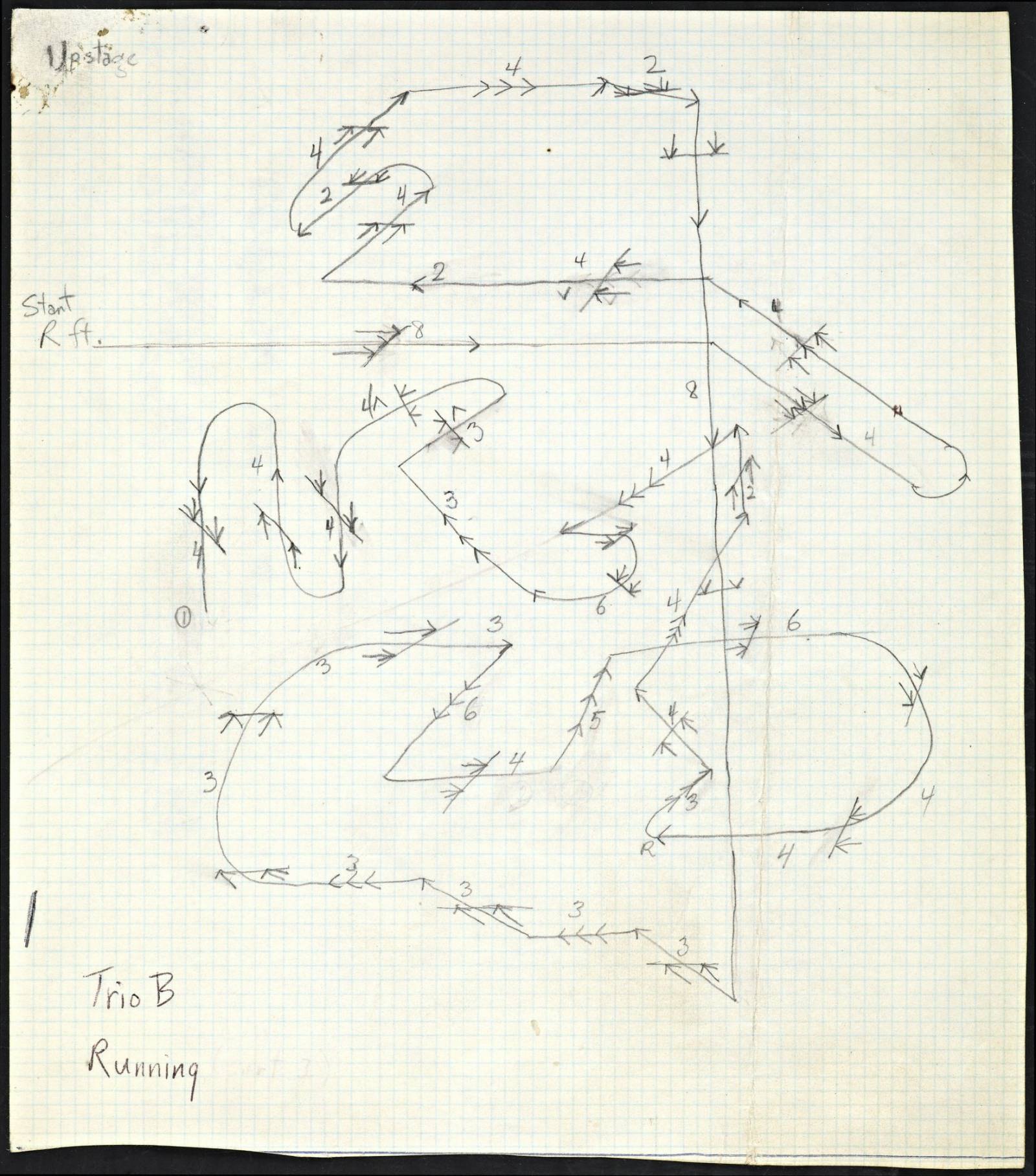

When I consider the most striking moments I have had as a spectator, the first that come to mind are those that affected not only my intellect but my body as well. Jan Lauwers’s staging of Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra (1992) hit me right in the retina. I watched Cleopatra die in her last monologue, highlighted with just one spotlight for a duration that felt endless; then there was dark, and I had this aftereffect in my eyes, a tough, disturbing green and red thing that was part of me and not part of what we all were supposed to see. She was dead, and I realized in the next moment that all of us spectators were touching our closed eyes reflexively, trying to get rid of this effect that we all know from looking directly at the sun. Then I realized that the fading of this afterburn was the equivalent of processing death, losing forever the last marks; it was the ex-presence of somebody who had just been there. Wow. This is what theater can do.

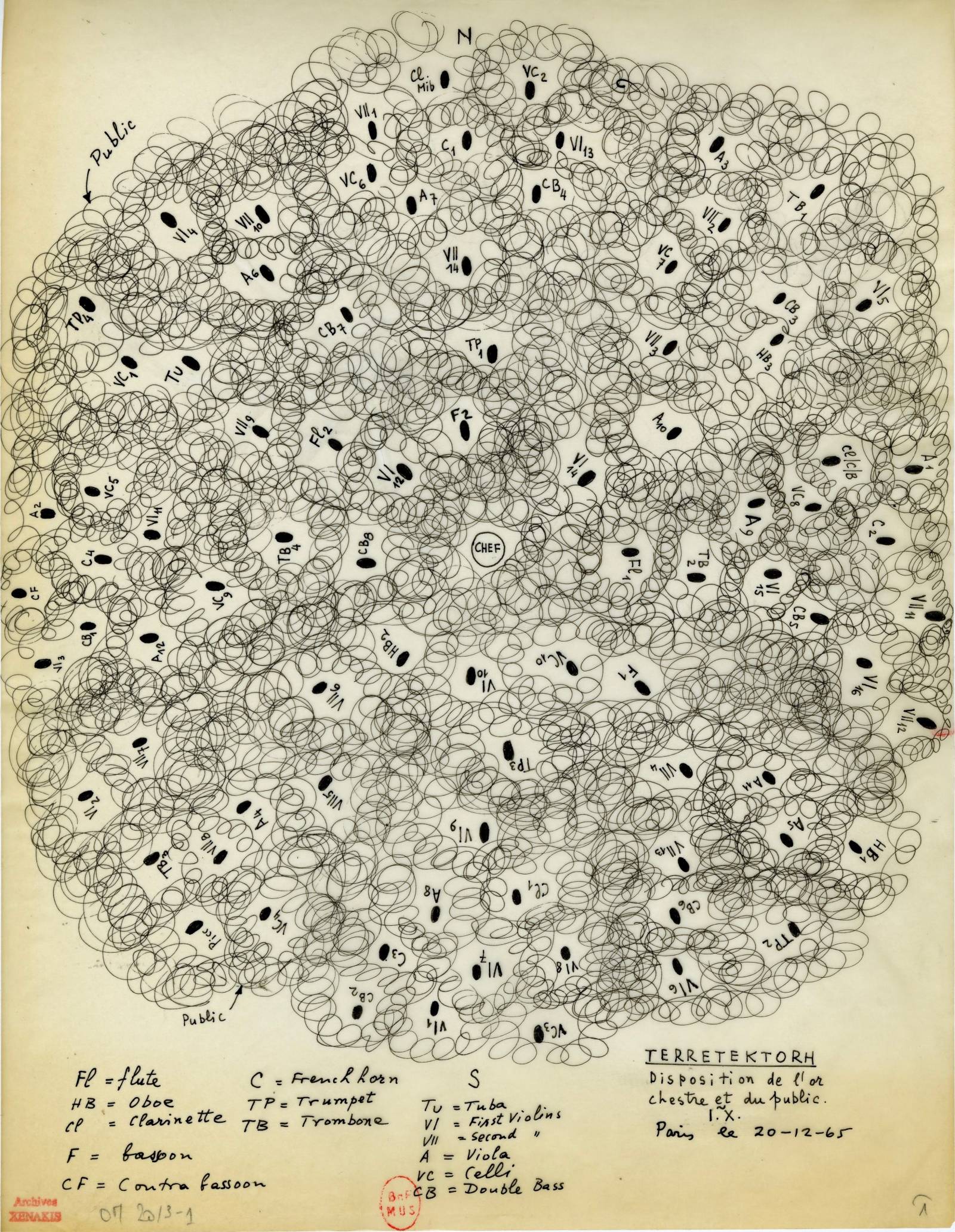

I had a comparable experience watching TV about the same time, in the ’90s, when a woman on a talk show claimed she could live on what she absorbs from sunlight. She said she had not eaten anything for years. She explained that we all could live like this and that this would be the sole chance for all of humanity. Great show. She was talking about the content of sunlight, not the studio light, but suddenly the TV screen went black, and the anchor asked, “Do you feel hungry now?” She said no, but what a mess. Maybe the few hundred in the studio felt an effect—for them the light priestess might have felt like my Lauwers Cleopatra—but on the TV screen it did not work. Ultimately, to be a spectator of theater starts from the point of sharing the same space, the same conditions of visibility.

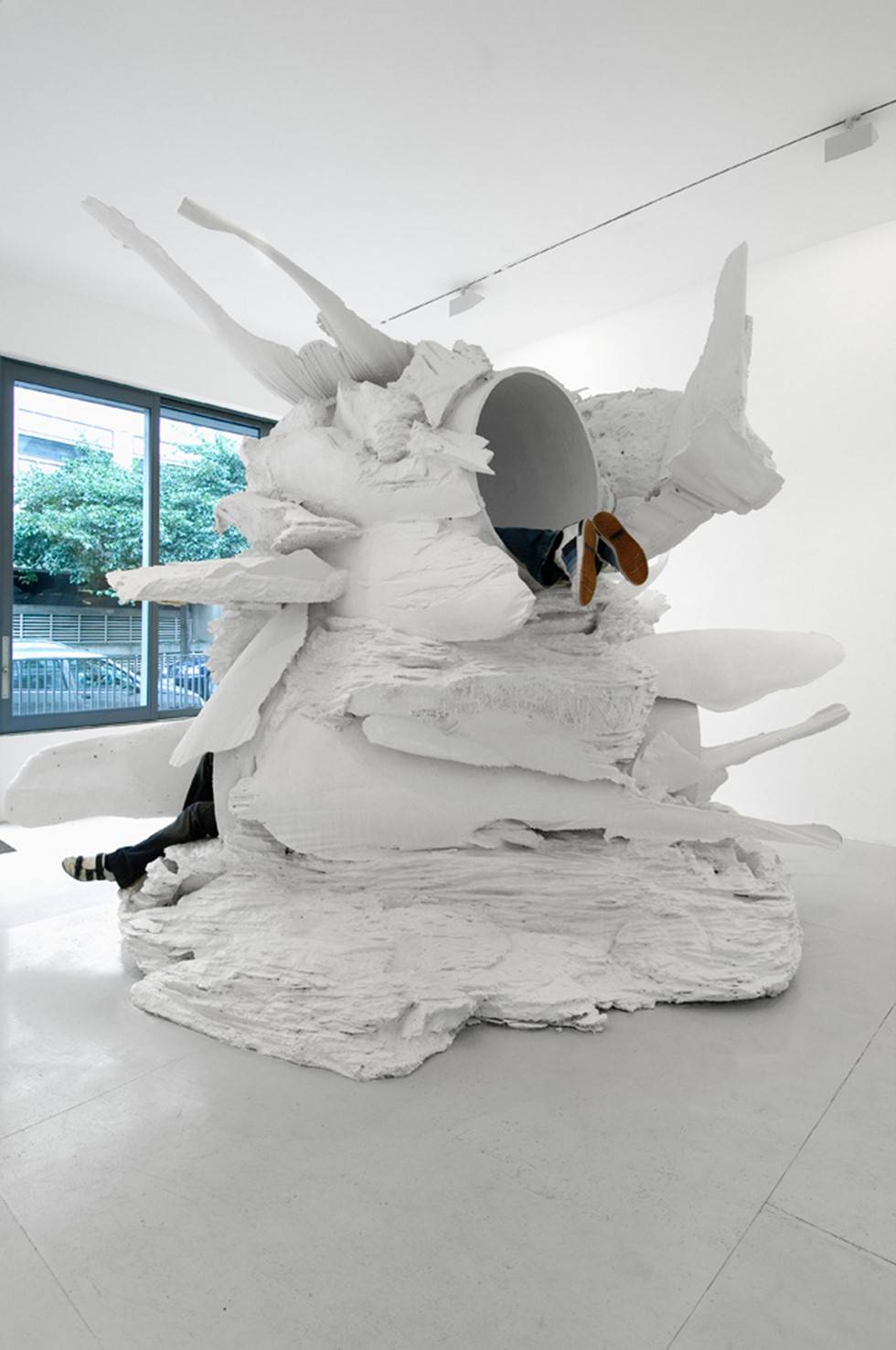

When we started to work together as Rimini Protokoll, a decade or so of exploring the consequences of Cleopatra’s death had passed, and we’d been sitting in the audience during that time. We’d observed with admiration how Robert Wilson, Jan Lauwers, the Wooster Group, and all those masters took conventional theater—as in, what I see is what someone else produced for me to consume—to the point of no return and then explored the realm beyond. Significance and the signifier, every dimension of meaning and reference emerging and vanishing, danced around us during that decade. We saw Queen Abramović flying over thousands of fresh flesh bones on a stage like a goddess and then coming down to stage in order to once more reenact her most important performances and reflect on her partnership with Ulay. We saw Ron Vawter doing his last performance with the ashes of Jack Smith on his face mixed into his makeup. But then we also started to watch people just doing their work far from anything they would call a stage. They would just perform their procedures and duty, and for us, they were performing a part on this stage where we are all merely players. So interesting because these everyday performers are not at all concerned with matters of perception. They had not seen Cleopatra and did not know about what Derrida had written, much less Lyotard or Barthes. Theater at the end of the ‘90s was the perfect place to dive into an endless vicious circle of philosophical questions about subjectivity, but any question about what the hell the performance was about, at least in Europe, was answered by the assertion that we did not sufficiently trust our own perceptions during the performance. Whoever asked about the point of a performance felt like an idiot in those days because the systems of references, the complex intersections of symbols turned into performatives, of performative acts turned into fields of open reading, etc., led to the bare counterquestion, “What did you actually perceive and what do you think about it?” And you just went, like, “I don’t want to play the child in your Lacanian kindergarten. I am really interested in everything beyond the shield of your jungle of theory. Just please share what the heck you guys from the other side of the fourth wall are thinking about!”

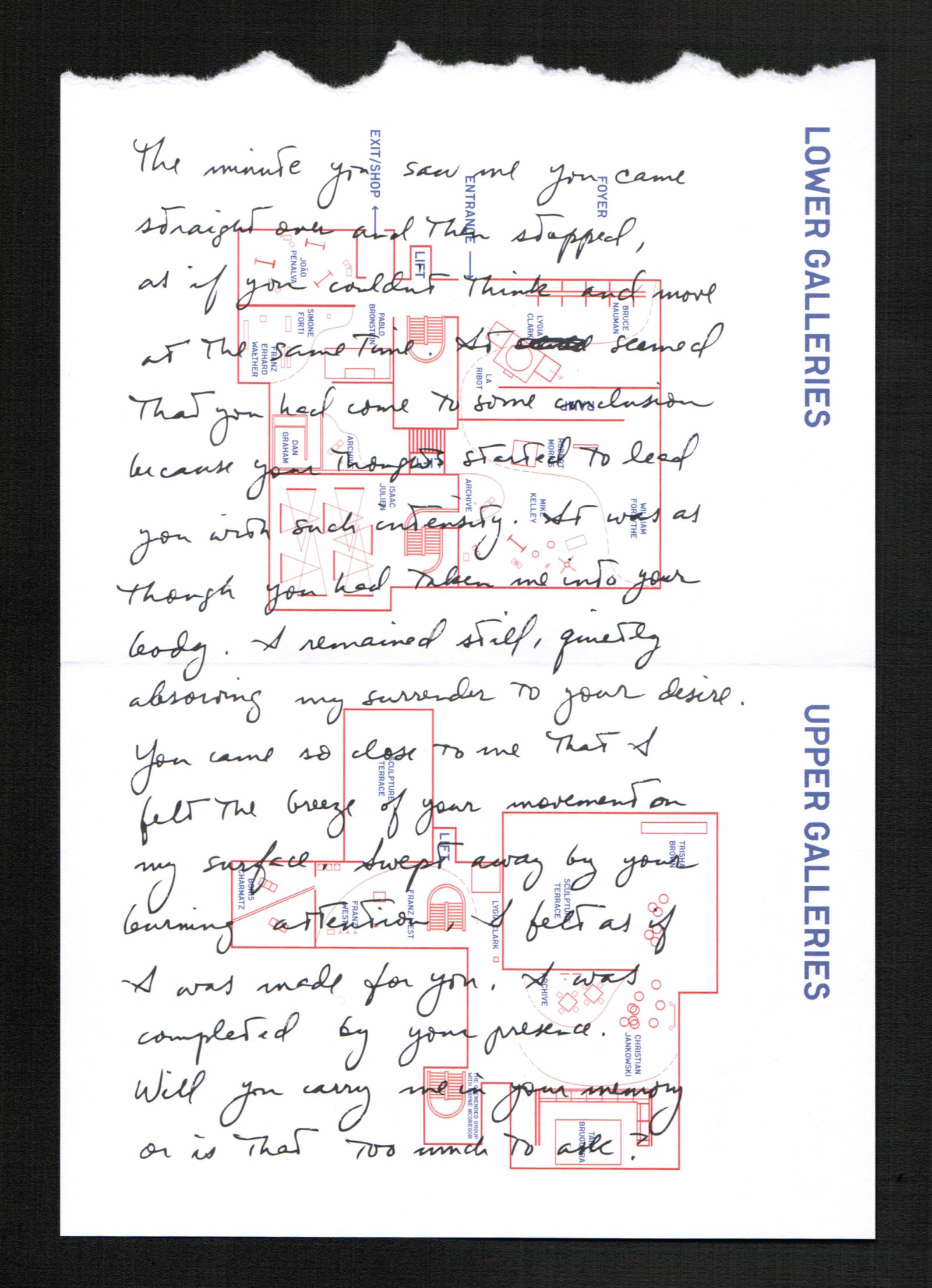

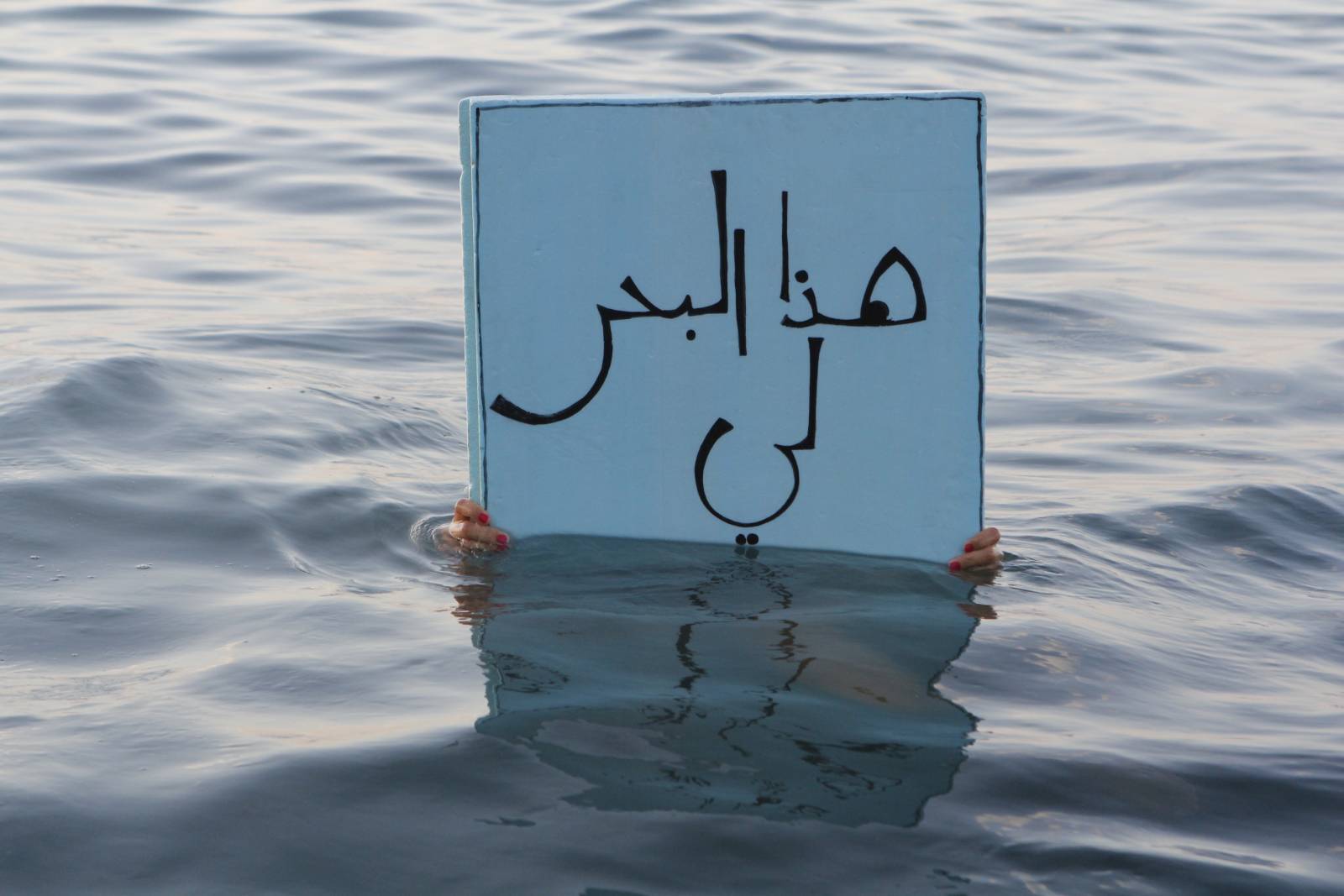

We spectators, a couple of years later, know in advance that it is our individual experience that counts. We buy a ticket to this guided tour to whatever; if it is provided by performance artists or taking place in some kind of arty surrounding, we download that mental or Google app that assists us in locating ourselves appropriately. We are in a state of welcoming everything on the streets, in the parliament, on TV, in our beds, as interesting performances, no? And the question is whether we think for ourselves about what we experience or if there is already some blog post that might suggest a reading. But as a countermovement in us toward the chic death of all signs on our retina, the ashes of postperformativity discourses that would shift every meaning to the complex of the reader and his or her perception and reflection, theater has become a source of emphasis, capturing the moment of subjective interest wanting to understand through participation. We don’t need the antinarrative strategies of deconstruction to overcome narratives; we are faster than playwrights can think. We know we’re on that highway to hell. We understand that respect, family, partnership, belief, democracy, peace, sustainability depend on our own small steps within our own contexts. Theater is no more the resource of catharsis; we got the message. Theater is just the chance to make experiences that we don’t know, in detail; a platform for exploring fields I have not visited, thoughts I have not thought, people I otherwise would not have listened to. It has turned into a field of experience in which I explore what happens to my retina and my whole perceptual apparatus wherever I am. It turns me into somebody who can observe what happens and say what I think about it. I am open to what happens in me while I observe that you want to show me something; my interest is all yours, while I can’t forget that between me and you is just a membrane that allows you to penetrate me with whatever specter (ghost) you perform.