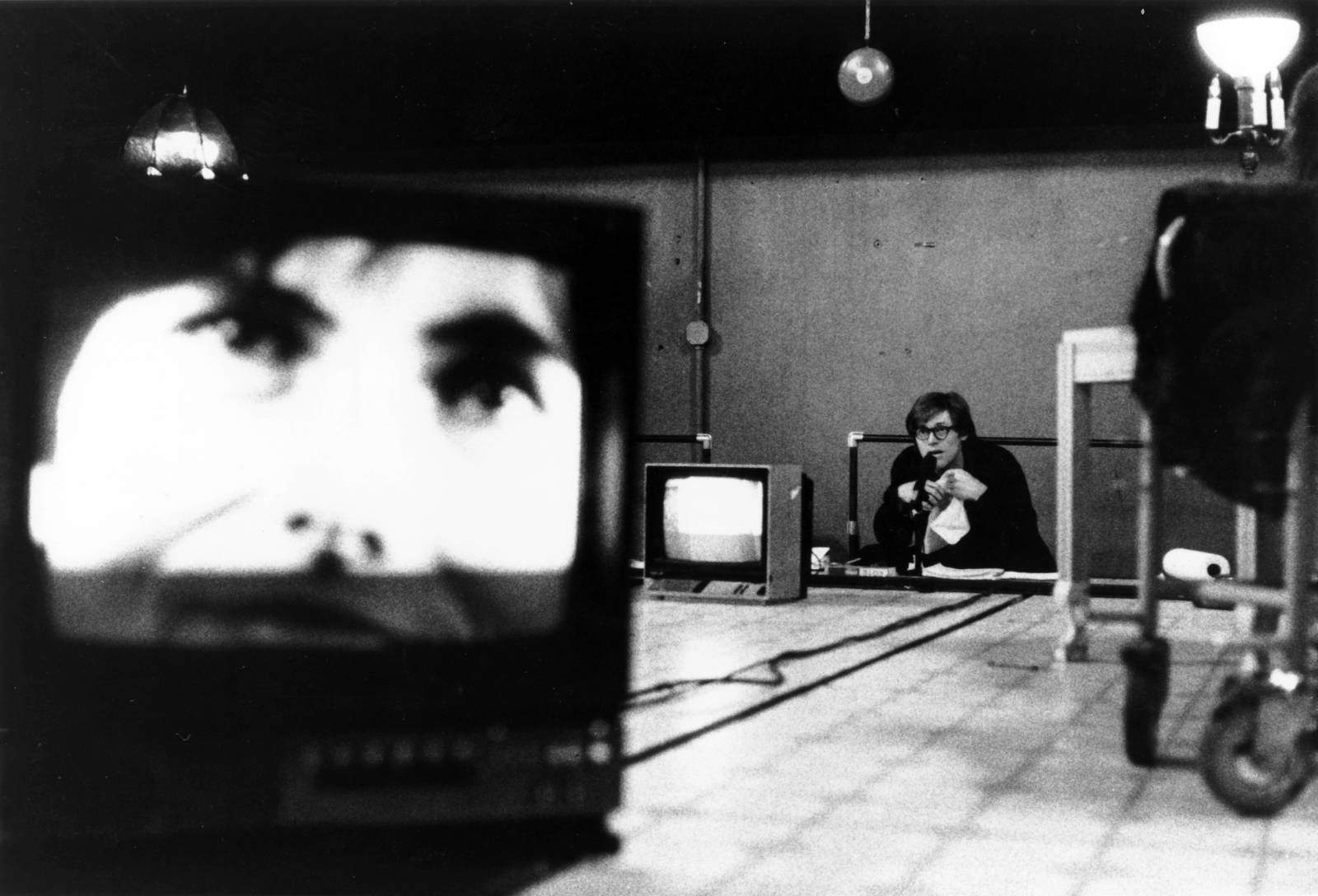

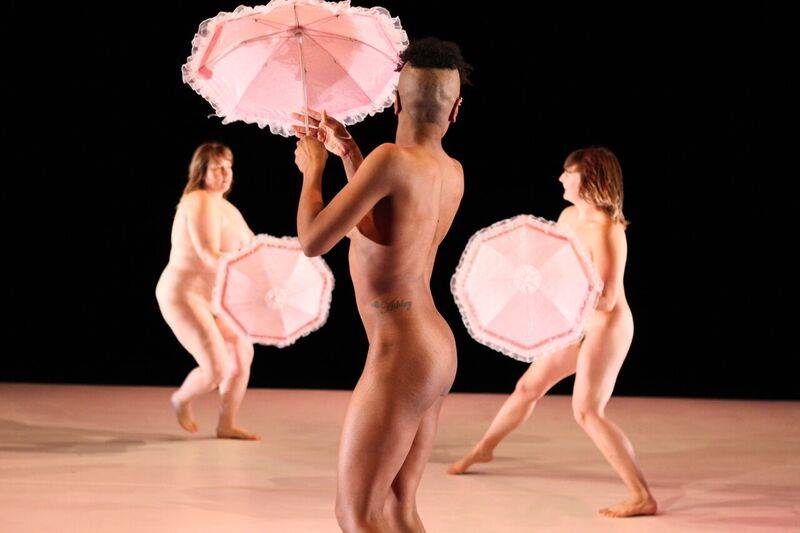

Theater provides the unique experience of watching the body in real time, inside a story. Because it is live, theater allows us to get closer to one another. The melodrama, the kitchen-sink drama, the Restoration comedy, the avant-garde play, the musical comedy all have something separating them from television, for example.

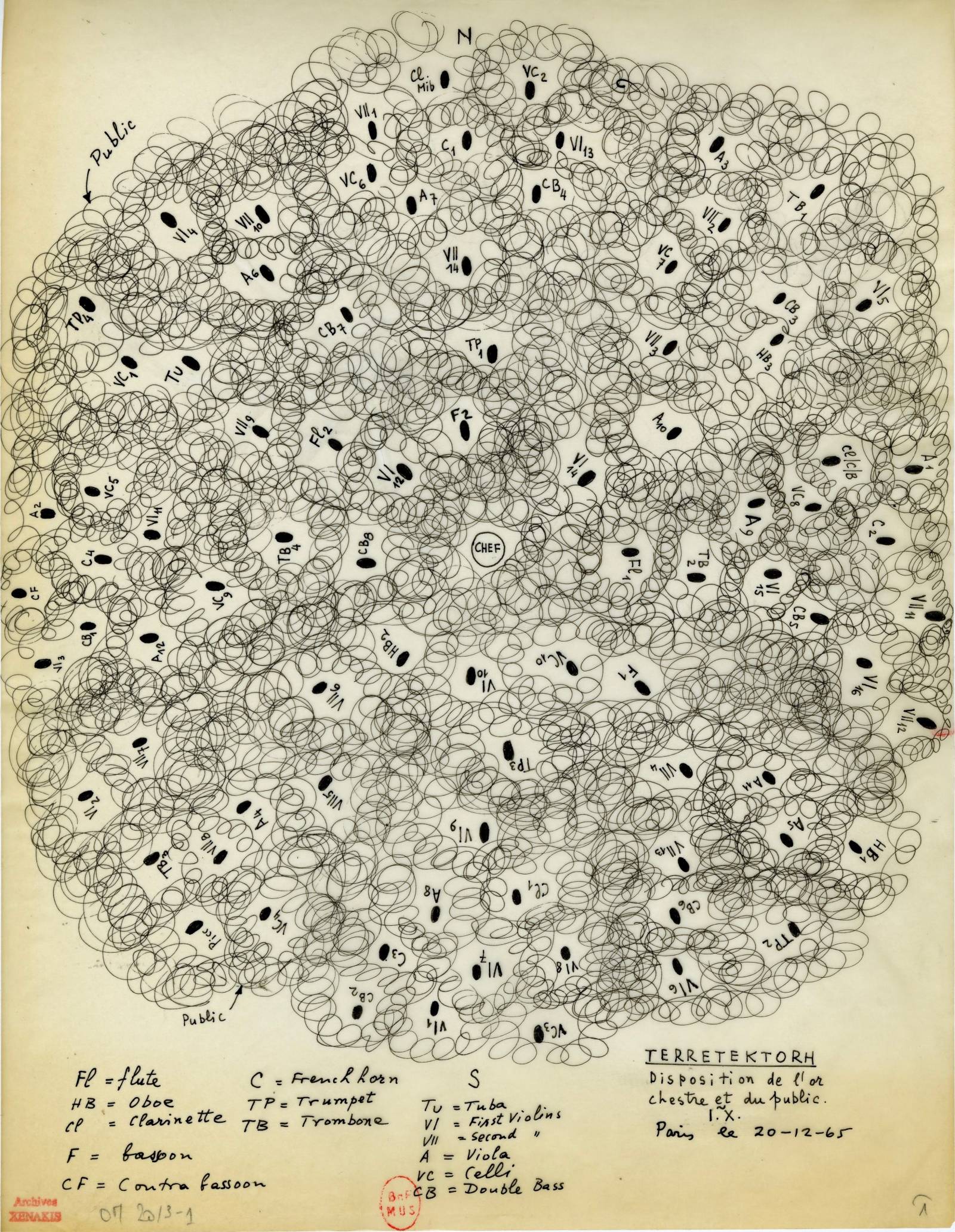

In theater we can’t subordinate this face-to-face reality to our will. There is reality occurring in front of viewing eyes, and the combustible mix of reality with the action on stage is enticing, electric, an alternating current.

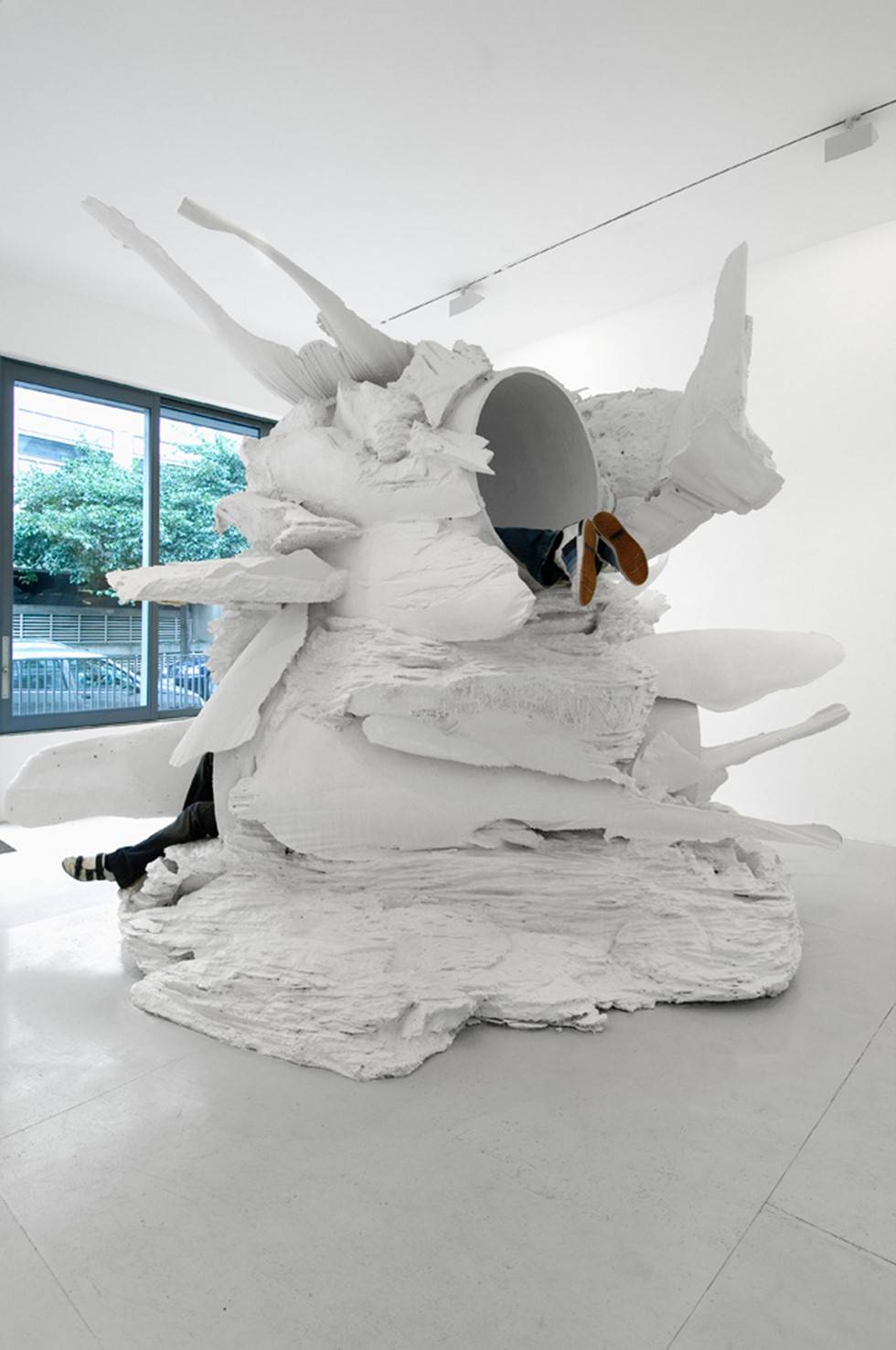

The spectator in the theater watching the stage is presented with a question: What is this thing happening before me? It’s real and it’s fake—this person, this set, this room, this story.

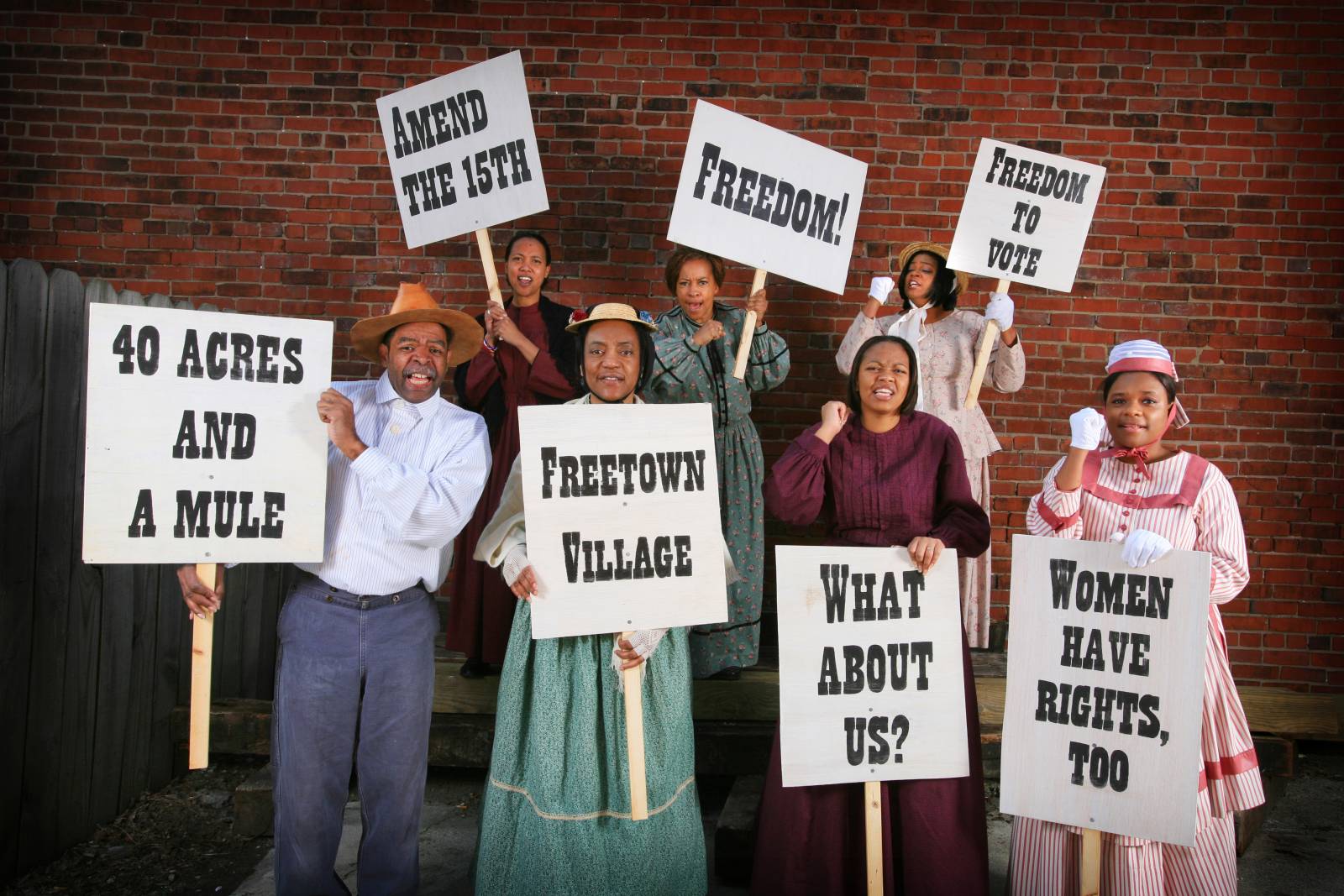

There is accountability on both sides of the footlights. Theater fosters community and maybe simply is community, put into relief.

You, actor, are the gateway to these encounters. And no matter how long a writer works on the writing, no matter how impressive the staging is, the actor on stage will have the final say.

You, actor, are the spark and the current that give words life, you are alive in the room before us, in the present.

You, person before us, are interesting. You are molecules and spirit that cannot be repeated. Remember this going into any audition, rehearsal, or performance.

Acting is a working paradox. You step onstage, and contradictions fly at you: give versus take, real versus fake, speak versus listen.

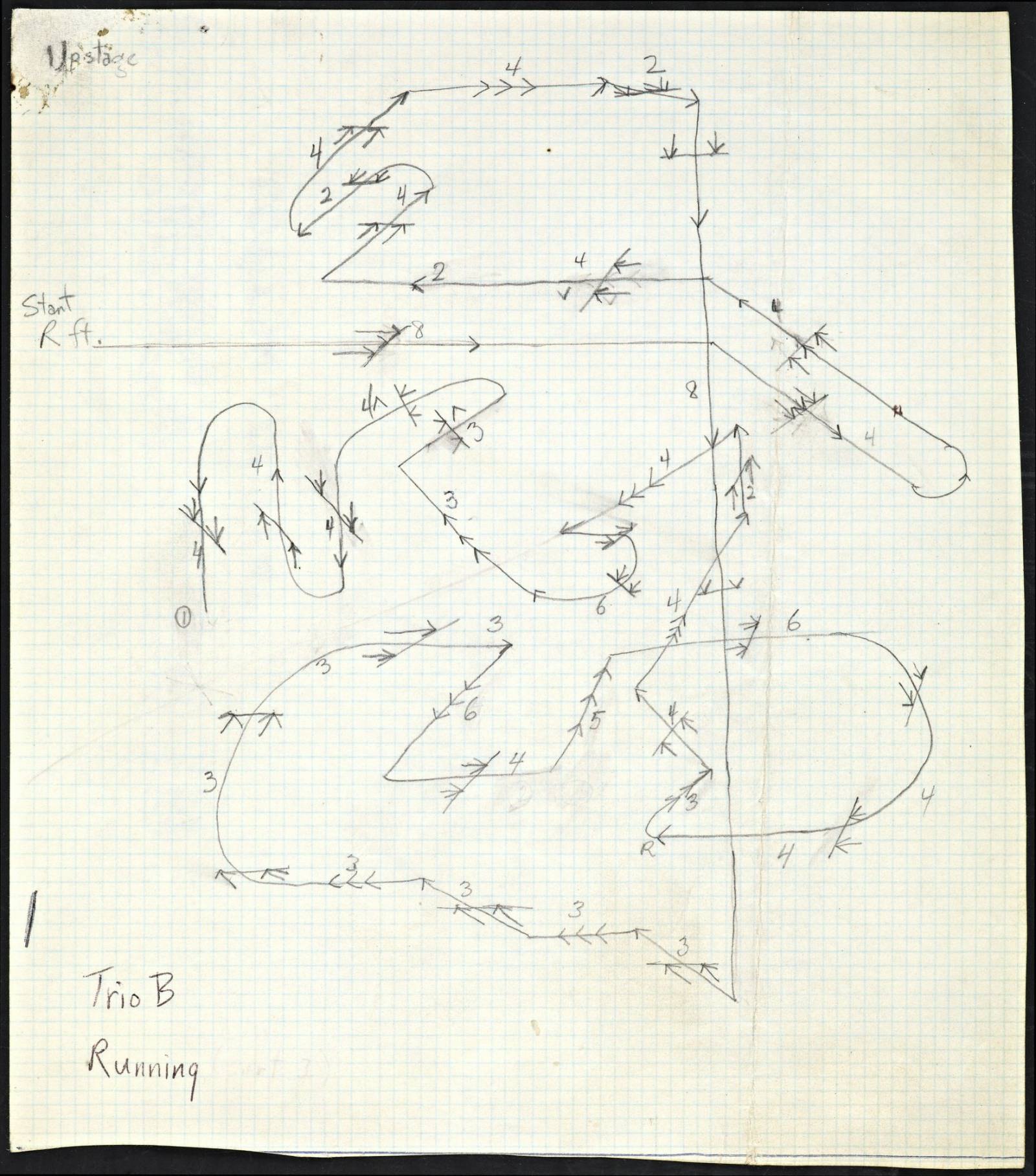

Actors share a stage locked inside the stasis of none-shall-lead-none-shall-follow and the need for the action of moving forward through events.

You are onstage and in a scene with another person, and she forgets her line. And right there, just in that sliver of a moment, you have a moment of known and unknown, notions of professional and amateur, right and wrong, of actor and character, of staying and continuing. And you may not like the thing that’s happening, but it’s happening.

A paradox also stems from the predicament of being in two places at the same time. The body grapples with the two realities: the room and the story.

You are the actor, and I am the spectator. You step on stage. I sit in the house.

You face an audience and open your mouth to speak. Fear will be there if you're alive. It's a healthy feeling. It feels like humanity. There is, of course, no shortage of feeling up here. It is an extreme act, unusual, testing you in unparalleled ways. It speaks to the core of who you are and why you do what you do. The challenges exist in life but become acute in a theatrical situation.

The images, feelings, and desires that cross your path as you endeavor to move through a piece are unique—the home of your youth, your parents, your family, your hometown, your street. But whatever impulses are generated from the delicate constructions in your mind and soul have to be measured against the moment, the ephemera, if you will, of many people; you, your fellow performers, the audience. What you see in your mind will never be known to anyone but you, and yet you are essential.

The audience sees what isn’t there; the actor sees what’s there. Some see to learn. Some see to confirm. Assume the former. It might keep you humble, attentive, and active in your mind. Your fantasy, let it be. Let the image of it be, and let it go. Let it be a thing that supports you, whether you hold on to it or not.

You are the actor. You see an open flat field of green in the Appalachian Mountains where the local school holds soccer games. The sun is setting just over the westerly hills, causing the parents on lonely bleachers to shield their eyes with flat hands to watch their children. This smattering of good parents, at attention with good posture and understanding eyes. This golden, American moment, frozen in your mind. You strive for control over what you’ve seen. But time passes, and what you felt or saw fades. Longing must be about feeling a lack of access. Access to do what you want, to go where you please, to have a life before you to live.

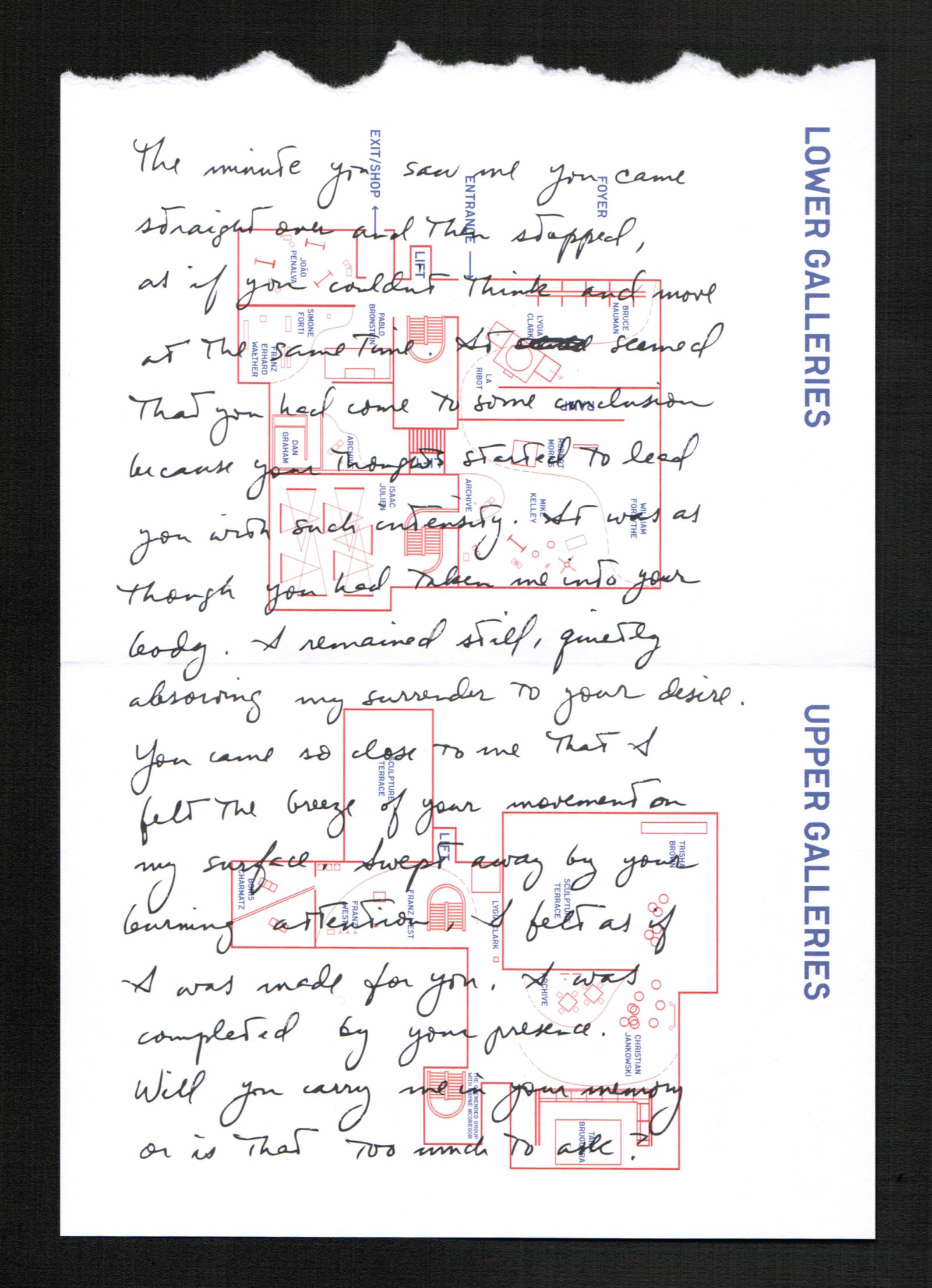

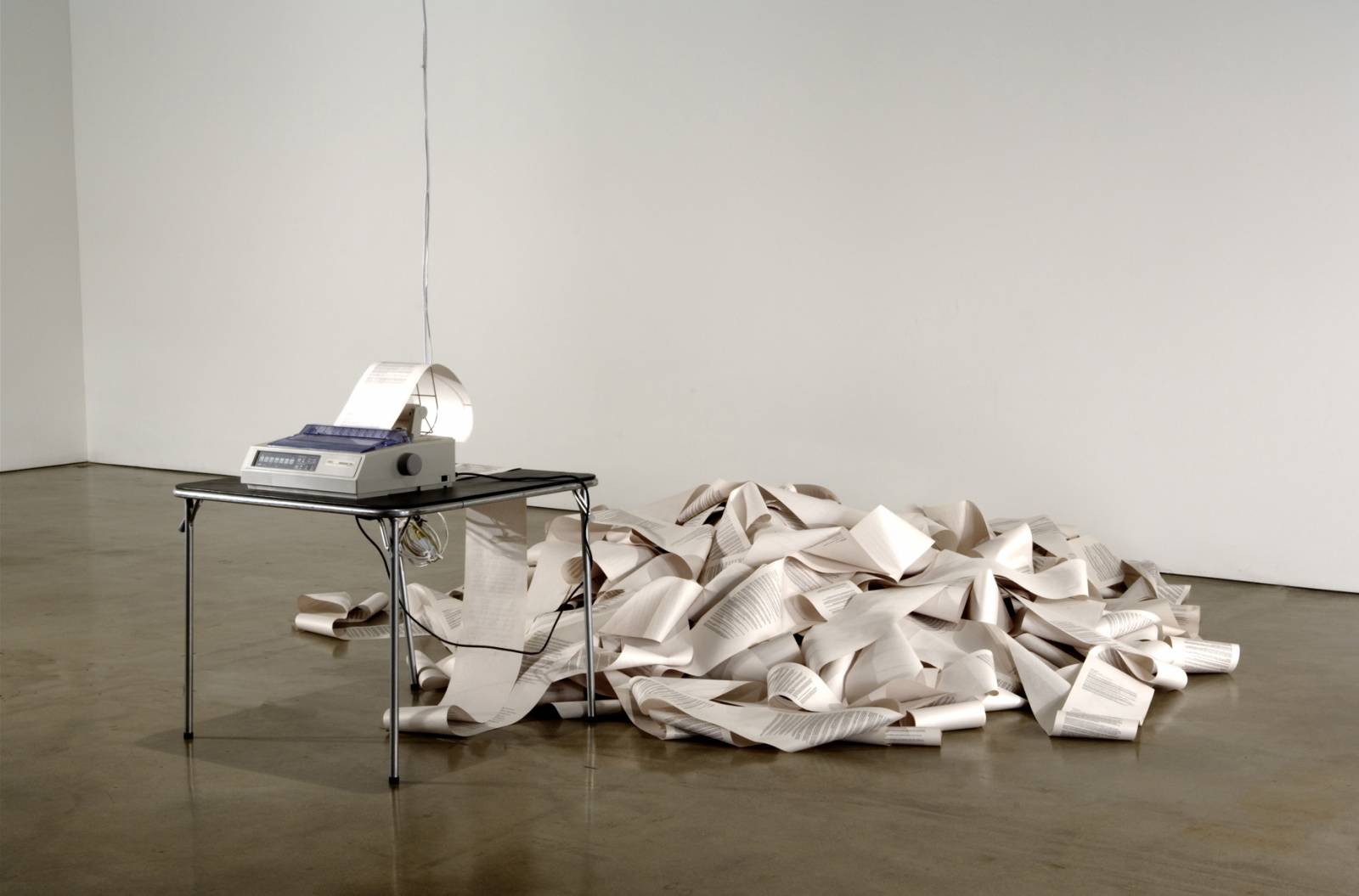

I am the spectator. I invent as I see the human body in its entirety. My eye does the edits. The cuts. Hand on cup. Lips. Sleeve. Face. Now the eyes. Now the legs, the black stubble. Look at those pants. They’re chinos. The soles of the shoes, Vibram rubber. All gets seen, and I want to see it. I cut for an idea; I cut against. I am an active part of the equation, and I want latitude. Theater lets me look. I compare and measure my reaction to and with those around me. I bring my life and theater-viewing history to that moment; the history of viewing I cannot change. And I anticipate based on what I have seen. I am witnessing two stories, one of the play and one of the room. The tension between the two stories creates friction. The friction is reconciled in my mind as I watch it.

You are the actor. Pursue potentially unreachable things with humility by tapping into eternal currents. Accept yourself and the history you bring. There is no one else occupying the space you find. You don’t need permission from anyone. A poem unfolds every night. We fall into the service of it. The poem is not the writing. The poem is us. Let the poem lead you; we go together like sad tears and inclement weather. Let the poem unfold. Watch and follow it for clues. Examine what happens.

There is the open stage.

Wispy floating toward obscurity, and seeing it, from midair, dancing, wispy, cloud-like, undulating, blown further toward it, seeing it, almost pulled into it, and then turned, having witnessed it, felt it.

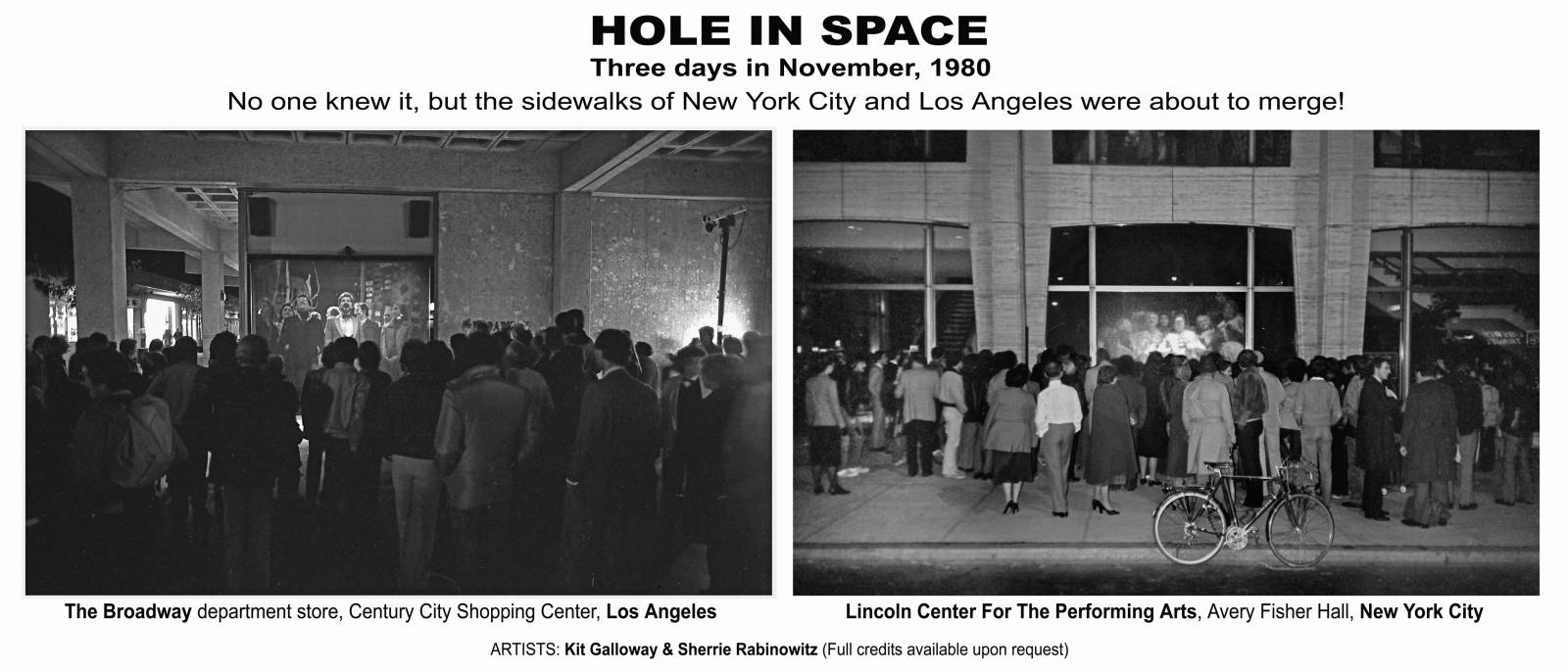

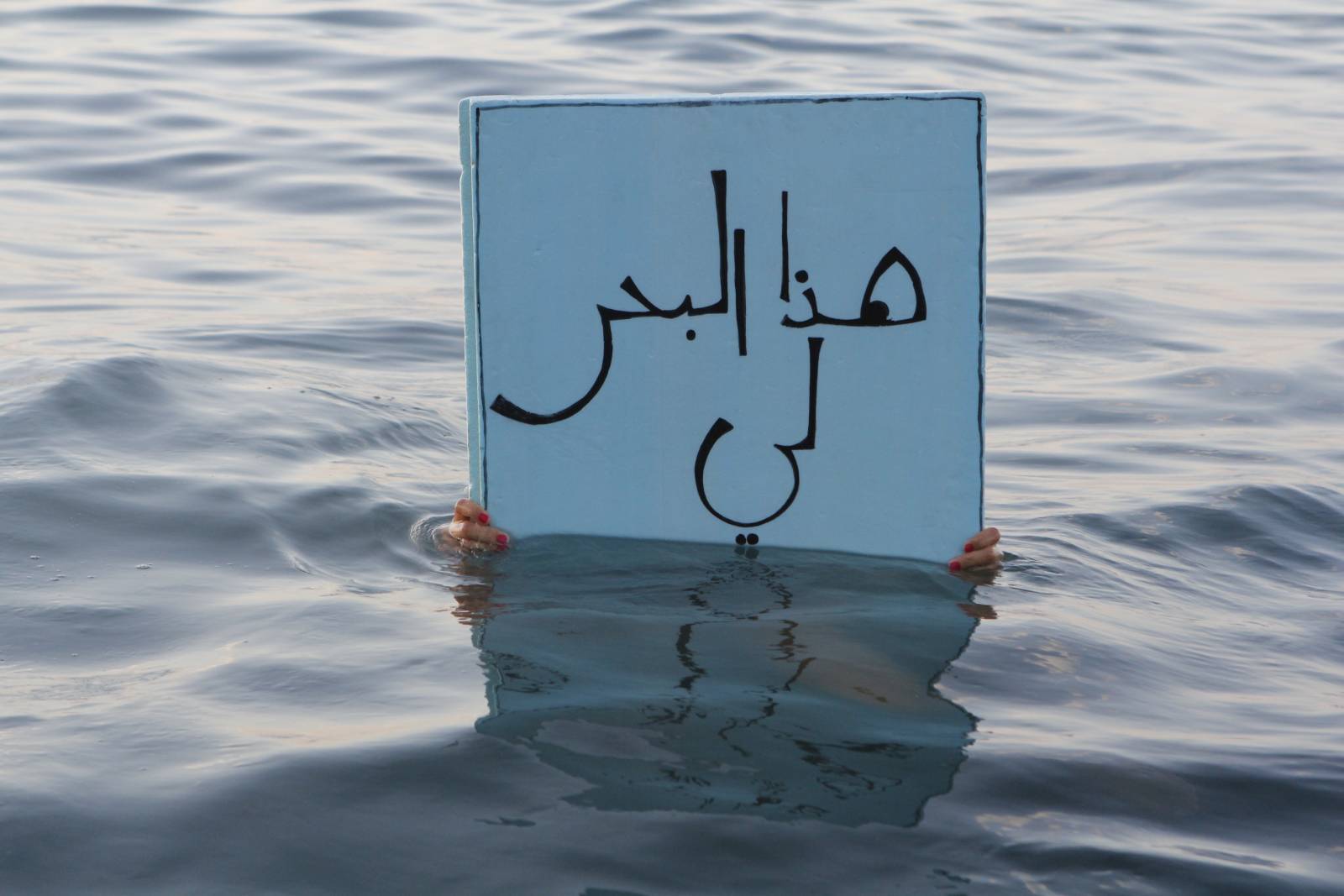

The room is divided into two separate parts: stage and audience. In the room we have people doing and people watching the doing. That’s the gap.

We face that gap from both sides. You open your mouth to speak—!!—to reach out over the chasm. I reach to meet you.

Excerpted from a first draft of Theater for Beginners