Drunk Day (2010)

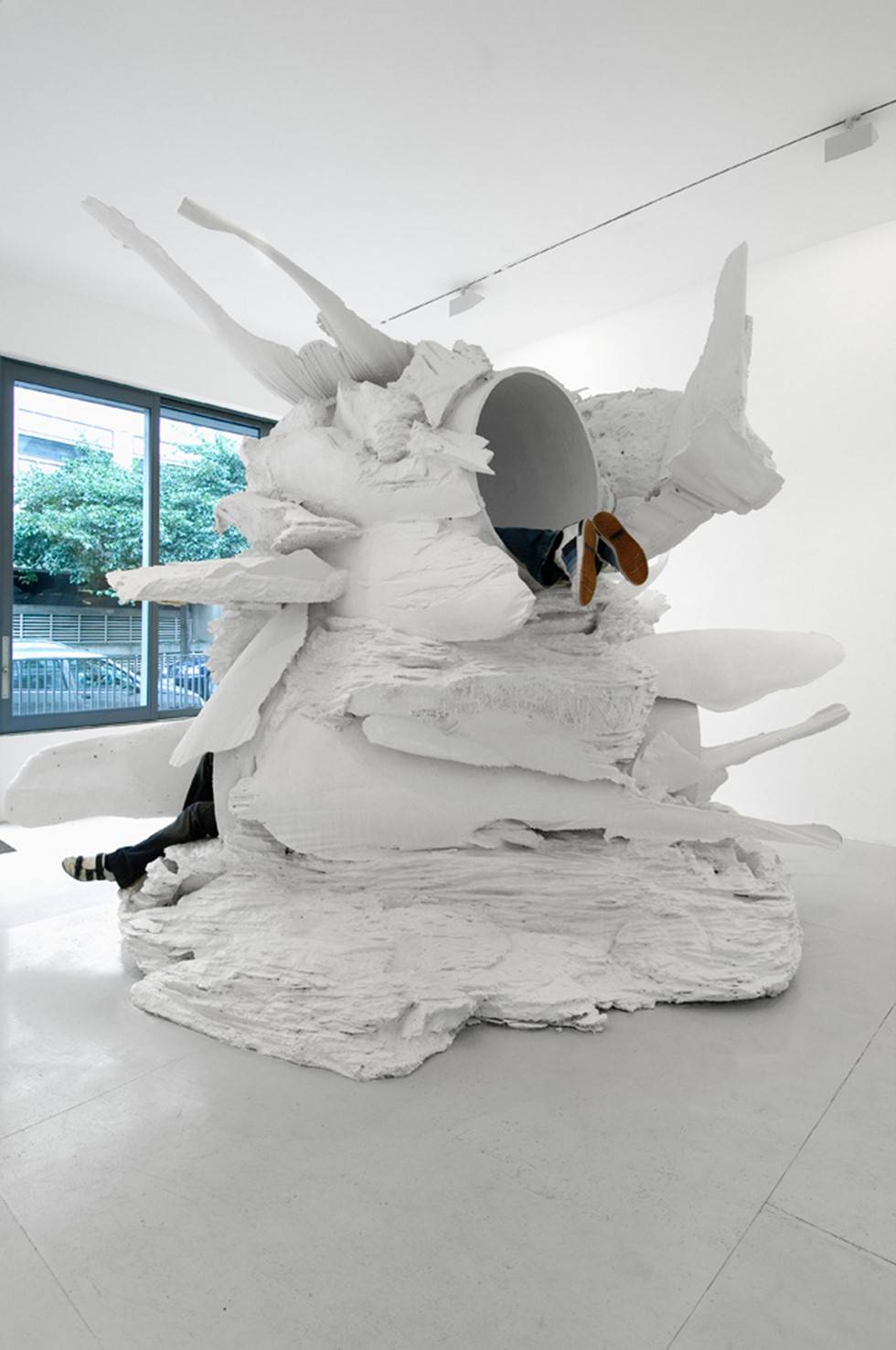

There is an exclusive ephemerality to the drunken dancing body. Intoxicated, the body-mind continuum is destabilized, and there is very little other conversation to be had. The continuum is no longer a mystery. It finds an inebriated equipoise, a stumbling body geography, balance.

Did I tell you that we had a “drunk day” in Lyon, France? A day organized near the end of my time making a dance for the Lyon Opera Ballet, to premiere at the Opéra National de Lyon. A day devoted to the dancers getting drunk and stoned. Something we had talked about doing from the very beginning of my research there.

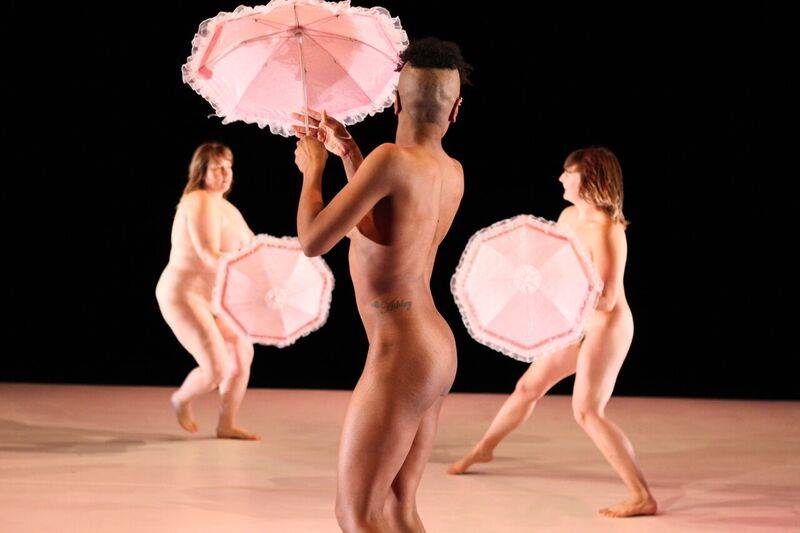

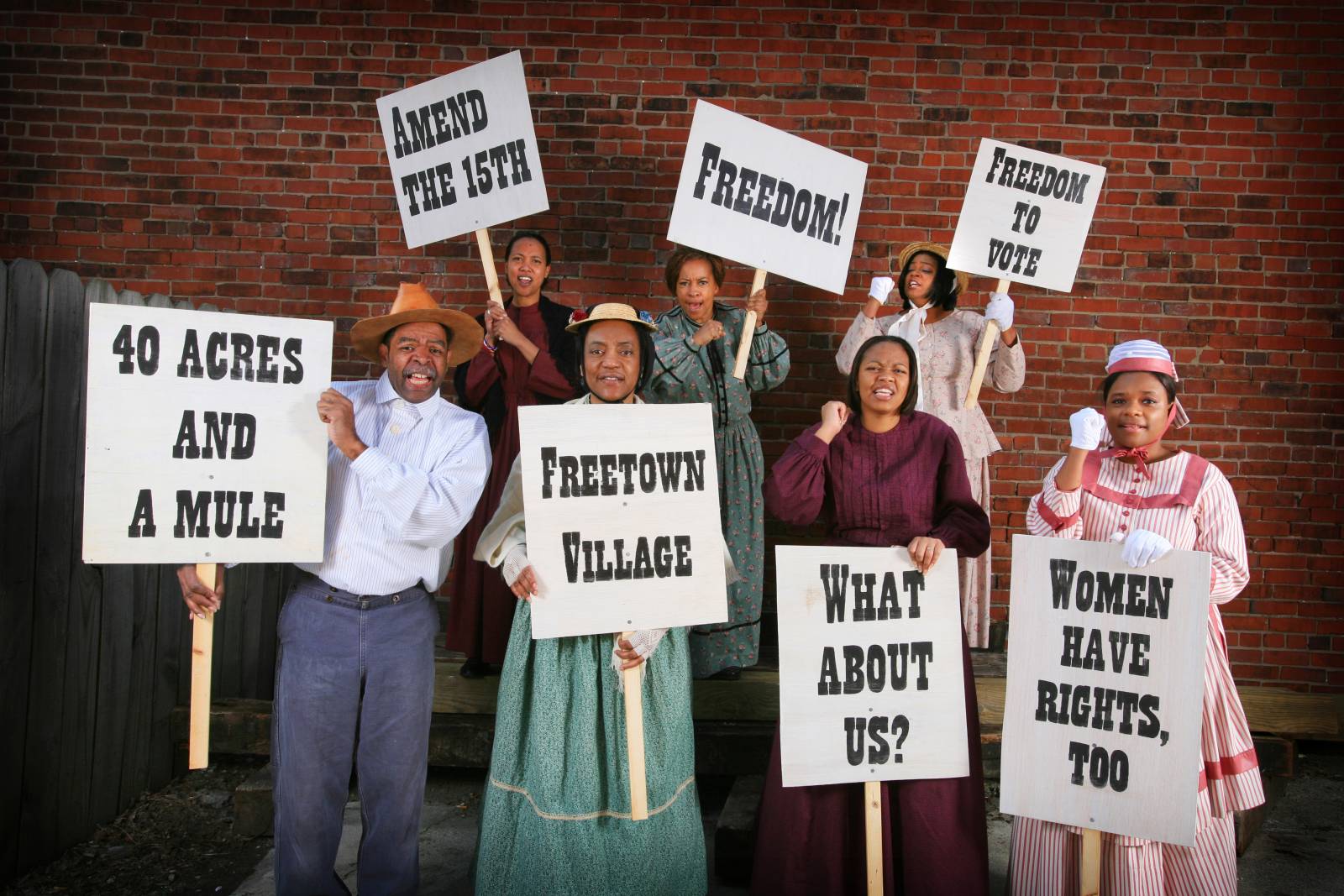

The Lyon drunk day turned out similar to the drunk day we held at BAM, in Brooklyn, with my all-black American team of dancers. Similar in that I’m not sure how useful it ultimately was. My American team, after a whole (ritualized) day of drinking, eating, smoking, and dancing, became an unmovable pile on the floor. Unmovable pleasure. Nothing much to behold other than the body joyfully watching itself collapse. An ultimate freedom, undanceable. What’s to watch? Although watching the many hours of them attempting to dance something comprehensible was exciting, for a while.

A French version this time, with a primarily white European dancing body politic. Once again, I hoped to incorporate some of the “out of control” material into the stage performance, to find some formal “sober” translation of their excess. But in Lyon it became more than just a sober dance vs. drunk dance turned into house party experiment, as it had been in Brooklyn. Something else happened. I suspect it was in part due to the youth of the bunch (becoming truly Dionysian?). That and their ballet training, with its severe daily practice. And their collective (keenly modern European) performance intelligence, born of the fact that they practically live on stage, in an opera house. What happened was no longer a mystery but became a Deleuzian delirium, perhaps. A simulation of some other kind of dance, or lie, or discovery.

Here are my notes:

After a few hours of work in the rehearsal space, we walked to a Casino (a French deli) and picked up bread and cheese and fruit (Alexis bought jelly beans), some pizza. A bottle of rum, a bottle of vodka, and 3 pints of fruit juice. Lots of water. We went to Aurelie’s apt., near the casino, near a park, and consumed and laughed. They didn’t drink (very) much, but enough. Smoked some pot, which David provided, smuggled from Brooklyn. Everyone was nicely loose. Francesca was crying, “This is my first time doing this. . . .” Most of them had never been stoned before.

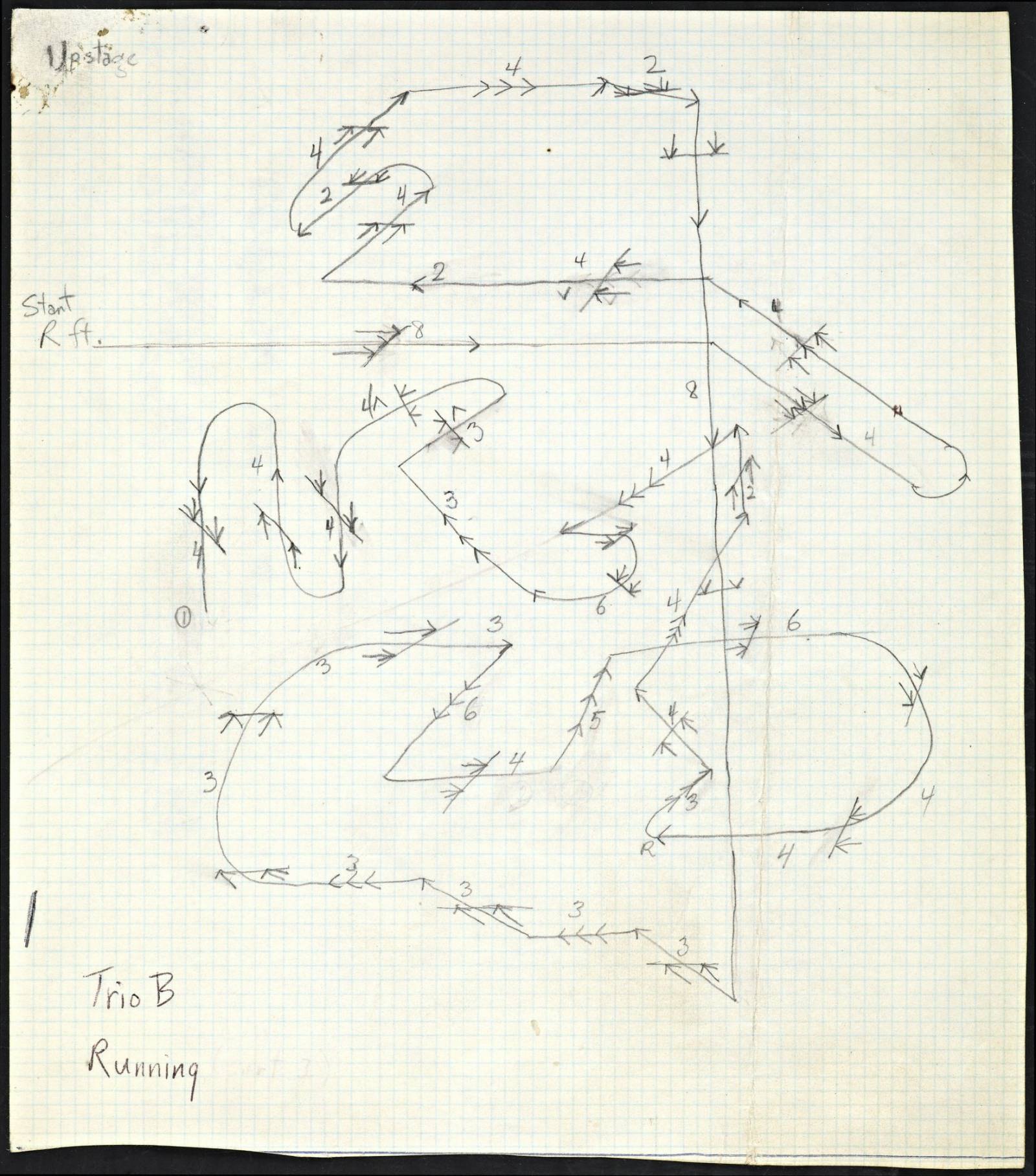

We walked to Park Tête d’Or, the largest park in Lyon. It reminds me of the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris, but with a zoo: monkeys, elephants, giraffes. We found a quiet and empty open field. Aurelie laid out three large blankets under a modest row of trees. We sat and I offered them a few dance projects: 1. Dance something impossible. 2. Something about being rescued, rescuing. 3. Something efficient and beautiful. What do you mean by beautiful? That the body should be joyful.

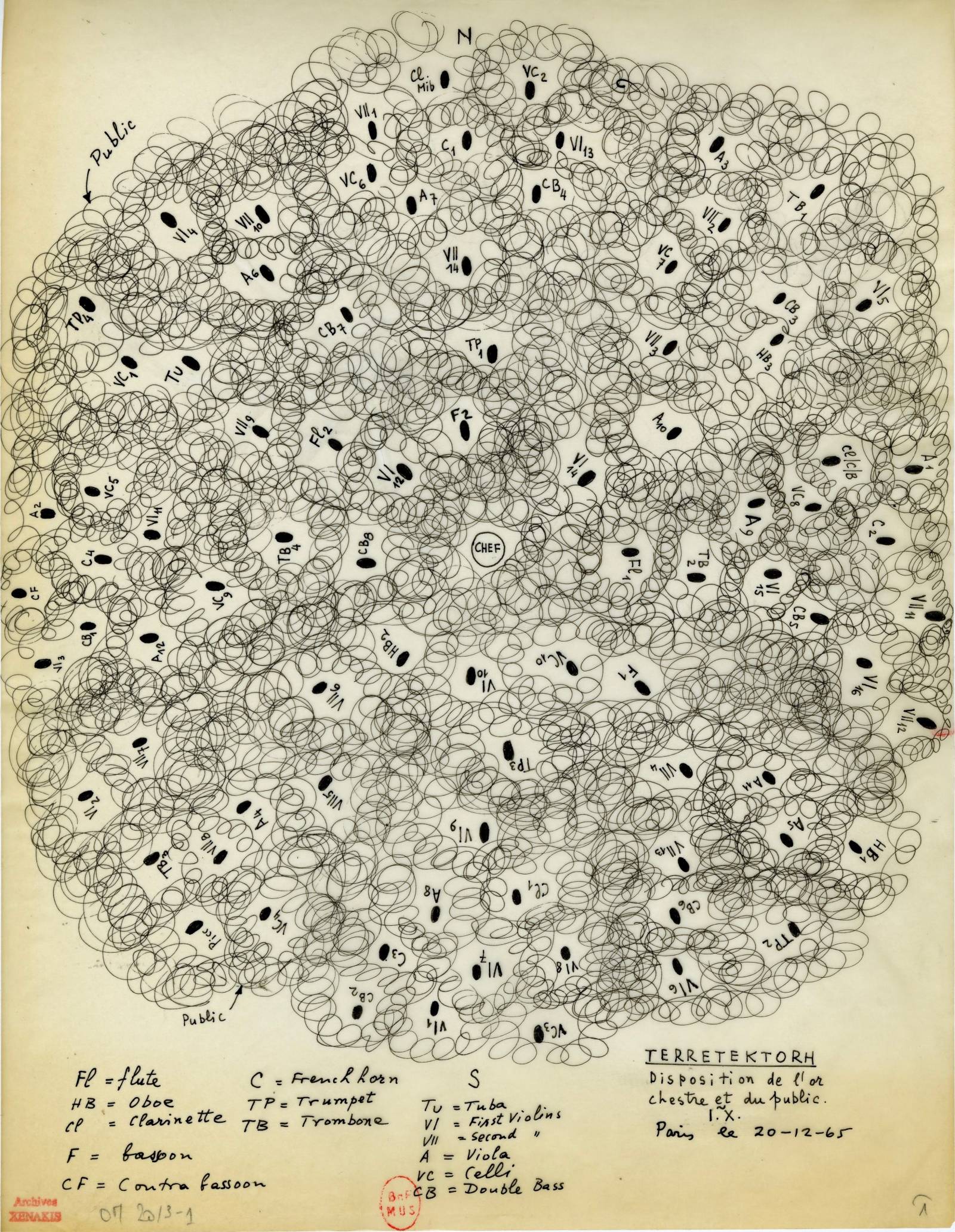

What I recall, what stuck out: Benoît attempting a series of pirouettes, over and over, without verticality, a leaning, falling furious centrifugal spinning (or maybe it was centripetal?). Eneka and Harris partnering as though there was nothing but the gravity of the grass, an inelegant physical contact with no form, and no gender dynamic, dull and committed. Almandine, so smart so strong, practiced stillness, a standing on one leg for a long time, that only shimmered in place, ultimately barely stable. Alexis and Aurelie ran around in a giant circle, the circumference of the entire park, laughing and transcribing some arrhythmic and broken petit allegro. Three-fourths of the way Alexis fell, becoming a skidding rolling bundle of outstretched limbs. Aurelie left him behind. Francesa, the most electrifying, found some real danger, a trance, a prone in-place dancing that just shook, violently, in one spot, digging herself into the dirt-packed ground not far from the pen of giraffes.

I videotaped everything. This extreme collective effervescence, getting lost, a new play.

At the end Eneka asked me to dance. Et vous, Ralph? Yes, I am a little high. And I did, throwing my body around impossibly, in the soft demanding grass, and discovered that there I didn’t want to dance, I wanted to sleep, in the soft grass cushion. So I did, for a few seconds. . . . David too joined the field, seductive, with a practiced uncertain beauty. Brooklyn, Park Tête d’Or, dancing like he dances every day, I thought. Someone else videotaped us.

At the end they were in awe. “What a day!” “I feel like it was a dream. . . .” “I have never done anything like this.” Well, of course, I said.

I told them that their bodies would remember this day, that was all. (They all begged for personal copies of the day’s documentation. I can’t recall if they ever received them. I’m not even sure where the MiniDv tape is now. My recollection of the day completely memorized.)

When I left a few were still there, under the trees, moving around, wide-eyed, lyrically stumbling. A vocabulary broken. Pleasure grasping at its own dissolve. This is dangerous work. (Legally, they are not allowed to leave the opera house when they are scheduled to rehearse.)

I walked home feeling close to ecstatic, not dangerous. The body is such a miraculous puzzle, and I am so grateful that I get to play a few of its many games.

I thought of this Allen Ginsberg quote:

Well, while I'm here I'll

do the work—

and what’s the Work?

To ease the pain of living.

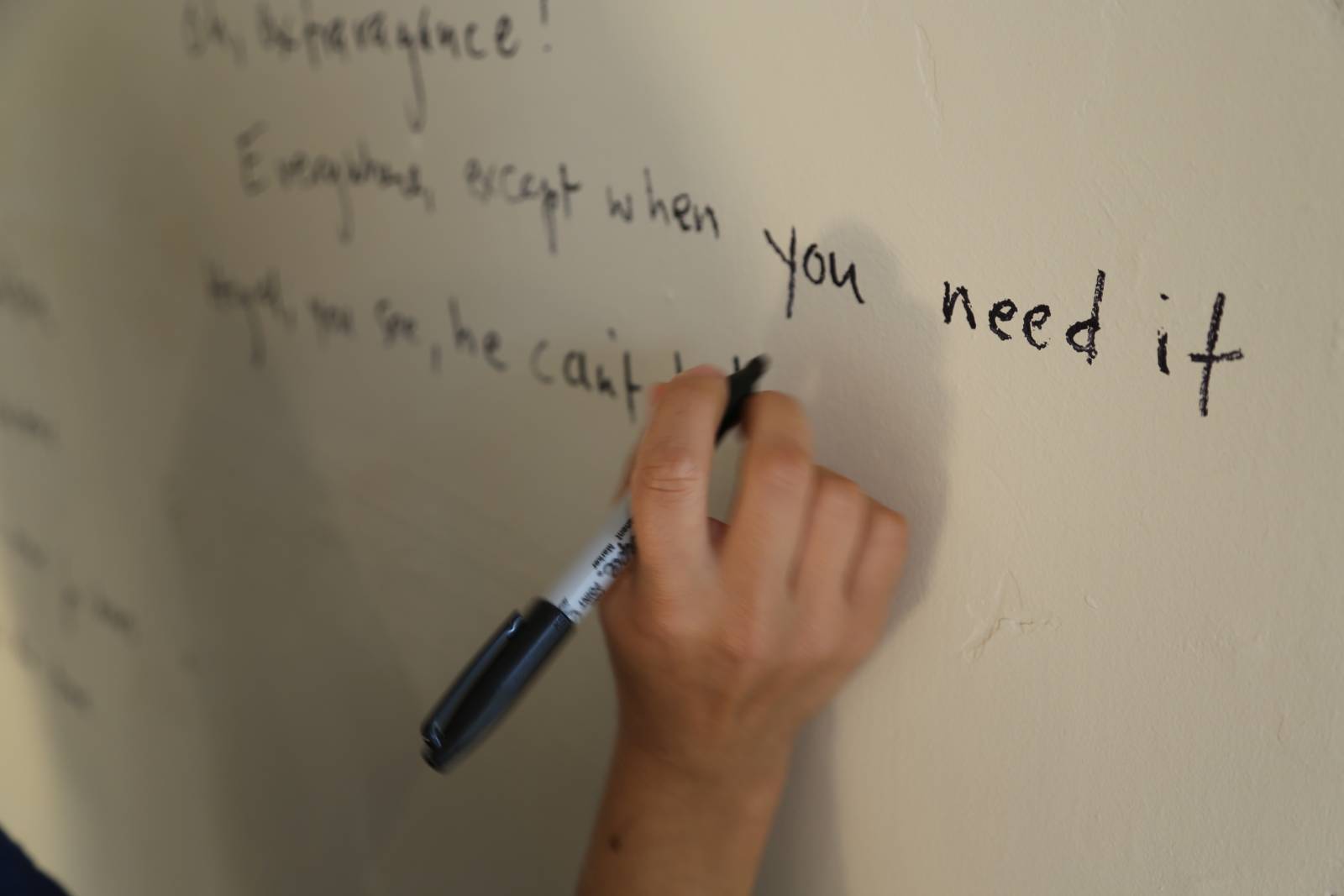

Everything else, drunken

dumbshow.

(“Memory Gardens,” Oct. 22–29, 1969)