Claudia La Rocco

Claudia La Rocco, a poet, critic, and performer, is editor-in-chief of Open Space, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s digital publication and community platform.

Ephemerality. 1822 Carlyle early letters. That's about it.

Ephemera is Greek

The above is what my mother sent me (thank you, OED). Origins et al. I didn’t look further. I’m not sure what I would be looking for.

As stated in my entry for duration, this is the word I chose. I had a bunch of reasons, none of which I can remember, and in living with this word for the past little while, it has occurred to me that I might have chosen it simply because it irritates the hell out of me. I hate, hate, hate how it’s bandied about within live art (I do it too), all breathy and churchy. Either bemoaning or celebrating, one or the other of those tedious poles.

First of all, it’s amusing, in the scheme of things, that creatures with our life spans would feel qualified to describe anything as lasting for a very short time. Typical human presumption.

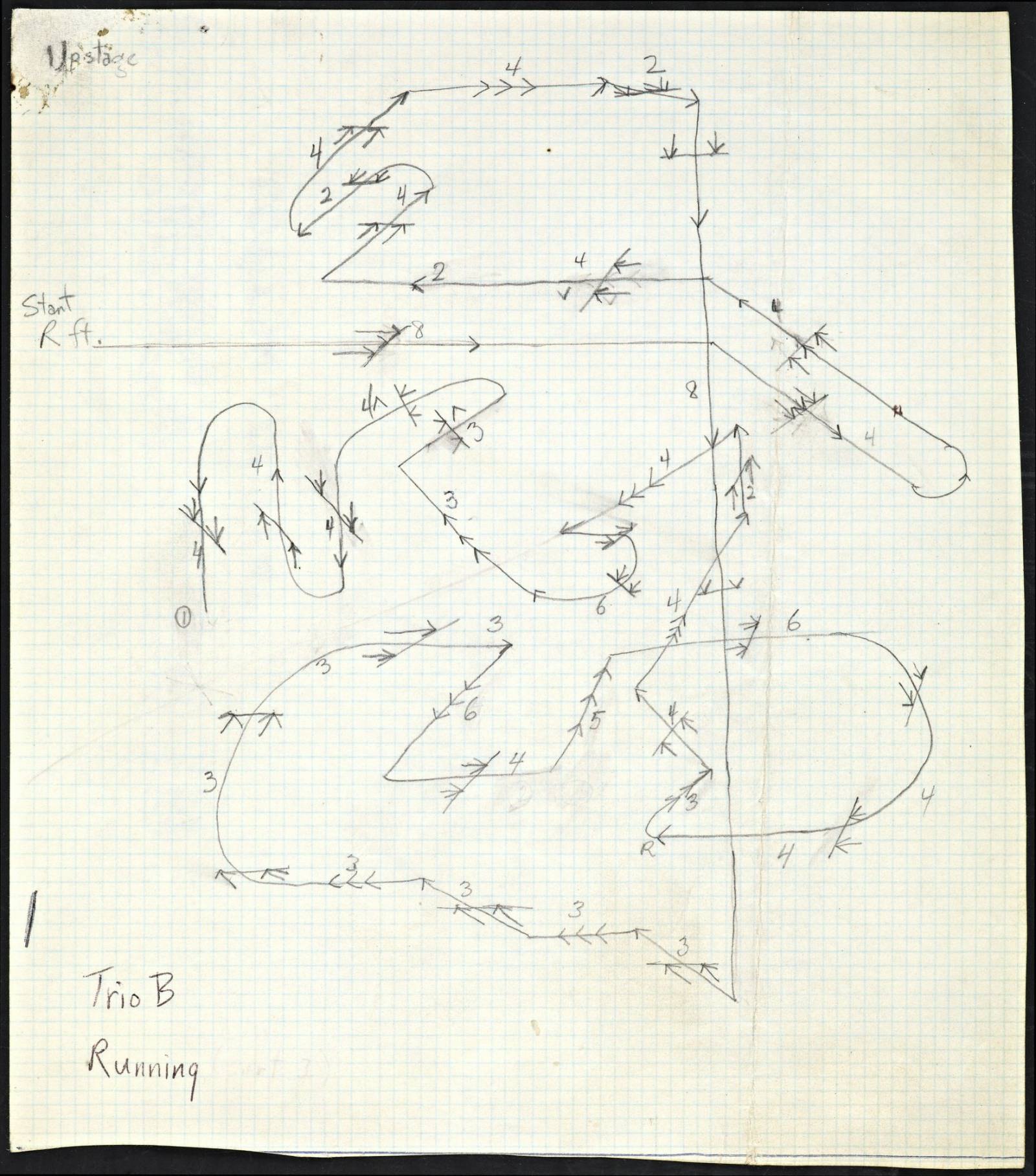

Second, I actually think it isn’t really true. Performance lasts a really long time. Through memory, through repetition, through tradition, through hand-me-down, through the good old mobile body archive. Does anything outlast nostalgia?

But this is meant to be a definition not a rant. So. What can I tell you?

[Period of time spent staring blankly at computer.]

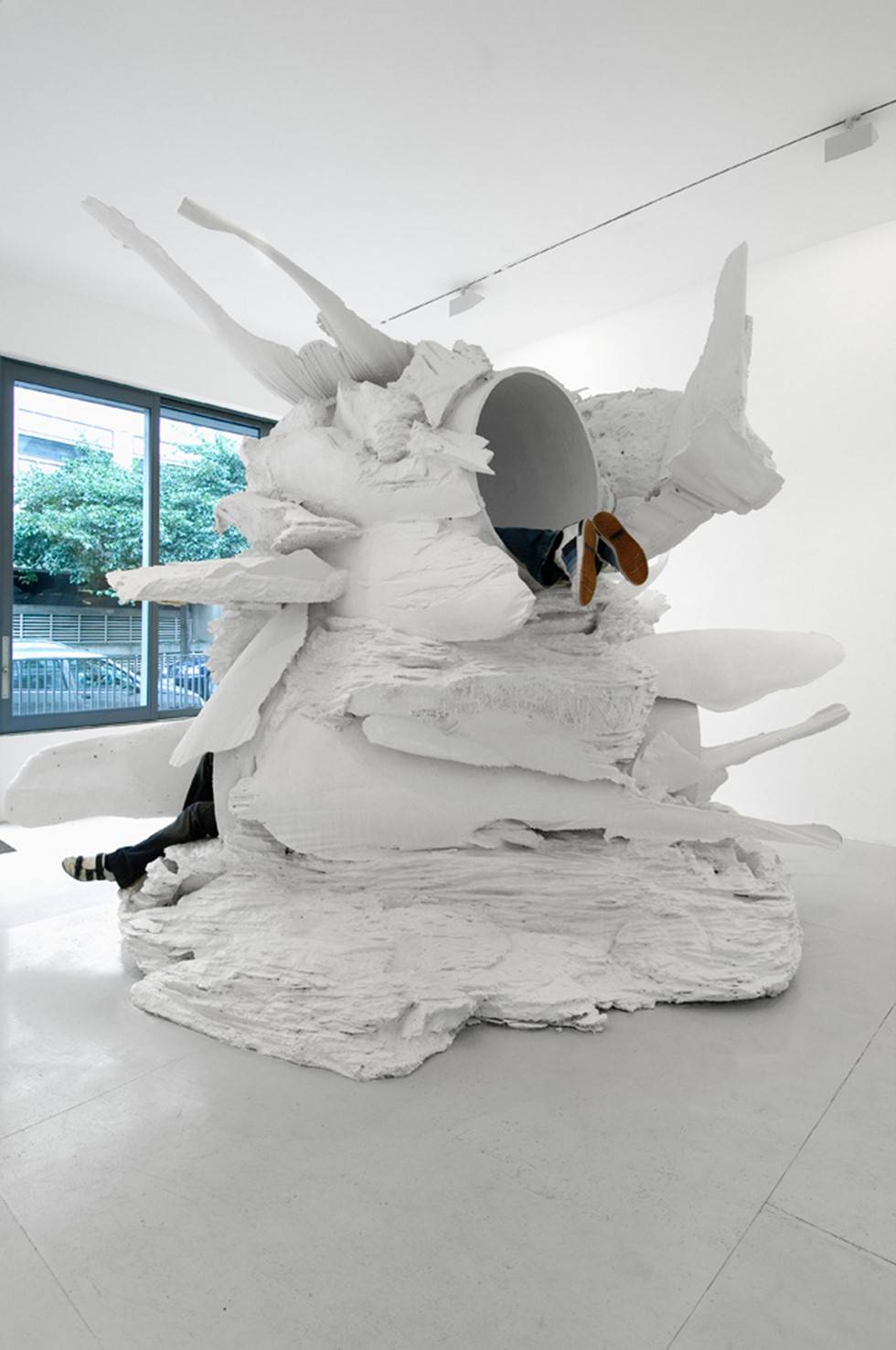

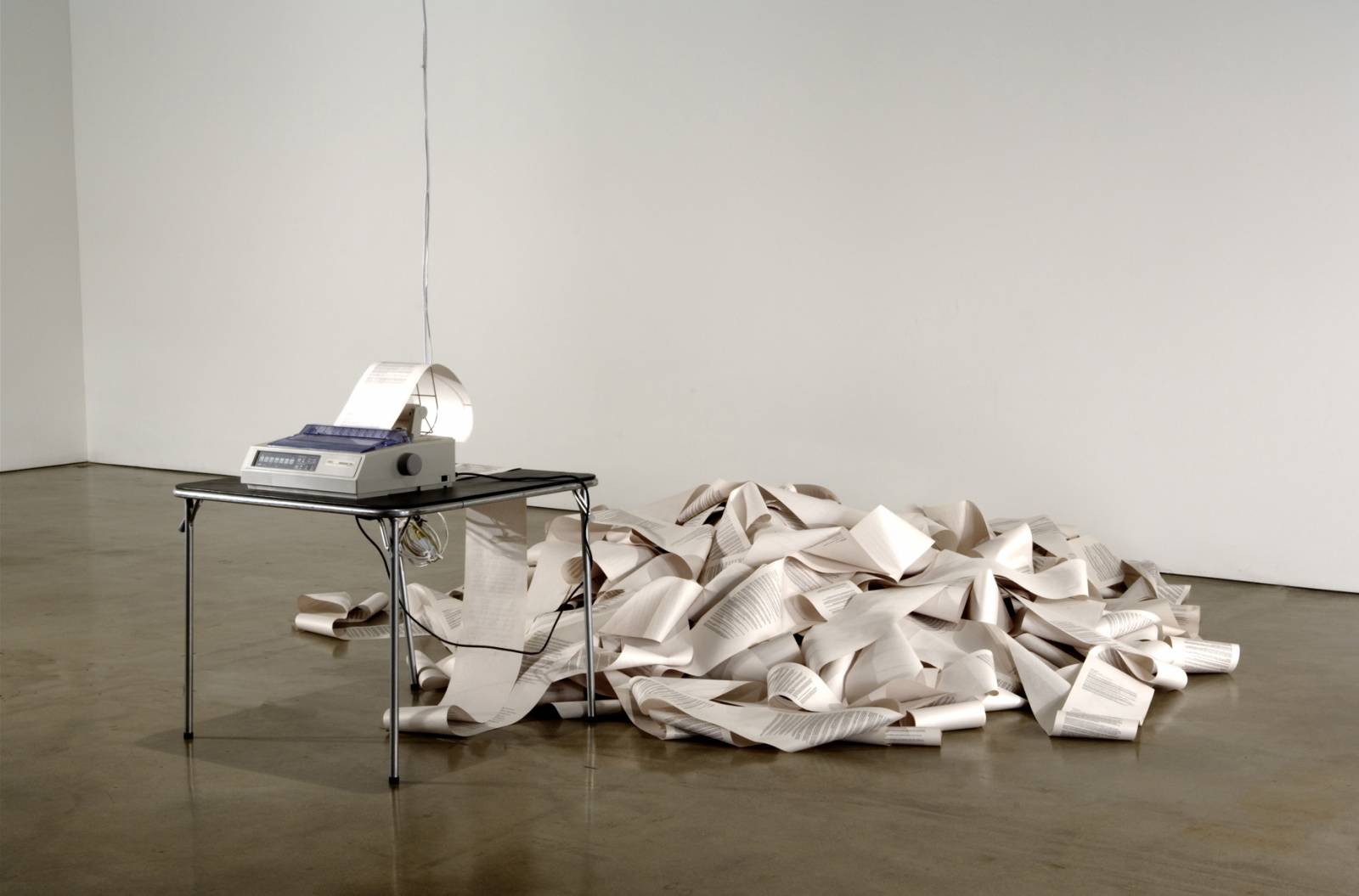

All that’s coming to mind is death and the economy. (Sorry.) And by that I mean the business of collecting. The haves and the have-nots: those with something to sell, those without. That’s both a cynical and a simplistic way to put it, but it’s hard to talk about ephemerality without thinking of what’s left over once the thing itself goes—and how there was no economy for performance until the thing the economy decided it needed was performance, performativity (god help the poor bastard who got that word), the experience if you will. And then everyone had something to sell, except of course for those unestablished unfortunates left holding their objects, themselves the products of ephemerality, because really the only true materials are space and time. The rest is window dressing.

Not that there’s an economy now. Just that, well, everyone’s hustling. Jazz hands!

It is true, of course, that we have no way of knowing if iconic events like Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring were any good at all. Is this the same as saying the ballet was ephemeral?

And back to that whole life span thing—we swim in the fleeting, do we not? Pick up yesterday’s masterpiece novel, and today it doesn’t suit. What went away? What entered? Take pictures of the family vacation to the Grand Canyon. Good luck getting anybody to be interested in your photos. (That of course gets us into the whole other distasteful terrain of performance documentation. I dunno about you, but let’s not.)

So if nothing lasts, what does it even mean to have a word designated to describe a category of things that really, really don’t last? What are we really talking about here? I have not very many allotted words left in which to attempt an answer. The clock is, as it were, ticking.

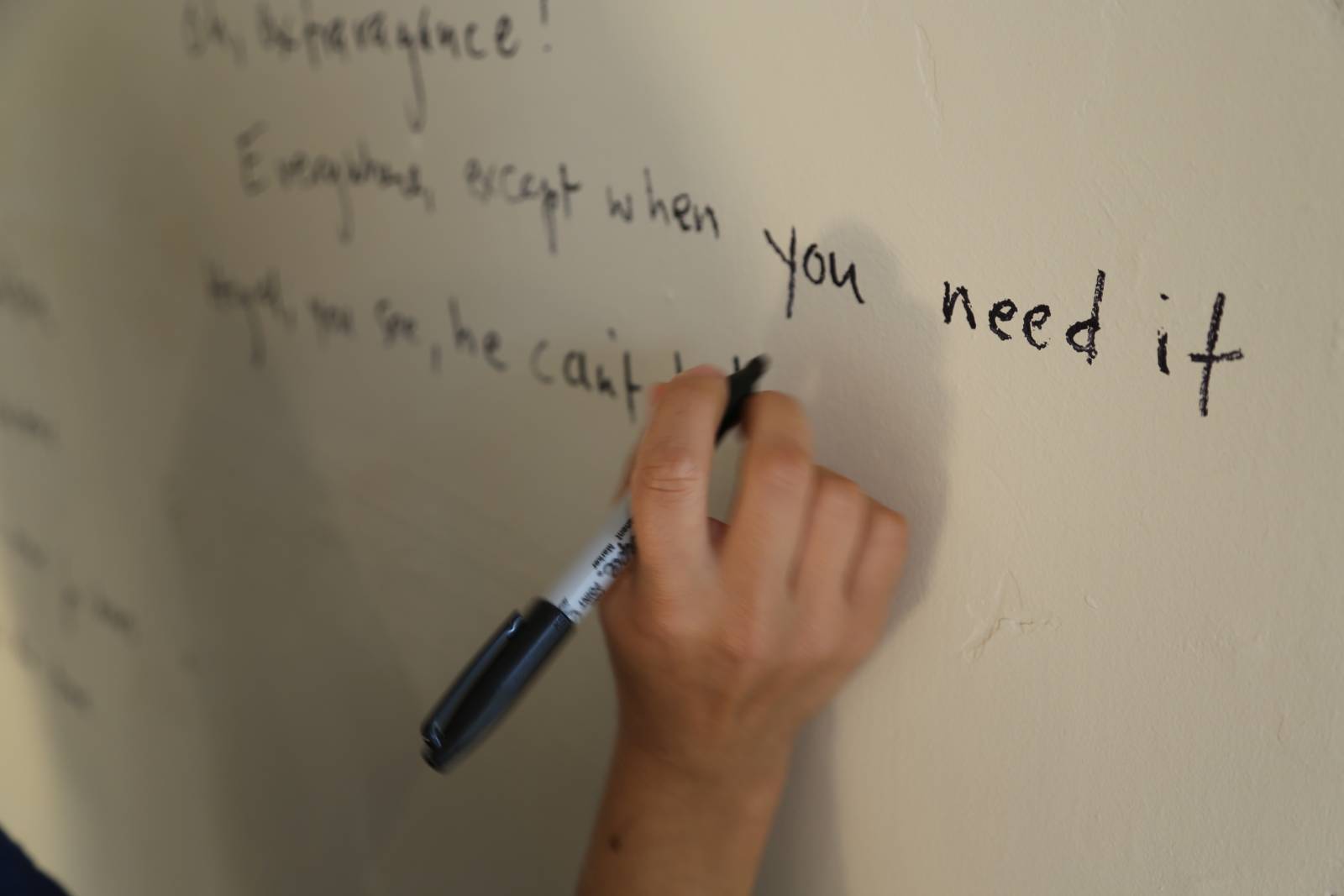

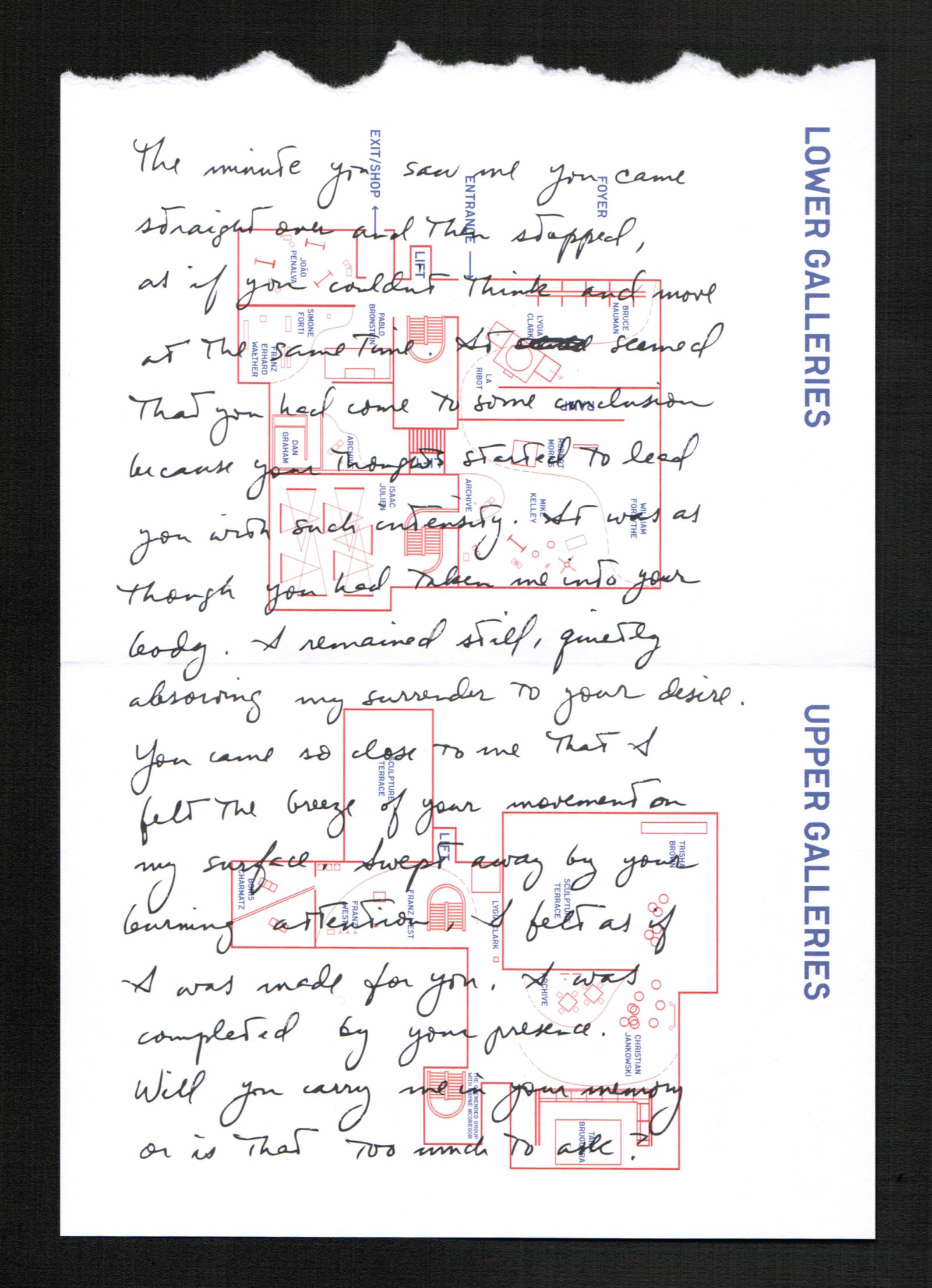

Well. As usual (as always?), I think we’re talking about ourselves. Maybe all criticism is about grief. The not matching. I wrote that on my friend José Carlos Teixeira’s wall at Headlands Center for the Arts in 2013, as part of a poem called “173–177 [or: Facebook Is Inescapable],” itself part of José’s project Translation(s), which grew and lived, for a time, in his studio at Headlands. At the end of our residencies, he painted over the poem and sent me the video footage (performance documentation) of its erasure (ephemerality). There is a way in which the translator must love failure / The thin line of light splitting the morning sky.

We’re all oppressed by our things, those of us who have enough things not to be oppressed by our lack of things. We make it so hard on ourselves. Another artist friend sent me a letter outlining all the things that a museum has to do before it can destroy an installation. I was exhausted just reading it.

But now, you see, I am in danger of tipping over into a celebration of ephemerality. To not leave a trace: such a political act of resistance! No, sorry. That is not how I intend to spend my last bit of time with you here.

I will say: the business of museums collecting performance strikes me as a particularly twenty-first-century absurdity.

Let’s close with some Thomas Pynchon: “Next thing you knew, the haircut was done, a whisk-broom all over her back, and clouds of scented powder in the air. A palm out for a tip.”

For Further Reference

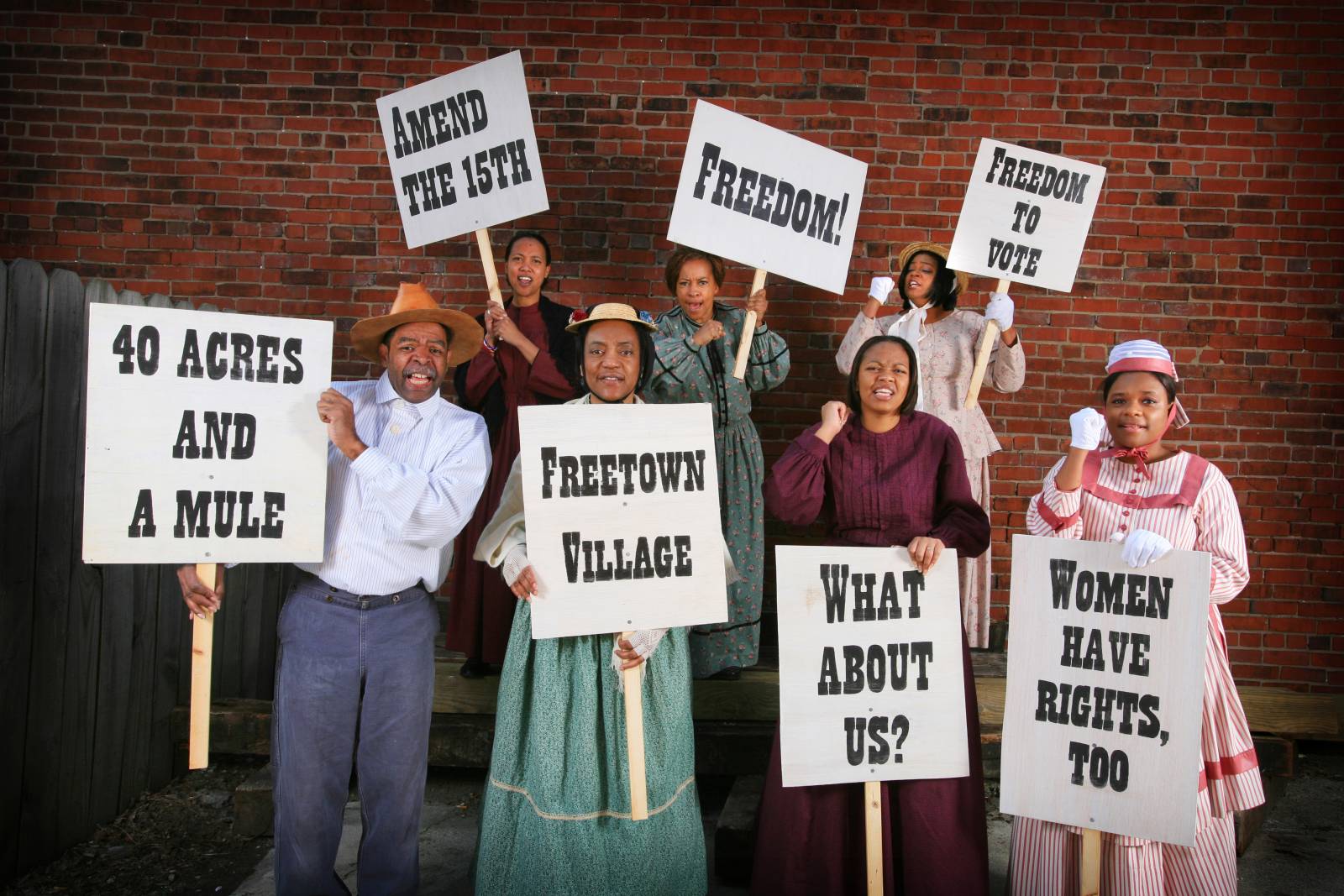

I was at first stymied by the prompt to list works associated with the terms duration and ephemerality . . . don’t virtually all performance works (all things?) possess duration and ephemerality? But then I started thinking of that old warhorse line, “You had to be there,” how it also relates to duration and ephemerality. You have to stick around while it’s happening because the work doesn’t stick around after it’s over—even (especially?) works that come back. And so here’s a list of works that for me exemplify this sort-of double entendre. (Including a poem I wrote: they asked us to include one of our works, and at first I couldn’t think what, since most of what I make exists on the page . . . but this one was a site-specific response, written on the wall of my friend José Carlos Teixeira’s studio as part of his Translation(s), a project developed at Headlands Center for the Arts and then painted over once our residencies were done). It takes the time it takes.

A Family of Perhaps Three, by Gertrude Stein. Target Margin Theater, 2009.

Elevator Repair Service, Gatz, 2006.

Sarah Michelson, Devotion, 2011.

Ralph Lemon, How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere?, 2010.

Justin Peck, In Creases, 2012.

Vicky Shick, Not Entirely Herself, 2011.

Jodi Melnick and David Neumann, July, 2011.

John Jesurun, Stopped Bridge of Dreams, 2012.

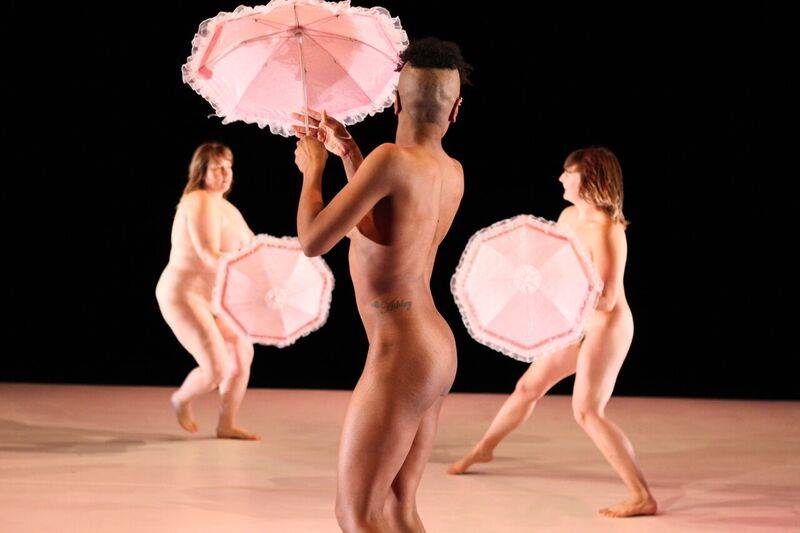

Trajal Harrell, Antigone Sr., 2012.

Radiohole and The Collapsable Giraffe, The Collapsable Hole, 2000–13.

The Merce Cunningham Dance Company, The Merce Cunningham Dance Company, 1953-2011.

“173-177 [or, Facebook Is Inescapable],” Claudia La Rocco, 2013.