Nine-year-old Yaoundé Mulamba Nkita was in French class when he heard his classroom bell sound. The teacher cried, “On the floor, on the floor!” It was 1998 in Kisangani, in what was then Zaire and is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A few days later Yaoundé was with Laurent Désiré Kabila on the way to Rwanda, where he was to be trained as a soldier. Five years later, after dozens of murders and war crimes, Yaoundé was finally able to escape his role as a child soldier.

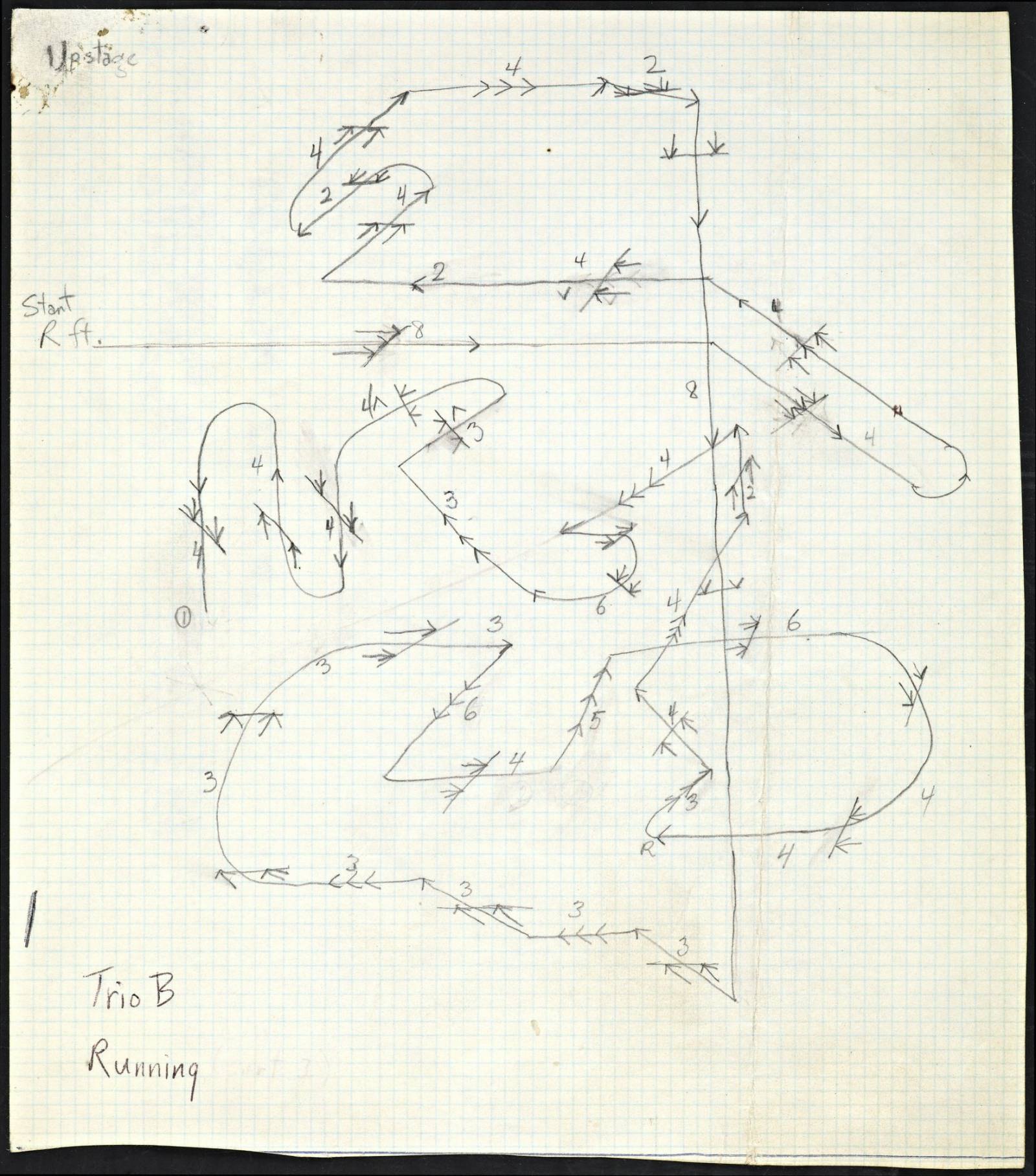

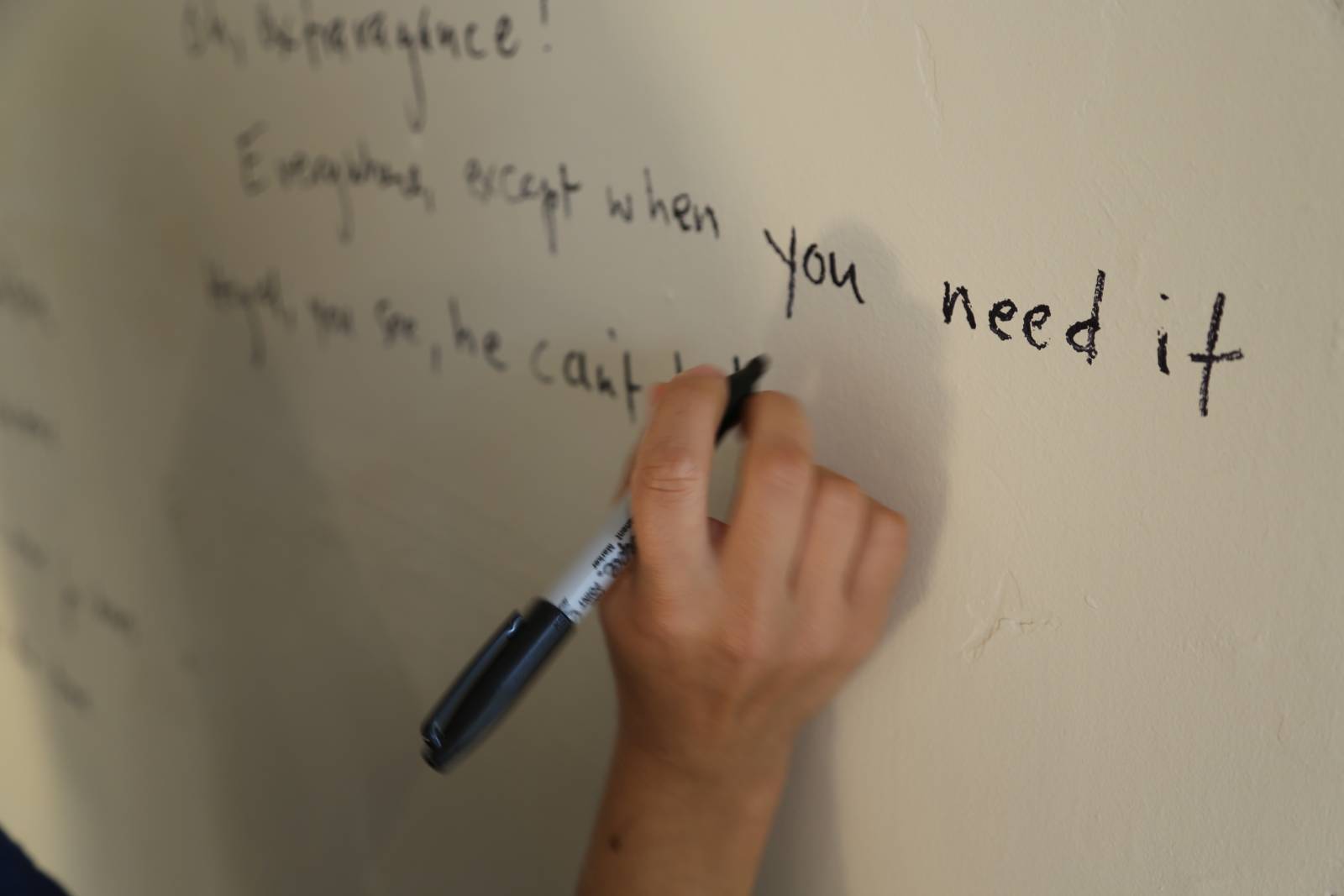

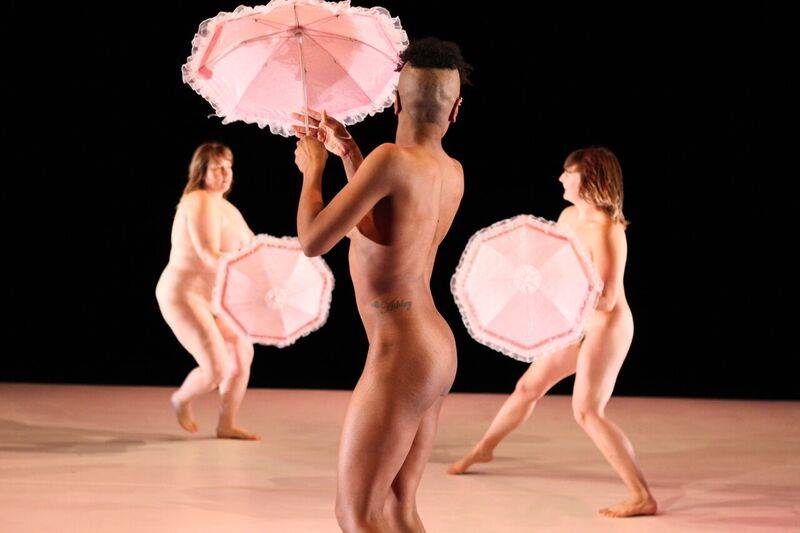

For Situation Rooms our stage designer, Dominic Huber, reconstructed a corner of Yaoundé’s Congolese classroom. Ten years after Kinshasa’s capture, we rehearsed with Yaoundé the reenactment of his recruitment. With a prop Kalashnikov rifle in one hand and an iPad mini in the other, Yaoundé went once again to the floor, raised a flag, and opened a door, as he had done back then. From sentence to sentence, his improvised text unintentionally alternated from past tense to present and back again; it was as if he was falling through a hole in time into the past and from there back again into the present.

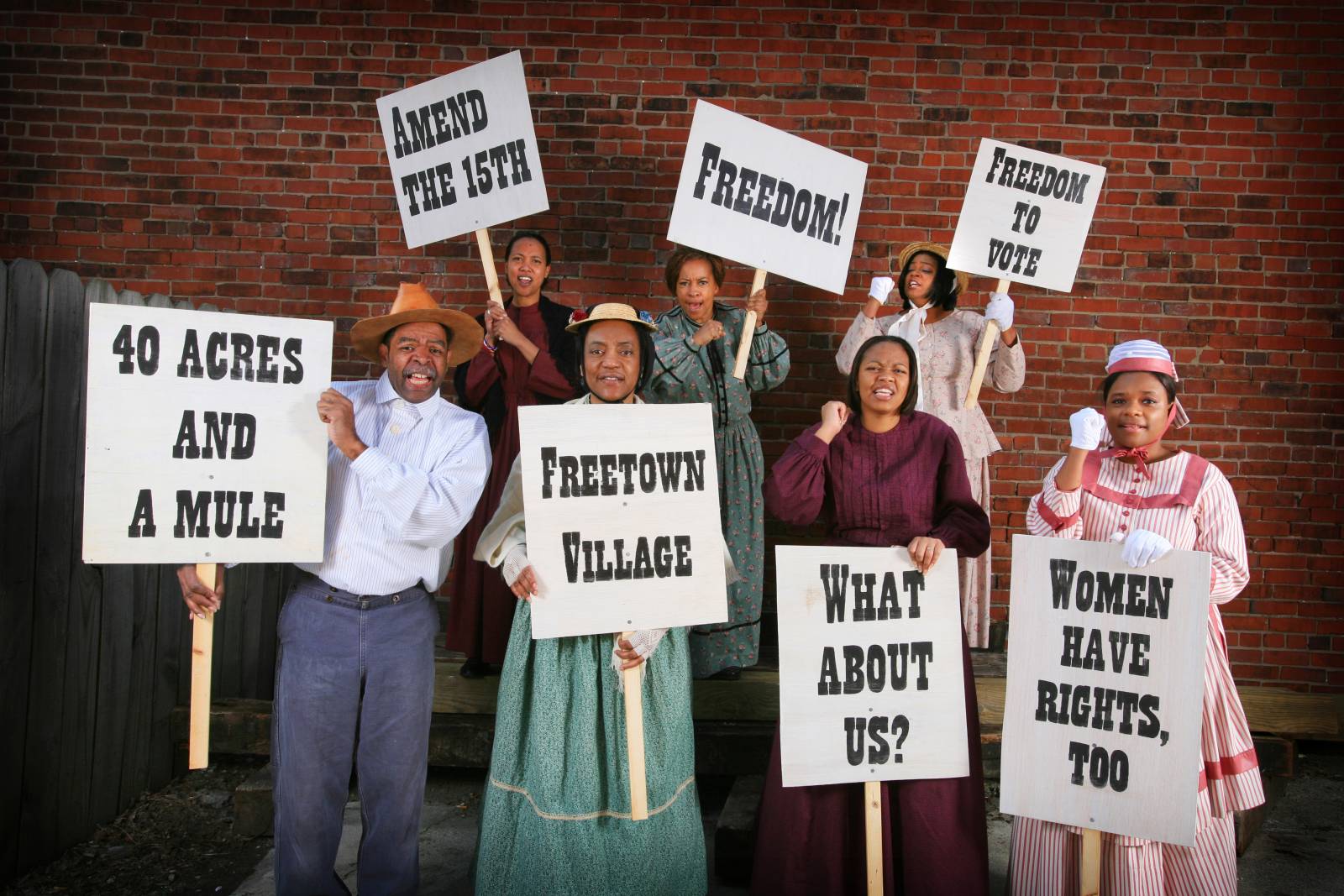

Under the rubric of reenactment, thousands of amateur historians collect and reenact medieval battles. In the process they pay great attention to the minutia of costumes and props. Each of these signifiers emphasizes the pastness of the event. In this way, such reenactments often appear peculiarly abstracted (and “off”) and somehow useless.

Today, parallel to such historical reenactments, artistic projects often go far beyond the scope of historical reconstruction, especially when they move the live enactment of the past and its recontextualization into the foreground. In lieu of experiences out of history books, such projects often refer to subjective narratives and memories of history’s minor characters. They recall events whose aftershocks are felt to this day.

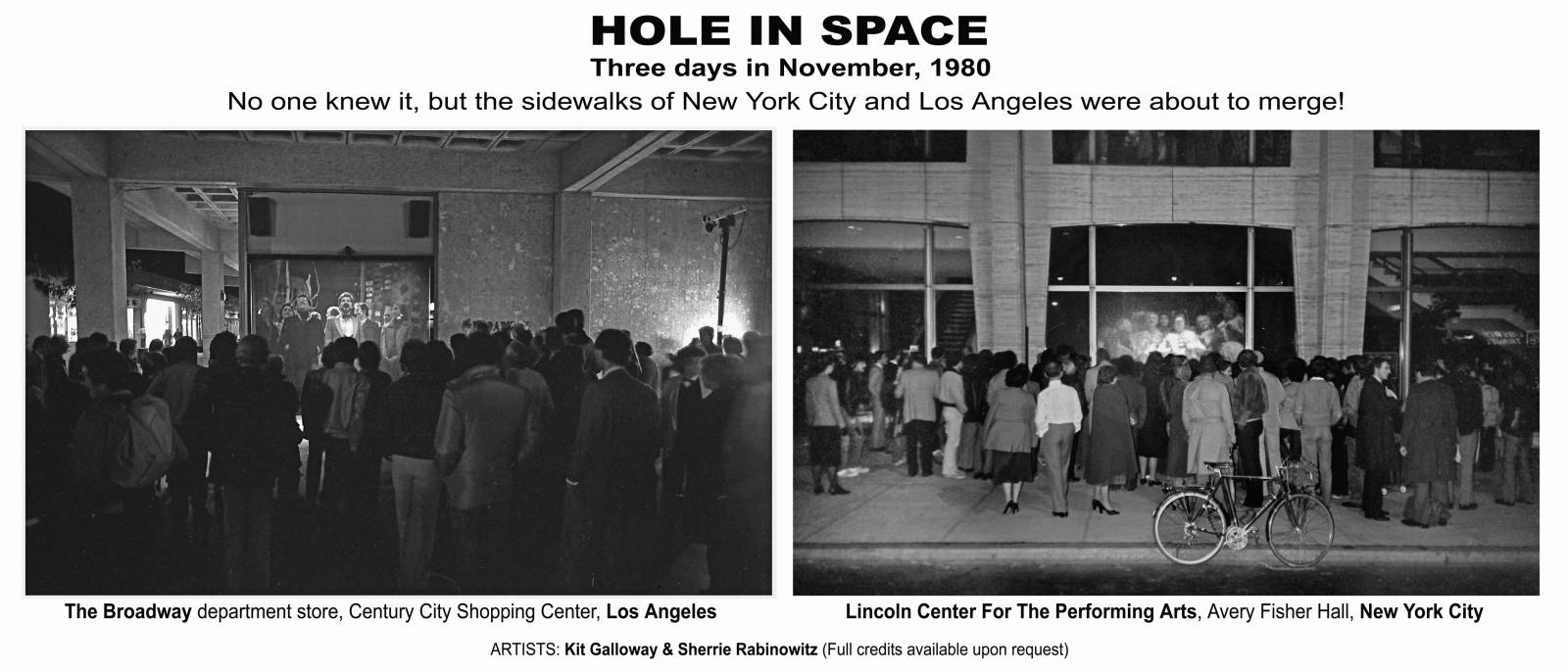

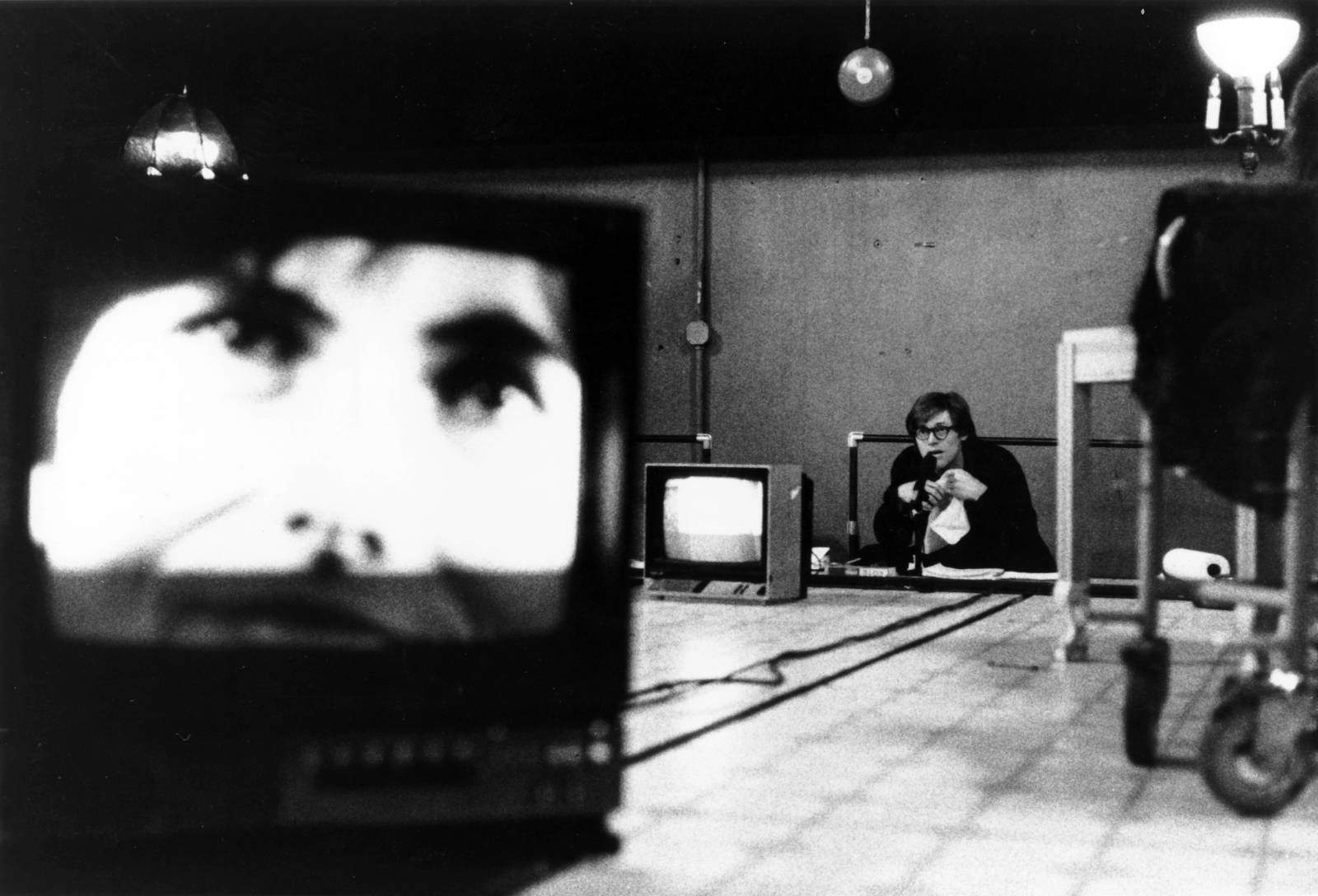

In 2009, when Milo Rau worked with Romanian actors to restage the videotapes of the trials against the Ceaușescus, the performance in Bucharest was legally prohibited because the Ceaușescus’ descendants were against the reenactment; a Romanian court decided that the family still had the rights to these texts. In this case the country had apparently not yet come to terms with its history. The distance between history and its reenactment was too small, and the debate over public and private access to such a transcript was still unresolved.

In our Situation Rooms, Yaoundé reenacted his own role. His task entailed reconstructing the situation of back then once more. He was not filmed in the process; instead he himself filmed from his perspective the floor: the flag, the doorknob, and his hand, how it opened the door. It is quite possible that, with each rehearsal, he moved himself one step further from a factually accurate account. Historical fidelity was not the point.

How precisely did Jeremy Deller reconstruct his reenactment of the miner’s strike in South Yorkshire, The Battle of Orgreave (2001)? He let the conflict be reenacted by former participants as well as historical reenactors. In doing so, the point was less to depict what happened in 1984 than it was to explore what happens with people in 2001 when they reenact the Thatcher era. Many former miners chose to play police officers this time. And some police officers joined in with the reenactment at the demonstration site.

With each repetition, Yaoundé made his past his own. And that is likely the difference between a historical reconstruction, which tries to remake the past—and forgets that the observer and the participant cannot themselves travel to that time—and a reenactment, which constructs the past in the present, invents the past in the present.

In 1927, when Sergey Eisenstein shot thousands of extras for the scene of the storming of the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg in his feature film October, he created the image that the majority of those born after the event have in their heads as the beginning of the October Revolution. The image of the historical event overlays reality. And what else can reality be than one of many memories of the moment? Each photo can provide only one of hundreds of possible perspectives on that which is represented. The monumentality of Eisenstein’s film monopolized the past.

My colleagues from Rimini Protokoll and I are theater makers. The cause for my goosebumps when viewing Yaoundé’s reenactment lies not in the past but rather in the reenactment.

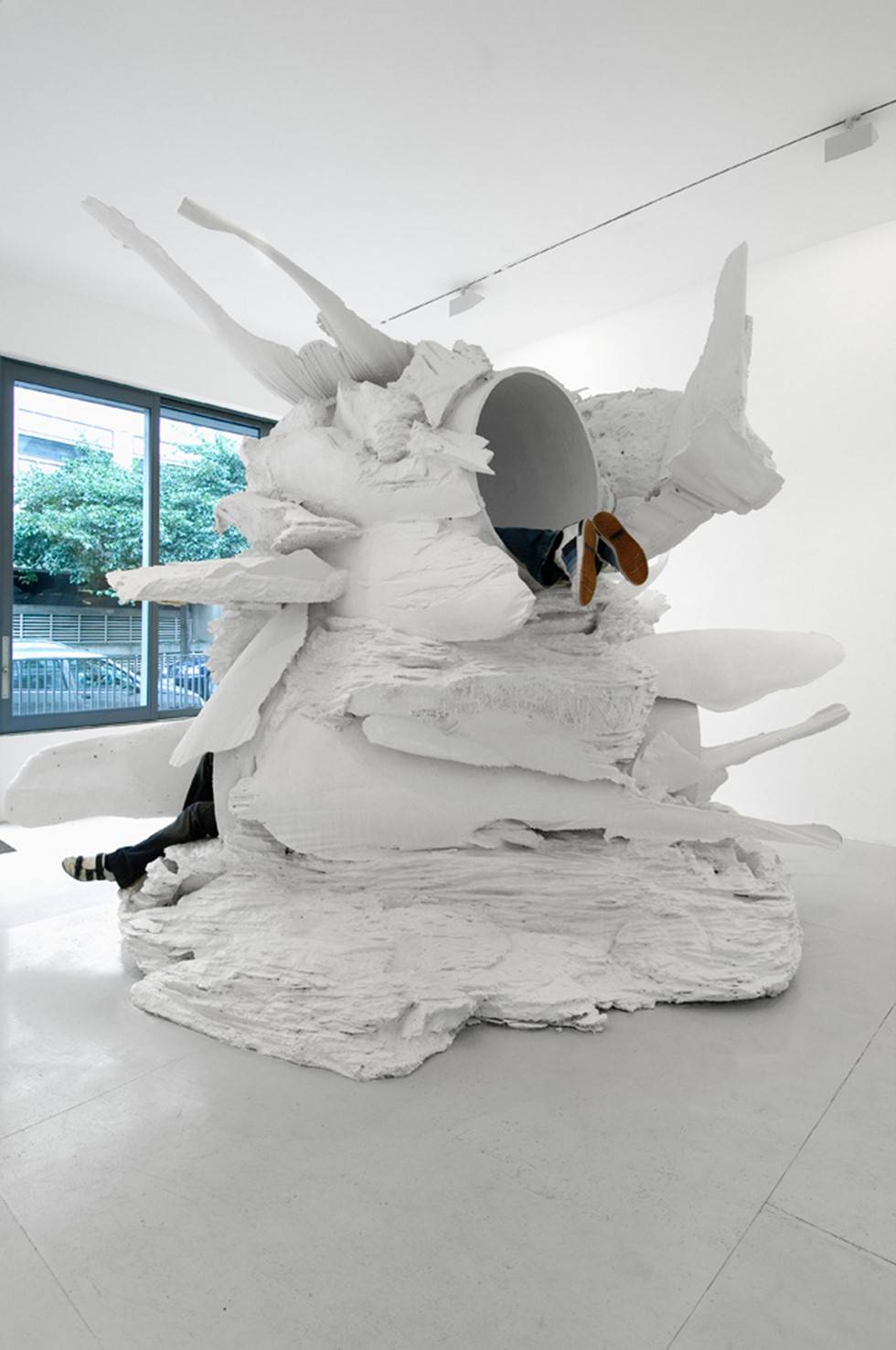

When Yaoundé tried to press down the door handle at the shoot of Situation Rooms in March 2013 in his reconstructed classroom with the prop Kalashnikov, there stood, in the adjacent reconstructed Mexican graveyard film set, Alberto, who, as the administrator of Juarez’s cartel, was responsible for the transfer of cocaine into the United States; he stood in front of the graves of the people for whose deaths he is accountable. The graves were made out of papier-mâché, so there were no bodies, but the memory thereof was written so clearly across Alberto’s face that one briefly hoped he would regret his past. But this reenactment was no therapy session, no Familienaufstellung. The goal was not to heal. On the contrary: Alberto once again enacted his total indifference toward his victims. His deeds were still so recent that he could appear only under a false name.

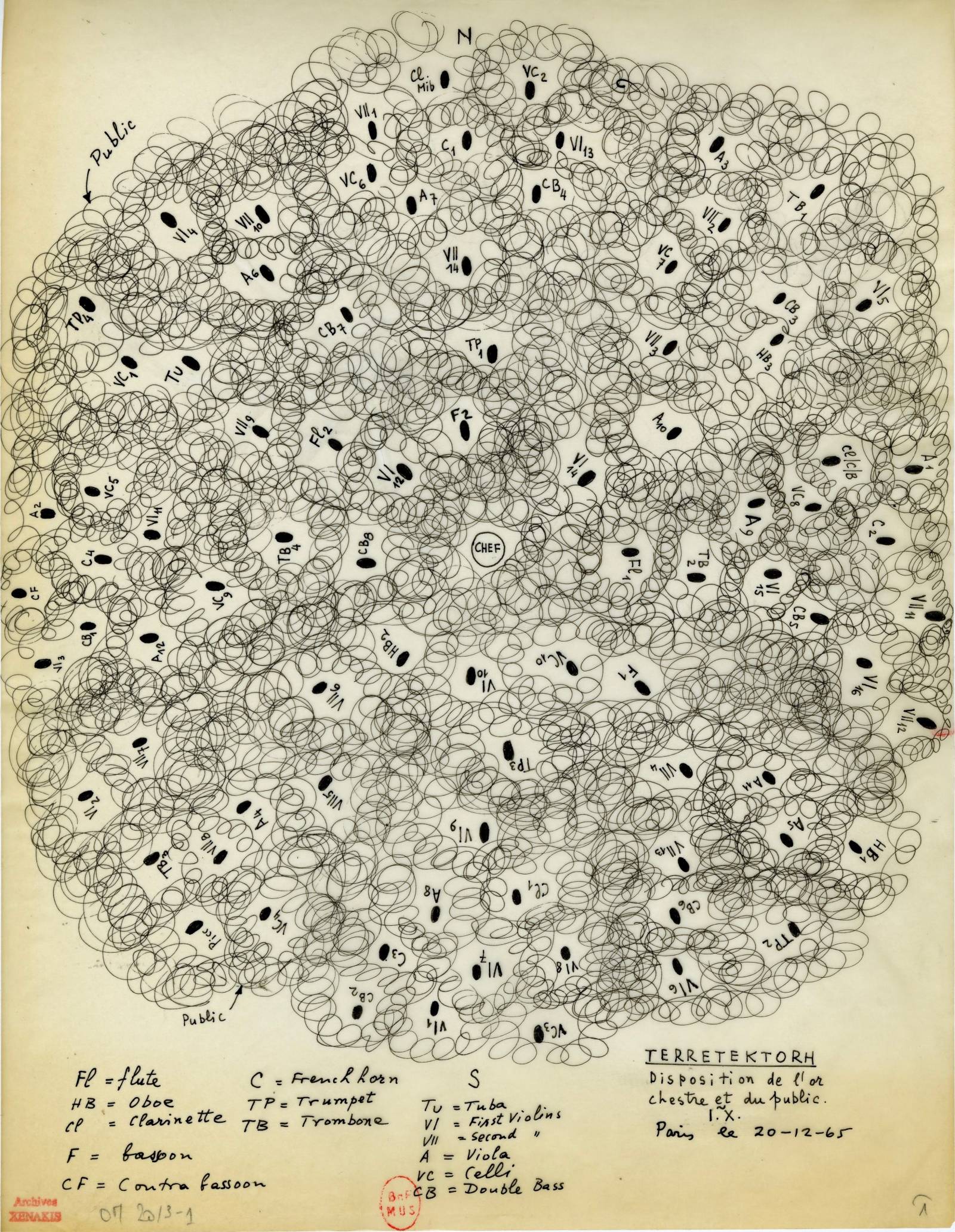

Behind the next film set wall was a weapons manager from Switzerland, a Bundestag delegate of the left, the former chief of protocol of the Munich Security Conference, and a doctor from Sierra Leone, who performed moments from their lives such that for a moment they became alive or comprehensible, not as a single fate but rather as one of twenty puzzle pieces in a model of the global arms trade.

With reenactments, viewers, players, users, or concerned persons themselves climb once again into a stranger’s skin or their own. The result is, in the best case, farther from the past than from the present. It is an anticipatory simulation game that prepares us for the arrival of the future.

Half a year after the shoot with Yaoundé, I watch a viewer who—with iPad mini in hand—hunches up on the floor like Yaoundé. She follows the subjective tracking shot on the screen. She looks at the iPad mini, crouches down in a Congolese classroom that stands in a theater in Bochum, spins toward the door, and aims with the screen, maybe like Yaoundé had aimed with a real Kalashnikov in Congo. She embodies Yaoundé. Maybe. I do not know what is going on inside her, but I suddenly think that this contemporary form of theater is closer to the classical dramatic theory of Aristotle than any play on the stage could be: identification and catharsis. Not only in spirit but also in the bodily sense.

Translated from the German by Megan Hoetger and Aleksandr Rossman.