Susan Leigh Foster

Susan Leigh Foster, a choreographer, dancer, and scholar, is distinguished professor in the department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at UCLA.

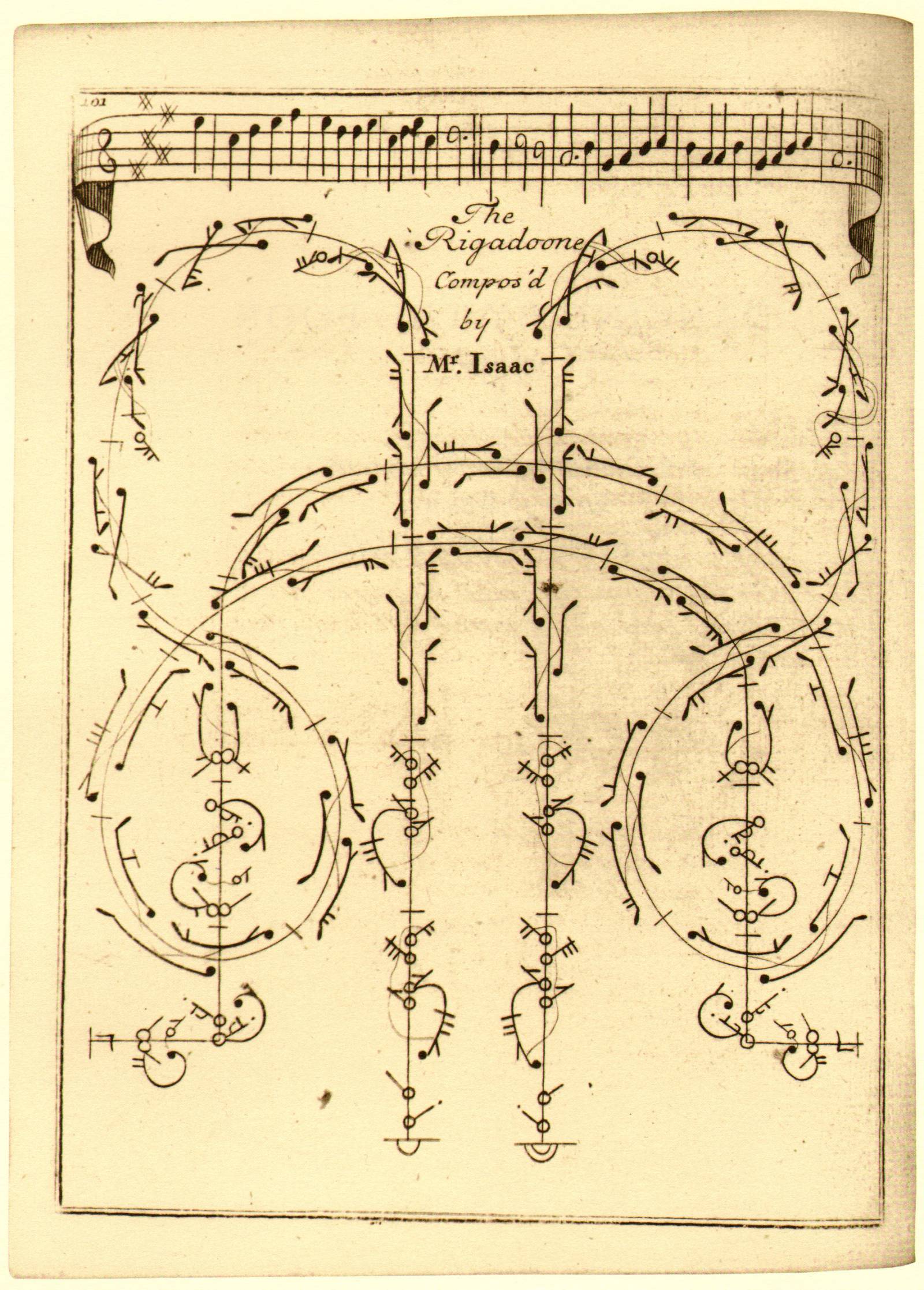

The term choreography was neologized in 1700 to name the act of notating dances on paper using abstract symbols. Invented by Pierre Beauchamps, Louis XIV’s dancing master, and put into print by Raoul Auger Feuillet, choreographies were notated scores of dances, and choreographers were the people who could read and write the notation. Establishing an innovative relationship among the body, space, and printed symbol, Feuillet’s system posited a small number of essential motions from which all dancing was composed. The system then integrated these elements into a single planimetric representation of the dancing body that highlighted its directionality, the path it took through space, and the motions of the feet and legs.

The notation regularized all dancing by assimilating any and all motions into a single system of principles, and it also taught dancers to maintain a single directional orientation as they moved through space by cultivating a bird’s-eye view of their own path. Both the principles underlying all movement and the abstract horizontal plane on which dancing occurred worked to create a specific conceptualization of the body’s relationship to space. Each individual body consisted of a centrality that extended itself outward into a neutral and unmarked space performing universal laws of physical motion.

By the mid-eighteenth century choreography as a form of notating dance had fallen out of use, and over the course of the nineteenth century the term was rarely invoked. When it was used, it referred indiscriminately to the acts of making, performing, and learning dance. It returned with a new urgency and immediacy at the beginning of the twentieth century in response to the radical approaches to dance-making associated with the burgeoning genre known as modern dance.

The term choreography began to be used to specify the unique process through which an artist not only arranged and invented movement but also melded motion and emotion to produce a danced statement of universal significance. This use of the term to name the creative act of formulating new movement to express a personal but also universal concern entailed new kinds of relationships between bodily training, creating, and performing dance. Whereas Feuillet notation located all movement along a universal horizontal plane, the new modern techniques foregrounded gravity as a universal within and against which the body articulated its dynamism. In the same way that Feuillet notation occluded the labor of moving from one place to the next, so this conception of gravity rendered equivalent the efforts of all bodies in all places. Students were trained in a variety of individually created techniques, each of which explored this relationship between body and gravity as a kind of drama of universal significance. Rather than progressing along a horizontal plane and tracking that progress in their awareness, students now learned to flesh out the volumetric body and to explore the tensile and sinuous connections among its parts.

Choreography became the unique process through which this momentum-filled body was tapped as a vehicle for expressing issues of both individual and universal concern. It no longer referenced a standard or shared repertoire of movements, as it had in Feuillet notation. Like the notation, however, it authorized the claim for unique ownership of a given dance. Both meanings of choreography secured the right to proclaim that a given dance was the product of individual invention and the property of that individual. The legal right to claim ownership, however, was established only in 1948 using an early twentieth-century form known as Labanotation to produce a score of a dance that could be copyrighted.

Since the 1960s new approaches to dance composition have prompted many artists to seek other terms for designating the process of creating a dance, including making, directing, and arranging. These artistic initiatives have expanded choreography’s meanings such that in recent years the term has begun to reference many ways of structuring movement and not necessarily the movement of human beings. Choreography can stipulate both the kinds of actions performed and their sequence or progression. Not exclusively authored by a single individual, choreography varies considerably in terms of how specific and detailed its plan of activity is. Sometimes designating minute aspects of movement and at other times sketching out the broad contours of action within which variation might occur, choreography constitutes a plan or score according to which movement unfolds. Thus buildings can choreograph space and people’s movement through them; cameras choreograph cinematic action; birds perform intricate choreographies; and combat in war is choreographed. Such uses of the term raise issues of agency and the structuring of power relations by calling into question how and where choreography is created and for what purposes.

For Further Reference

The Temperaments, 2012. Choreography by Alison D’Amato; videography and editing by Grace Fitzpatrick; movement invention and performance by Chris Domenick, Sam Herzlinger, Jonathan Matthews, David Pappaceno, Graham Watling, and Clay Woodruff.

“Move. Choreographing You: Art and Dance Since the 1960s.” Curated by Stephanie Rosenthal at the Hayward Gallery, London, October 2010–January 2011.

Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, 1913. Choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky.

Casebolt and Smith, O(h), 2010.

Harmony Bench, site/map/dance, 2011; rebuilt as Conn College Redux, 2014.

KineScribe, a 2013 iPad app that enables users to write, read, and edit scores in structured Labanotation, Motif, and Language of Dance.